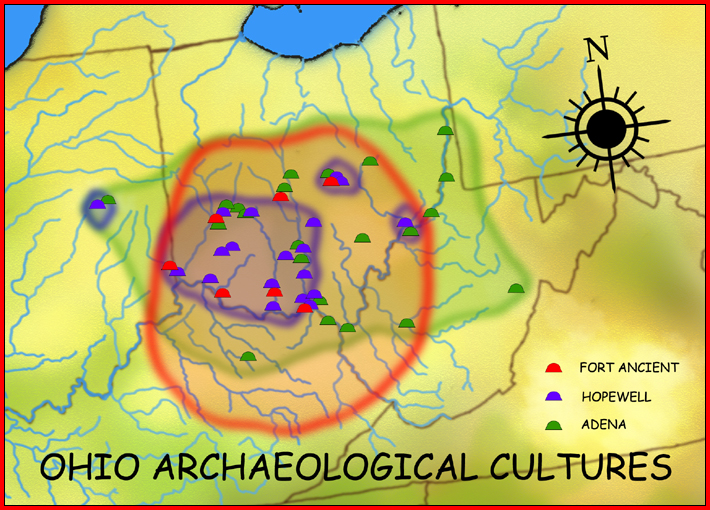

The incredible Hopewell Culture was contemporaneous with the end of the Adena culture, but the Adena people tended to be considerably larger than the Hopewell. Remains of men seven feet tall were common among the Adena, while Hopewell were robust, their males averaged closer to six feet in height. There are four types of earthworks that were constructed by the ancient Hopewell civilization.

- Defensive Enclosure Mounds

- Burial Mounds

- Effigy (Shaped) Mounds

- Ceremonial and Temple Mounds

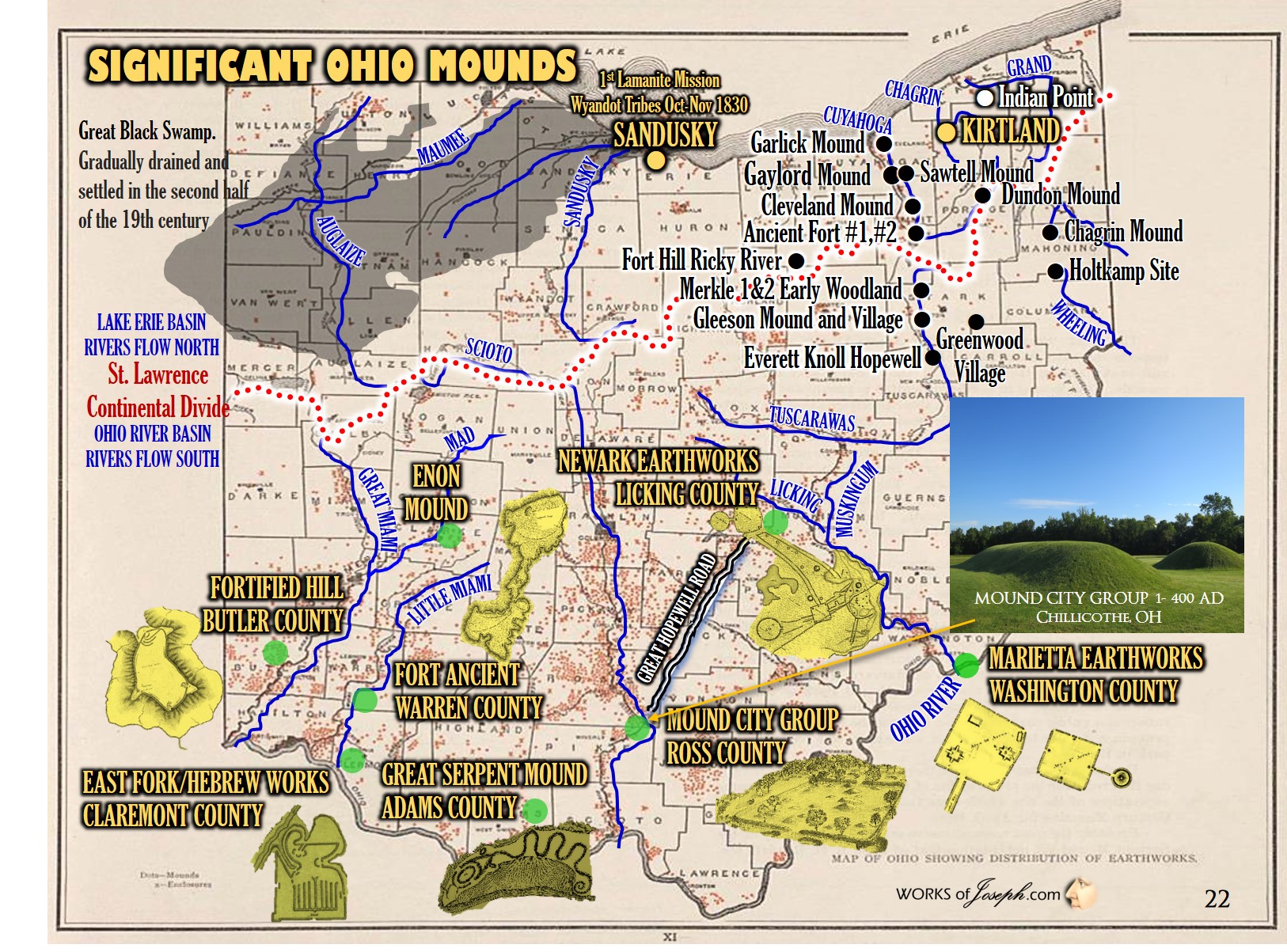

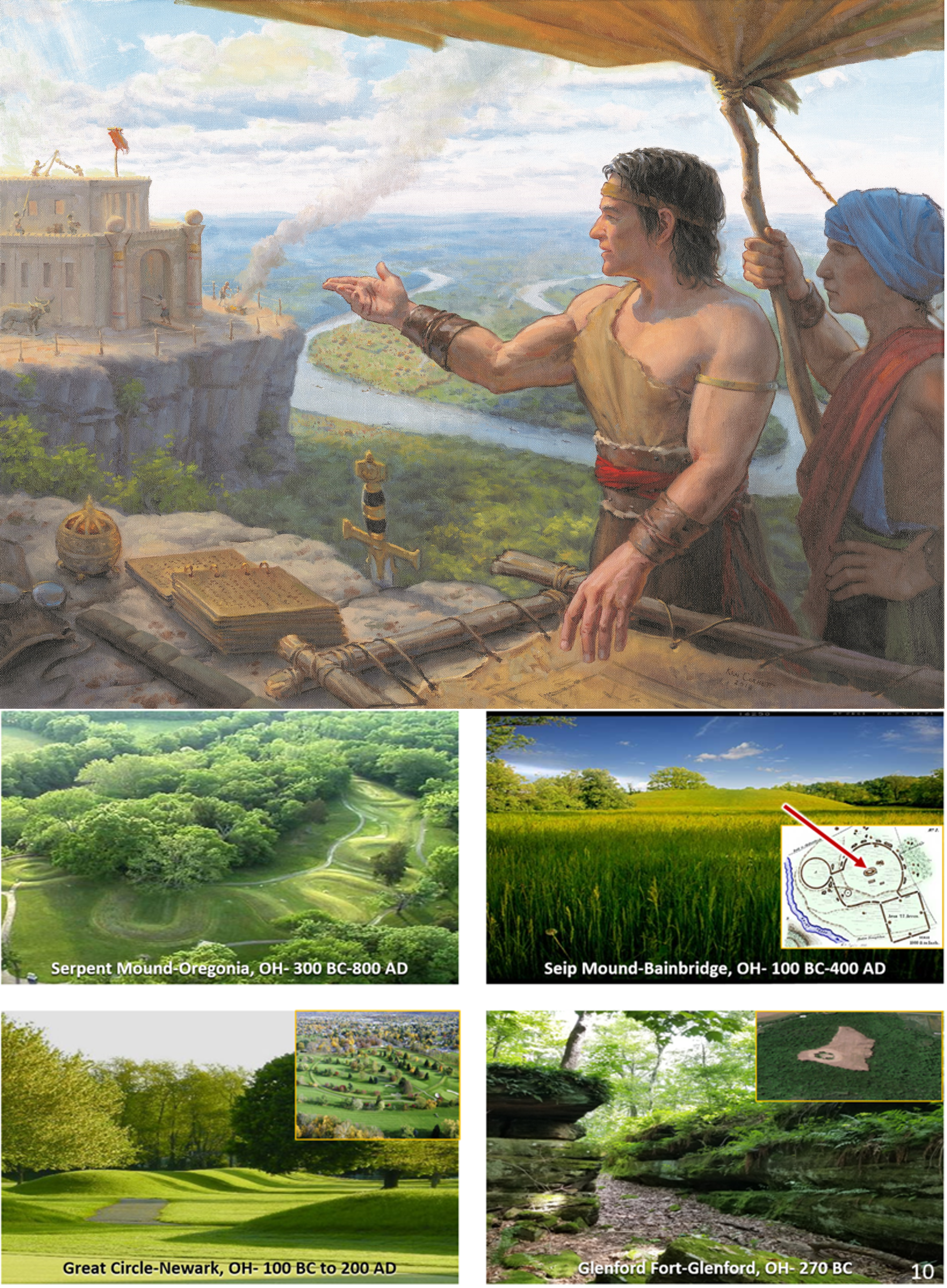

“Mounds were used chiefly as burial places but also as elevated foundations for special structures such as temples (Marietta, OH), hill top enclosures (Fort Ancient, OH), as totemic representations (Serpent Mound in Ohio), and ceremonial space and structures, (The great Circle/Octagon complex, Newark, OH). In size they vary from less than one acre in area to more than 100 acres. Over 200,000 earthworks dotted America’s Heartland.” The Book of Mormon in America’s Heartland page 102 by Rodney Meldrum

