Cities, Highways and Roads of the Book of Mormon

“And it came to pass that there were many cities built anew, and there were many old cities repaired. And there were many highways cast up, and many roads made, which led from city to city, and from land to land, and from place to place. And thus passed away the twenty and eighth year, and the people had continual peace.”3 Nephi 6:7-9

Alma 48:8 “Yea, he had been strengthening the armies of the Nephites, and

erecting small forts, or places of resort, throwing up banks of earth round about to enclose his armies, and also building walls of stone to encircle them about, round about their cities and the borders of their lands, yea, all round about the land.” (See blog here about stone walls in North America)

Why This Subject?

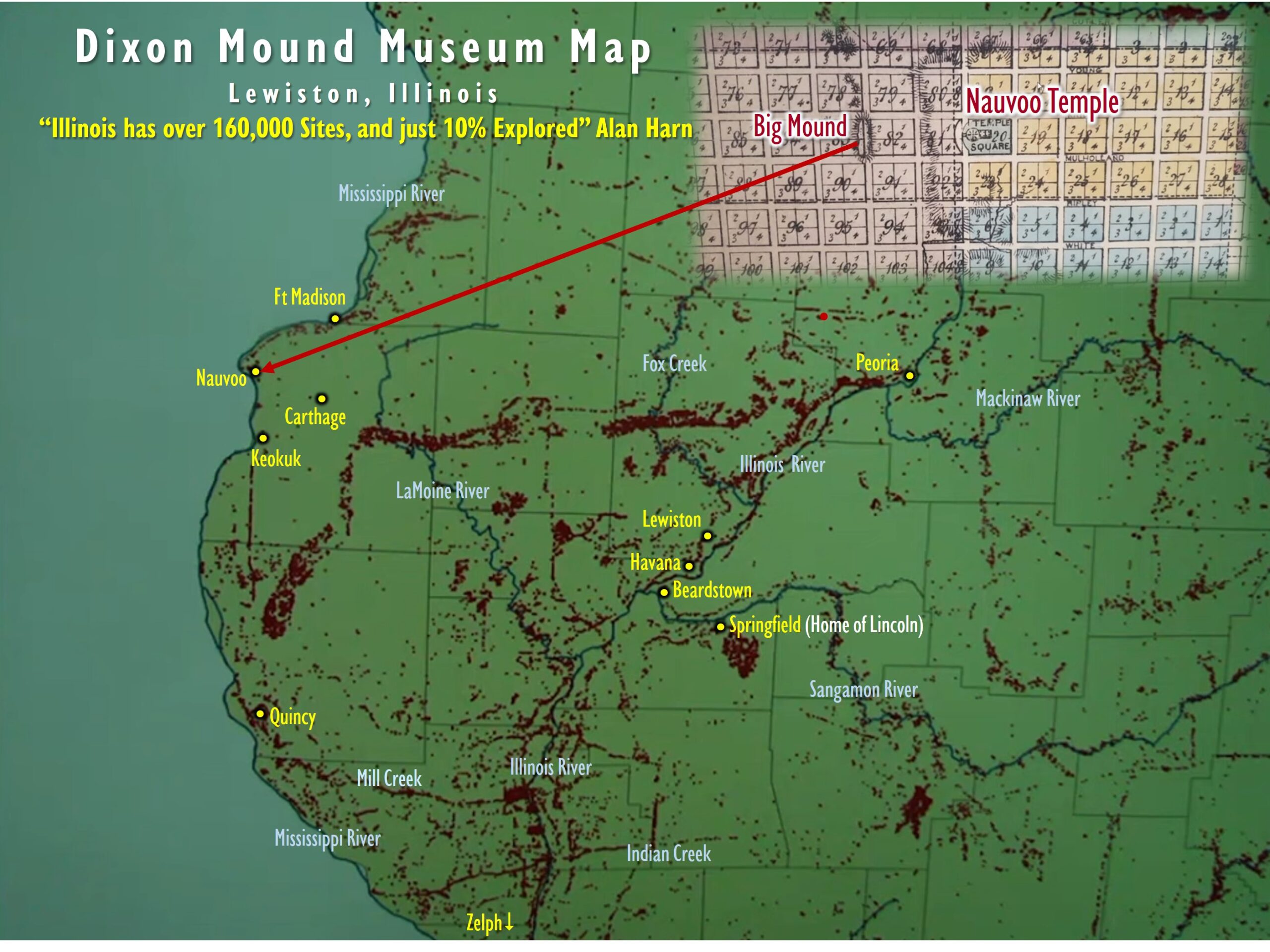

Many advocates of the Mesoamerican theory claim there is a lack of large cities, and remnants of highways in the Heartland Model. After reading this blog you will have many evidences that cities, villages, roads, and highways were prevalent in the Heartland of North America. We will discuss roads, hightways, cities, and building materials to help you research more about the Nephites who lived in the Heartland of North America.

