Early Woodland period (1500 BC–200 BC) ADENA

Middle Woodland period (200 BC–500 AD) HOPEWELL

Late Woodland period (500–1000 AD) FORT ANCIENT

Mississippian Period (1000 -1500 AD) EARLY-LATE

JAREDITES (22OO BC – 586 BC)

NEPHITES (600 BC – 421 AD)

“The Hopewell Culture was contemporaneous with the end of the Adena culture, but the Adena people tended to be considerably larger than the Hopewell. Remains of men seven feet tall were common among the Adena, while Hopewell were robust, their males averaged closer to six feet in height. There are four types of earthworks that were constructed by the ancient Hopewell civilization.

“The Hopewell Culture was contemporaneous with the end of the Adena culture, but the Adena people tended to be considerably larger than the Hopewell. Remains of men seven feet tall were common among the Adena, while Hopewell were robust, their males averaged closer to six feet in height. There are four types of earthworks that were constructed by the ancient Hopewell civilization.

- Defensive Enclosure Mounds

- Burial Mounds

- Effigy (Shaped) Mounds

- Ceremonial and Temple Mounds

“Mounds were used chiefly as burial places but also as elevated foundations for special structures such as temples (Marietta, OH), hill top enclosures (Fort Ancient, OH), as totemic representations (Serpent Mound in Ohio), and ceremonial space and structures, (The great Circle/Octagon complex, Newark, OH). In size they vary from less than one acre in area to more than 100 acres. Over 200,000 earthworks dotted America’s Heartland.” The Book of Mormon in America’s Heartland by Rodney Meldrum

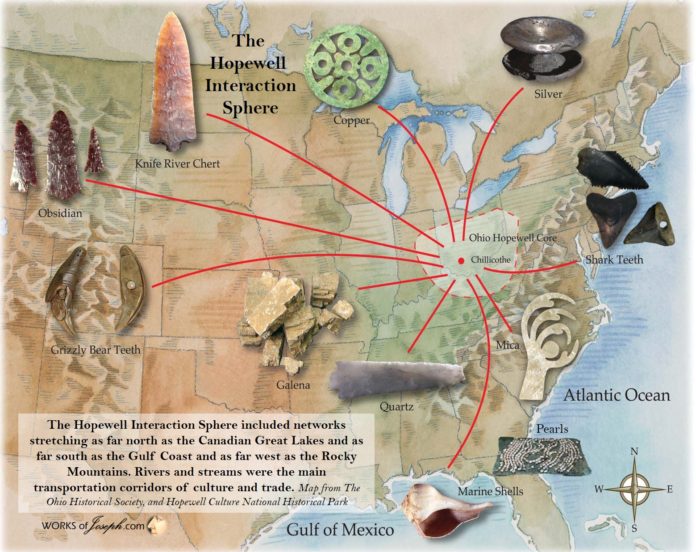

The Hopewell Culture describes the common aspects of the Native American culture that flourished along rivers in the northeastern and midwestern United States from 300 BC to 400 AD, in the Middle Woodland period. The Hopewell tradition was not a single culture or society, but a widely dispersed set of related populations. They were connected by a network of trade routes, known as the Hopewell Exchange System.

The Hopewell Culture describes the common aspects of the Native American culture that flourished along rivers in the northeastern and midwestern United States from 300 BC to 400 AD, in the Middle Woodland period. The Hopewell tradition was not a single culture or society, but a widely dispersed set of related populations. They were connected by a network of trade routes, known as the Hopewell Exchange System.- At its greatest extent, the Hopewell Exchange System ran from the Southeastern United States as far south as the Crystal River Indian Mounds into the southeastern Canadian shores of Lake Ontario up north. Within this area societies participated in a high degree of exchange with the highest amount of activity along waterways. The Hopewell Exchange System included copper from the Great Lakes, mica from the Carolinas, obsidian from the Rocky Mountains, and shells from the Gulf Coast. These people then converted the materials into products and exported them through local and regional exchange networks. Although the origins of the Hopewell are still under discussion, the Hopewell culture can also be considered a cultural climax, ending suddenly in about 400 AD.