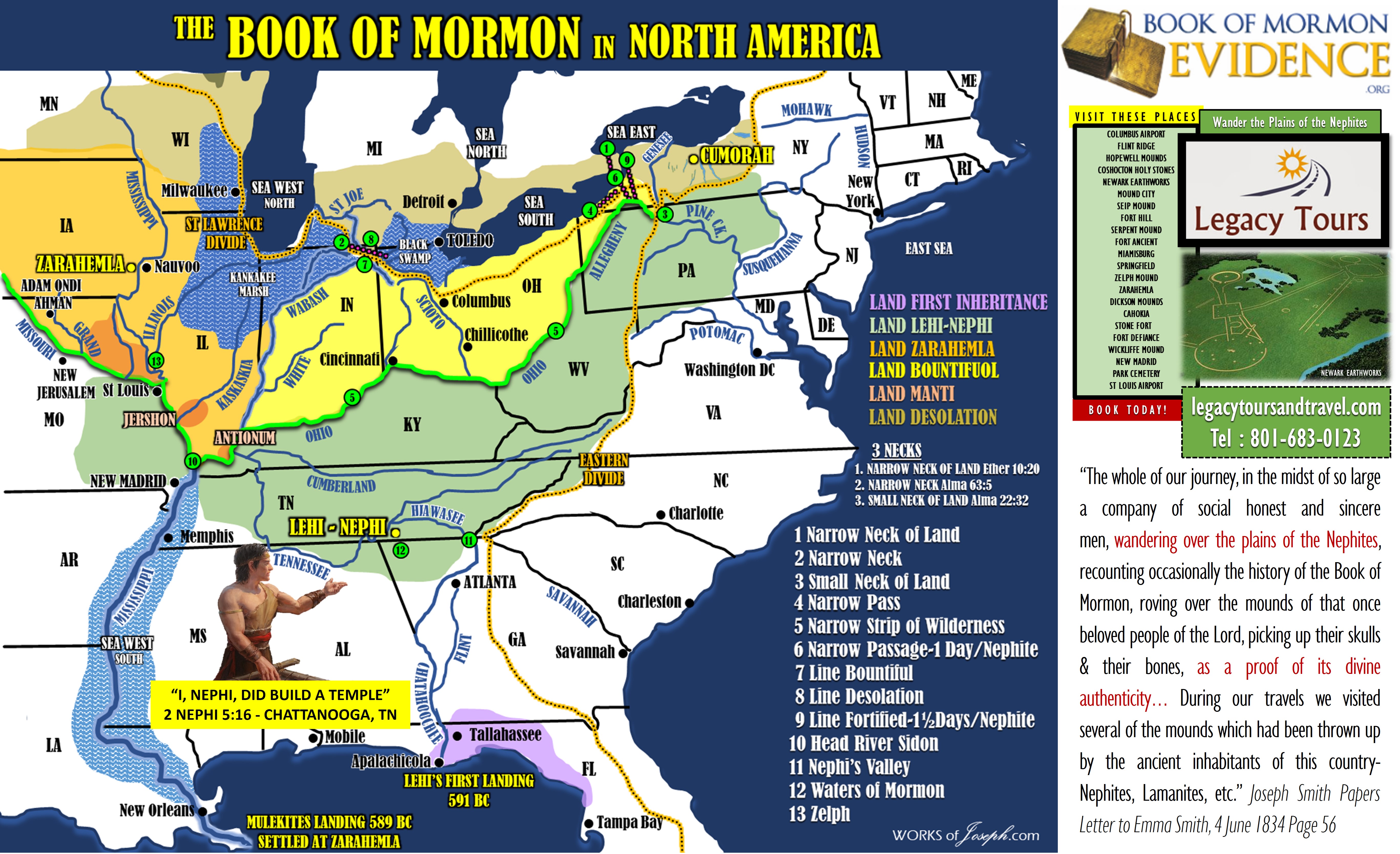

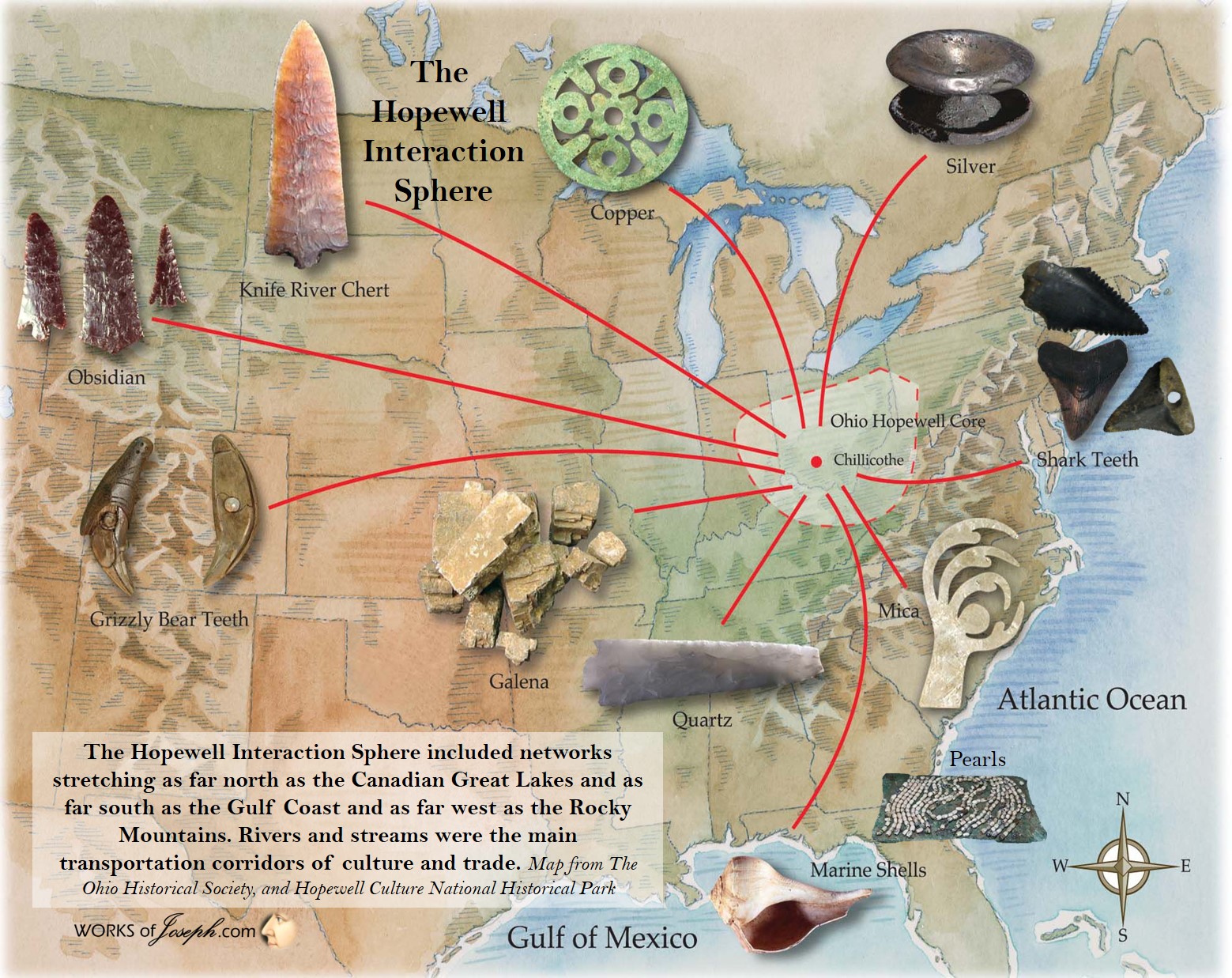

Important Similarities The Hopewell Culture describes the common aspects of the Native American culture that flourished along rivers in the northeastern and midwestern United States from 300 BC to 400 AD, in the Middle Woodland period. The Hopewell tradition was not a single culture or society, but a widely dispersed set of related populations. They were connected by a network of trade routes, known as the Hopewell Exchange System.

