Thanks to Jaci McKinnon for first making me aware of this interesting and little-known aspect of Coffee County’s history. In his History of Coffee County (1930), Warren P. Ward notes that Mormon missionaries came to the area in 1898, led first by Elder Nephi Henderson and an Elder Brewer. Elder Ben E. Rich established the church in Coffee County. He was succeeded by Elder Charles A. Callis. Early families who converted to the Mormon faith were those of Calvin W. Williams, Dan P. Lott, and Joseph J. Adams. “Many citizens of the county were excited over the appearance of the Elders. Some regarded them as messengers from Heaven, gave them shelter and lodging…Others regarded them as emissaries of the devil, wrecking homes and carrying away women…Coffee County has been a fruitful field for the Mormon Church, it having grown to a membership of over seven hundred. There are two churches in the territory-Cumorrah Church in Coffee County and the Utah Church in Atkinson County, formerly Coffee.” I’m not sure what happened to the congregation but will continue to research it and will photograph the nearby Mormon Cemetery the next time I’m in the area. (Thanks are also due to Andrew P. Wood for pointing me to Ward’s history of the Mormons in Coffee County) For articles and comments and more history about this Cumorah church visit the website here: https://vanishingsouthgeorgia.com/2013/11/06/cumorah-church-1907-coffee-county/

On July 21, 1879, as Joseph Standing and missionary companion Rudger Clawson traveled from Whitfield County toward a church conference in Chattooga County, they encountered an armed mob of twelve men in Varnell, Georgia . Before murdering Joseph the mob said, “There is no law in Georgia for the Mormons.” None of the mob were ever convicted. President McKay dedicated the site in Georgia and named an MTC building in Provo after him.

Historic Rural Churches

THERE IS NO LAW IN GEORGIA FOR MORMONS

A R T I C L E A N D P H O T O G R A P H Y B Y R A N D A L L D A V I S

On July 21, 1879, twenty-four-year-old missionary Joseph Standing of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and companion Rudger Clawson were traveling from Whitfield County to a church conference in Floyd County, in northwest Georgia. A confrontation with a mob of twelve near Varnell resulted in Standing’s murder. In the years that followed, there would be more incidents of assault, bombing, arson and kidnapping perpetrated against Mormons across the state. The Mormon church’s origin and doctrine, and events that occurred prior to Standing’s death, shed light on the outbreaks of violence against members of the faith—and sometimes acts perpetrated by them. A comprehensive history of the Mormon faith isn’t possible in an article of this length, but several events in Georgia and elsewhere, and the stories of two churches in South Georgia, are illustrative of the church’s growth and how sometimes it was perceived as a threat to the established social and ecclesiastical order.

Lawrence Wright’s 2002 article “Lives of the Saints” in The New Yorker magazine provided background information about the Mormon faith and is quoted generously for background purposes, along with the writings of Sally Denton, Wallace Stengner and Gilbert Smith. The Mormon faith originated in 1820 in Manchester, New York, when, “a fourteen-year-old named Joseph Smith had a visitation.” Wright explained that “[it] was a fertile and turbulent time in American religious history. Old beliefs were losing their influence, and new ones were arising that were more responsive to America’s revivalist spirit. The upstate region where Smith was living was known as the ‘burnt-over district,’ because of the religious fevers that continually swept through it. One morning, Smith, who was trying to sort out the claims of truth that each denomination put forward, went into the woods to pray for guidance. He had no sooner knelt than he

sensed the presence of a higher power and felt himself surrounded by darkness. ‘Just at this moment of great alarm, I saw a pillar of light exactly over my head, above the brightness ot he Sun, which descended gradually until it fell upon me,’ Smith wrote in a brief memoir. The two ‘personages’ hovering in the air took form and Smith took them to be God and Jesus.

Smith found the composure to ask which sect was right.” Wright recounted the message the angels gave Smith about other denominations: “I was answered that I must join none of them, for they were all wrong; and the personage who addressed me said that ‘all their creeds were an abomination in his sight.’” In a moment everything returned to normal and

later Smith told his mother, “‘I have learned for myself that Presbyterianism is not true.’”

