Michmash

In the Old Testament there is a city that still exist today known today as Mikhmas and known in the Old Testament as Michmash. In the Old Testament the pronunciation of Michmash is very similar to the name of the Micmac tribe. Based on their similar beliefs and their Book of Prayers characters, Micmac tribe most likely are direct descendants of the Nephites/Hopewell Indians and survived the Nephite genocide by escaping to the North Alma 22:33. Their geographical location above the hill Cumorah and other factors such as a nomadic lifestyle, being decimated by sickness, as well as wars with the Iroquois (Lamanites), offers more evidence to support this conclusion. Based on the Iroquois beliefs and traditions, the Iroquois are the best candidate to be primarily responsible for the extinction of the Nephites. Michmash in Hebrew means “something hidden”. During the Nephite genocide any surviving Nephites would have to join the Lamanites or hide.

1 Samuel 13:2 “Saul chose him three thousand men of Israel; whereof two thousand were with Saul in Michmash and in mount Beth-el, and a thousand were with Jonathan in Gibeah of Benjamin: and the rest of the people he sent every man to his tent.”

Nehemiah 11 Isaiah 10:28

Reformed Egyptian Four Surviving Characters

In 1680 Father Chretian Le Clercq a Roman Catholic missionary lived among the Micmac Indians for twelve years. After spending this time with the Micmac, he then sailed back to France and wrote a book about the customs and religion of the Micmac Indians.

He helped the Micmac Indians develop a written language composed of Hieroglyphs some of which are Egyptian hieroglyphs. In doing this he most likely used the characters that the Micmac Indians were already familiar with. When he first arrived he saw the Mic Mac Indians writing on birch bark. Four of the Egyptian hieroglyphs are same appearance and meaning as in the Egyptian written language.

If Clercq himself had developed the characters for their written language he most likely would have used the Latin alphabet. The question becomes why would he use Egyptian hieroglyphs but most importantly how did he know the meaning of the hieroglyphs that he used. Egyptian hieroglyphs were undecipherable until 1820 when the Rosetta stone was discovered and allowed for the understanding of the ancient Egyptian written language. The chances of four characters being a coincidence has to be mathematically impossible. The hieroglyphs have to be from the characters the Mi’kmaq Indians were writing on birch bark.

Nephi describes their written language as reformed Egyptian. The majority of Micmac characters are probably reformed Egyptian if not all of them.

The Anthon Transcript is the piece of paper on which Joseph Smith transcribed characters from the golden plates so that Martin Harris could show Dr. Charles Anton. Anton was an Egyptologist who could confirm the validity of the golden plates translation. Per the history, Anton described the characters as Egyptian, Chaldean and Assyrian. Wikipedia

The People of the Dawn

The Mi’kmaq live in what many call New England and Canada today, but the truth is, they have lived in this area of the world for many years before European colonists arrived. L’nu is the word in the Mi’kmaq language for “the people,” and this is how they referred to themselves. When they first met European fur trappers and missionaries, they greeted them with Mi’kmaq, which is the word for “friends.” The colonists took this word to be the name of the people and the term stuck even into the present day. Many Mi’kmaq refer to the area where they live as Dawnland because it sees the dawn before the rest of the country each day. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/8e6d11d6a05a444dbd6c35400b9584f1

About Mi’kmaq Tribe Genealogy

Members of the Mi’kmaq Tribe are the descendants of the L’nuk (the people) of the Mi’kmaq Tribe (our kin relations) born in Mi’kma’ki (the land of our people) speakers of Mi’kmaw (our official language) in Mi’kma’kik (the territory of our people).

Mi’kma’kik, Turtle Island includes many villages located in seven territories called Kespukwitk, Sikepne’katik, Eski’kewaq, Unama’kik, Piktuk aqq Epekwitk, Sikniktewaq, and Kespe’kewaq. Turtle Island includes North America, South America, and the Antarctic. Mi’kma’kik today includes Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, the Gaspé Peninsula of Quebec, the north shore of New Brunswick to the Saint John River watershed, eastern Maine, part of Newfoundland, and the islands in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and St. Pierre, Miquelon.