Building = Big Town of Bare Earth

Dr. Roger Kennedy, the former director of the Smithsonian’s American History Museum, addressed a misperception about earth mounds, noting that earth mounds are actually buildings.

Build and building are also very old words, often used in this text [his book] as they were when the English language was being invented, to denote earthen structures. About 1150, when the word build was first employed in English, it referred to the construction of an earthen grave. Three hundred and fifty years later, an early use of the term to build up was the description of the process by which King Priam of Troy constructed a “big town of bare earth.” So when we refer to the earthworks of the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys as buildings no one should be surprised.” The Mormons and the Mounds by Jonathan Neville MHA Presentation June 2017 St. Louis, Missouri

Buildings of Cement and Wood and Dirt

“And I did teach my people to build buildings, and to work in all manner of wood.” (2 Nephi 5:15) “And the people who were in the land northward did dwell in tents, and in houses of cement, and they did suffer whatsoever tree should spring up upon the land that it should grow up, that in time they might have timber to build their houses, yea, their cities, and their temples, and their synagogues, and their sanctuaries, and all manner of their buildings.” (Helaman 3:9)

“Everyone knows that Mesoamerica features impressive cities and structures made of stone and cement. I’ve visited many of them. Back in the day, many of these sites were completely open, with no guards or even fences. You could climb all over them, and I have.

Mayan culture is fascinating, and we’re learning more and more about it all the time. My kudos to all the Mesoamerican archaeologists and linguists who are helping us understand that culture. But it has nothing to do with the Book of Mormon.

The M2C [Mesoamerican 2 Hill Cumorah Theorists] intellectuals want people to believe that two brief references in the Book of Mormon describe the massive Mayan stone-and-cement structures throughout Mesoamerica.

Naturally, the Mayans built with stone and cement. In a jungle, wood structures don’t last long.Which explains how we know the Nephites did not live in a jungle. The Nephites built with wood and cement, not stone and cement.” Jonathan Neville Blog Here

City doesn’t have to be large

“A city need not have a large population. “Many ancient cities had only modest populations, however (often under 5,000 persons).”[i] When Lehi left Jerusalem, the city had a population of only about 25,000 people.[ii]

Roger Kennedy discussed the terms “city” and “building” this way.

Our English noun city comes from the Latin… city carries from its demographic root the implication of intention. A city was the consequence of a purpose. Perhaps it is not so much a noun as the outcome a verb; not a location but a phenomenon. A city was where a relatively large number of citizens congregated… In the Middle Ages, in the British Isles, a city became a place in which a potent religious leader such as a bishop was headquartered.[iii]

The cities described by the text fit Kennedy’s concept quite well. There is no requirement for massive stone temples and palaces. Such are never mentioned in the text. The only palace described in the text was Noah’s, and it was made “of fine wood,” not stone (Mosiah 11:9).” Jonathan Neville Moroni’s America page 131

[i] Michael E. Smith, “Ancient Cities,” The Encyclopedia of Urban Studies (R. Hutchison, ed., Sage, 2009): 24. Available at http://bit.ly/Moroni75.

[ii] John W. Welch and Robert D. Hunt, “Culturegram: Jerusalem 600 B.C.,” Glimpses of Lehi’s Jerusalem (Foundation for Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS), Provo, Utah 2004): 5.

[iii] Kennedy, Ancient Cities, p. vii.

“Ancient people almost never built of stone”

“The Nephites vastly preferred wood to any other building material, and only worked in cement when they were forced to by shortage of timber. Indeed, they refused to settle otherwise good lands in the north if timber for building was lacking (Helaman 3:5). Where they reluctantly settled in unforested areas they continued to “dwell in tents, and in houses of cement,” while they patiently waited for the trees to grow (Helaman 3:9). Since cement must be made of limestone [see. p. 63], there was no lack of stone for building in the north. Why then did they not simply build of stone and forget about the cement and wood? Because, surprising as it may seem, ancient people almost never built of stone. Even when the magnificent “king Noah built many elegant and spacious buildings,” their splendor was

that of carved wood and precious metal, like the palace of any great lord of Europe or Asia, with no mention of stone (Mosiah 11:8-9). The Book of

Mormon boom cities went up rapidly (Mosiah 23:5; 27:6), while the builders were living in tents. And these were not stone cities: Nephite society was even more dependent on forests than is our own” – Hugh Nibley, An Approach to the Book of Mormon, 2nd Edition, Chapter 29,

Building Materials, Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co. [1964]. As quoted in Annotated Book of Mormon page 349