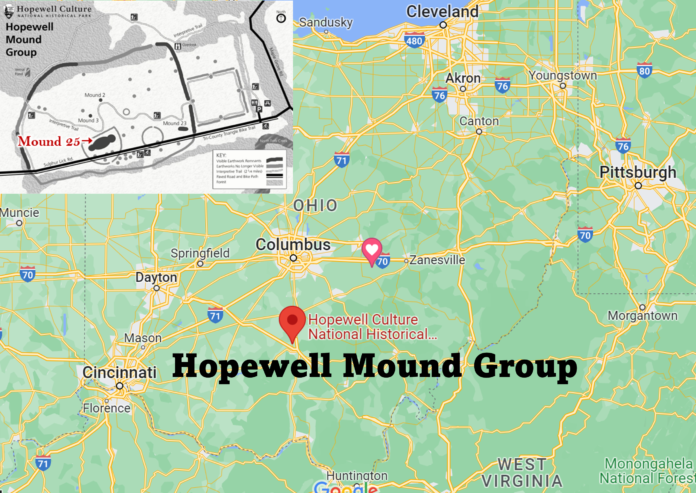

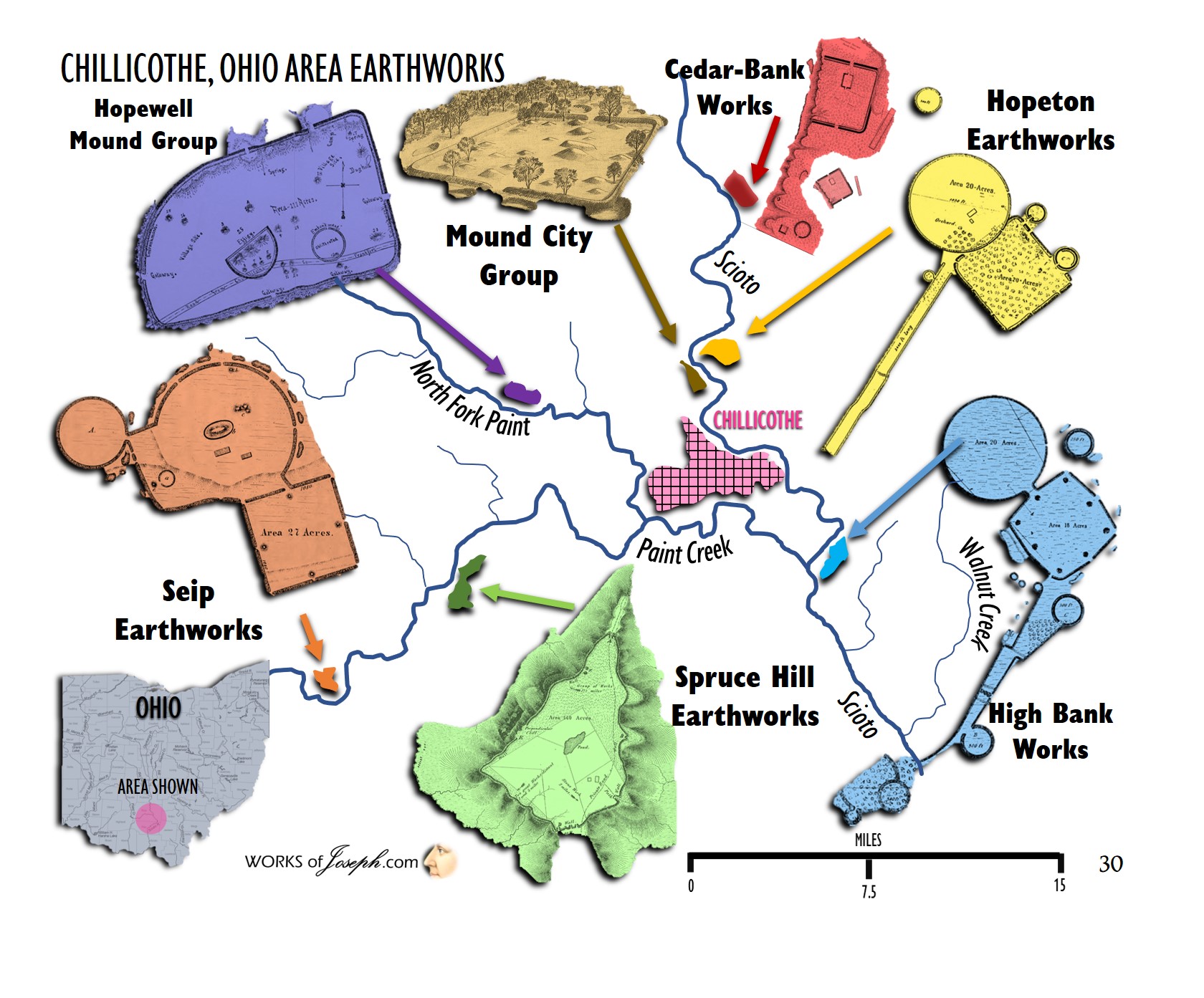

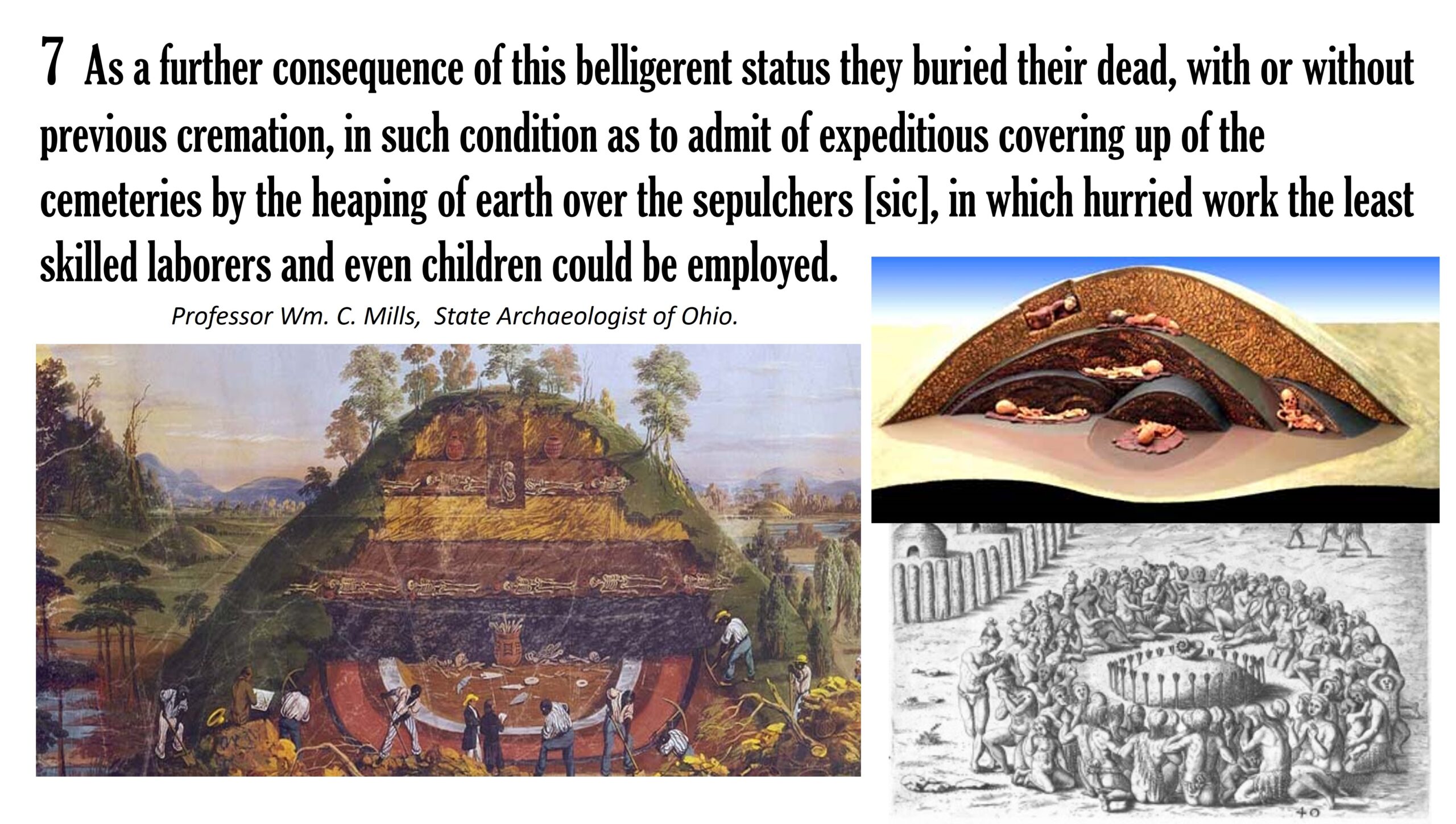

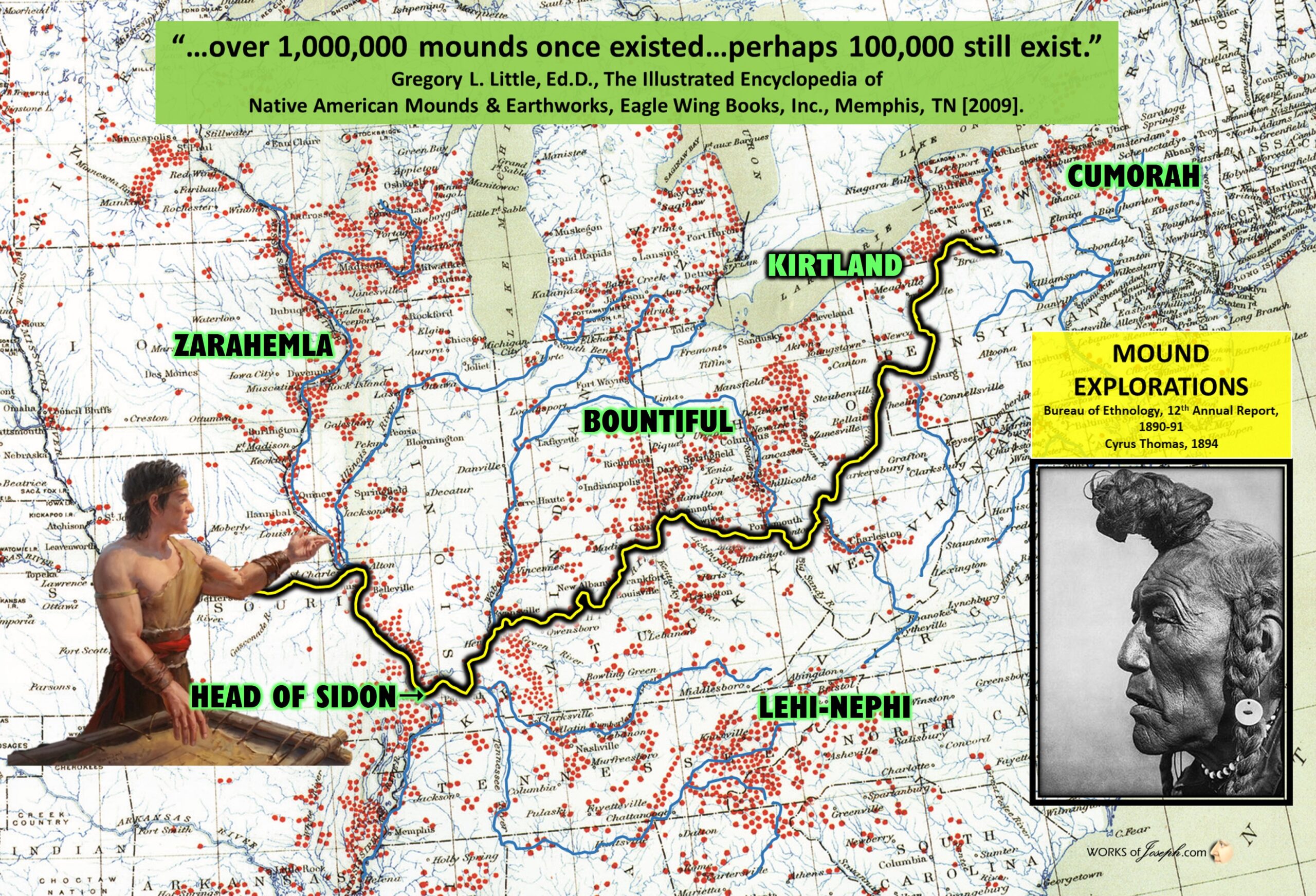

At its greatest extent, the Hopewell Exchange System ran from the Southeastern United States as far south as the Crystal River Indian Mounds into the southeastern Canadian shores of Lake Ontario up north. Within this area societies participated in a high degree of exchange with the highest amount of activity along waterways. The Hopewell Exchange System included copper from the Great Lakes, mica from the Carolinas, obsidian from the Rocky Mountains, and shells from the Gulf Coast. These people then converted the materials into products and exported them through local and regional exchange networks. Although the origins of the Hopewell are still under discussion, the Hopewell culture can also be considered a cultural climax, ending suddenly in about 400 AD. Hopewell populations originated in western New York and moved south into Ohio where they built on top of the local Adena mortuary tradition. Hopewell was also said to have originated in western Illinois and spread by diffusion … to southern Ohio. Similarly, the Havana Hopewell tradition was thought to have spread up the Illinois River and into southwestern Michigan, spawning Goodall Hopewell. The name “Hopewell” was applied by Warren K. Moorehead after his explorations of the Hopewell Mound Group in Ross County, Ohio in 1891 and 1892. The mound group itself was named for the family that owned the earthworks at the time.

The Hopewell location in the Mississippi Valley, plains of Illinois, and Indiana and locations in Ohio match up with the location of the Nephites in the Book of Mormon. The time period also shows a great correlation, especially as both the Hopewell and Nephite civilization abruptly ended in about 400 AD. Rod Meldrum Exploring the Book of Mormon in America’s Heartland.[Out of Print Check Ebay]

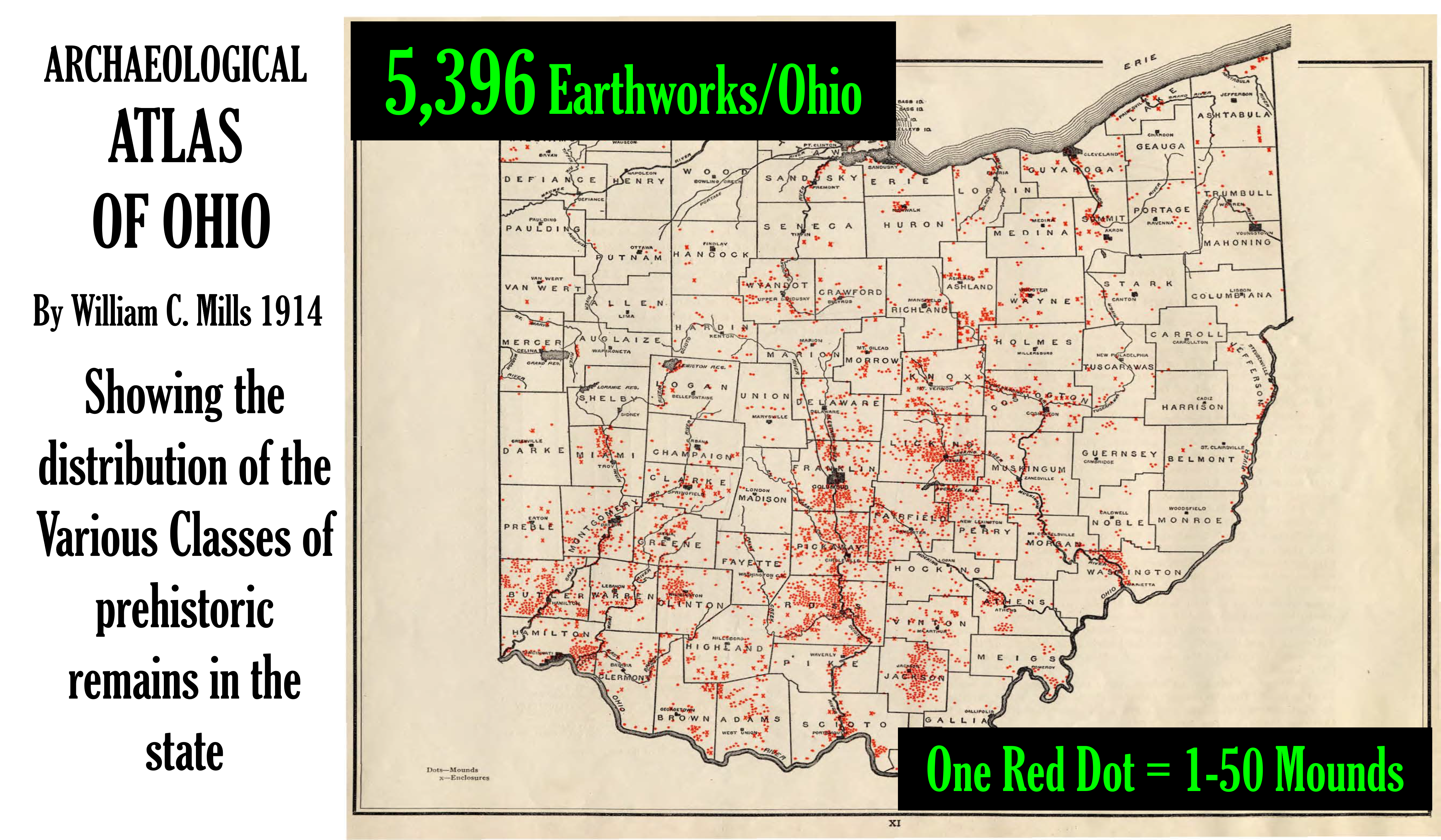

Thousands of United States Ancient Earthworks

(Picture Right) A list of earthworks was compiled to aid in the construction of archaeological maps for the general report and was then published in 1891 as Bulletin 12 of the Bureau of American Ethnology, “Catalogue of Prehistoric Works East of the Rocky Mountains” by Cyrus Thomas. This list, along with information from additional fieldwork, formed the basis for the construction of this map.