The Mi’kmaq Tribe is governed by the Sante Mawiomi (Grand Council) led by a kji’saqmaw (grand chief), a putus (treaty holder and counselor), and a kji’keptan (grand captain, advisor on political affairs) for each village in the seven territories of Mi’kma’kik, Turtle Island.

A Tribe consists of individuals, families and clans of specific Turtle Island tribal territories that descend from mtDNA and yDNA haplogroups that originate in Turtle Island and shares autosomal DNA. Including other Turtle Island Tribes and admixture DNA from peoples whose DNA is foreign to Turtle Island.

Words and jargon introduced by peoples foreign to Turtle Island such as Indian, Squaw, Country Wife, Indian Blood, and Metis are racist and debasing and yet continue to be used by many academics, government officials, writers, and individuals today as acceptable language. There is no such thing as “Indian Blood”. The people of Turtle Island ancestry are homo sapiens. The blood types of homo sapiens are: A+, A-, B+, B-, O+, O-, AB+ and AB.

Our DNA contains information that has been passed down with minor mutations from our early ancestors who discovered and settled Turtle Island thousands of years ago. YDNA tests a direct male line through father to son and MTDNA tests the direct maternal line through mother to daughter. Although a mother passes her MTDNA to her sons, her sons do not pass on their MTDNA to their sons or daughters. Autosomal DNA tests 22 non-gender specific chromosomes (autosomes) which is inherited from both parents. Autosomal DNA confirms your relationship to each branch of your family (your grandparents) for five generations and beyond, making it possible to confirm one’s relationship to one’s family, clan, and Tribe.

A haplogroup is a genetic population group of people who share a common ancestor on the paternal or the maternal lines. Top-level haplogroups are assigned letters of the alphabet, and deeper refinements (mutations) consist of additional number and letter combinations specific to where the mutation occurred in the genetic history of homo sapiens. DNA haplogroups are associated with specific geographical areas that link us to the group of people who share ancient ancestors.

The geographical area of Turtle Island haplogroups descend from a small group of ancestral haplogroups who separated from the “out of Africa” population to discover Turtle Island thousands of years ago. The ancestral MTDNA haplogroups are A, B, C, D and X. The YDNA ancestral haplogroups are Q and C. People of Turtle Island ancestry say we have been here since “time immemorial”. A point in time so long ago that we have no knowledge or memory of it. Given that the youngest of the ancestral MTDNA haplogroups that discovered Turtle Island, MTDNA haplogroup X separated from haplogroup N about 30,000 years ago confirms the oral tradition “since time immemorial” as true.

The DNA sub-haplogroups that originate in Turtle Island and do not originate outside of Turtle Island are MTDNA haplogroups A2, B2c, C1b, C1c, C1d, D1, C4c, D2a, and D4h3a, and X2a.

The YDNA sub-haplogroups that originate in Turtle Island and do not originate outside of Turtle Island are YDNA haplogroups Q-M3, Q-L54, Q-Z780, Q-MEH2, Q-SA01, Q-M346, Q-P89.1, Q-NWT01, C-M217, C-M130, C-P39), R1 (M173) and R-M207. All of which descend from a single founding population that discovered Turtle Island thousands of years ago.

The Mi’kmaq shared a kinship, social, political and trade relationship with other Turtle Island Tribes and Confederacies for thousands of years. The Mi’kmaq Tribe is the very first Tribe to have contact with foreigners from other continents.

The genealogy and history of the Mi’kmaq Tribe can establish the lineages of our earliest known ancestors of the Mi’kmaq Tribe, family pedigrees, and our kinship relationship to other Turtle Island Tribes and foreign monarchies and traders.

The genealogy and history of the Mi’kmaq Tribe can establish the lineages of our earliest known ancestors of the Mi’kmaq Tribe, family pedigrees, and our kinship relationship to other Turtle Island Tribes and foreign monarchies and traders.