- Hopewell populations originated in western New York and moved south into Ohio where they built on top of the local Adena mortuary tradition. Hopewell was also said to have originated in western Illinois and spread by diffusion … to southern Ohio. Similarly, the Havana Hopewell tradition was thought to have spread up the Illinois River and into southwestern Michigan, spawning Goodall Hopewell.

- The name “Hopewell” was applied by Warren K. Moorehead after his explorations of the Hopewell Mound Group in Ross County, Ohio in 1891 and 1892. The mound group itself was named for the family that owned the earthworks at the time.

- The Hopewell location in the Mississippi Valley, plains of Illinois, and Indiana and locations in Ohio match up with the location of the Nephites in the Book of Mormon. The time period also shows a great correlation, especially as both the Hopewell and Nephite civilization abruptly ended in about 400 AD.” The Book of Mormon in America’s Heartland page 102 by Rodney Meldrum

Parallels of the Hopewell Culture

Parallels of the Hopewell Culture as described by William C. Mills, Chief Archaeologist of Ohio, with the Book of Mormon“[May 20, 1917; Sunday] Attended Sunday School and afternoon service in Hawthorne Hall, and was a speaker at each assembly. Evening meetings here, as also in Brooklyn, have been discontinued for the summer. The attendance both at Sunday School and afternoon meeting was surprisingly large in view of the fact that many of the Utah college students have left for the vacation period. This evening at the hotel I had a long and profitable consultation with Professor Wm. C. Mills, State Archaeologist of Ohio. He is continuing his splendid work of exploration in the Ohio mounds, and I went over with him again the remarkable agreement between his deductions and the Book of Mormon story. He has reached the following (10) conclusions: The area now included within the political boundaries defining the State of Ohio was once inhabited by two distinct peoples, representing two cultures, a higher and a lower. These two classes were contemporaries; in other words, the higher and the lower culture represented distinct phases of development existing at one time and in contiguous sections, and furnish in no sense an instance of evolution by which the lower culture was developed into the higher. These two cultural types or distinct peoples were generally in a state of hostility one toward the other, the lower culture being more commonly the aggressor and the higher the defender. During limited periods, however, the two types, classes, or cultures, lived in a state of neutrality, amounting in fact to friendly intercourse. The numerous exhumations of human bones demonstrate that the people of the lower type, if not indeed both cultures, were very generally affected by syphilis, indicating a prevalent condition of lasciviousness. Their (are) two peoples or cultures…the lower culture was most commonly the assailing party, while the people of the higher type defended as best they could but in general fled. As a further consequence of this belligerent status they buried their dead, with or without previous cremation, in such condition as to admit of expeditious covering up of the cemeteries by the heaping of earth over the sepulchers [sic], in which hurried work the least skilled laborers and even children could be employed. From a careful collating of data it is demonstrated that the general course of migration through the area now defined as the State of Ohio was inward from the west and outward toward the east. Professor Mills states that no definite data as to the age of these peoples have as yet been found, but that the mounds may date back a few hundred years or even fifteen hundred or more. Several years ago I placed a Book of Mormon in the hands of Professor Mills and, while he is reticent as to the parallelism of his discoveries and the Book of Mormon account, he is impressed by the agreement.” James E. Talmage 20 May 1917