“Three years later (1823),” Wright continued, “Smith had another visitation, this one from an angel named Moroni, who revealed to him that an ancient book written on golden plates was buried nearby on a hill called Cumorah.” In 1827 Smith “returned to Cumorah and again encountered Moroni. This

time, the angel entrusted the golden plates to him, along with a pair of ‘seeing stones,’ called the Urim and Thummim, which permitted him to translate the strange language inscribed on the plates (identified by Smith as ‘reformed Egyptian’).” Three years later, Smith published the Book of Mormon. “It was prefaced by the statements of eleven witnesses who claimed to have seen the golden plates and, in eight cases, to have actually

‘hefted’ them. The plates themselves, however, were no longer available for examination. With the ‘translation’ finished, Moroni had reclaimed them and taken them back to Heaven.”

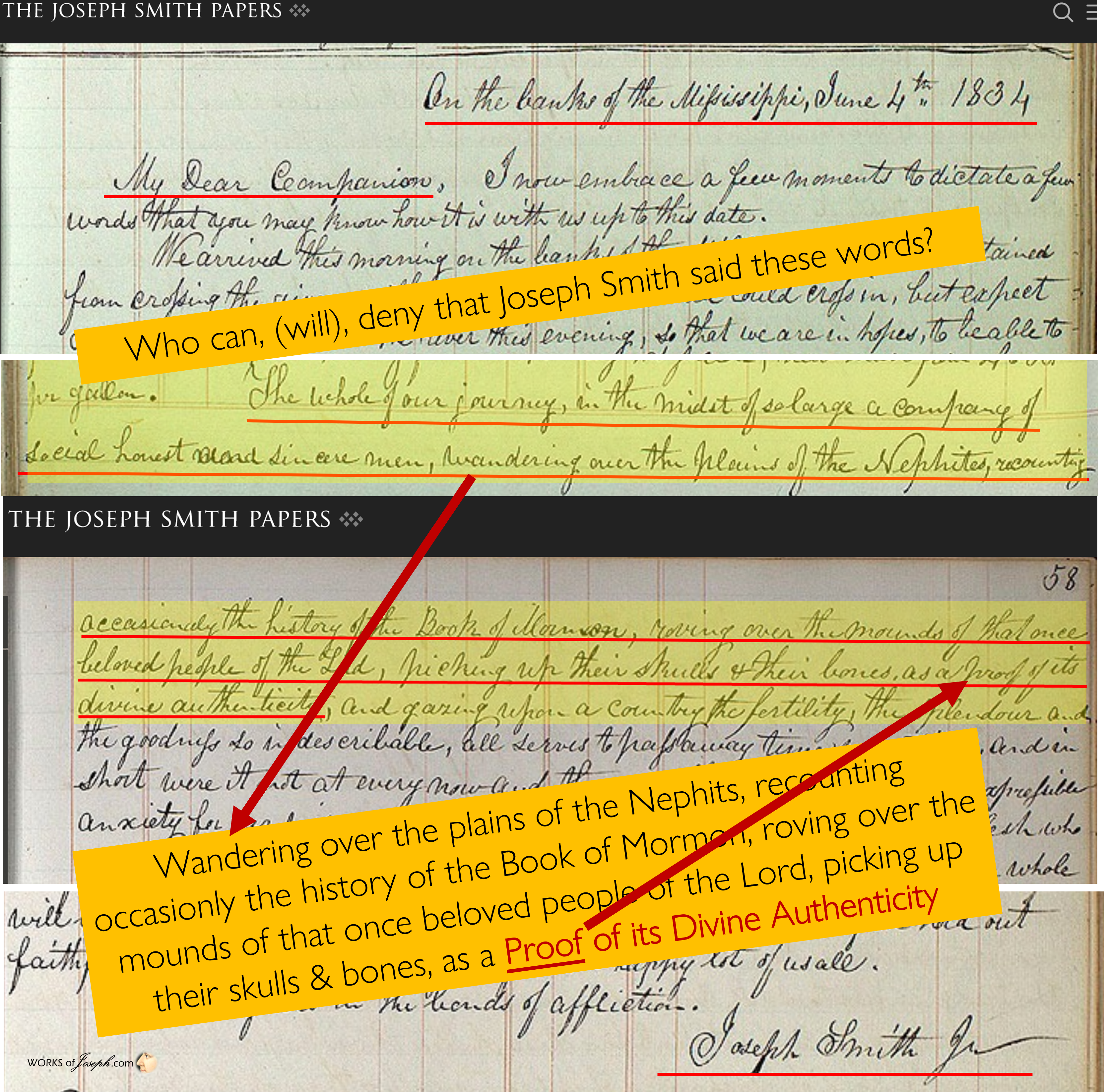

The Mormon faith originated in a conflict set in the New World. According to Wright, “The Book of Mormon purports to be the history of two tribes of Israel—the fair-skinned, virtuous Nephites and the dark-skinned, conniving Lamanites, The Nephites and the Lamanites battled for centuries, eventually carrying their feud into North America. In the midst of their warfare, the resurrected Jesus suddenly appears in the New World, demanding repentance… The two tribes are temporarily reconciled. But, four hundred years later, the Nephite leader Mormon is slain, with hundreds of thousands of his people, in the final triumph of the Lamanites. Mormon’s son, Moroni, survives to record this last event on the golden plates, which are then buried on [a hill named] Cumorah.”