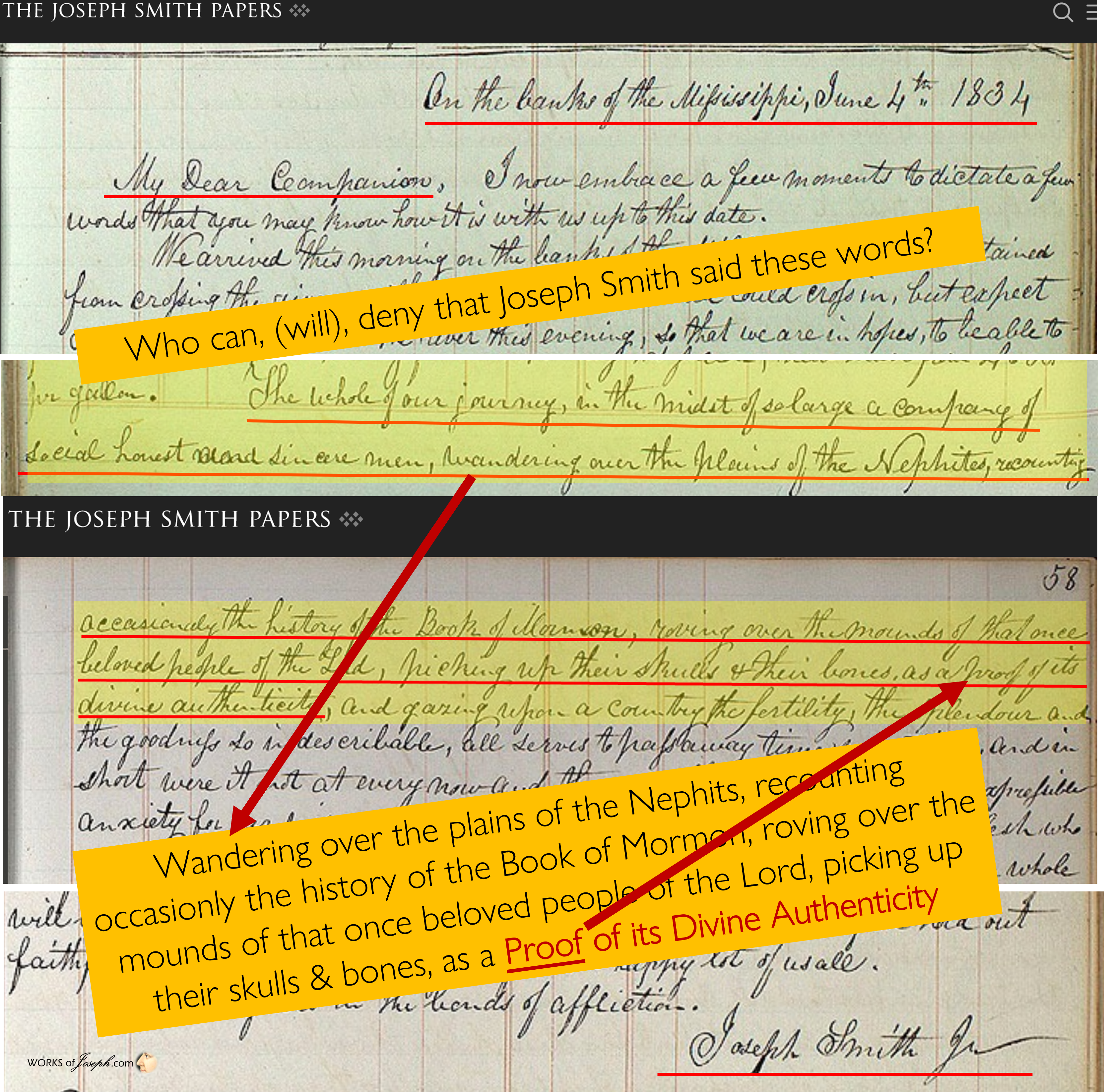

Joseph Smith on Buildings

Lucy Mack Smith said, “During our evening conversations, Joseph would occasionally give us some of the most amusing recitals that could be imagined: he would describe the ancient inhabitants of this continent; their dress, mode of travelling, and the animals upon which they rode; their cities, and their buildings, with every particular; he would describe their < mode of > warfare, as also their religious worship. This he would do with as much ease, seemingly, as if he had spent his whole life with them” – Lucy Mack Smith, “Lucy Mack Smith, History, 1845,” p. 87, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed Feb. 5, 2019.

“HIDDEN CITIES” IN NORTH AMERICA

“The Lord told us, in reply that he would make it known to the people that the early inhabitants of this land had been just such a people as they were described in the book, [of Mormon] and he would lead them to discover the ruins of great cities…” – David Whitmer, Interview with James H. Hart (Richmond, Mo., 21 August 1883), as printed in Deseret Evening News, Salt Lake City, Utah [Tue, Sep 4, 1883], page 2; emphasis added.

Roger G. Kennedy, Director Emeritus, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, author, “Hidden Cities, The Discovery and Loss of Ancient North American Civilization,” The Free Press, New York, [1995], stated, “Very, very few of us were conscious of these immense cities of a place like Monk’s Mound and Cahokia, opposite St. Louis, which is bigger in its footprint than the Great Pyramid at Giza [city in Egypt]. We didn’t know that.”