The Membertou, Chegau, Paul, Joe, and Cope, Mi’kmaq families of Mi’kma’kik, Turtle Island, pre-date contact with peoples foreign to Turtle Island. Colonial writer and lawyer, Marc Lescarbot wrote that: “Membertou was already a man of great age, and saw Captain Jacques Cartier in that country in 1534, being already at that time a married man and the father of a family, though even now he does not look more than fifty years old.” Note, the writer of the colonial record, the lawyer to the King of France, refers to Mi’kma’ki, Turtle Island as a country.

The confederation and creation of the government of Canada only occurred 157 years ago, and yet today entire family lines have disappeared from the records; the seizure of children, adoption, and status and non-status Indian Act legislation has influenced the family lines and genealogy of the descendants of the Mi’kmaq people and founding Tribes of Turtle Island.

Records are entered in the notes field of the Mi’kmaq tribal tree. Any information regarding birth, marriage, death, occupation, census, land ownership/title, military service, voting lists, family bibles, ownership of fishing schooners, businesses, wills and estates, photographs, treaties, wampum, oral traditions, petroglyph photographs, archaeological finds, Colonial, European, Canada and Vatican records are crucial to determining and documenting the history of the Mi’kmaq Tribe.

Turtle Island is entered as a place name if a life event occurred in Turtle Island and the Tribal territory is unknown. Once the Tribe of the territory where the life event occurred confirms the territory name the entry of Turtle Island will be updated to the name of the Tribal territory. Canada or the United States is entered as a place name of the colonial governments that are located within the original Turtle Island territories if the life event occurred after the creation of either one of the two colonial governments.

The coloured dots on the tribal tree represent the oldest proven lineages of the Mi’kmaq Tribe. The Mi’kmaq star indicates the individual is of Mi’kmaq ancestry and the Turtle indicates the individual was born in Turtle Island and married into the Mi’kmaq Tribe.

The Mi’kmaq Tribe includes the Mi’kmaq families, clans, and names of the members of the Mi’kmaq tribe prior to and after contact with peoples foreign to Mi’kma’ki, Turtle Island. The tribal tree is not a public resource for private genealogical research. It is a tribal tree that contains the genealogical history and kinship relationships of the tribe created for the members of the Mi’kmaq Tribe. Access to the tribal tree is not provided to any person that is not of Mi’kmaq ancestry or to any government, education institute, public or private organization that is not a member of the Mi’kmaq Tribe.

To request member access to the tribal tree, please provide your direct lineage to your Mi’kmaq ancestor and/or ancestors. Once the information is confirmed it will be added to the tree and you will be provided member access to the tribal tree. Member access to the tribal tree gives you the ability to upload a Mi’kmaq family member photograph and to update the information for your immediate family to contribute to the genealogical history of the Mi’kmaq Tribe.

You can inquire if your Mi’kmaq ancestor is on the tree by providing the name of your Mi’kmaq ancestor and I will confirm if your ancestor’s name is on the tree. If you ancestor’s name is on the tree but you do not know how you descend from your ancestor, then you will need to research your lineage and provide how you descend from your Mi’kmaq ancestor for member access to the tree.

In Turtle Island one’s identity is defined as much by one’s ancestry as by one’s individual achievement, and the question “Who are you?” is answered by a description of your father, your mother, and your tribe. Mi’kmaq Tribe Genealogy

“There is no Indian who does not consider himself infinitely more happy and more powerful than the French.” Chrestien Le Clercq

“The name Mi’kmaq comes from the word «nikmak», which means, «my close relatives ». The correct spelling of their name is Mikmag however the use of Micmac became very popular over the centuries. The Mi’kmaq were called various other names, depending on the language spoken by the Europeans they got into contact with or the place they met: Indian from Cape Sable, Gaspesians or Mi’kmaq from Gaspé, Matueswiskitchinuuk (Maliseet « porcupine Indian »), shonack (Beothuk « bad Indian »), Souriquois (name used by French) and Torrateen (name used by English). However, between themselves, the Mi’kmaq called each other “L’nu’k” which means the people. The Mi’kmaq share many similarities with the Maliseets of New Brunswick and the Abenaki of New England, with the exception being that they were not farmers. Many believe the Mi’kmaq come from Northern Canada only because their language has common characteristics with Cree.