There is a temple mound situated above the Ohio River near Cincinnati. “Fragments of burnt limestone may still be seen on the top. The mound is a rectangle two hundred and twenty-five feet long by one hundred and twenty feet broad, and seven feet high.” In contrast to the hewn stone buildings and altars of Mexico, the Ohio mound has the right dimensions to have accommodated a timber and burnt lime plaster (“cement”) building of the size and proportions of Solomon’s Temple.” J. P. Maclean, The Mound Builders – Archaeology of Butler County, Ohio, 1904, pp. 222-223. “Few realize that some of the oldest, largest and most complex structures of ancient archaeology were built of earth, clay, and stone right here in America, in the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. From 6,000 years ago until quite recently, North America was home to some of the most highly advanced and well organized civilizations in the world – complete with cities, roads, and commerce.” Dr. Roger Kennedy, former director of the Smithsonian’s American History Museum.

The Amazing Mound Builders of North America

This is a long and extensive article and blog that you will enjoy. The amount of information contained will give you so much history of the Mound Builders and the thousands off artifacts they have left behind. In my strong opinion, the Hopewell Culture was indeed the Nephite culture of the Book of Mormon. I have broken up the article at times with notes and the following brackets; [ ]. I have included links to relevant blogs as well. If someone wants to connect the Ancient Hopewell Mounds with the Nephites of the Book of Mormon, there is substantial evidence in this article. The United States of America according to Historians ais filled with ancient mounds of the Hopewell, Adena, and Clovis periods of History. I call them the Nephites, the Jaredites and the Adamites.

How Many Mounds?

“The most common question that is asked about mounds is, “How many exist?” In the 1800’s the Smithsonian sponsored many expeditions to identify mound sites across America. A map (shown below) was produced by Cyrus Thomas in 1894 in a Bureau of Ethnology book. They found approximately 100,000 mound sites, many with complexes containing 2 to 100 mounds.

The figure of 100,000 mounds once existing— based on Cyrus Thomas map revealing 100,000 sites—is often cited by others, but that estimate is far, far too low. After visiting several thousand mounds and reviewing the literature, I am fairly certain that over 1,000,000 mounds once existed and that perhaps 100,000 still exist. Oddly, some new mound sites are discovered each year by archaeological surveys in remote areas. But in truth, a large majority of America’s mounds have been completely destroyed by farming, construction, looting, and deliberate total excavations” – Gregory L. Little, Ed.D., The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Native American Mounds & Earthworks, Eagle Wing Books, Inc., Memphis, TN [2009].

Archeological History of Ohio: The Mound Builders and Later Indians

By Gerard Fowke

SOME ANALOGIES BETWEEN THE REMAINS OF MOUND BUILDERS AND THOSE OF MODERN INDIANS.

It is not difficult to understand why so many extravagant theories are zealously proclaimed and readily accepted.

“There is sometimes, it appears to me, an unwillingness to look at all sides of objects classed as ancient, lest something should be discovered which might reduce their age and render them possibly modern and commonplace.” — Mitchell, 18.

“The charm of mystery is so great that men are apt to be carried away with it, and to seek in the development of unknown or improbable causes for the solution of phenomena which are often to be found in plainer and more obvious considerations. That this charm has thrown its spell, to some extent, around the topic of our western antiquities, .cannot be denied.” — Schoolcraft, History, I, 60…

“More recent examination has confirmed an opinion previously formed, that the works described in this publication were erected by a race of men widely different from any type of North American Indians known in modern times.” — Amer., I, 3.

“The ancestors of our North American Indians were mere hunters, while the authors of our tumuli were shepherds and husbandmen.”— Atwater, 213. [Editor’s note: Think similarity with Nephites vs Lamanites]

Of the small stone sculptures made by Indians of the Northwest Coast, “the utmost that can be said is, that they are elaborate, unmeaning carvings, displaying some degree of ingenuity. A much higher rank can be claimed for the mound sculptures; they are faithful copies, not distorted caricatures, from nature. So far as fidelity is concerned, many of them deserve to rank by the side of the best efforts of the artist naturalist of our own day.” — S. & D., 272.

Any “rank can be claimed” for anything. A comparison such as may be made in any of our large museums, of collections from mounds and from the North Pacific Coast Indians, will show the emptiness of this claim. The carvings are not “distorted caricatures ” but faithfully carry out the intentions of the artists, as symbolical and allegorical representations.

“Monuments of a bygone race, of whose history no tradition known to the white man has been preserved by the occupants of the territory.” — Cox: quoted by Foster, 113.

“A broad chasm is to be spanned before we can link the Mound builders to the North American Indians. The latter since known to the white man has spurned the restraints of a sedentary life, which attach to agriculture. He was never known to erect structures which should survive the lapse of a generation. His lodges consist of a few poles over which are stretched barks or skins.” — Foster, 347, condensed.

“The Mound Builders were, in the distinctive character of their structures, as marked a people as the Pelasgi.” [also called Pelasgians, the people who occupied Greece before the 12th century bc. The name was used only by ancient Greeks. (Britannica.com)]— Foster, 97.

“No chief would dare to issue an order to throw up a structure such as that at Cahokia [Apx.1000 AD] or Grave Creek [Apx. 300 BC]; no subaltern would engage in the work. All the free instincts of their nature would revolt.” — Foster, 349, condensed.

After giving an entirely incorrect description of the Indians occupying the eastern half of the United States, Foster says:—

“To suppose that such a race threw up the strong lines of circumvallation and the symmetrical mounds which crown so many of our terraces, is as preposterous, almost, as to suppose that they built the pyramids of Egypt.” — Foster, 300.

“An ancient race, entirely distinct from the Indian, once inhabited the central portion of the United States.” — McLean, 13, condensed…

Under the necessity of catering to a taste for the marvelous and mysterious, newspapers and periodicals, taking their cue from such statements or deductions, rise to heights of fatuity. Almost daily the confiding public is favored with information somewhat after the following fashion:—

Relics Of The Mound Builders.

“Those who are engaged in making collections of ancient relics, will read the following with interest.

“Mr. recently made another highly valuable acquisition to his extensive collection of ancient relics, consisting of the finest specimen of a stone war pipe ever seen in this section of the country. It is in the shape of a small stone ax, and is thoroughly made. The stone is of a beautiful rosewood color and is highly polished. The groove around the ax is perfectly formed, as is also the bowl of the pipe, showing great skill in workmanship. This valuable relic, Mr. informs us, was obtained from Mr. , whose great-grandfather, during the days of

the Revolution, secured it from a noted Indian chief, who had no doubt found it, as the Indians knew nothing about the art of making stone implements, and even if they did know, they did not possess the industry and perseverance to do the work, which must have required great skill, patience and months of toil. This ax was made hundreds of years before the Indians ever set foot upon this country, and was the result of the patient and untiring work of that ancient race of people who built the mounds and earthworks and made the flint arrowheads and spears and all other ancient relics that are so much wondered at and prized by people of the present day.” — Newspaper clipping.

TRADITIONS.

Much stress has been laid upon the total lack of knowledge and absence of tradition on the part of later Ohio Indians concerning the earthworks of the State. Admitting, for the moment, the truth of this argument, so often advanced, it finds a ready and ample explanation.

“Indian tradition is short-lived and evanescent. Except the Creeks, there is scarcely a tribe that has trustworthy tradition of their own annals a century old. The expedition of De Soto is a striking instance of the faint hold tradition had among them. It is hard to imagine anything calculated to make a deeper and more lasting impression on them than the sudden appearance among them of an army of strange beings of different color; [Editor’s Note: Possibly Nephites] bearded, wearing garments and armor of unheard of color and material; mounted on animals that were beyond all experience; armed with thunder and lightning, striding across the continent with a thousand manacled prisoners as slaves, destroying their strongest • towns and laying waste their country, and finally wasting away and driven down the river to the great sea, helpless fugitives. Yet when Europeans next visited the country, a century and a half later, they found not a vestige of a tradition of De Soto.

“Besides, the Indians often changed their place of residence. In their continued warfare, entire tribes were not unfrequently exterminated. Jacques Cartier found the Iroquois at Montreal in 1535. Champlain found them between lakes Ontario and Champlain in 1612. After the destruction of the Eries in 1655, the tract now the State of Ohio was uninhabited until the next century. The nations known as Ohio Indians moved into it after 1700. The Shawnees first appear in history in the region which is now Tennessee and Kentucky, but they had migrated there from elsewhere. The Creeks and Alabama’s arrived in what is now Alabama and Georgia after the expedition of De Soto. Hence, even if they were a people who preserved traditions, they might well be without traditions concerning the mounds found in their hunting grounds.” — Force, 58.

“In the latter half of the seventeenth century, after the destruction of the Eries by the Five Nations, in 1656, what is now the State of Ohio was uninhabited. The Miami Confederacy, inhabiting the southern shore of Lake Michigan, extended southeasterly to the Wabash. The Illinois Confederacy extended down the eastern shore of the Mississippi to within about eighty miles of the Ohio. Hunting parties of the Chickasaws roamed up the eastern shore of the Mississippi to about where Memphis [Memphis; ancient capital of Egypt and is Noph in Phoenician and is Nephi in Hebrew](1), now stands. The Cherokees occupied the slopes and valleys of the mountains about the borders of what is now East Tennessee, North Carolina and Georgia. The great basin, bounded north by Lake Erie, the Miami’s, and the Illinois, west by the Mississippi, east by the Alleghanies, and south by the headwaters of the streams that flow into the Gulf of Mexico, seems to have been uninhabited except by bands of Shawnees and scarcely visited except by war parties of the Five Nations.

“In the next half century, the first half of the eighteenth, various tribes pressed into what is now Ohio, across all its borders. Champlain, in 1609, found on the eastern shore of Lake Huron a tribe called by the Five Nations, Quatoghies, but to which the French gave the name Huron. In some of the earlier relations they are called ‘Hurons or Ouendats.’ Ouendat appears to be the name by which they called themselves. About 1650 the Five Nations nearly destroyed the Hurons or Wendats, and drove the remnant to seek shelter near the western extremity, among the tribes inhabiting the borders of Lake Superior. Afterward, threatened with war by the Sioux, in 1670, they gathered under the protection of the French, about Michilimackinac, and gradually shifted down to Detroit. In the early part of the eighteenth century, under the name of Wyandots (the English spelling of the name which the French spelled Ouendat), a portion of them extended their settlements into the northwestern part of Ohio, and became permanently fixed there.

“The Miamis pushed their borders into the western portion. Shawnees settled the Scioto valley. Delawares moved to the valley of the Muskingum. Little detachments of the Five Nations, mostly Scnecas, occupied part of the northern and eastern borders. The Senecas who settled in the northern part were called by that name. Those who settled in the eastern portion near the Delaware [Indians] and the Pennsylvania border, were called Mingoes. * * * Parties of Cherokees often penetrated north of the Ohio, between 1700 and 1750, and later a party of them settled among the Wyandots [Tribe visited by Oliver Cowdery on Mission to the Lamanites] (2), in the neighborhood of Sandusky. * * * The Eries, so called by the Hurons, were called Rique by the Iroquois, and ‘Nation du Chat’ by the French. * * * In a list of tribes living south of the St. Lawrence and the Lakes, the -Eries are mentioned, and in the [Jesuit] Relation of 1641, they are named as neighbors of the Neutral Nation.”

The French called the Eries “the Cat nation, because there is in their country a prodigious number of wild cats, two or three times as large as our tame cats, but having a beautiful and precious fur, * * * from the skins of which the natives make robes, bordered and ornamented with the tails.” [This probably refers to the lynx, though it may mean the raccoon.] In one of the Jesuit Relations it is stated “This Cat Nation is very populous. * * * It is said they have two thousand men, good warriors, though without fire-arms.”

“In 1654, war broke out between the Eries and the Five Nations.”

Finally the Iroquois invaded the Erie territory. The latter constructed a wooden fort in which they took refuge; but the Iroquois carried it by storm. “With this the Eries disappear. They are afterward mentioned only as a destroyed people. Most of the captives taken by the Iroquois were tortured and burned; but some were adopted and became members of the Five Nations.

“On De Lisle’s map, published in 1720, appears, near the southern shore of Lake Erie, the words, ‘Nation du Chat, detruite.’ On the same map, villages marked ‘Les Tongoria’ are placed on the Ohio, and on the Tennessee rivers. As Colden * * * gives Tongoria as the French equivalent for Erigek, used by the English and Five Nations, Mr. Shea suggests * * * that the Tongorias might be a remnant of the Eries.” — Force, Indians, 3, et seq.