Dr. Kennedy coined the phrase, “Hidden Cities,” because he states, “I use the term because these were very big places. There were more people, that we now know, in Cahokia, across from St. Louis, than there were in London or Rome. There were major population centers in what is now Nashville and Cincinnati and Pittsburgh and St. Louis. Few realize that some of the most complex structures of ancient archaeology were built in North America, home of some of the most highly advanced and well organized civilizations in the world.” In his book, Hidden Cities, he writes: “Eighteenth century pioneers passing over the Appalachians into the Ohio Valley wrote often of [the] feeling of being freed of encumbrances, of fresh beginnings. Judging from what they said, and from what has been said of them subsequently, most of them shared the misconception that they were entering an ample emptiness intended to be theirs alone.

“In fact… [t]he western vastness was not empty. Several hundred thousand people were already there, and determined to resist invasion….Even along the headwaters of the Ohio, on the banks of mountain brooks, there were signs of ancient habitation…As the streams grew larger, so did the buildings. “In the Ohio and Mississippi valleys, tens of thousands of structures were built between six and sixty-six centuries ago. Some, as large as twenty-five miles in extant, required over three million person hours of labor” – Roger G.Kennedy, Hidden Cities, 1-2. City of Cahokia by William R. Iseminger Courtesy of Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site

Ancient Hopewell Road

“Although Cahokia, the great Mississippian-era city in Illinois, qualifies as a city under almost any definition, archaeologists generally do not regard the large Hopewell earthworks as “cities.” Roger, however, was expansive in his definition: “by city we mean a place in which a large number of people gather for common purposes.” Therefore, he was perfectly justified in encompassing Ohio’s Fort Ancient, the Newark Earthworks, Mound City and Serpent Mound within his marvelous narrative.

In 1990, I was a relatively new curator at the Newark Earthworks State Memorial. Roger, with characteristic flair, referred to me in his book as “chatelaine” for the earthworks. (I still wish I could make that my official job title!) Roger and his film crew interviewed me at the Munson Springs site, a Paleoindian camp site between Granville and Newark, as well as at the Newark Earthworks. We also enlisted a troop of local boy scouts and experimented with (mostly) aboriginal tools to see how long it would take to build the earthworks. (It turns out a motivated team of young men can move a lot of earth in a surprisingly short period of time!) Roger became interested in the idea of the Great Hopewell Road, which I was then only beginning to formulate; and he decided we needed to rent a helicopter and fly the route. So he arranged for the helicopter and we did just that. It was August, so we didn’t see much through the morning haze except a profusion of vegetation,but Roger became convinced that a Hopewell Road did, indeed, connect Newark and Chillicothe and even extended on to Portsmouth! I have never been willing to go that far literally or figuratively, but I agree that if there was a Great Hopewell Road connecting Newark and Chillicothe, there should be other Hopewell roads connecting other great Hopewell earthwork sites.” “Ohio History Connection

Hopewell Road Documentary, Introduction

Introduction Video Here:

This is the introduction to Searching for the Great Hopewell Road by American Public Television. It gives a brief overview of the highly advanced ancient civilization, called by archaeologists today the Hopewell Mound Builders, that existed in the heartland of North America between about 300 B.C. and abruptly ended near 400 AD. To purchase the DVD documentary, please visit our bookstore at www.BookofMormonEvidence.org

The Great Hopewell Road Intro Video

LiDAR Imaging of the Great Hopewell Road

Great Hopewell Road

The Great Hopewell Road is thought to connect the Hopewell culture (100 BCE-500 CE) monumental earthwork centers located at Newark and Chillicothe, a distance of 60 miles (97 km) through the heart of Ohio, United States. The Newark complex was built 2,000 to 1800 years ago.[1]

In 1862, brothers Charles and James Salisbury surveyed the first 6 miles (9.7 km) of this road, noting it was marked by parallel earthen banks almost 200 feet (61 m) apart and led from the Newark Earthworks. They said that the road extended much farther south from Newark in the direction of Chillicothe. Other 19th-century investigators, such as Ephraim G. Squier and Edwin H. Davis, also documented the walls of the road near Newark. The 2.5-mile section from the Newark Octagon south to Ramp Creek is now known as the “Van Voorhis Walls”.[1]

In the 1930s, the area was surveyed by plane, revealing traces of the road extended for 12 miles (19 km) toward the Hopewellian center of present-day Chillicothe. Additional examination of the area with the new sensing technology of LiDAR (Light Detection And Ranging) adds confirmation to this finding and suggests a way to gain more evidence. This technology showed the road was lower than the surrounding land, sunk between the walls.[1]

Dr. Brad Lepper, the present-day champion of the Great Hopewell Road, claims that traces of the road remain at four additional places along the 60-mile (97 km) line connecting Newark and Chillicothe. Parts of the road can be seen from the air and with infrared photography. There is precedent for such a sacred road at other complexes.[2] More “ground truthing” needs to be performed but the evidence is suggestive.[1]