Joseph Smith was a down-to-earth, unrefined farmer with no formal education but possessed of an engaging, charismatic personality. In 19th century rural America, religious fervor was high, and many tended to reject the ritual of older, more established denominations in favor of newer and more evangelical ones, like the Baptists and Methodists. In this environment, the idea of a new, homegrown faith that posited the divinity of the individual, allowed direct communication with God, and recognized

the authority of the Bible, took hold. The Book of Mormon and its visionary young prophet attracted a surprising number of converts and followers.

Along with this success came criticism. Wright wrote that, “By the time he was in his mid-twenties Smith had become one of the most controversial men in America. …From the beginning, it was a missionary creed, and Smith sent emissaries throughout America and abroad. Thousands of followers were drawn to his ministry, including Brigham Young, a young carpenter in upstate New York, who became one of the greatest colonizers of the West. The Mormons, at first derided as cranks, were soon objects of fear and hatred, not just because of their heretical beliefs but also because of their communal economy, their monolithic politics, and, eventually, their practice of polygamy.”

The unusual doctrine and practices by leaders and members of the church drew the scrutiny and ire of those committed to more traditional beliefs. In the nine years that remained in Smith’s brief life, his disciples “were driven from one settlement after another, in what was an unparalleled assault of religious persecution in America.”

The persecution endured by Smith’s followers was extensive.The Mormons were driven from towns in New York to Kirtland, Ohio, and then to Independence, Missouri, where yet again their presence angered residents. Vigilantes burned homes, and Smith was beaten, tarred and feathered, and an attempt was made to force him to drink poison. The governor of Missouri ordered the state militia to subdue the Mormon population and to arrest Smith and other leaders.