“The Shawnees were not found originally in Ohio, but migrated there after 1750. They were called Chaouanons, by the French, and Shawanoes, by the English. The English name Shawano changed to Shawanee, and recently to Shawnee. * * *

“According to the French accounts, the original seat of the Shawanoes was the southern shore of Lake Erie. In a letter written * * at New Orleans * * * it is said: ‘Besides, the Chaouanons heretofore settled in Canada, * * * are come to settle among the Alibamos.’ The French applied the name Canada to all of the territory held by them, east of the Mississippi, and north of the Ohio.” — Force, Indians, 12-13.

“The tribes occupying Ohio in the period subsequent to 1754 were all intrusive within the period of history. When first known, the Hurons were settled on the southeast of the northern portion of Lake Huron. The Tobacco nation were found in 1616 south of Lake Huron, and just west of the Hurons. Their language was almost identical with the Huron. After their overthrow by the Iroquois, these two tribes wandered over much of the lake country, and many of them finally settled in Ohio. The Iroquois proper, when first known to the French in 1609, did not extend as far west as Lake Erie. The Neutral Nation inhabited the banks of Niagara river, the east end of Lake Erie, and its north shore. They were called Kahkwas by the Senecas. The Jesuit Relation of 1648 says that Lake Erie was formerly inhabited along its south coast by the Cat nation, who had been obliged to draw well inland to avoid their enemies from the west. They had a quantity of fixed villages, for they cultivated the earth, and had the same language as the Hurons. Charlevoix says that the Iroquois obtained from the country of the Eries a fruit which from its description could be only the pawpaw. The plant rarely occurs along the lake and does not fruit there.

“In one instance, the Iroquois (Senecas) overcame 2,000 men of the Cats in their own entrenchments. [See my blog here about the Onondaga (Iroquois) as Joseph Smith’s Indians]

“About 1700, in a war with the Cherokees, the Delawares reached the Ohio, settled, and remained there until 1773. [See blog about Cherokee having Phoenician descents]

“We find, then, that about 1640 the Eries ranged in Ohio from near the east end of Lake Erie to near the west, and held the country back and part of the Ohio river. That everywhere west were Algonquins, probably the Miamis and Ottawas pressing upon them. That below them on the Ohio, were the Shawnees, and southeast of them and their kindred the Andastes were the Algonquin nations.” (3)— Baldwin, 81-90, condensed.

Colden [History of the Five Nations] says the Shawnees, or, as he calls them, the Satanas, formerly lived on the banks of the lakes, and that they were the first people against whom the Five Nations turned their arms after their defeat and expulsion from the region near Montreal by the Adirondacks. There is good reason to believe that this took part in the latter part of the sixteenth century.” — Carr, Mounds, 531, note.

“From all authorities, the two tribes [Eries and Neuters] at least spoke a kindred dialect, namely, a dialect of the Wyandot branch of the Iroquois. It is fair to infer that they were closely affiliated. The remnants of the Eries and Neuters united, but were either completely destroyed or else fled southward. Then the Iroquois attacked the Andastes or Kah-kwas, and drove the survivors of that tribe down the Alleghany. Certainly one of these tribes, perhaps all of them in a body, fled to Carolina and are now known as the Catawbas.” — Schoolcraft, Eries, 290.

“Perrot says that the Iroquois had their original home about Montreal and the Three Rivers, that they fled from the Algonquins to Lake Erie, where lived the Chaouanans, who waged war against them, and drove them to the shores of Lake Ontario. That after many years of war against the Chaouanans and their allies, they withdrew to Carolina, where they now are. The Iroquois, after being obliged to quit Lake Erie, withdrew to Lake Ontario; and that after having chased the Chaouanans and their allies towards Carolina, they have ever since remained there or in the vicinity.”

“Colden says * * * that the French arriving in 1603, found the Adirondacks at war with the Five Nations; that formerly, the Five Nations, then a peaceful tribe, living by agriculture, about the site of Montreal, being oppressed by the Adirondacks, migrated to the southern shore of Lake Ontario, where they at first feebly resisted their pursuers. ‘But afterwards becoming more expert and more used to war, they not only made a brave defense, but likewise made themselves masters of the great lakes, and chased the Shawnees from thence.’ That they increased their numbers by adopting many of the Shawanon prisoners.” — Force, Indians, 14.

“America, when it became known to Europeans, was, as it had long been, a scene of wide-spread revolution. North and south, tribe was given place to tribe, language to language. * * * In Canada and the northern section of the United States, the elements of change were especially active. The Indian population, which, in 1535, Cartier found at Montreal and Quebec, had disappeared at the opening of the next century, and another race had succeeded, in language and customs widely different; while, in the region now forming the State of New York, a power was rising to ferocious vitality, which, but for the presence of Europeans, would probably have subjected, absorbed, or exterminated every other Indian community east of the Mississippi and north of the Ohio.” — Jesuits, xix.

Another example of the little importance to be attached to tradition, or the lack of it, is the statement that at Attaffe there was a “high pillar, round like a pin or needle; it is about forty feet in height, and between two and three feet in diameter at the earth, gradually tapering upward to a point; it is in one piece of pine wood, and arises from the center of a low, circular, artificial hill.” The natives of the town made the same professions of ignorance as to its origin and the same statements as to its antiquity, that they made in regard to mounds in the vicinity.— Bartrams, 455.

While some of the southern pine is extremely durable, it is out of the question to suppose this pole would last more than two hundred and fifty years, the period that had elapsed since De Soto’s expedition when the same tribes were occupying the country that the Bartrams found there.

“The question has often been raised how long a savage tribe, ignorant of writing, is likely to retain the memory of past deeds. From a great many examples in America and elsewhere, it is probable that the lapse of five generations, or say two centuries, completely obliterates all recollection of historic ocurrences. * * * The federation of prominent tribes, and perhaps a genealogy may run back farther.”—Essays, 22.

“The Klallams * * * have no reliable knowledge of their own history earlier than the recollections of the oldest Indian. In obtaining their names for various articles I have often found that persons of eighteen and even twenty-five years of age do not know the names for stone arrow-heads, axes, chisels, anchors, rain-stones and the like, which went out of use soon after the whites came. This shows how quickly the past is forgotten with them.”—Eells: Twana, 609.

Be this as it may, whether their traditions covered two centuries or twenty, it is obvious that the historic Indians of Ohio could know nothing, simply from having lived among them for two or three generations, of remains which they found on their arrival in a deserted country.

Among the Indians outside of the State, however, there were at least two well-defined legends which appear to bear directly upon the prehistoric remains within its boundaries. First, is the tradition of the Lenni Lenape, or, as they are better known, the Delaware’s [Larger nation is called the Algonquin]. This was collected and recorded by Heckewelder as follows:—

Lenape and Mengwe [Lamanites] vs Talligewi [Nephites]

“The Lenni Lenape (according to the traditions handed down to them by their ancestors) resided many hundred years ago, in a very distant country in the western part of the American continent. For some reason, which I do not find accounted for, they determined on migrating to the eastward, and accordingly set out in a body. After a very long journey, and many nights’ encampment by the way (‘Night’s encampment’ is a halt of one year at a place), they at length arrived at the Namaesi Sipu (The Mississippi [River Sidon] or River of Fish; Nomas a Fish; Sipu a River), where they fell in with the Mengwi (The Iroquois or Five Nations), who had likewise emigrated from a distant country, and had struck upon this river somewhat higher up.

Their object was the same with that of the Delawares: they were proceeding on to the eastward, until they should find a country that pleased them. The spies which the Lenape had sent forward for the purpose of reconnoitering, had long before their arrival discovered that the country east of the Mississippi was inhabited by a very powerful nation, who had many large towns built on the great rivers flowing through their land. These people (as I was told) called themselves Talligcu or Talligewi. * * * The Delawares still call the Alleghany Alligewi Sipu the River of the Allegewi. Many wonderful things are told of this famous people. They are said to have been remarkably tall and stout. It is related that they had built themselves regular fortifications or entrenchments, from whence they would sally out, but were generally repulsed. I have seen many of the fortifications said to have been built by them, two of which, in particular, were remarkable. One of them was near the mouth of the river Huron, which empties itself into the Lake St. Clair on the north side of that lake, at the distance of about 20 miles north of Detroit.

The other works, properly entrenchments, being walls or banks of earth regularly thrown up, with a deep ditch on the outside, were on the Huron river, east of the Sandusky, about six or eight miles from Lake Erie. Outside of the gateways of each of these two entrenchments, which lay within a mile of er.ch other, were a number of large flat mounds, in which the Indian pilot said, were buried hundreds of the slain Talligewi, whom I shall hereafter with Colonel Gibson call Allegewi. [We believe the Nephites] When the Lenape arrived on the banks of the Mississippi, they sent a message to the Alligewi to request permission to settle themselves in their neighborhood.

This was refused them, but they obtained leave to pass through the country and seek a settlement farther to the eastward. They accordingly began to cross the Namaesi Sipu, when the Alligewi, seeing that their numbers were so very great, and in fact they consisted of many thousands, made a furious attack on those who had crossed, threatening them all with destruction, if they dared to persist in coming over to their side of the river. Fired at the treachery of these people, and the great loss of men they had sustained, and besides, not being prepared for a conflict, the Lenape consulted on what was to be done.

The Mengwe [Iroquois], who had hitherto been satisfied with being spectators from a distance, offered to join them, on condition that, after conquering the country, they should be entitled to share it with them; their proposal was accepted. Having thus united their forces, the Lenape [Algonquian] and Mengwe [Iroquois] declared war against the Alligewi [Editor’s note. Wayne May and I believe this to be the Nephites], and great battles were fought in which many warriors fell on both sides. The enemy fortified their large towns and erected fortifications, especially on large rivers and near lakes, where they were successively attacked and sometimes stormed by the allies.

An engagement took place in which hundreds fell, who were afterwards buried in holes or laid together in heaps and covered over with earth. No quarter was given, so that the Alligewi, at last finding that their destruction was inevitable if they persisted in their obstinacy, abandoned the country to the conquerors, and fled down the Mississippi river, from whence they never returned. The war which was carried on with this nation, lasted many years, during which the Lenape lost a great number of their warriors. In the end, the conquerors divided the country between themselves; the Mengwe made choice of the lands in the vicinity of the great lakes, and on their tributary streams, and the Lenape took possession of the country to the south. For a long period of time, some say many hundred years, the two nations resided peaceably in this country;—after which the Lenape migrated to the Atlantic coast” — Heckewelder, 47, et seq., condensed.

A translation of Rafinesque, published by Squier, is more literal and goes more minutely into detail.

“The Walum-Olum, (literally painted sticks), or painted and engraved traditions of the Lenni-Lenape, embraces one hundred and eighty-four compound mnemonic symbols, each accompanied by a sentence or verse in the original language, of which a literal translation is given in English by Rafinesque. This translation, so far as I have been able to test it, is a faithful one, and there is slight doubt that the original is what it professes to be, a genuine Indian record. I submitted it, without explanation, to an educated Indian chief, George Copway, who unhesitatingly pronounced it authentic, in respect not only to the original signs and accompanying explanations in the Delaware dialect, but also in the general ideas and conceptions which it embodies. He also bore testimony to the fidelity of the translation.

“The details of the emigrations here recounted, particularly so far as they relate to the passage of the Mississippi and the subsequent contest with the Tallegwi or Allegwi, and the final expulsion of the latter, coincide generally with those given by various authors and well known to have existed among the Delawares. The traditions, in their order, relate first to a migration from the north to the south, attended by a contest with a people denominated Snakes, or Evil, who are driven to the eastward. One of the migrating family, the Lowaniwa, literally northlings, afterwards separate and go to the snow land, whence they subsequently go to the east, towards the island of the retreating Snakes. They cross deep waters and arrive at Shinaki, the Land of’ Firs. Here the Wunkanapi, or Westerners, hesitate, preferring to return.

“A hiatus follows, and the tradition resumes, the tribes still remaining at Shinaki or the Fir Land.