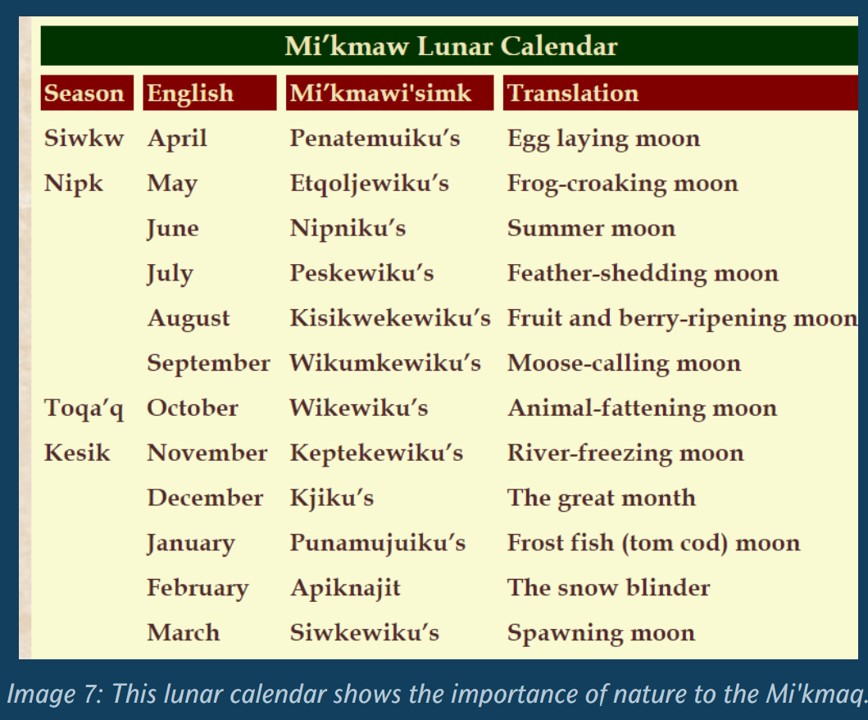

Before the European settlement, the Mi’kmaq lived mainly in Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick and in southern part of Gaspé Peninsula. Nomadic people, hunter-gatherers, they lived in wigwams that were built and taken down in a day, made of spruce, wood, bark, and pine branches, with the inside floors covered in fur for comfort. The big wigwams could shelter ten to twelve people. The wigwams are different from tepees; the latter were made of animal skin and were never used by the Mi’kmaq. To move in the forest or the region’s turbulent rivers, the Mi’kmaq used snowshoes, canoes and toboggans. Their clothes were made out of mammal skin, bird feathers and fish scales to protect them against the winter cold and were also used for ceremonies and rituals. The animal bones and tendons were used to sew together animal skins to make dresses, skirts or coats, etc. The clothes were decorated with things that the Mi’kmaq picked all around. Bones, tendons and animal teeth were also used to make tools as well as stones, roots, tree barks and clay. Men were in charge of making tools whereas women were in charge of making clothes as well as crafts such as baskets.

The Mi’kmaq were the first Indians to come into contact and befriend Europeans. The Vikings and Basque fishermen were distant towards this people, considered primitive because of their different lifestyle and language. John Cabot was the first European explorer who took three Amerindians to England in 1497. The relationship between the Mi’kmaq and the Europeans improved with the dawn of the exploration era undertaken by the Spanish, the Portuguese, the French and the English in their efforts to discover a route to the Orient and its much sought-after spices. The Mi’kmaq traded their fur for European pearls, fabric and firearms. To satisfy an ever-increasing demand for fur, the Mi’kmaq formed an alliance with the Algonquins residing inland, while the European firearms acquired through trade rendered them practically invincible. These two factors largely explain the sudden disappearance of the Iroquois people from the Saint Lawrence River valley, and their replacement, as of 1608, by the Montagnais and other Algonquin-speaking tribes.” http://www.acadian-home.org/Mikmaq-history.html

The American Yawp Reader

A Gaspesian Man Defends His Way of Life, 1641

Chrestien Le Clercq traveled to New France as a missionary, but found that many Native Americans were not interested in adopting European cultural practices. In this document, LeClercq records the words of a Gaspesian man who explained why he believed that his way of life was superior to Le Clercq’s.