The first 2.5 mi south of the parallel-walled roadway of the Newark Earthworks is known as the Van Voorhis Walls. It is a confirmed earthwork. This portion of the earthwork terminates a Ramp Creek, in Heath, Licking County, Ohio. South of there, the projected path of the Hopewell Road passes through fields toward Millersport, Licking County, Ohio. Evidence from early accounts and 1930s aerial photography suggests that the Hopewell Road may continue south of Ramp Creek, and a cultural resource management study provides equivocal, yet suggestive evidence of the earthwork south of Ramp Creek. In 2016, an analysis of previous studies found enough evidence of the Great Hopewell Road south of Ramp Creek, to indicate that archaeologists should continue to search for evidence of it.Great Hopewell” Wikipedia/Hopewell road

“Graded Ways”

Understanding the roads and highways spoken of in the Book of Mormon, it would be helpful to know what term for those words are used in the history and archaeology of today that may help us study them. I just discovered that perfect wording used in the 1800 text of those archaeologists. They called a highway or road a “graded way.” It also seems the ancient mound builders would settle in places that seemed as naturally graded ways where they could slightly modify and take advantage of their usage.

Archaeological History of Ohio: The Mound Builders and Later Indians By Gerard Fowke Page 271

CHAPTER VIII

GRADED WAYS, TERRACES, EFFIGIES, AND ANOMALOUS STRUCTURES.

A. —GRADED WAYS.

ON page 209 is a description of the possibly artificial grade at the Turner Group. So far as known, no other passageway is formed by making a fill to connect plains of different levels.

But at several places in Ohio gentle inclines through a depression, from a higher terrace to a lower, or to a stream, are attributed to the Mound Builders, who are supposed to have cut them out for roadways, throwing the earth to either side. Squier and Davis have the following reference to them.

There is a singular class of earthworks, occurring at various points at the West, * * the purposes of which to the popular mind, if not to that of the antiquarian, seem very clear. These are the graded ways, ascending sometimes from one terrace to another, and occasionally descending towards the banks of rivers or water-courses. The one at *Marietta, is of the latter description; as is also that at Piqua, Ohio. One of the former character occurs near Richmonddale, Ross county, Ohio; and another, and the most remarkable one, about one mile below Piketon, Pike county, in the same State. A plan and view of the latter is herewith presented. [ See figure 75 (S. & D., 88, plate XXXI, No. 1) ]. It consists of a graded way from the second to the third terrace, the level of which is here seventeen feet above that of the former. The way is ten hundred and eighty feet long by two hundred and fifteen feet wide at one extremity, and two hundred and three feet wide at the other, measured between the bases of the banks. The earth is thrown outward on either hand, forming embankments varying upon the outer sides from five to eleven feet in height; yet it appears that much more earth has been excavated than enters into these walls. At the lower extremity of the grade, the walls upon the interior sides measure no less than twenty-two feet in perpendicular height.

It is, of course, useless to speculate upon the probable purpose of this work. At first glance, it seems obvious; namely that it was constructed simply to facilitate the ascent from one terrace to another. But the long line of embankment extending from it, and the manifest con nection which exists between it and the mounds upon the plain unsettle this conclusion.” — S. & D., 88-9.

A. AT MARIETTA.

Of the four mentioned by them, that at Marietta has been most often described; but only because more people have seen it. Among the earlier notices, these may be found:—

“A causeway forty yards wide, and from ten to twelve feet high, rounded like a turnpike road, leads from it to the river.” — Cuming, 106.

In a numbered sketch, made in 1785, of the Marietta works, is given:—

“No. 6, Conveyed away from the town to the then locality of the river, which is supposed at that time to have run along the edge of the second bottom. These walls are now twenty feet high, and the graded road between them was one hundred feet wide, and beautifully rounded like a modern turn-pike.” — Stebbins, 329.

“The entrances at the middle are the largest, particularly that on the side next the Muskingum. From this outlet is a covert way, formed of two parallel walls of earth, 231 feet distant from each other, measuring from centre to centre. The walls at the most elevated part on the inside are 21 feet in height and 42 feet in breath at the base, but on the outside average only five feet high. This forms a passage about 360 feet in length, leading by a gradual descent to the low grounds, where it probably at the time of its construction reached the margin of the river. Its walls commence at sixty feet from the ramparts of the fort, and increase in elevation as the way descends towards the river; and the bottom is crowned in the centre in the manner of a well-formed turnpike road.” — Harris, 149.

The account by Squier and Davis is more complete.

The “ Via Sacra,” or graded way, at Marietta (top picture) “is six hundred and eighty feet long by one hundred and fifty wide between the banks, and consists of an excavated passage descending regularly from the plain, upon which the works just described are situated, to the alluvions of the river. The earth, in part at least, is thrown outward upon either side forming embankments from eight to ten feet in height. The centre of the excavated way is slightly raised and rounded, after the manner of the paved streets of modern cities. The cross-section gh [see figure 15] exhibits this feature. Measured between the summits of the banks, the width of the way is two hundred and thirty feet. At the base of the grade, the walls upon the interior are twenty feet high. From this point there is a slight descent, for the distance of several hundred feet to the bank of the river, which is here thirty-five or forty feet in height. [There is an] entire absence of remains of antiquity upon the beautiful terraces to which this graded passage leads. They may nevertheless have been once as thickly populated as they are now; and this passage may have been the grand avenue leading to the sacred plain above, through which assemblies and processions passed, in the solemn observances of a mysterious worship.”— S. & D., 74.

