I have compiled some fantastic information about the mummies we have all heard about in the life of Joseph Smith and the Church, as well as other mummies found in North America.

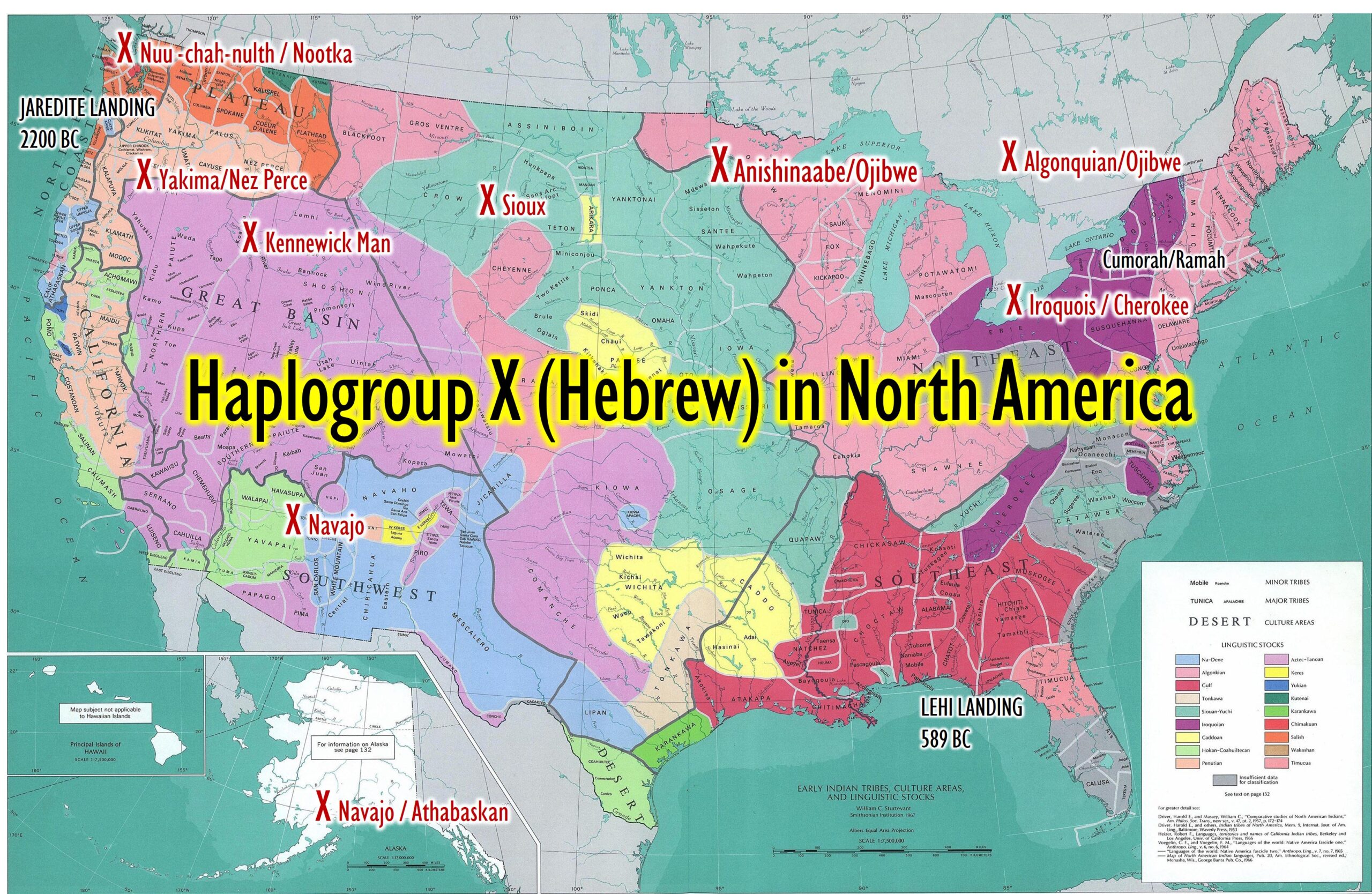

As you probably know, an anachronism is, an error in respect to dates; any error which implies the misplacing of persons or events in time; hence, anything foreign to or out of keeping with a specified time. Finding mummies in North America is one of those anachronisms that we will discuss. Ther are many other anachronisms found in the Book of Mormon text. (i.e. Horses, elephants, barley, steel swords, etc)

The connection of the Old World of Egypt, Israel and the Middle East have so many amazing connections with the Land of Joseph here in North America. I find no such similarities in Mesoamerica or South America. This blog may be long for some, but once again I have added much information so you can read some today and maybe in a day or two, but you will always have this information to go back and study about Joseph Smith and the Mummies.

First I briefly touch on an article found in the Times and Seasons called “A Catacomb of Mummies Found in Kentucky.”