… the Indians esteem their camps as much as, and even more than, they do the most superb and commodious of our houses. To this they testified one day to some of our gentlemen of Isle Percée, who, having asked me to serve them as interpreter in a visit which they wished to make to these Indians in order to make the latter understand that it would be very much more advantageous for them to live and to build in our fashion, were extremely surprised when the leading Indian, who had listened with great patience to everything I had said to him on behalf of these gentlemen, answered me in these words :

I am greatly astonished that the French have so little cleverness, as they seem to exhibit in the matter of which thou hast just told me on their behalf, in the effort to persuade us to convert our poles, our barks, and our wigwams into those houses of stone and of wood which are tall and lofty, according to their account, as these trees. Very well! But why now, do men of five to six feet in height need houses which are sixty to eighty? For, in fact, as thou knowest very well thyself, Patriarch—do we not find in our own all the conveniences and the advantages that you have with yours, such as reposing, drinking, sleeping, eating, and amusing ourselves with our friends when we wish? This is not all, my brother, hast thou as much ingenuity and cleverness as the Indians, who carry their houses and their wigwams with them so that they may lodge wheresoever they please, independently of any seignior whatsoever? Thou art not as bold nor as stout as we, because when thou goest on a voyage thou canst not carry upon thy shoulders thy buildings and thy edifices. Therefore it is necessary that thou prepares as many lodgings as thou makest changes of residence, or else thou lodgest in a hired house which does not belong to thee. As for us, we find ourselves secure from all these inconveniences, and we can always say, more truly than thou, that we are at home everywhere, because we set up our wigwams with ease wheresoever we go, and without asking permission of anybody. Thou reproachest us, very inappropriately, that our country is a little hell in contrast with France, which thou comparest to a terrestrial paradise, inasmuch as it yields thee, so thou safest, every kind of provision in abundance.

Thou sayest of us also that we are the most miserable and most unhappy of all men, living without religion, without manners, without honour, without social order, and, in a word, without any rules, like the beasts in our woods and our forests, lacking bread, wine, and a thousand other comforts which thou hast in superfluity in Europe. Well, my brother, if thou dost not yet know the real feelings which our Indians have towards thy country and towards all thy nation, it is proper that I inform thee at once. I beg thee now to believe that, all miserable as we seem in thine eyes, we consider ourselves nevertheless much happier than thou in this, that we are very content with the little that we have; and believe also once for all, I pray, that thou deceivest thyself greatly if thou thinkest to persuade us that thy country is better than ours. For if France, as thou sayest, is a little terrestrial paradise, art thou sensible to leave it? And why abandon wives, children, relatives, and friends? Why risk thy life and thy property every year, and why venture thyself with such risk, in any season whatsoever, to the storms and tempests of the sea in order to come to a strange and barbarous country which thou considerest the poorest and least fortunate of the world? Besides, since we are wholly convinced of the contrary, we scarcely take the trouble to go to France, because we fear, with good reason, lest we find little satisfaction there, seeing, in our own experience, that those who are natives thereof leave it every year in order to enrich themselves on our shores.

We believe, further, that you are also incomparably poorer than we, and that you are only simple journeymen, valets, servants, and slaves, all masters and grand captains though you may appear, seeing that you glory in our old rags and in our miserable suits of beaver which can no longer be of use to us, and that you find among us, in the fishery for cod which you make in these parts, the wherewithal to comfort your misery and the poverty which oppresses you. As to us, we find all our riches and all our conveniences among ourselves, without trouble and without exposing our lives to the dangers in which you find yourselves constantly through your long voyages. And, whilst feeling compassion for you in the sweetness of our repose, we wonder at the anxieties and cares which you give yourselves night and day in order to load your ship. We see also that all your people live, as a rule, only upon cod which you catch among us. It is everlastingly nothing but cod—cod in the morning, cod at midday, cod at evening, and always cod, until things come to such a pass that if you wish some good morsels, it is at our expense; and you are obliged to have recourse to the Indians, whom you despise so much, and to beg them to go a-hunting that you may be regaled.