“A hiatus follows, and the tradition resumes, the tribes still remaining at Shinaki or the Fir Land.

“They search for the great and fine island, the land of the Snakes, where they finally arrive, and expel the Snakes. Then they multiply and spread toward the south, to the Akolaki or beautiful land, which is also called Shore-land, and the Big-fir land. Here they tarried long, and for the first time cultivated corn and built towns. In consequence of a great drought, they leave for the Shillilaking or Buffalo land. Here, in consequence of disaffection with their chief, they divide and separate, one party, the Wctamowi, or the Wise, tarrying, the others going off. The Wetamowi build a town on the Wisawana or Yellow River (probably the Missouri), and for a long time are peaceful and happy. War finally breaks out, and a succession of warlike chiefs follows, under whom conquests are made north, east, south and west. In the end Opekasit (literally east-looking) is chief, who, tired with so much warfare, leads his followers towards the sun-rising. They arrive at Messussipu, or Great River (the Mississippi), where, being weary, they stop, and their first chief is Yagawanend or the Hut-maker, under whose chieftancy it is discovered that a strange people, the Tallegwi, possess the rich east land. Some of the Welamowi are slain by the Tallegwi, and then a cry of war! war!! is raised, and they go over and attack the Tallegwi. The contest is continued during the lives of several chiefs, but finally terminates in the Tallegwi being driven southwards. The conquerors then occupy the country on the Ohio below the Great Lakes — the Shawanipekis. To the north are their friends, the Talamatan, literally not-of-themselves, translated Hurons. The Hurons, however, are not always friends, and they have occasional contests with them.

“Another hiatus follows, and the record resumes by saying that they were strong and peaceful at the land of the Tallegwi. They built towns and planted corn. A long succession of chiefs followed, when war again broke out, and finally a portion under Linkewinnek or the Sharp-looking, went eastward beyond the Talega-chukung or Allegheny Mountains. Here they spread widely, warring against the Mengwi or Spring-people, the Pungelika, Lynx or Eries, and the Mohegans, or Wolves. The various tribes into which they became divided, the chiefs of each in their order, with the territories which they occupied, are then named — bringing the record down until the Etrrival of the Europeans. This latter portion we are able to verify in great part from authentic history.

“I have alluded to the general identity of the mythological traditions here recorded, with those which are known to have been, and which are still current among the nations of the Algonquin stock. The same may be observed of the traditions which are of a historical character, and particularly that which relates to the contest with the people denominated the Tallegwi. The name of this people is still perpetuated in the word Alleghany, the original significance of which is more apparent when it is written in an unabbreviated form, Tallegwi-hanna, literally river of the Tallegwi. It was applied to the Ohio, and is still retained as the designation of its northern or principal tributary.

“It will be seen that there is a difference between the traditions, as given by Heckewelder, and the lValum-Olum in respect to the name of the confederates against the Tallegwi. In the latter the allies are called Talamatan literally not-of-themselves, and which, in one or two cases, is translated Hurons with what correctness I am not prepared to say. Heckewelder calls them Mengi, Iroquois. This must be a mistake, as the Mengwi are subsequently and very clearly alluded to in the WalumOlum as distinct from the Talamatan. In Heckewelder we find the Hurons sometimes called Delamattenos, which is probably but another mode of writing Talamatan.” — Squier, Algonquins, 14-41, condensed.

Dr. Brinton thus interprets the legend:—

“Were I to reconstruct their ancient history from the Walum Olum as I understand it, the result would read as follows:— .

“At some remote period their ancestors dwelt far to the northeast, on tide-water, probably at Labrador. They journeyed south and west, till they reached a broad water, full of islands and abounding in fish, perhaps the St. Lawrence about the Thousand Isles. They crossed and dwelt for some generations in the pine and hemlock regions of New York, fighting more or less with the Snake people, and the Talega, agricultural nations, living in stationary villages to the southwest of them, in the area of Ohio and Indiana. They drove out the former, but the latter remained on the upper Ohio and its branches. The Lenape, now settled on the streams in Indiana, wished to remove to the East to join the Mohegans and other of their kin who had moved there directly from New York. They, therefore, united with the Hurons (Talematans) to drive out the Talega [Tsalaki. Cherokees] from the upper Ohio. This they only succeeded in accomplishing finally in the historic period. But they did clear the road and reached the Delaware valley, though neither forgetting nor giving up their claims to their western territory”

Heckewelder’s account, or translation, gives a pronunciation which “reduces our quest to that of a nation who called themselves by a name, which, to Lenape ears, would sound like Tallike. Such a nation presents itself at once in’ the Cherokees. who call themselves Tsa’laki. [Cherokee are of Iroquois Stock] Moreover they fill the requirements in other particulars. Their ancient traditions assign them a residence precisely where the Delaware legends locate the Tallike, to-wit, on the upper waters of the Ohio. Fragments of them continued there until within the historic period; and the persistent hostility between them and the Delawares points to some ancient and important contest.

“Name, location and legends, therefore, combine to identify the Cherokees or Tsalika with the Tallike; and this is as much evidence as we can expect to produce in such researches.

“The question remains, whether the Tallike were the ‘Moundbuilders.’ It is not so stated in the Walum-Olum. The inference rather is that the ‘Snake people’ dwelt in the river valleys north of the Ohio River in the area of Western Ohio and Indiana, where the most important earthworks are found — and singularly enough none more remarkable than the [Serpent Mound.] According to the Red Score, the Snake people were conquered by the Algonkins long before the contest with the Taillike began. These latter lay between the position then occupied by the Lenape and the eastern territory where they were found by the whites. In other words, the Taillike were on the upper Ohio and its tributaries, and they had to be driven south before the path across the mountains was open.” — Brinton, Lenape, 165 and 230-1.

Schoolcraft ridicules the Lenape tradition; says a request for permission to pass through the country is entirely foreign to the Indian manner of doing things; and that the whole tradition is simply a local rendering of the 20th chapter of Numbers, where the Jewish leader demands a passport through the land of Edom.—Schoolcraft, Iroquois, 315.

The second tradition is one reduced to writing by Cusick, an Iroquois chief, and printed by Beauchamp.

“About this time the northern nations formed a confederacy and seated a great council fire on river St. Lawrence; the northern nations possessed the bank of the great lakes; the countries in the north were plenty of beaver, but the hunters were often opposed by the big snakes. The people live on the south side of the Big Lakes make bread of roots and obtain a kind of potatoes and beans found on the rich soil.

“Perhaps about two thousand two hundred years before Columbus discovered the America and northern nations appointed a prince, and immediately repaired to the south and visited the great Emperor who resided at the Golden City [Possibly St Louis, MO], a capital of the vast empire. After a time the Emperor built many forts throughout his dominions and almost penetrated the Lake Erie; this produced an excitement, the people of the north felt that they would soon be deprived of the country on the south side of the Great Lakes they determined to defend their country against any infringement of foreign people; long bloody wars ensued which perhaps lasted about one hundred years; the people of the north were too skillful in the use of bows and arrows and could endure hardships which proved fatal to a foreign people; at last the northern nations gained the conquest and all the towns and forts were totally destroyed and left them in a heap of ruins.” — Cusick, 10.

“Some have thought the Emperor of the Golden City a Mexican .monarch, and that the Mound-builders of the Ohio and Mississippi valleys were his subjects.” — Beauchamp, 10.

[Editors Note: In about 900 AD the Mayan civilization ended and it seems they migrated up the Mississippi and conquered the Lamanites in North America. Later the original Natives pushed the Mayans back to Central America. See my blog here: ]

Hale, probably the most competent authority on languages of eastern Indians, expresses himself as follows on these two traditions:—

In regard to Cusick’s tradition. “There is not the slightest reason for supposing that this narrative is a fabrication. Cusick’s work bears throughout the stamp of perfect sincerity. There is nothing in it drawn from books, or, as far as can be discovered, from any other source than native tradition. Of the Delaware tradition, the purely historical part bias, like Cusick’s narrative, an authentic air. The country from which the Lenape migrated was Shinaki, ‘the land of fir-trees,’ not in the .west, but in the far north — evidently the woody region north of Lake Superior. The people who joined them in the war against the Alleghewi (or Tallegwi, as they are called in this record), were the Talamatan, no doubt the Huron-Iroquois people, as they existed before their separation. That this river [the ‘Messusipu’] was not our Mississippi, is evident from the fact that the works of the Mound-builders extended far to the westward of the latter river, and would have been encountered by the invading nations, if they had approached it from the west, long before they arrived at its banks. The ‘Great River’ was apparently the upper St. Lawrence, and most probably that portion of it which flows from Lake Huron to Lake Erie, and which is commonly known as the Detroit River. There can be no reasonable doubt that the Alleghewi or Tallegwi, who have given their name to the Alleghany River and Mountains, were the Mound-builders. The destiny which ultimately befell the Moundbuilders can be inferred from what was known of the fate of the Hurons themselves in their final war with the Iroquois. The greater portion of the Huron people were exterminated, and their towns reduced to ashes. Of the survivors many were received and adopted among the conquerers. A few fled to the east and sought protection from the French, while a larger remnant retired to the northwest, and took shelter among the friendly Ojibwas. The fate of the Tallegwi was doubtless similar to that which overtook the descendants of their Huron conquerers. Solong as the conflict continued it was a war of extermination. All the conquered were massacred, and all that was perishable in their towns was destroyed. When they finally yielded, many of the captives would be spared to recruit the thinned ranks of their conquerers. Such adoption of defeated enemies is one of the most ancient and cardinal principals of the Huron-Iroquois well-devised political system. It is by no means unlikely that a portion of the Mound Builders may, during the conflict, have separated from the rest, and deliberately united their destiny with those of the conquering race. Either in such an alliance or in the adoption of captive enemies, we may discern the origin of the great Cherokee nation, a people speaking a mixed language which shows evident traces of its mixed origin,—in grammar mainly Huron-Iroquois, and in vocabulary largely recruited from some foreign source. Another portion of the defeated race, fleeing southward, would come directly into the country of the Chahta, or Choctaws. [Muskeogans] With these the northern conquerers would have no quarrel and the remnant of the Alleghewi would be allowed to remain in peace. Every known fact favors the view that during a period which may be estimated at between one and two thousand years ago, the Ohio valley was occupied by an industrious population of some Indian stock, which had attained a grade of civilization similar to that now held by the village Indians of New Mexico and Arizona; that this population was assailed from the north by less civilized and more warlike tribes of Algonkins and Hurons, acting in a temporary league, similar to those alliances which Pontiac and Tecumseh afterwards rallied against the white colonists; that after a long and wasting war the assailants were victorious; the conquered people were in a great part exterminated; the survivors were either incorporated with the conquering tribes or fled southward and found refuge among the nations which possessed the region lying between the Ohio valley and the Gulf of Mexico; and that this mixture of races has largely modified the language, character and usages of the Cherokee and Choctaw nations.”

It may be considered as beyond dispute that the Cherokees are a branch or off-shoot of the Huron-Iroquois family. Their language proves it. “The striking fact has become evident that the course of this migration of the Huron-Cherokee family has been from eastern Canada, on the Lower St. Lawrence, to the mountains of northern Alabama.” — Hale, condensed.

It is rather hazardous to venture a definite opinion regarding the region where the events alluded to in these two legends may have occurred. We can at once, however, discard the Mississippi and Missouri rivers form the problem. The most that can be made of the words resembling the former name is that they denote a river abounding in fish. The term “yellow” would naturally be applied by people accustomed only to clear waters flowing through rocky channels or carrying but little silt, to any stream which remains muddy from one rain to the next.