Parallels of the Hopewell Culture as described by William C. Mills, Chief Archaeologist of Ohio, with the Book of Mormon“[May 20, 1917; Sunday] Attended Sunday School and afternoon service in Hawthorne Hall, and was a speaker at each assembly. Evening meetings here, as also in Brooklyn, have been discontinued for the summer. The attendance both at Sunday School and afternoon meeting was surprisingly large in view of the fact that many of the Utah college students have left for the vacation period. This evening at the hotel I had a long and profitable consultation with Professor Wm. C. Mills, State Archaeologist of Ohio. He is continuing his splendid work of exploration in the Ohio mounds, and I went over with him again the remarkable agreement between his deductions and the Book of Mormon story. He has reached the following (10) conclusions: The area now included within the political boundaries defining the State of Ohio was once inhabited by two distinct peoples, representing two cultures, a higher and a lower. These two classes were contemporaries; in other words, the higher and the lower culture represented distinct phases of development existing at one time and in contiguous sections, and furnish in no sense an instance of evolution by which the lower culture was developed into the higher. These two cultural types or distinct peoples were generally in a state of hostility one toward the other, the lower culture being more commonly the aggressor and the higher the defender. During limited periods, however, the two types, classes, or cultures, lived in a state of neutrality, amounting in fact to friendly intercourse. The numerous exhumations of human bones demonstrate that the people of the lower type, if not indeed both cultures, were very generally affected by syphilis, indicating a prevalent condition of lasciviousness. Their (are) two peoples or cultures…the lower culture was most commonly the assailing party, while the people of the higher type defended as best they could but in general fled. As a further consequence of this belligerent status they buried their dead, with or without previous cremation, in such condition as to admit of expeditious covering up of the cemeteries by the heaping of earth over the sepulchers [sic], in which hurried work the least skilled laborers and even children could be employed. From a careful collating of data it is demonstrated that the general course of migration through the area now defined as the State of Ohio was inward from the west and outward toward the east. Professor Mills states that no definite data as to the age of these peoples have as yet been found, but that the mounds may date back a few hundred years or even fifteen hundred or more. Several years ago I placed a Book of Mormon in the hands of Professor Mills and, while he is reticent as to the parallelism of his discoveries and the Book of Mormon account, he is impressed by the agreement.” James E. Talmage 20 May 1917

THE HOPEWELL CULTURE

Mounds

We know the Hopewell principally from their mounds. Archaeologists have excavated scores of Hopewell mounds in search of knowledge about these ancient people. Many of these mounds were places of burial and, as a result, we know quite a lot about the Hopewell “way of death.” But the burials and the construction of mounds may only represent the climactic events in a series of activities performed at these special sites.

Before the mounds were built, the Hopewell erected large wooden structures on the site. Some of these structures probably were charnel houses, places where the Hopewell dead were prepared for burial or cremation. Others could have been council houses, places of worship, or all of these things. They may have been used over and over again, as layer upon layer of colored clays and sands sometimes are found covering the floors. Each layer may represent the ritualized ending of one phase of activity and the beginning of another. Often, clay basins were built into the upper most floors and some of these served as crematories.

Once they had fulfilled their role in Hopewell society, whatever that role may have been, the wooden structures were burned to the ground, or carefully taken down. Then these places of ceremony and burial were covered with mounds of earth, some of which were quite large such as those at sites like Seip, Harness, and, the largest, Mound 25 at the Hopewell Mound Group. Mound 25, actually three conjoined mounds, was 500 feet long, 180 feet wide, and 30 feet high when mapped by Squier and Davis in the 1840s.

Sometimes the Hopewell would perform this cycle of activities many times in the same general area. The resulting clusters of anywhere from two to a dozen or more mounds might be enclosed by an elliptical or rounded rectangular earthen wall. At Mound City there are at least 23 mounds of varying shapes and sizes surrounded by the walls of an enclosure.

The people buried in the mounds include males and females, young and old. The Hopewell often cremated their dead, but extended burials in prepared tombs are also common. They often clothed or wrapped the bodies in fine textiles. Sometimes they would bury an array of ornaments and objects of ritual with the dead.

The people buried in the mounds include males and females, young and old. The Hopewell often cremated their dead, but extended burials in prepared tombs are also common. They often clothed or wrapped the bodies in fine textiles. Sometimes they would bury an array of ornaments and objects of ritual with the dead.

The skeletons uncovered by archaeological excavations into Hopewell mounds show us that, in life, these people were healthy and robust. Infant mortality probably was high by today’s standards, but many Hopewellians lived to a ripe old age. The elderly likely held a special place in Hopewell societies. They represented “living archives” of lore on all aspects of the natural and supernatural worlds. Although the Hopewell probably had leaders of some considerable power and influence there is no evidence, such as consistent patterns in burial practices, that their leaders inherited political power after the manner of kings or pharaohs.