The plan given does not represent the squares as ” exact “. Whittlesey is less romantic in his explanation of its probable use:—

‘”The grade at Marietta leads from a strong work down to the Muskingum River, and had an evident purpose, that of access to water. It is principally an excavation and not an embankment.” — Whittlesey, Works, 9.

There is no doubt that this work is artificial; but it was never made for the sole purpose of being used as a roadway or means of passage between the two terraces. It is wide enough for a hundred men to walk abreast in it, and leads out on a strip of bottom land but little if any wider than itself and which could never have been much wider. It is more than likely that earth was obtained here for making mounds and embankments in the vicinity. Very probably it originated in a pathway to the river, which was gradually widened by removal of earth for the works. If this was the case, another path led from the lower terrace to the water. The stream may have been reached, however, through the ravine which discharges almost in a line with the upper side of the “Via Sacra “.

It is to be observed that the earliest recorded measurement gives the height of the walls on each side of the cut, as only five feet. The scale of “twenty feet” for the inside, includes the undisturbed earth of the side-slopes. These walls, which long ago disappeared, were probably built of earth taken up from the surface of the upper terrace, as was the case at Piketon.

The water of the Muskingum is now at a much higher level than it was formerly, owing to the dam near the mouth; but if ever as low as denoted by Squier and Davis, it is very clear that the graded way was made without any reference to the stream.

B. AT RICHMONDDALE.

No such work exists in the vicinity of this village; nor is there any visible evidence of aboriginal occupation about there, except a few mounds scattered over the high terrace to the north. None of the latter are within a mile of Richmonddale; and there is no conceivable reason why a “graded way” should be made, when there is no place for it either to begin or end. Probably the authors allude to some one of the numerous ravines in which no water now flows on account of changes of slope carrying drainage in other directions.

C. AT PIQUA.

The reference to this is based upon Major Long’s observations early in the century. It is evident we have here to deal only with a natural ravine or gulley, on one side of which an embankment has been made.

At Piqua, “near the bank of the river, there are remains of a waterway; these remains consist of a ditch dug down to the edge of the river, the earth from the same having been thrown up principally on the south side or that which fronts the river; the breadth between the two parapets is much wider near the water than at a distance from it, so that it may have been used either for the purpose of offering a safe passage down to the river, or as a sort of harbor in which canoes might be drawn up; or perhaps, as is most probable, it was intended to serve both purposes. This waterway resembles, in some respects, that found near Marietta, but its dimensions are smaller. The remains of this work are at present very inconsiderable, and are fast washing away, as the road which runs along the bank of the river intersects it, and, in the making of it, the parapet has been leveled and the ditch filled up.” — Long, St. Peter’s, 52.

D. AT PIKETON.

The work at Piketon has long been cited as the most remarkable instance of this form of aboriginal industry. Figure 76 from the original drawing by Squier and Davis, and reproduced in a hundred publications since their time, has always been given as a correct representation. The actual work is shown in figure 77, in plan and section, from a recent careful survey. It will be seen that there is no ” crown ” to the roadway, as their cross-section shows, except that which is due to the construction of a turnpike passing through it; and the error and exaggeration, in various other respects, of their “plan and view” will be apparent at a glance. In itself the work is of no special interest or importance, and the details are trivial: but they show a negligent, slip-shod manner which casts doubt on more important work, and should be gone into with some minuteness, because these perverted accounts have done much toward impressing readers with erroneous ideas of the people who are credited with its formation. Compare the “view” with the sections.

The depression is not in any degree artificial but is due entirely to natural causes. Formerly, when Beaver creek was at a much higher level than its present bed, at least a part of its waters found their outlet through this cut-off or thoroughfare. Its length, following the curve from the creek bank to the lower terrace at the other end, is 2225 feet; at the narrowest part it measures 120 feet across. The elevation of the upper terrace above the lower is 22 feet—not 17. The greatest base measure of either wall is 69 feet; one of them is 636 feet, the other 761 feet, in length along the top. The east wall has been cultivated until not more than three feet high; the west wall is untouched, and only a few rods of it have an elevation of more than six feet. Instead of tapering to a point at the south end, the west wall is higher there than anywhere else, having the appearance of a mound with an elevation of nine feet. No earth was carried up out of the depression; that composing the walls was gathered on the surface and piled along the brink of each bank, a part of it being allowed to spread down the sides in order to produce a steeper slope. Both walls change direction at more than one point; and so far from extending its entire length on the upper terrace, the east wall descends the slope and terminates near the bottom. The measure of ” 1080 feet” so frequently found in other parts of Squier and Davis’s descriptions, as well as here, will not apply to any part of the “graded way” unless the line be carried out into the open fields. If the walls were leveled and all the earth in them spread out evenly, it would not make a difference of more than two feet in the elevation of the space between them.