Heckewelder’s identification of Detroit as the crossing place may not be incorrect, but it is clearly not supported by the presence of remains that can be attributed to the Mound Builders of Southern Ohio. In fact, no evidences of their occupation are to be found near the rivers connecting the Great Lakes; and the country about the western end of Lake Erie is especially lacking in remains of the Mound Builders or of any prehistoric race closely resembling them. It is true that various references may be found to ancient works in this vicinity; but the enclosures remaining all belong to the same class with those of New York and northern Ohio; and the latter, as we have learned, are undoubtedly of Iroquois construction. The “mounds” are usually so like ordinary beach ridges or wind dunes, that, as one explorer put it, “the only way to tell which is natural and which artificial, is to dig into them. If we find human remains, we know it is a mound; if not, we know it is a dune.” It seems to be forgotten these dunes were sought by Indians as sites for residence and burial purposes, and that their shape is continually changing. The wind piles sand on them at one time, and carries it away at another. Articles left on the surface of the ground may thus be covered to a depth of several feet; while others, once deeply buried, may be brought to light. The methods of interment are usually in close accord with those observed in burial places known to belong to the Hurons.

“There are (or have been, for little remains) several tumuli upon and near the bank of the Detroit River, from two to four miles below the city. All are burial mounds. They occupy sandy elevations, fifteen to twenty feet above the water, are conical in shape, five to twenty-five feet in height, and thirty to fifty feet broad. All contain numerous skeletons, both original and intrusive. The former are found on or near the original surface, and are mostly in a sitting posture, and the faces toward the east, and sometimes a dozen or more are found arranged around the center in a circle. In one case, each held in his arms a pot, of unusual size, having a capacity of about two gallons. In other cases, pots are found near the heads. With these skeletons are the usual stone implements. One, and by far the largest of the mounds in the vicinity of Detroit, seems somewhat exceptional in its character. It is situated at the junction of the River Rouge with the Detroit, and was originally probably not less than four hundred feet long by two hundred broad and thirty or forty high. It is built of the light sand of the neighborhood, and contained many hundreds, if not thousands of skeletons, in every stage of decay and burial. It had two or more pits filled with great numbers of bones, promiscuously disposed, and apparently corresponding with those used by the Hurons, and some other tribes at their ‘Festival of the Dead.’ It is hardly possible to dig into the mound at any point, and to any depth from two to ten feet, or even more, without disinterring human bones. Evidences of cremation abound in some parts of the mound, and at various depths. The modes of interment are without uniform system.” — Hubbard, Relics, condensed.

There is such discrepancy in the measurements of the “Great Mound,” that one is in doubt whether to attribute them to guess-work, or to suppose the “light sand” composing it varied in volume at different times. Hubbard’s figures are just given; Gillman tells us that

“With a height of 20 feet, it must originally have measured about 300 feet in length by 200 feet in width.” — Gillman, M. B., 305.

Peet multiplies this several fold; for he says

“The Detroit mound was originally 700 or 800 feet long, 400 feet wide, 40 feet high.” —Peet, Amer. Antiq., July, 1888, 38.

Gillman made some explorations which he thus reports.

“At what was presumed to be its original center, in the River Rouge mound at Detroit, at the depth of three feet human bones were exhumed. At four feet deep occurred abundant evidence of cremation. Then four feet of nothing but sand. Eight feet from the surface were white limelike masses, each of a few inches in circumference, which subsequent examination proved to be human bones. These, in general ball-like masses continued to a depth of ten and one-half feet, where operations were suspended.” — Gillman, Lakes, 327, condensed.

His assertion that “ball-like masses” “a few inches in circumference” were “human bones,” is very improbable. We can not imagine in what manner they could be buried to assume this form or reduced to this limit. If the mound is artificial, even in part, the method of burial reported — granting the supposition of burials — shows its erection to have extended over a long period; and while mounds were thus built up in Virginia by tribes allied to the Iroquois, we find nothing of this particular kind of continuous burial in southern Ohio.

Gillman also reports excavations farther north.

Numerous mounds extend “for about a mile and a half, along the west shore of the [St. Clair] river and of Lake Huron.” They “were largely used for burial purposes.” In one, “a wide area at one end [was] covered with a solid crust of black ashes, from eighteen inches to two feet thick, containing the bones of various animals used for food, broken pottery, and stone implements. The relics from these mounds [included] an extraordinarily large number of broken stone hammers of the rudest kind.” In one “several interments had been made” and some relics were found.—Gillman, M. B., 372.

It is clearly evident that in this case, as in many others, Mr. Gillman was working on the site of an old Indian camping place, on one of the natural sand-dunes so abundant in that region. His “hammers” were the stones which had been used in boiling food. Interments immediately around, or even within, the huts are not uncommon.

*****

On the other hand, if it be assumed that the Allegwi were the Mound Builders; that they met the invaders at either end of Lake Erie; that they were driven from the borders back to the interior; and that, consequently, the last struggle reached its maximum in southern Ohio;—then the progressive development of defensive works will be accounted for. First to be constructed for such purposes, when the great squares and circles and the minor embankments in connection with them became untenable, would be the hill-top enclosures in the same localities. When these no longer sufficed, the original inhabitants, hard pressed on every side, would be driven to the construction of strongholds in rugged, broken country, as exemplified in structures like Fort Hill and the Glenford Fort. This is on the customary hypothesis that all such works are due to the same people who made the valley enclosures If the aggressors followed closely on the rear of the defeated Tallegwi, and themselves constructed the irregular enclosures and hill-top forts, either the same or the reverse order might be taken. There might be first a temporary fortification, like the smaller hill-top enclosures, where they could find shelter until an opportunity for retreat; and afterwards a permanent defensive work like Fort Hill, where they could be safe as long as they chose to remain. Or the stronger forts could be occupied first, and the others constructed when the waning strength of the Tallegwi emboldened their foes to close in on them…

“Emperor” and “Prince,” by both title and office, were as unfamiliar to Iroquois, until they learned of them from whites, as “gold” or “city;” and the same reasons which permit us to substitute chief or sachem for such fanciful titles, give us a right to replace the term “Golden City” by “town where much copper is.”

Besides these two traditions, which must refer to some ancient tribe of Ohio, if not to that known as the Mound Builders, Carr shows that the origin or cause of mounds and enclosures was not unknown to various other tribes. The Cherokees, Senecas, Kaskaskias, Piankeshaws, Muskogees, and others say their forefathers constructed such.—Carr, Mounds, 563, et seq.

“De Soto, in 1540, could get no tradition concerning them [mounds] beyond the assurance that the peoples he encountered had built them or some of them.” — Winsor: History, I, 397.

“The Iroquois believed that the Ohio mounds were the memorial of a war which in ancient times they waged with the Cherokees.” — Essays, 69; from Schoolcraft.

“John Norton, the intelligent Mohawk chief [said] that there was a tradition in his tribe that [mounds and enclosures] were constructed by a people who in ancient times occupied a great extent of the country, but who had been extirpated; that there had been long and bloody wars between this people and the Five Nations, in which the latter had been finally victorious. He added that one of the last fortifications which was taken had been obstinately defended; that the warriors of the other four nations of the confederacy had assaulted it without waiting for the Mohawks, and had been repulsed with great loss, but that the latter coming to their assistance the attack was renewed, the place taken, and all who were in it destroyed.” — Stone, II, 48(5, note.

Norton’s statement refers to the war with the Eries; at least the last battle between these two nations was fought much as he describes it.

“The Wyandots have always assumed to have been originally at the head of the Iroquois group of tribes. * * * In mentioning the name of this tribe to Mr. J. C. Calhoun, of South Carolina, he said that when at college at New Haven in 1802, a Mr. Williams, a respectable and intelligent man, a half Wyandot, and a person interested in the land claims of Connecticut in Ohio, informed him that the old forts in the Ohio valley were erected some 150 or 200 years before, in the course of a long war which was carried on between the Wyandots (this, I think, to tally with other traditions, should be Iroquois) and the Cherokees. In this war the northern confederates finally prevailed.” — Schoolcraft, Iroquois, 162.

*****

The Cherokees are so frequently mentioned in discussing the Mound Builders, as to require further notice.

In 1650 the Cherokees had a tradition which claimed “they came from the west and exterminated the former inhabitants;” and then says they came from the upper parts of the Ohio, where they erected the mounds on Grave Creek, and that they removed hither [i. e., to East Tennessee] from the country where Monticello is situated. They are not noticed by Mr. Jefferson in his table of original tribes which inhabited any part of Virginia at or subsequent to the year 1(506, and from then up to 1669. They say themselves that their nation did not erect the mounds, nor paint the figures of the sun and moon upon the rocks where they are now seen.” “The mounds exhibited the same appearance at the arrival of the Cherokees as they now do.”

“They have a fabulous tradition respecting the mounds which proves that they are beyond the events of their history. The mounds, they say, were caused by the quaking of the earth, and a great noise with it.” — Haywood, 225, 234, and 280.

“The Cherokees themselves are as ignorant as we are, by what people or for what purpose these artificial hills were raised; * * * they have a tradition common with other nations of Indians, that they found them in much the same condition as they now appear, when their forefathers arrived from the west and possessed themselves of the country, after vanquishing the nations of red men who then inhabited it, who themselves found these mounts when they took possession of the country, the former possessors delivering the same story concerning them.”

— Bar-trams, 365.

“From the verbal traditions of Mr. Stand Watie [a Cherokee chief], the Cherokees anciently lived at the Otter Peaks in Virginia,* * * and they were in the habit of crossing the Ohio with their war parties.”

— Schoolcraft, Iroquois, 163.

The Mohican or Stockbridge tribe had a tradition that “many thousand moons ago ” the Cherokees, Nanticokes, and some other tribe whose name they had forgotten, came from the south and attacked the Delawares. The latter were overcome, at first, but the Mohicans came to their relief, and the invaders were driven back. The Nanticokes lived on the eastern shore of Maryland, and it is improbable that the Cherokees -could have been their neighbors at any time, even though their traditions claim the Powhatans as being a branch of their tribe. Certainly they could not have been in Virginia as late as 1623, for De Soto found them located in Georgia.— Royce. 136 and 137.

How Mounds Were Built

“Swimmer, a Cherokee shaman in western North Carolina, told me that formerly the Cherokees constructed mounds in the following manner: A fire was first kindled on the level surface. Around the fire was placed a circle of stones, outside of which were deposited the bodies of seven prominent men. A hollow cedar log to serve as a chimney or air hole was then fixed perpendicularly above the fire, and the earth was built up around this so as to form a mound. Upon this mound the town house was built, so that the mouth of the fire pit was in the middle of the town house floor. The fire was never allowed to go out, but was always smouldering at the bottom of the hole.

“Some time later, while talking with an intelligent woman in regard to local points of interest, she mentioned the large mound near Franklin, in Macon county, and remarked ‘There’s a fire at the bottom of that mound.’ Without giving her any idea what Swimmer had said, I inquired of her how the fire had got there, when she told substantially the same story. I found on investigation that the belief was general that the fires still existed. On mentioning this tradition to Cyrus Thomas, he stated that in many of the mounds — especially in some which he believed to be of Cherokee origin — there was found what seemed to be the remains of a perpendicular shaft or chimney, generally about a foot in diameter, coming up almost or quite to the top of the mound and running down into it to the original natural level of the ground, and sometimes a short distance below it. This shaft was always filled with ashes and charred remains of wood. No reasonable suggestion had hitherto been offered as to the purpose of these openings, but the Cherokee tradition- explained the whole thing. The roof of the Cherokee town house was covered with about a foot of earth; a new town house was usually built upon the site of the old, and as destruction by fire must have been a common accident, each successive burning causing a deposit of a layer of earth a foot or so in depth from the falling roof, it follows that this cause alone would result in time in raising the floor of the town house considerably above the surrounding surface, even if built originally upon the natural level.” — Mooney, Cherokee, 167, condensed.

Thomas calls into question the reliability of Cherokee tradition, in so far as it relates to mound building, and devotes twenty pages to a review of the evidence whiclt leads him to the conclusion that the Cherokees were the authors of the works in their territory.— Burial Mounds, 87-107.

THE MODERN INDIAN AS A BUILDER OF MOUNDS.

The subject of mound building by existing or known tribes will be next considered. No comment or explanation is necessary in connection with the quotations or statements, as their meaning and purpose are apparent.

Lucien Carr has made an exhaustive examination of early literature, proving conclusively that the Indian, as known to the whites, cultivated the ground extensively, was a sun worshipper, and constructed earthen mounds and enclosures, often of great size and area.