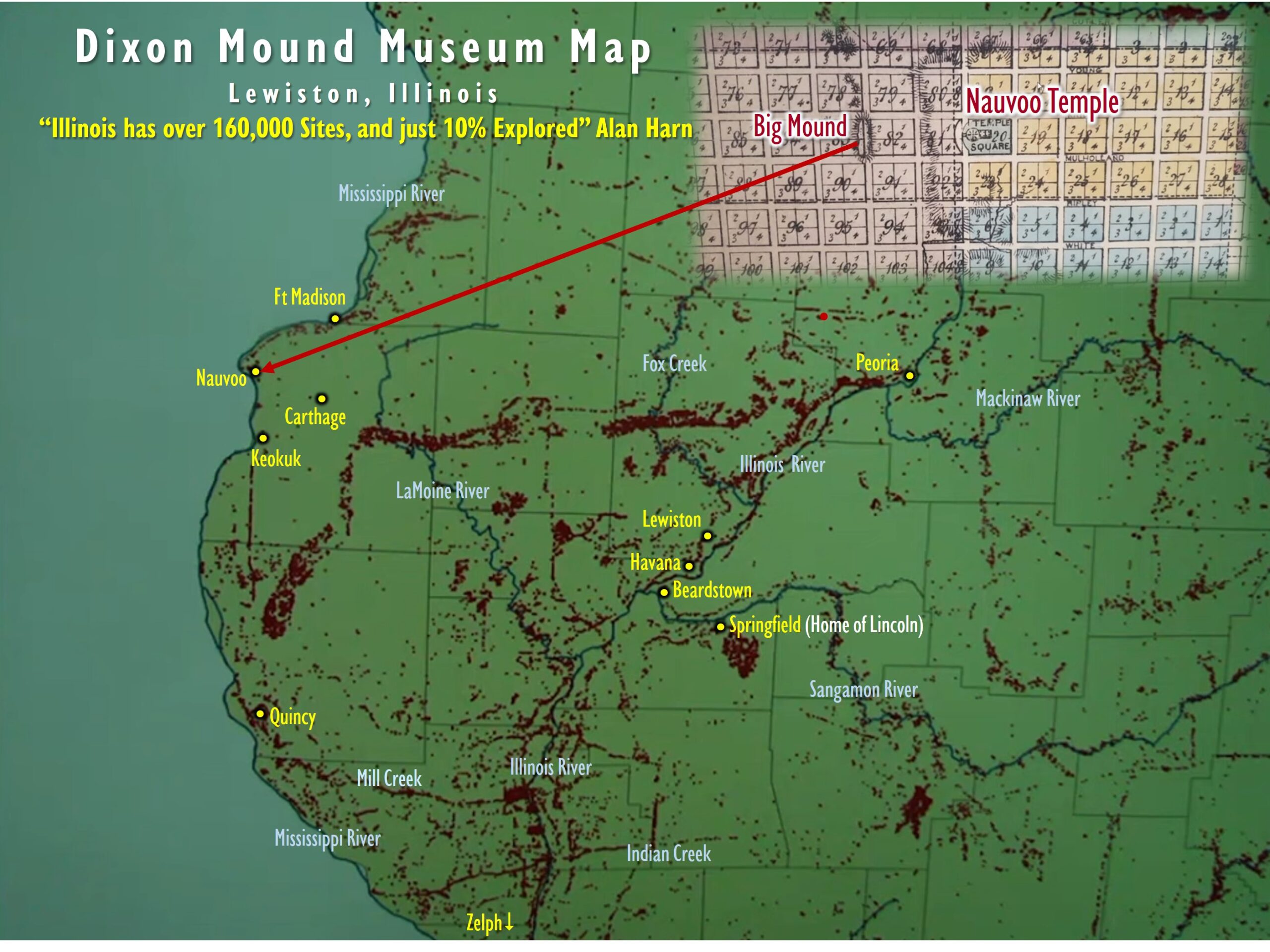

Meanwhile Brigham Young fled the area, with a core of believers, to Quincy, Illinois. When Smith and his associates escaped captivity, he bought land on the Mississippi River, where he established the town of Nauvoo, Illinois. It was there that the idea of a “plurality of wives” developed, triggering even more antagonism. Facing accusations of philandering, he received a revelation that allowed any man to take as many consenting wives as he deemed necessary. Eventually, he would take a reported 40, most in the last

years of his life, including a 14-year-old girl and the wives of other members of the church. With a warrant out for his arrest, Smith surrendered to authorities at the non-Mormon town of Carthage.

While in custody, he and his brother Hyrum were shot to death by a mob in 1844. Smith uttered his last words—”Oh, Lord, my God”—and fell from a second-story window to the street. There he was propped against a well and shot again by a four-man firing squad. Wallace Stegner, a widely published novelist and historian who admired the LDS, once described early Mormons in Utah as “a sociological island of fanatic believers dedicated to a creed that the rest of America thought either vicious or mad.” In his study of diaries and letters of Mormons in the West, Stegner came to respect their “suffering, endurance, discipline, faith, brotherly and sisterly charity.” Balancing these, he also noted their “human cussedness, vengefulness, masochism, backbiting, violence, ignorance, selfishness and gullibility.”