The early mistakes in regard to this work are repeated and exaggerated by McLean. Whittlesey says:—

“The great excavated road at Piketon also descended to water.” — Whittlesey. Works, 9.

While, as we have seen, it is not “excavated” by human labor, it undoubtedly once “descended to water,” though not in the sense he means to convey. It is cut through the fourth or highest terrace, and terminates on the third, at the end toward the river, which then flowed at that level. When Beaver creek carved out its present channel, the old thoroughfare remained practically unchanged for an unknown number of centuries, until the Mound Builders came along and built their little walls on either side, all unconscious of the trouble they were making for future archaeologists.

E. ABOVE WAVERLY.

Colonel Whittlesey falls into a worse error concerning another old ” cut-off “. This was made by the Scioto, after the third terrace was formed. It would be difficult indeed to ” discover the spot to which the earth was transported “, as it has gone toward making low bottoms farther down the river. He describes it as an excavation in Big Bottom, “near the line between Pike and Ross counties. The design appears to have been to form a cut or passage from the bottom land above Switzer’s Point to the bottom land below. Only a very small portion of the earth removed is now to be seen; having been transported to some spot which I did not discover. At the northeast end of the east bank is a mound. A little to the west and northwest is a natural ridge which appears to have been trimmed by art, and to have been used in connection with the lower portion of the western line of the embankment. The mass of earth removed here is greater than at Piketon.” — Whittlesey, Works, 7.

F. NEWARK.

“There is also a grade, partly in excavation and partly in bank, from a portion of the Newark works in Licking county, leading to a branch of Licking or Pataskala river.” — Whittlesey, Works, 9. This has been described under the Newark enclosures.

G. NEAR BOURNEVILLE.

Atwater alludes to the “graded way to the spring” at the ellipse described on page 217.— Atwater, 149.

It never appears to occur to these writers that the existence of springs, and of an easy approach to them, may have determined the location of earthworks. They seem to proceed upon the assumption that the builders made their enclosures at random, and then set to work to make the locality habitable.

H. AT MADISONVILLE.

“The ancient roadway near Madisonville, is cut along the face of a steep hill extending from the creek to the top of the hill. It is upward of 1,600 feet in length, having an average width of twenty-five feet.” — Howe, II, 23, condensed.

The only “ancient roadway” at this place is an old wagon road, now overgrown with trees and partially destroyed. It is not at all like any prehistoric work, either in its position or its construction. It begins in a ravine and ends at the top of the hill near a pioneer farmhouse; and there are no aboriginal remains anywhere near it.

I. NEAR CARLISLE.

McLean describes with much minuteness a “graded way,” about two miles west of Carlisle in Butler County. This is raised instead of sunken. He traces it from the top of a hill, down the slope, across a bottom or “upper terrace” to the bank of Twin creek, giving numerous measurements. Here it stops; but he imagines it as formerly extending across the “second terrace,” which was probably a “swamp” at one time and needed this “causeway” in order to enable the Mound Builder to reach the fort from which the “graded way” proceeds. He attempts to establish a chronology, by supposing all this “swamp” to have been carried away by erosion, to the level of the “second terrace,” which he places thirty-one feet below the “upper terrace.” No definite number of years is given, because there is no measure of erosion, and so

“The question is, ‘how long has it taken Twin Creek to cut the thirty-one feet?'”— McLean, 134.

The site of this professed artificial roadway is on a hillside overlooking the valley of Twin creek, and on the bottom land at its foot. Two nearly parallel deep ravines, a few hundred feet apart, form a headland with steep, almost precipitous, sides. Around the margin of this and across the rear end of it an embankment is carried. On the side toward the creek it curves inward to surround the head of a small ravine which affords an easy approach from the bottom land below; consequently there is no need for a “graded way,” and none was ever made. The ridge described as such is entirely a natural formation, due to erosion. The upper portion preserves the ordinary slope of the ground, as may be understood from his measurement which gives an incline of more than twenty degrees. This does not sound large, but makes a pretty stiff climb, nevertheless. That part of the “way” along the foot of the hill is due to the approach of the ravine on one side toward a shallow washout on the other. What McLean calls the continuation of this “graded way” across the bottom, or “upper terrace,” is nothing but the ridge formed by an old fence row and by the earth thrown up in making a turn with a plow at the end of the field; it is visible only in some places, as he says, and never had any existence where it is not now to be seen. His “second terrace” is nothing but the shore of the creek, and is subject to overflow with every hard rain — unless, indeed, he means the low bottom beyond the creek. This may once have been a “swamp,” as he suggests; but if so it existed before the stream was formed, and extended to the hills several hundred yards away. If the Mound Builder was here at that time, he saw the retreat of the ice-sheet; for it was very shortly after that time that Twin creek began its task of “cutting down the thirty-one feet.”