La Vega says: “The Indians try to place their villages on elevated sites; but inasmuch as in Florida there are not many sites of this kind where they can conveniently build, they erect elevations themselves in the following manner: They select the spot and carry there a quantity of earth which they form into a kind of platform two or three pikes in height, the summit of which is large enough to give room for twelve, fifteen or twenty houses, to lodge the cacique and his attendants. At the foot of this elevation [is] a square place around which the leading men have their houses. * * * To ascend the elevation they have a straight passage way from bottom to top, fifteen or twenty feet wide.” The village of Capaha “has about five hundred good houses, surrounded with a ditch ten or twelve cubits deep, and a width of fifty paces in most places, in others forty. The ditch is filled with water from a canal * * three leagues in length. * * The ditch * * surrounds the town except in one spot, which is enclosed by heavy beams planted in the earth.” — Essays, 73.

According to the Century Dictionary, “for some time later” than the fifteenth century, the pike was “from fifteen to twenty feet long. It continued in use, although reduced in length, throughout the seventeenth century.”

Biedma remarks: “The caciques of this region were accustomed to erect near the house where they lived very high mounds, and there were some who placed their houses on the top of these mounds.” — Essays, 74.

“The ‘Portugese Gentleman’ tells us that at the very spot where De Soto landed, generally supposed to be somewhere about Tampa Bay, at a town called Ucita, the house of the chief ‘stood near the shore upon a very high mound made by hand for strength.’ Such mounds are also spoken of by the Huguenot explorers. They served as the site of the chieftain’s house in the villages, and from them led a broad smooth road through the village to the water. These descriptions correspond closely to those of the remains which the botanists, John and William Bartram, discovered and reported about a century ago.”

“Within the present century the Seminoles of Florida are said to have retained the custom of collecting the slain after a battle and interring them in one large mound. The writer on whose authority I state this, adds that he ‘observed on the road from St. Augustine to Tomaka one mound which must have covered two acres of ground,’ but this must surely have been a communal burial mound.”

“M. Le Page du Pratz * * * observes that the one on which was the house of the Great Sun was ‘about eight feet high and twenty feet over on the surface.’ He adds that their temple * * * was on a mound about the same height.” — Essays, 75, 77, and 78.

“The Indians located along the Yazoo River ‘are dispersed over the country upon mounds of earth made with their own hands, from which it is inferred that these nations are very ancient and were formerly very numerous, although at the present time they hardly number two hundred and fifty persons.’ This language would seem to imply that at this time there were numerous mounds unoccupied.” — La Harpe (about A. D. 1700); in B. E. 12, 653.

“In one of their [the Natchez] villages Dumont notes that the •cabin of the chief was elevated on a mound. [See my blog on the Sacred Mound in Mississippi], Father Le Petit [says] the residence of the great chief or ‘Brother of the Sun,’ as he was called, was erected on a mound of earth carried for that purpose. When the chief died, the house was destroyed, and the same mound was not used as the site of the mansion of his successor, but was left vacant, and a new one was constructed. This interesting fact goes to explain the great number of mounds in some localities.” — Essays, 77.

La Vega in his history of Florida, page 231, speaking of a flood in the Mississippi, says that “During similar inundations, * * * the Indians contrive to live on any high or lofty ground or hills, or if there are none they build them with their own hands, principally for the dwelling of the caciques.” — B. E., 12, 626.

The name Florida was at that time applied to all the southern country east of the Mississippi.

The historians of De Soto make mention more than once of villages surrounded by walls, and ditches filled with water, the work of the Indians living in them.— B. E., 12, 669.

De Soto found that “on both sides of the [Mississippi] River, the natives lived in walled towns.” — Carr, Mounds, 526.

Lawson describes burial under mounds of earth and also of stone; but both seem to be very small.—Lawson, 42-3.

The celebrated shell mound at Old Enterprise, Florida, stands on a ridge partly on the original sea beach and partly on the swamp back of it. In this swamp live the mollusks whose shells have been so important in the construction of the mound. It is evident that the structure is formed of mud and marl brought to the spot from the swamp. After it had been carried to a sufficient height to maintain a dry surface, it was used as a dwelling site, and its elevation gradually increased by refuse from the houses and probably to some extent by additional material occasionally carried in from the swamp.— Dall.

A group of mounds located in the southern part of Union county, Mississippi, is supposed to mark the site of an Indian town near which De Soto encamped one winter. In one of the mounds, which was at least ten feet high before its reduction by cultivation, three feet above the original surface was a saucer-shaped bed of fine ashes six feet in diameter, six inches thick at the center, and running out to an edge on every side. There was no evidence of fire on the earth above or below, and there were many thin layers as though the ashes had been carried in small quantities and carefully spread out. Within an inch of the bottom of the ashes was a small fragment of glass, apparently broken from a thick bottle. Resting upon the ashes, though not extending to the edge at any part, was a confused mass twelve inches thick of charcoal, soil, ashes, and broken pottery, in which lay an iron knife and a thin silver plate stamped with the arms of Castile and Leon. This seemed an intrusive deposit as there was an unconformity between it and the surrounding earth; but if the mound had ever been opened since its construction, such excavation antedated the settlement of the country by the whites, for the first man who settled in the region was at that time still living only a few rods from the mound and was positive in his statement that it had never been disturbed. At any rate, it would have been impossible to restore the ash-bed to its former condition had it ever been broken; and that it was coeval with the body of the structure is proven by the fact that it reached into undisturbed earth on every side. Moreover, there were found just above the ashes several pieces of glass similar to that which lay five inches beneath their surface, two or three of them being chipped into the form of gunflints, possibly for scrapers. The knife-blade was almost destroyed by rust; the silver plate was not at all corroded, though a hole had been made in one end apparently to suspend it by. There was no trace of bone or other evidence of burial anywhere in the mound; but as the entire mass of clay of which it was composed was very wet and sticky, a skeleton would have disappeared within a comparatively short time. It is quite probable that this mound was opened by the Indians themselves very soon after it was made, and the loose earth, with the relics mentioned placed or thrown in. As the whole group was of one character and apparently of one period, we are justified in placing the date of their construction at about the middle of the sixteenth century — some of them earlier, perhaps, some of them later. Of the eleven mounds opened only this one contained anything of European origin.

The supposed winter camp of De Soto, on the Tallahatchie river, is seven miles from this place.

Jefferson, in his “Notes on Virginia,” describes a mound opened by him near Charlottesville; it was plainly an ossuary containing the bones of those who had died at different times or places and were brought hither for interment. He estimates their number at not less than one thousand. He further relates that about the middle of the last century a party of Indians traveling through this section had, without inquiry or instruction, diverged several miles from their road and taken a straight course through the woods to this sepulcher, where they remained several hours seemingly mourning over the dead. Unfortunately, it is not told to what tribe they belonged; had he recorded this, it might have dispelled our ignorance concerning the authors of the mounds in eastern Virginia.

Glass beads and iron bracelets were found with skeletons at the bottom of a mound at Lenoir’s, Tennessee. — B. E. 12, 398.

“The Cherokees were in the habit of using just such ornaments as are found in these mounds [in Cherokee territory].” Articles of various sorts found in the mounds of Eastern Tennessee are “precisely similar” to others found about Indian village sites in connection with objects of European make, and answer the description given by early writers of ornaments and utensils made and used by Indians in this locality as well as in Virginia.— Burial Mounds, 94.

“If we can point out a well known race of Indians who. at the time of the discovery, raised mounds and other earthworks, not wholly dissimilar in character and not much inferior in size to those in the Ohio Valley, and who resided not very far away from that region and directly in the line which the Mound Builders are believed by all to have followed in their emigration, then this rule [that the simplest explanation of a given fact or series of facts should always be accepted] constrains us to accept for the present this race as the most probable descendants of the Mound Builders, and seek no further for Toltecs, Asiatics or Brazilians. All these conditions are filled by the Chahta tribes.”

“I believe that the evidence is sufficient to justify us in accepting this race [the Chahta-Muskokees] as the constructors of all those extensive mounds, platforms, artificial lakes and circumvallations which are scattered over the Gulf States, Georgia and Florida. The earliest explorers distinctly state that such were used and constructed by these nations in the sixteenth century, and probably had been for many generations.” — Essays, 79 and 80.

“Major Sibley * * stated that an ancient chief of the Osage Indians informed him while he was a resident among them, that a large conical mound, which he. Major Sibley was in the habit of seeing every day whilst he resided amongst them, was constructed when he was a boy. That a chief of his nation * * had unexpectedly died whilst all the men of his tribe were hunting in a distant country. His friends buried him in the usual manner, with his weapons, his earthen pot, and the usual accompaniments, and raised a small mound over his remains. When the nation returned from the hunt, this mound was enlarged at intervals, every man assisting to carry materials, and thus the accumulation of earth went on for a long period until it reached its present height, when they dressed it off at the top to a conical form. The old chief farther said that he had been informed and believed, that all the mounds had a similar origin.” — Featherstonehaugh, 70.

According to later authors, the “old chief” was not above playing tricks upon travelers.

“Mr. Collet, of St. Louis, says he made a search for this mound, but was unable to find it.” — B. E. 12, 658.

Snyder goes still farther, and denies there are any artificial mounds whatever in that part of Missouri, and asserts that all such features are produced “by aqueous or glacial action.” although Indian burials may have been made upon some of the latter. “I traversed the entire valley of the Osage River. * * * I saw no artificial earthen mounds there of any -description.” — Snyder, Osages.

At Bellaire, Michigan, north-east from Traverse City, in a mound four feet high and twenty feet in diameter, with a slight depression around the base, was a skeleton, sitting, with feet extended. By it was the outer whorl of a Busycon shell, the outer surface of which was covered with incised lines crossing each other practically at right angles. The skull was very thin, compact as ivory almost, and unusually symmetrical. The crown and forehead were very full and prominent, indicating a high intellectual development. There was nothing Indian in its appearance, and its presence under such conditions is puzzling. Possibly one of the early Jesuits was interred here by his proselytes.

On Rapid river near Traverse City, Michigan, are two mounds, each about six feet high and twenty feet across. An old Chippewa told me that one was erected over Sioux, the other over Chippewas, slain in a battle here in the latter part of the eighteenth century. Several small mounds in upper Michigan cover Sioux, Iroquois and Chippewas; the Indians about there preserve traditions of the fights in which these were slain and in some cases know the name or family of one who is buried in a given tumulus. A few years ago one of these mounds was opened by some wood-cutters and the bones scattered around. The Indians were furious when they knew of it, and endeavored to find the perpetrators, swearing to slay them if they could be identified.

“A small burial mound on the west shore of Ottawa Point” was opened. “The utensils, trinkets, &c, were all of a period subsequent to the advent of the white man.” Consequently, Mr. Gillman decides that this mound was not built by a Mound Builder. He says “such mounds are frequent all along the lake shore, and seems to be invariably of more recent origin than the first-described works. They are generally quite small.” — Gillman, M. B., 379.

There is a considerable number of other mounds in the region within a hundred miles around Mackinac Island, which are known to be the work of Sioux, Chippewas and Iroquois. There are traditions, also, among the two first named, of a race in Wisconsin and Minnesota, known as the “Ground House Indians” from their .custom of banking and covering their houses with earth; they buried their dead in mounds near the dwellings. These were exterminated in the first half of the seventeenth century.—O. A. H., Dec, 1888.

“I must remark that whatever be the legitimate inference drawn from similar works and remains in other places, concerning the state of civilization attained by the Mound Builders, the evidence here [he had been exploring in the vicinity of Racine] goes to prove that they were an extremely barbarous people, in no respect superior to most of the savage tribes of modern Indians.” — Dr. P. R. Hoy: quoted by Lapham, 10.

At the Pipe-Stone quarries “is a mound of a conical form, of ten feet height, which was erected over the body of a distinguished young man, son of a Sioux chief.” who was killed there about 183-5.— Catlin, Indians. II, 170, note.

Major Powell “has himself seen two burial mounds in process of construction — one in Utah, * * * the other * * * in the valley of the Pitt river.” “The evidence in favor of the Indian origin of the western structures has been so great and the facts have been so well known that writers have rarely attributed them to prehistoric peoples.” — Introduction. B. E. 12, xlvii.