Pushed further and further west, the Mormons arrived in Utah in 1847. Ten years later, they became embroiled in conflict with the United States government. Federal troops received orders to “unseat Brigham Young,” the territory’s governor. “Young declared martial law and prepared his followers to burn down their homes and retreat to the mountains for

guerrilla warfare.”

Under constant persecution, Mormons became a selfreliant and fiercely independent people. Their expulsion by the State of Missouri, during which prominent Mormon apostle David W. Patten was killed in battle, the murders of Joseph and Hyrum Smith, and the unceasing antagonism from those outside the faith undoubtedly encouraged Mormons to view

most who didn’t share their faith with suspicion and sometimes outright hostility.

Suspicion turned into hostility in 1857, when a wagon train of thirty well-to-do non-Mormon families, most from Arkansas, entered Utah en route to California. “The Mormons viewed the newcomers with hostility,” Wright noted, “partly because of the recent news that one of the Church’s apostles,

Parley Pratt, had been murdered in Arkansas.” When the wagon train reached Mountain Meadows in southwestern Utah it was attacked by armed Mormons, resulting in the death of 120, including many women and infants. The Mormon Church quickly blamed a few renegade church members for the massacre and said that Paiute Indians had killed the women and children. But in 1999, bones uncovered at the site showed signs that the women and children had been shot at close range.

Mark Twain accused Brigham Young of ordering the Mountain Meadow killings. The jailhouse confession of John D. Lee, an adopted son of Young’s who was executed by the government for his part in the massacre, told one version of what happened. Lee claimed that a band of Paiutes numbering

300 to 400 led the attack that continued for four days. Lee claimed that he, under a flag of truce, approached the wagon train to present terms of surrender. The battle-weary emigrants, with seven dead and sixteen wounded, put down their weapons in exchange for a promise of safe passage. Then, at a pre-arranged signal, the Mormon militia shot them all, leaving the women and children to fall under the clubs, knives and

hatchets of the Paiutes. Seventeen of the youngest children were spared.

“Twain believed that the ‘Indians’ involved were actually Mormons wearing war paint, which conforms to accounts given by surviving children,” Wright wrote. Lee, the only person involved in the incident who was convicted, was executed by firing squad at Mountain Meadows.

As Wright explained, “News of the massacre prompted members of Congress to call for the elimination of the Church.” Brigham Young forestalled a federal investigation into the massacre by stepping down as the territorial governor.

At a memorial ceremony on September 11, 2007, the sesquicentennial of the Mountain Meadows massacre, LDS Apostle Henry B. Eyring read the church’s official statement to gatherers: “We express profound regret for the massacre carried out in this valley 150 years ago today, and for the undue and untold suffering experienced by the victims then and by their

relatives to the present time. A separate expression of regret is owed the Paiute people who have unjustly borne for too long the principal blame for what occurred during the massacre. Although the extent of their involvement is disputed, it is believed they would not have participated without the direction and stimulus provided by local church leaders and members.”

The Mountain Meadows Massacre deepened dislike of the Mormon Church, perceived as a lawless and rebellious sect with heretical beliefs. This helped set the stage for incidents to come. Wright observed that, “In addition to this troubled legacy the practice of polygamy proved to be a bigger burden,

which kept alive the hostility of Victorian America toward the sect.” Plural marriage, as it came to be called, was contrary to the Book of Mormon. Indeed, monogamy was the official doctrine of the Church throughout Smith’s life.

After Smith’s death, the doctrine of plural marriage became settled. Wright is quoted again: “In 1866, Brigham Young declared, ‘The only men who become gods, even the sons of God, are those who enter into polygamy.’ He set an example by marrying perhaps fifty-five women. Throughout the 19th

century, it was popularly assumed that Mormon women were little more than sex slaves, even though they sometimes pointed out that they had chosen polygamous unions.” Young also encouraged women to take up the professions of law and medicine, and, as governor, allowed them to vote, long before women elsewhere in the United States enjoyed such privileges.