The most spectacular offerings frequently were not associated with a particular burial and may, therefore, represent some other ritual activity. Such offerings might include large numbers of copper earspools, copper axes and adzes, plaques of copper or mica cut into various abstract designs or representational forms, animal effigy pipes often carved from Ohio pipestone or other works shaped from various materials brought from the ends of the Hopewell world. These exotic materials included the raw copper and silver from the Lake Superior area; mica, quartz crystal and chlorite from the southern Appalachians; pearls, fossil shark teeth, alligator teeth, conch shells and sea turtle shells from the Gulf Coast; obsidian from the Rocky Mountains; and meteoric iron from various sources. Some archaeologists think these exotic commodities represent a far flung network of trade. But very little material from Ohio, such as tools shaped from Flint Ridge flint, is found at the other end of the so-called Hopewell interaction sphere. Perhaps the trade involved deer skins or other things which have left no traces in the soil for archaeologists to unearth. Perhaps it was not trade at all. Exotic raw materials may have been brought to Ohio by people on pilgrimages or by Ohio Hopewell who collected the materials while on extended quests to far off lands.

Enclosures

The Hopewell people frequently enclosed places of special importance with earthen walls built in diverse shapes and sizes. Squier and Davis originally classified these into two broad categories: works of defense and sacred enclosures. Archaeologists still recognize the basic distinction between hilltop enclosures, with walls that follow the edges of bluff tops, and geometric earthworks which are usually built on broad, flat river terraces. But they no longer interpret most of the hilltop enclosures as defensive works, even though many still bear the name of “fort”. The Fort Ancient site, for example, has more than three miles of embankments with more than 60 passages allowing entry into the enclosure. Ditches, or moats, were dug inside the walls, rather than outside where we might expect to find defensive features. These facts indicate many of the hilltop enclosures were never intended to serve as forts.

The walls of Hopewell enclosures generally were not used to cover burials. Only at the Turner Group of earthworks near Cincinnati and at Mound City have archaeologists recovered burials beneath the walls of an enclosure. Burial mounds occasionally are enclosed by circular or elliptical embankments, but many, perhaps most, of the earthworks were not used for mortuary ceremonialism.

The gigantic earthen enclosures of the Hopewell are among the most compelling and mysterious architectural remains of ancient America. Embankments of earth built in the shape of simple geometric figures or following the contours of a hilltop are the tantalizing vestiges of a sacred landscape molded from Ohio’s soils nearly 20 centuries ago. Most of these earthworks appear to represent places of social, political and religious significance . But it is difficult, if not impossible, to translate this abstract geometry into sure knowledge about the activities and beliefs of the prehistoric builders. Important clues to the function of the earthworks may still lie buried beneath our feet, or may wheel across the sky above our heads.

Ray Hively, a physicist, and Robert Horn, a philosopher, together recently determined the circular enclosures connected to octagons, at Newark and Chillicothe, record in the alignment of their walls the rising and setting points of the moon through an 18.6 year long cycle. Some scholars argue such alignments are coincidental and the Hopewell were not astronomers. But it should not be surprising these people were aware of the cyclical nature of the apparent motions of the moon and sun, nor that they attached importance to these phenomena. Indeed, we should move beyond the question of whether or not the alignments are intentional or accidental. The important question now is, were the earthworks used as instruments for making astronomical observations or, do the astronomically significant alignments of the walls fulfill a strictly symbolic function? In either case, Hopewellian monumental architecture serves to bring the celestial choreography down to earth.

An unexpected precision underlies Hopewellian geometry. Squier and Davis noted a remarkable correspondence between the form and dimensions of earthworks located many miles apart. For example, the circles connected to the octagonal enclosures at both Newark and the High Bank Works in Chillicothe were the same size as the inner of two concentric circles which once graced Circleville. The outer circle at Circleville was the same diameter as Newark’s Great Circle.