“Lexington, in Kentucky, stands nearly on the site of an ancient town, which was of great extent and magnificence, as is amply evinced by the wide range of its circumvalliatory works, and the quantity of ground it once occupied. There was connected with the antiquities of this place, a catacomb, formed in the bowels of the limestone rock, about fifteen feet below the surface of the earth, adjacent to the town of Lexington.

This grand object, so novel and extraordinary in this country, was discovered in 1775, by some of the first settlers, whose curiosity was excited by something remarkable in the character of the stones which covered the entrance to the cavern within. They removed these stones, and came to others of singular appearance for stones in a natural state; the removal of which laid open the mouth of a cave, deep, gloomy, and terrific, as they supposed. With augmented numbers, and provided with light, they descended and entered, without obstruction, a spacious apartment; the sides and extreme ends were formed into niches and compartments, and occupied by figures representing men. When alarm subsided, and the sentiment of dismay and surprise permitted further research and inquiry, the figures were found to be mummies, preserved by the art of embalming, to as great a state of perfection as was known among the ancient Egyptians, eighteen hundred years before the Christian era; which was about the time that the Israelites were in bondage in Egypt, when this art was in its perfection. * * * * *

On this subject Mr. Ash has the following reflections: “How these bodies were embalmed, how long preserved, by what nations, and from what people descended, no opinion can be formed, nor any calculation made, but what must result from speculative fancy and wild conjecture. For my part, I am lost in the deepest ignorance. My reading affords me no knowledge, my travels no light. I have neither read nor known of any of the North American Indians who formed catacombs for their dead, or who were acquainted with the art of preservation by embalming. Had Mr. Ash in his researches consulted the Book of Mormon his problem would have been solved, and he would have found no difficulty in accounting for the mummies being found in the above mentioned case. The Book of Mormon gives an account of a number of the descendants of Israel coming to this continent; and it is well known that the art of embalming was known among the Hebrews, as well as among the Egyptians, although perhaps not so generally among the former, as among the latter people; and their method of embalming also might be different from that of the Egyptians. [781]

Jacob and Joseph were no doubt, embalmed in the manner of the Egyptians, as they died in that country, Gen. 1, 2, 3, 26. When our Saviour was crucified his hasty burial obliged them only to wrap his body in linnen with a hundred pounds of myrrh, aloes, ahd similar spices, (part of the ingredients of embalming.) given by Nicodemus for that purpose: but Mary and other holy women had prepared ointment and spices for embalming it, Matt. xxviii. 59: Luke xxiii. 56: John xxx. 39, 40. This art was no doubt transmitted from Jerusalem to this continent, by the before mentioned emigrants, which accounts for the finding of the mummies, and at the same time is another strong evidence of the authenticity of the Book of Mormon.” Times and Seasons (Nauvoo, Illinois) 3, no. 13 (2 May 1842): 781–82. A CATACOMB OF MUMMIES FOUND IN KENTUCKY

Part 1: Mummies of Joseph Smith

“During the summer of 1835, while the apostles left on missions to the eastern states and Canada, the Saints worked together to finish the temple and prepare for the endowment of power. Spared the violence and loss the Saints in Missouri had suffered, Kirtland grew and prospered spiritually as converts gathered to the town and lent their hands to the Lord’s work.1

“During the summer of 1835, while the apostles left on missions to the eastern states and Canada, the Saints worked together to finish the temple and prepare for the endowment of power. Spared the violence and loss the Saints in Missouri had suffered, Kirtland grew and prospered spiritually as converts gathered to the town and lent their hands to the Lord’s work.1

In July, a poster advertising “Egyptian Antiquities” appeared in town. It told of the discovery of hundreds of mummies in an Egyptian tomb. Some of the mummies, as well as several ancient papyrus scrolls, had been exhibited throughout the United States, attracting large crowds of spectators.2

Michael Chandler, the man showcasing the artifacts, had heard of Joseph and come to Kirtland to see if he wanted to purchase them.3 Joseph examined the mummies, but he was more interested in the scrolls. They were covered with strange writing and curious images of people, boats, birds, and snakes.4 Chandler permitted the prophet to take the scrolls home and study them overnight. Joseph knew Egypt played an important role in the lives of several prophets in the Bible. He also knew Nephi, Mormon, and other writers of the Book of Mormon had recorded their words in what Moroni called “reformed Egyptian.”5 As he examined the writings on the scrolls, he discerned that they contained vital teachings from the Old Testament patriarch Abraham. Meeting with Chandler the next day, Joseph asked how much he wanted for the scrolls.6 Chandler said he would only sell the scrolls and mummies together, for $2,400.7

The price was far more than Joseph could afford. The Saints were still struggling to finish the temple with limited funds, and few people in Kirtland had money to loan him. Yet Joseph believed the scrolls were worth the price, and he and others quickly raised enough money to buy the artifacts.8

Excitement rippled through the church as Joseph and his scribes began trying to make sense of the ancient symbols, confident the Lord would soon reveal more of their message to the Saints.9