Now tell me this one little thing, if thou hast any sense: Which of these two is the wisest and happiest—he who labours without ceasing and only obtains, and that with great trouble, enough to live on, or he who rests in comfort and finds all that he needs in the pleasure of hunting and fishing? It is true, that we have not always had the use of bread and of wine which your France produces; but, in fact, before the arrival of the French in these parts, did not the Gaspesians live much longer than now? And if we have not any longer among us any of those old men of a hundred and thirty to forty years, it is only because we are gradually adopting your manner of living, for experience is making it very plain that those of us live longest who, despising your bread, your wine, and your brandy, are content with their natural food of beaver, of moose, of waterfowl, and fish, in accord with the custom of our ancestors and of all the Gaspesian nation. Learn now, my brother, once for all, because I must open to thee my heart: there is no Indian who does not consider himself infinitely more happy and more powerful than the French.

Crestien Le Clercq, New Relation of Gaspesia: With the Customs and Religion of the Gaspesian Indians, William F. Ganong, ed. and trans. (Toronto: 1910), 103-106. http://www.americanyawp.com/reader/colliding-cultures/a-gaspesian-indian-defends-his-way-of-life-1641/

Mi’kmaq Nephites and Christ visit. It is becoming clear that the Mi’kmaq may be remnants of the Nephite nation for several reasons.