There are other important connections between the Hopewell earthworks at Newark and Chillicothe. The Scioto Valley north and south of the modern city of Chillicothe has the largest number and greatest diversity of earthworks built in North America. The Newark Works are the single largest complex of joined geometric earthen enclosures ever built. Octagon State Memorial in Newark and the High Bank Works in Chillicothe are the only two circular enclosures joined to octagons built by the Hopewell and the main axis of these two sites are oriented precisely perpendicular to each other, even though they are more than 50 miles apart.

There is some evidence to suggest the connections between ancient Newark and Chillicothe were formalized in a prehistoric roadway of long, straight parallel walls. Caleb Atwater, one of Ohio’s first archaeologists, suggested in 1820 that the parallel walls which ran southwestward from Newark’s octagon might extend thirty miles or more. In 1862 James and Charles Salisbury, early residents of Newark, traced these walls six miles “over fertile fields, through tangled swamps and across streams, still keeping their undeviating course.” They did not follow the road to its end, but noted the walls headed in the direction of Chillicothe.

There is some evidence to suggest the connections between ancient Newark and Chillicothe were formalized in a prehistoric roadway of long, straight parallel walls. Caleb Atwater, one of Ohio’s first archaeologists, suggested in 1820 that the parallel walls which ran southwestward from Newark’s octagon might extend thirty miles or more. In 1862 James and Charles Salisbury, early residents of Newark, traced these walls six miles “over fertile fields, through tangled swamps and across streams, still keeping their undeviating course.” They did not follow the road to its end, but noted the walls headed in the direction of Chillicothe.

If the Hopewell truly built such a long, straight “roadway” they would not have been the only culture in the Americas to do so; but they would have been among the first. The Anasazi of Chaco Canyon and the Maya of the Yucatan built the most famous networks of long, straight roads more than a century after the Hopewell. The roads of the Maya were ceremonial highways and pilgrimage routes connecting one special place with another. It is often inappropriate to draw analogies between cultures so widely separated in space and time, but perhaps Hopewellian Newark and Chillicothe were great religious centers like Mecca, Santiago de Compostela, or the Vatican. Pilgrims from across eastern North America may have come to these places bearing offerings of rare and precious items; perhaps they left with a spiritual recompense – an oracular message or a religious inspiration. This would provide one of many possible explanations for the presence of large quantities of copper, mica and other exotic materials in Ohio’s mounds and the relative absence of material goods from Ohio in sites at the periphery of Hopewellian influence. See http://www.heathohio.org/about/hopewell.html.

Ancient DNA from the Ohio Hopewell

Amazing results of a study of ancient DNA from the Hopewell site! Lisa A. Mills conducted a study of ancient DNA recovered from human remains from mounds at the Hopewell site, Ross County, Ohio. The results of her work are presented in her doctoral dissertation: Mitochondrial DNA analysis of the Ohio Hopewell of the Hopewell Mound Group. PhD Dissertation by Lisa A. Mills, Department of Anthropology, Ohio State University, 2003.

The Hopewell Mound Group is located in Ross County along the North Fork of Paint Creek, about four miles northwest of Chillicothe. It is part of the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park [http://www.nps.gov/hocu/]. The Hopewell culture [http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=1283] extended across much of eastern North America, but its heartland was here in central and southern Ohio. Hopewell culture sites range in age from 100 BC to around AD 500.

Mills successfully extracted mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from the teeth of 34 individuals originally excavated by H. C. Shetrone who was, at the time, Curator of Archaeology for the Ohio Archaeological and Historical Society (now called the Ohio Historical Society). These human remains were excavated from mounds of the Hopewell Mound Group between 1922 and 1925 and subsequently have been curated by the Ohio Historical Society. Mills sampled a total of 49 individuals so her success rate at recovering DNA was 69%. This rate of success indicates excellent preservation of DNA. Although based on a relatively small sample of individuals, the results are promising and provocative.

First, Mills noted that the people she studied from the Hopewell site represented a very diverse group. The sample included 4 out of the 5 documented Native American lineages (haplotypes) [see http://www.centerfirstamericans.com/mt.php?a=203 and http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haplogroup_X_(mtDNA) for more information about Native American DNA]. This apparent diversity might suggest that individuals from different groups were buried together in these mounds.