In a word, it may be said that with the single exception at Marietta, the alleged “excavated graded ways” are natural depressions, possibly slightly modified, which happened to be where they were needed; or the place was taken possession of because the grade was there. The few pathways which are actually artificial have escaped notice by reason of their insignificance. Where a group of works or a village-site is located on a terrace immediately above a very steep slope, steps were no doubt cut in the bank, or perhaps a narrow passage way dug, to facilitate ascent. The depression thus begun would deepen and widen with every storm, until finally a trough with considerable width and easy slope would be eroded, which can be distinguished from one entirely natural only by the fact that no water from the upper plain drains into it. Such gullies may be observed at the present day along the banks of any stream whose banks are of soft, loose earth, up and down which persons are accustomed to pass frequently. They are not uncommon where prehistoric village-sites were located on a bank with a tolerably steep slope; but, as stated, their origin is overlooked.

The nearest approach to a “graded way” that is to be found in the Scioto Valley, is a ravine of this kind just north of the circle at High Banks. The river bluff, about sixty feet high at this point, is so steep as to be very difficult of ascent. A pathway was made by the inmates or builders of the circle, in order to reach the water. This is now a large gully. In the loose sand and gravel forming the bluff, rains would rapidly erode the sides and bottom of such a path, and in a comparatively short time cut it down to an easy slope.

Passageways similar to this could be cited, but no other is so large.

The works occupy the high, sandy plain, at the junction of the Muskingum and Ohio rivers. This plain is from eighty to one hundred feet above the bed of the river, and from forty to sixty above the bottom lands of the Muskingum. Its outlines are shown on the map. It is about three fourths of a mile long, by half a mile in width; is bounded on the side next the hills by ravines, formed by streams, and terminates on the side next the river in an abrupt bank, resting upon the recent alluvions. The topography of the plain and adjacent country is minutely represented on this map.

The works consist of two irregular squares, (one containing forty acres area, the other about twenty acres,) in connection with a graded or covered way and sundry mounds and truncated pyramids, the relative positions of which are shown in the plan. The town of Marietta is laid out over them; and, in the progress of improvement, the walls have been considerably reduced and otherwise much obliterated; yet the outlines of the entire works may still be traced. The walls of the principal square, where they remain undisturbed, are now between five and six feet high by twenty or thirty feet base; those of the smaller enclosure are somewhat less. The entrances or gateways at the sides of the latter are each covered by a small mound placed interior to the embankment; at the corners the gateways are in line with it. The larger work is destitute of this feature, unless we class as such an interior crescent wall covering the entrance at its southern angle.

Within the larger enclosure are four elevated squares or truncated pyramids of earth, which, from their resemblance to similar erections in Mexico and Central America, merit a particular notice.59 Three of these have graded passages or avenues of ascent to their tops. The principal one is marked A in the plan, and an engraving more clearly illustrating its features is herewith presented, Fig. 17. It is one hundred and eighty-eight feet long by one hundred and thirty-two wide, and ten high. Midway upon each of its sides are graded ascents, rendering easy the passage to its top. These grades are twenty-five feet wide and sixty feet long. The next in size is marked B in the plan, and is one hundred and fifty feet long by one hundred and twenty wide, and eight feet high. It has three graded passages to its top, viz. upon the north, west, and east. Those at the sides are placed somewhat to the north of the centre of the elevation. Upon the south side there is a recess or hollow way, instead of a glacis, fifty feet long by twenty wide. This elevation is placed upon an easy swell or ridge of land, and occupies the most conspicuous position within the enclosure, every part of which is commanded from its summit. A few feet distant from the northern glacis, is a small conical mound, surrounded with shallow excavations, from which the earth for its construction, and, perhaps, for the construction in part of the pyramidal structure, was taken. To the right of the elevation, and near the eastern angle of the enclosure, is a smaller elevation one hundred and twenty feet long, fifty broad, and six feet high. It had graded ascents at its ends, similar in all respects to those just described. It is now much obliterated. Near the northern angle of the work is another elevation, not distinctly marked. The two larger squares are covered with a close turf, and still preserve their symmetry. Indeed, no erections of earth alone could surpass them in regularity. They are perfectly level on the top, except where some uprooted tree has displaced the earth.

*The Ancient Ohio Trail

THE SACRA VIA

Old maps show (left) the Sacra Via as a long, broad ramp with high earthen walls on both sides, leading up from the Muskingum River to Marietta’s large rectangular enclosure. Its monumental scale survives today as a park, a hundred and fifty feet wide. Such grand “graded ways” were often part of Ohio earthwork complexes.

The ramp was carefully engineered: its width crested in the center like a modern highway, its twenty-foot-high walls were lined with clay. This grand thoroughfare would have weathered floods well, and certainly would have impressed visitors arriving at the earthworks by boat. Its central axis is aligned with the winter solstice sunset; a mound probably marked the spot on the cliff top across the river.