In 1862, Congress passed the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act, but President Abraham Lincoln elected not to enforce the law. Instead, he gave Brigham Young tacit permission to ignore it. In return, Young kept the Utah Territory from becoming involved in the Civil War.

Persecution and prosecution of Mormons continued, as attested by the arrest of more than a thousand on polygamy related offenses. To avoid oppression many Mormons fled to Canada and Mexico. Wright noted that, “In 1890, the United States Supreme Court sanctioned the nationwide confiscation of virtually all Mormon property, essentially authorizing that the movement be crushed.”

That same year, LDS president Wilford Woodruff received a revelation that inspired him to declare, in what is called the 1890 Manifesto, that plural marriage was no longer officially allowed.” But this did little to erase hostility towards the Mormon faith. The disapproval non-believers felt for the faith was apparent in an April 25, 1901, article in the Vienna [Ga.] Progress: “The Mormon doctrine sprang from one Joseph Smith who evidently had an awful dream from an overload of supper. The elders, while here, were treated kindly, and no eggs were given them, except at the hotel.”

A 1906 newspaper article reported that the number of converts to the Mormon Church over the prior decade exceeded by several thousand the number of converts to the Methodist, Baptist and Congregational churches combined. When those numbers were translated into votes, politicians nationwide took notice. Vitriol-filled anti-Mormon newspaper articles

appeared, often quoting statements from the non-Mormon pulpit. For instance, Dr. John White of Atlanta’s Second Baptist Church proclaimed that Mormon propaganda was “false, evil and dangerous and should be shunned like a viper.” Political and religious opposition to LDS doctrine and practices continued and helped shape and perpetrate anti-Mormon

sentiment.

In 1878 the headquarters of the newly established LDS Southern States Mission moved from Nashville, Tennessee, to Rome, Georgia. The church enjoyed notable success in northwest Georgia, especially in Chattooga County’s Haywood Valley. But local newspaper editors, ministers, and the Ku Klux Klan, all of whom decried Mormon practices of polygamy and conversion by baptism, opposed the movement. It was the next year that a mob murdered missionary Joseph Standing in Whitfield County. Standing’s traveling companion, Rudger Clawson, witnessed the incident and reported that Standing had pulled a gun on the mob in self defense.

The mob responded by riddling him with more than 20 bullets. Of those brought to trial, all were acquitted. Standing became a martyr and was laid to rest in Salt Lake City, Utah, where the Latter-day Saints erected a monument bearing the words: “There is no law in Georgia for the Mormons.” Today a small park in Varnell includes a marker with a bronze plaque to mark the spot where Standing was gunned down.

Standing’s murder seemed to spur opposition to Mormon missionaries throughout north Georgia. Missionaries were beaten, pulled from their beds, kidnapped, wounded, and denied the right to preach (or were egged when they did). In a retreat to Tennessee, Mission headquarters was moved from Rome to Chattanooga. Limited for several years, missionary work in the region finally resumed in earnest in the 1890s. Gradually, the Mormon faith spread into other parts of Georgia. By the early 20th century, there was a congregation in Douglas (Coffee County), Montreal (DeKalb County) and Buchanan (Haralson County). As in the past, some of these faced hostility. For instance, somebody used 50 pounds of dynamite to destroy the rented building occupied by the Mormon Church in Montreal in 1908. According to the Atlanta Constitution, the explosion was heard ten to fifteen miles away. The building’s owner, who wasn’t a Mormon, said that he “was thoroughly aroused as to the seriousness of the situation” and feared future attacks might destroy his home or take his life.

Four years later, fire destroyed the Mormon Church in Buchanan while the congregation attended a nearby religious debate. The building, only a year old, was believed to have been destroyed by “an incendiary device,” but no arrests were made. A new stone church was completed after a pitched battle with opponents.