Second, comparisons between the mtDNA from individuals from the Hopewell site and a database of mtDNA from groups from all over the world, demonstrated that these ancient Native Americans shared close ties with Asia especially, China, Korea, Japan, and Mongolia. This offers strong support for the already well-supported conclusion that Native Americans originated in Asia and migrated to the Americas in the past 15,000 years.

Third, comparisons between the mtDNA from these individuals from the Hopewell site and a database of mtDNA samples from 50 ancient and modern Native American groups provided evidence of some biological relationships. There were clear links between these people and individuals from two Adena culture [http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=1287] sites as well as individuals from the even earlier Glacial Kame culture [http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=2049]. This confirms the inference that the people of the Hopewell culture were the descendants of people of the Adena culture (circa 800 BC to AD 1) who were, in turn, descended from the local Archaic cultures (circa 3000-500 BC).

Interestingly, however, the Hopewell site individuals did not show a close relationship to the Fort Ancient culture samples [http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=1285]. Perhaps, as some scholars have suggested, some Fort Ancient-era groups (circa AD 1000-1650) moved into Ohio from elsewhere. The most closely related ancient groups outside of Ohio included individuals buried at the 700-year-old Norris Farm mound in central Illinois. Also, Mills found that one particular female buried at Mound 25 at the Hopewell site had a rare mutation that she shared with several elite individuals buried at the 1000-year-old Cahokia site [http://www.cahokiamounds.com/cahokia.html].

Modern groups with whom the individuals at the Hopewell site shared some degree of relatedness include the Chippewa/Ojibwa [http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/entry.php?rec=2090] and Kickapoo of the Great Lakes region. Some genetic links also are indicated between one or more of the individuals from the Hopewell site and tribes as diverse and widespread as the Apache, Iowa, Micmac, Pawnee, Pima, Seri, Southwest Sioux, and Yakima. Mills looked, in particular, for evidence of ancestral ties between the individuals at the Hopewell site and Cherokee Indians, since some oral traditions have suggested a relationship between them. She found that Cherokee mtDNA samples do not cluster close to the Ohio Hopewell.

Finally, Mills found that multiple burials at the Hopewell site included individuals with different mtDNA profiles, indicating they did not share a recent female ancestor (since mtDNA is passed from mother to child). This further indicates that the people at this Hopewell culture site did not base their burial practices on principles of matrilineal descent. Due to the small sample size, the conclusions are tentative.

Mills work, however, confirms that DNA is recoverable from 2,000-year-old bones and that it can be used to make inferences about biological relationships between and among ancient populations and their descendants. It also demonstrates the importance of museum collections, including ancient human remains.

Posted June 22, 2006 by: Brad Lepper

Mitochondrial DNA analysis of the Ohio Hopewell of the Hopewell Mound Group. PhD Dissertation by Lisa A. Mills, Department of Anthropology, Ohio State University, 2003. CHAPTER 6 CONCLUSION

“The results of this study add to an already growing body of research dedicated to mtDNA analysis. In recent years, research utilizing Y- chromosome and STR analysis have also begun to add to what is known about the genetic variation present in Native Americans both ancient and modern. Combine that information with mtDNA, and a complete picture of migration, gene flow and kinship begins to take shape in North America. The Ohio Hopewell through an analysis of their mutations have revealed ancestral relationships with individuals in China, Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Mongolia, Russia and South America. The Ohio Hopewell also display mutations that are uniquely their own, such as haplotype A 16166, haplotype B 16247 and 16265. The unique mutations of the Ohio Hopwell of Hopewell Mound Group may have been lost through attrition or have yet to be discovered in other Native American populations. The Ohio Hopewell also share a unique mutation with the Cahokians of 72Sub2 Mound , utilized to denote a rare haplotype aligned with individuals of high status at Cahokia.