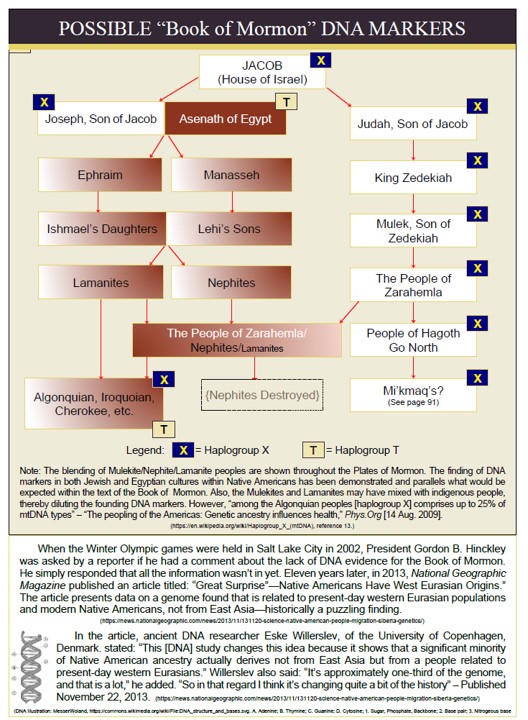

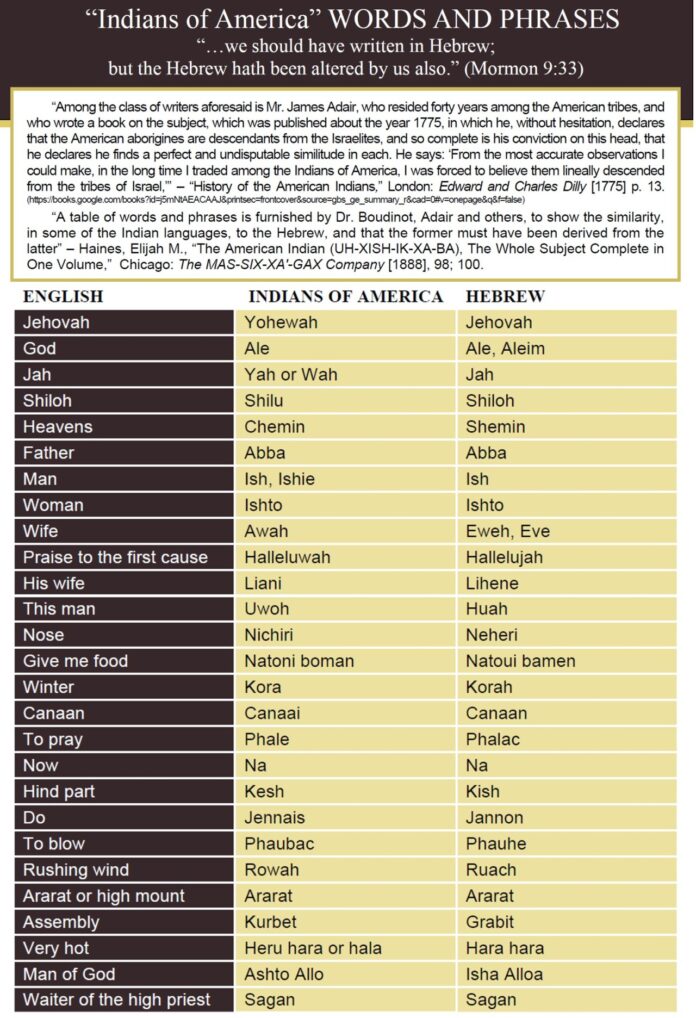

They have four reformed Egyptian characters in their book of Prayers. They have the most examples of Hebrew culture. Comparatively they have high concentrations of Middle Eastern dna. Their geographical location north of the Hill Cumorah also matches well. They are traditional enemies of the Iroquois’ (Lamanite) nation. They have an account of Christ visit.

“Chrestien Le Clercq, O.M.R., (born 1641) was a Recollect Franciscan friar and missionary to the Mi’kmaq on the Gaspé peninsula of Canada in the mid-17th century. He was a chronicler of New France, who wrote two early histories, and translator of a Native American language of that region, adapting an apparently indigenous mnemonic glyph system into a writing system known as Míkmaq hieroglyphic writing.” Wikipedia

In 1680 Father Chretian Le Clercq a Roman Catholic missionary lived among the Micmac Indians for twelve years. Father Clercq was surprised by the many Hebrew customs that the Mi’kmaq had when he asked them if Christians missionaries had taught them these beliefs. The Mi’kmaq elders said that he was the first missionary to visit their tribe.

Examples of Mi’kmaq Hebrew Customs and Beliefs that Father Clercq found among the Mi’kmaq

Hebrew custom of one year betrothal and dowry

Hebrew custom of one year betrothal and dowry

(New Relations of Gaspesia pg 85 )

Belief of a great flood

(New Relations of Gaspesia pg 84 )

Belief they descended from one man and one woman and genesis account

(New Relations of Gaspesia pg 84 )

Their language compared to Hebrew by Silas T Rand

(Legends of the Mic Macs pg 35)

Mi’kmaq Book of Mormon Examples

Belief they sailed to North America as did Lehi and his family (New Relations of Gaspesia pg 84 )

Belief they had letters and a written language

(New Relations of Gaspesia pg 86 )

Christ’s Visit

The Mi’kmaq are visited by a man who performs miracles and people are healed.

The Mi’kmaq are visited by a man who performs miracles and people are healed.

In the Book of Mormon Christ visits the Nephites and performs miracles and healings (New Relations of Gaspesia pg 172 )

This man takes the time to teach the Mi’kmaq people. Christ spends several days if not weeks teaching the Nephites and Lamanites.

(New Relations of Gaspesia pg 172 )

Before a visit by this man the Mi’kmaq’s were under extreme destitution and devastation. Before Christ visit in the Book of Mormon there were natural calamities that devastated the Nephites and Lamanites

(New Relations of Gaspesia pg 172 )

Before Christ visit there was three days of darkness. The Mi’kmaq elders during the devastation of their nation were under a deep sleep consistent with the Book of Mormon. (New Relations of Gaspesia pg 86 )

The Mi’kmaq believe they need to have signs and and tokens in the after life. Father Clercq also believed that they once had the gospel but was lost to due to the licentiousness of their ancestors. “these people had received in times past a knowledge of the Gospel and of Christianity, which they have finally lost through the negligence and the licentiousness of their ancestors” (New Relations of Gaspesia pg 86 )

https://archive.org/details/newrelationofgas05lecl/page/90

https://archive.org/details/cihm_12305/page/n9/mode/2up

Charts from the Annotated Book of Mormon

Purchase Here

Page 542

Page 542