A Thomasville newspaper article in July 1899 related the story of three Mormon missionaries preaching their doctrine near Covington. While seated on the porch of “the Cunnard house,” a mob of masked attackers brandishing guns showed up. Cunnard went inside and retrieved his shotgun, presumably for defense of family and self. The light illuminating the porch was extinguished and pistol shots rang out followed by

a shotgun blast. The mob withdrew, taking the missionaries with them. When light was restored it was discovered that Mrs. Cunnard lay dead from a shotgun blast to the face. There was speculation that the missionaries were lynched but a later article stated they had escaped.

Only two rural LDS churches were established in South Georgia, both in Coffee County. Mormon missionaries there met with some resistance while other non-Mormons demonstrated a tolerance that developed into theological union. In recruiting for new members, the missionaries sometimes set up shop at a public place, such as the local post office, where

members of the public were sure to come.

This diary excerpt from Mormon missionary Adam Brewer relates an example of how these missionaries were treated: The day was spent in Pearson (Atkinson County today, bu part of Coffee County at the time) at the post office. We met some who were very bitter to the cause of truth and my companions talked to them at some length explaining the scriptures to them. In the evening we held a meeting but very few came out to hear us. We found in the teacher’s desk at the school house the following invitation.

‘Pearson a a , 8 23 1899 To Mormon Elders, If yew want to get out of this town with hole skin and bones and no tears on your physiagmany, don’t let the next sun set on you here.’

We don’t know what the significance of the two a’s following the town name of Pearson, perhaps it was meant to be g a (for Georgia) and are uncertain if the word tears was correctly read, but the intent is clear. Little Utah was one of two churches established by Mormons in Coffee County. A granite monument where the church once stood bears this inscription: “In the spring of 1899 the first Mormon missionaries came to Coffee County.

In 1905, two acres were deeded to the LDS Church for the building of a church and cemetery. A small church made of rough lumber was built and was used for church services and school until 1917. In 1918 a new church was built on the site and was known as Axson Ward LDS Chapel, Satilla Branch. Local non-members called it, derisively, ‘Little Utah’ because

missionaries from Utah baptized the first converts there. The members eventually embraced the name.”

Little Utah became inactive, possibly around 1975. The church building was sold and moved. Today the graveyard is still maintained. John Adams wrote a history of Cumorah Chapel, also in Little Utah church in 1953 (LEFT) and today (RIGHT) in a different location. Coffee County, in 1934. He recalled that in June 1899 his father, Joseph Adams, was visiting a brother-in-law when two Elders of the LDS Church arrived and began to preach the “restored gospel.” The next day the missionaries were to preach

at a Baptist church known as Old Mt. Zion, but upon arrival they were met by members bearing knives and guns who would not allow them to preach in the church. One member brought out benches from the church, placed them in the shade of some oak trees, and the missionaries were allowed to preach. The sermon must have been moving; thereafter, the missionaries canvassed the countryside. They received a fair share of rotten eggs but also began to find some “very staunch friends.”

Excessive rain in 1900 caused a catastrophic failure of crops in Coffee County. Many residents had to sell their farms; among them Joseph Adams and Uncle Dan Lott, who, along with their families, were LDS members. They both bought adjoining farms near Douglas and moved to their new homes in 1900 and 1901. While recovering from the catastrophic crop loss, LDS elders continued to work among the converts using the two farms as their base. The congregation increased over the next few years and a chapel was erected in 1907 on land given by Joseph Adams. Elder Tate named the new church building Cumorah. The first sermon was preached there in

August 1907. Use of the church building ceased around 1975. Despite decades of controversy and persecution in Georgia, the Latter-day Saints eventually came to thrive here. In 1916, the Southern States Mission moved to Atlanta. By 1936, there were more than 1,800 Mormons in the state. Today there are 84,500 members in 155 congregations. A temple, the most sacred of Mormon buildings, was dedicated in Sandy Springs in

1983, its spire topped by the golden figure of the angel Moroni. Randall Davis is a freelance writer and photographer in Statesboro.

See Additional blog with persecutions in Tennessee here: https://www.bofm.blog/tennessee-massacre/