“The results of this study add to an already growing body of research dedicated to mtDNA analysis. In recent years, research utilizing Y- chromosome and STR analysis have also begun to add to what is known about the genetic variation present in Native Americans both ancient and modern. Combine that information with mtDNA, and a complete picture of migration, gene flow and kinship begins to take shape in North America. The Ohio Hopewell through an analysis of their mutations have revealed ancestral relationships with individuals in China, Korea, Japan, Taiwan, Mongolia, Russia and South America. The Ohio Hopewell also display mutations that are uniquely their own, such as haplotype A 16166, haplotype B 16247 and 16265. The unique mutations of the Ohio Hopwell of Hopewell Mound Group may have been lost through attrition or have yet to be discovered in other Native American populations. The Ohio Hopewell also share a unique mutation with the Cahokians of 72Sub2 Mound , utilized to denote a rare haplotype aligned with individuals of high status at Cahokia.

Phylogenetic analysis through Neighbor Joining trees revealed that the Ohio Hopewell group with those individuals who share the basic A through D Native American haplotypes. Upon closer examination, the Ohio Hopewell clustered with both ancient and modern groups of Native Americans. RFLP Neighbor Joining trees revealed that the Ohio Hopewell do not group with samples from Fort Ancient populations of the Ohio River Valley, but with samples from Glacial Kame, Adena or Norris Farms, possibly indicating some relationship between the groups. This in part could be due to small sample size and a low number of sites that have been amplified. More work within all of the Ohio River Valley cultures is needed to give a clearer picture to archaeologists, linguists and biological anthropologists alike. Also examined were hypotheses detailing the migration of the Glacial Kame/Red Ocher groups into the northeast. The Ohio Hopewell did not supply evidence to support these hypotheses. This research did add to the growing body of work on the Hopewell. Matrilineal descent at least at the Hopewell Mound Group is not supported by this research. Also, based upon a visual analysis of the mtDNA haplotypes at the Hopewell Mound Group, as well as lack of homogeneity in multiple burials, segregation does not seem to be occurring at the site. More analysis is needed for the remaining burials in order to flesh out the rest of the site and compare the patterns. Finally, genetic indices were produced which present the Ohio Hopewell as a diverse and heterogenetic group, possessing four out of the five possible Native American haplotypes and presenting as an expanding population. This information also adds to the debate of the number of original waves of Native Americans to migrate into the North America. The Ohio Hopewell would suggest only one wave containing all the haplotypes that are present today in modern Native American populations. Finally, this research provides a model for multidisciplinary research, drawing from all four fields of anthropology. Each field complementing the work of the other fields to produce a complete picture. However, due to the small sample size and restriction to mtDNA, future work could add to what is already known about the Ohio Hopewell.

Contributions were also made in the struggle to deal with the bane of ancient DNA work, contamination. The procedure outlined in this research could help preserve information thought lost to contamination.”

Notes about Haplogroup X documentation

Brown M, Hosseini S, Torroni A and et al. (1998) MtDNA haplogroup X: An ancient link between Europe/Western Asia and North America? A J Hum Genet 63: 1852-1861.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002929707616292

Introduction

For Native Americans, extensive RFLP and control region (CR; also known as the “D-loop”) sequence analysis has unambiguously identified four major founding mtDNA haplogroups, designated “A”–“D” (Torroni et al. 1992; 1993a). Together, these haplogroups account for ∼97% of modern Native American mtDNAs surveyed to date (Torroni and Wallace 1994; Merriwether et al. 1995). Apparent non–haplogroup A–D mtDNAs can result from reversion of key A–D markers, recent admixture with non–Native Americans, or represent additional Native American founding mtDNA lineages. A striking example of the presence of non–haplogroup A–D genotypes in Native Americans can be seen in the Ojibwa, an Amerindian population from the Great Lakes region of North America. Using high-resolution RFLP analysis, Torroni et al. (1993a) found that 25% of the northern Ojibwa mtDNAs did not belong to haplogroups A–D and that nearly all of these “other” mtDNAs encompassed four distinct but related haplotypes characterized by the RFLP motif −1715 DdeI and +16517 HaeIII. This motif was also present in 4% of the Navajo, but it was not observed in 18 other tribes from North, South, and Central America. The high incidence of this motif in the Ojibwa has been confirmed recently by Scozzari et al. (1997), who reported its presence in 26% of the southeastern Ojibwa from Manitoulin Island, Canada.