When Joseph was not poring over the scrolls, he put them and the mummies on display for visitors. Emma took a keen interest in the artifacts and listened carefully as Joseph explained his understanding of the writings of Abraham. When curious people asked to see the mummies, she often exhibited them herself, sharing what Joseph had taught her.10 Source: Saints Chapter 20 Do Not Cast Me Off

NOTES Chapter 20: Do Not Cast Me Off

- William W. Phelps to Sally Waterman Phelps, June 2, 1835, in JSP, D4:335–36; William W. Phelps to Sally Waterman Phelps, in Historian’s Office, Journal History of the Church, July 20, 1835; this entry was copied from the original letter in possession of a grandson of William W. Phelps. Topic: Kirtland, Ohio219

- Historical Introduction to Book of Abraham Manuscript, circa Early July–circa Nov.1835–A Abraham 1:4–2:6], in JSP, D5:71–77; “Egyptian Antiquities,” Times and Seasons, May 2, 1842, 3:774.

- Joseph Smith History, 1838–56, volume B-1, 595–96; “Egyptian Antiquities,” Times and Seasons, May 2, 1842, 3:774; Oliver Cowdery to William Frye, Dec. 22, 1835, in Oliver Cowdery, Letterbook, 68–74; “Egyptian Mummies,” LDS Messenger and Advocate, Dec. 1835, 2:234–35; Certificate from Michael Chandler, July 6, 1835, in JSP, D4:361–65.220

- “Egyptian Mummies,” LDS Messenger and Advocate, Dec. 1835, 2:234–35; see also “Egyptian Papyri,” at josephsmithpapers.org.220

- Historical Introduction to Certificate from Michael Chandler, July 6, 1835, in JSP, D4:362; Tullidge, “History of Provo City,” 283; William W. Phelps to Sally Waterman Phelps, in Historian’s Office, Journal History of the Church, July 20, 1835; Mormon 9:32.220

- Joseph Smith History, 1838–56, volume B-1, 596; Oliver Cowdery to William Frye, Dec. 22, 1835, in Oliver Cowdery, Letterbook, 68–74; Historical Introduction to Certificate from Michael Chandler, July 6, 1835, in JSP, D4:362; Tullidge, “History of Provo City,” 283.220

- JSP, D4:363, note 9; Joseph Coe to Joseph Smith, Jan. 1, 1844, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library; Orson Pratt, in Journal of Discourses, Aug. 25, 1878, 20:65.220

- Joseph Coe to Joseph Smith, Jan. 1, 1844, Joseph Smith Collection, Church History Library; Peterson, Story of the Book of Abraham, 6–8.220

- William W. Phelps to Sally Waterman Phelps, in Historian’s Office, Journal History of the Church, July 20, 1835. Topic: Book of Abraham Translation22

- Lyman and others, No Place to Call Home, 44.

The Joseph Smith Foundation- Bruce H. Porter

Eleven mummies, found by Lebolo were eventually sent to the United States, four of which were purchased by the church in Kirtland in 1835. The history of the mummies was published in a church publication in December of 1835. It reads:

“The public mind has been excited of late, by reports which have been circulated concerning certain Egyptian mummies and ancient records which were purchased by certain gentlemen of Kirtland, last July… The records were obtained from one of the catacombs in Egypt, near the place where one stood the renowned city of Thebes, by the celebrated French Traveler, Antonio Lebolo in the year 1831. He procured license from Mehemet Ali, then Viceroy of Egypt, under the protection of Chevalier Drovetti, the French Consul, in the year 1828; employed 433 men four months and two days (if I understood correctly, Egyptian or Turkish soldiers), at from four to six cents per diem, each man entered the catacomb June 7, 1831, and obtained eleven mummies in the same catacomb: about one hundred embalmed after the first order, and deposited and placed in niches, and two or three hundred after the second and third order, and laid upon the floor or bottom of the grand cavity, the two last orders of embalmed were so decayed that they could not be removed, and only eleven of the first, found in the niches. On the way from Alexandria to Paris, he put in at Trieste, and after ten days illness, expired. This was in the year 1832. Previous to his decease, he made a will of the whole to Mr. Michael H. Chandler, then in Philadelphia, Pa. his nephew whom he supposed to have been in Ireland. Accordingly the whole were sent to Dublin, addressed according, and Mr. Chandler’s friends ordered them sent to New York, where they were received at the custom house, in the winter or spring of 1833. In April of the same year, Mr. Chandler paid the duties upon his Mummies, and took possession of the same. Up to this time they had not been taken out of the coffins nor the coffins opened. On opening the coffins he discovered that in connection with two of the bodies, were something rolled up with the same kind of linen, saturated with the same bitumen, which, when examined, proved to be two rolls of papyrus, previously mentioned. I may add that two or three other small pieces of papyrus, with astronomical calculations, epitaphs, etc. were found with others of the Mummies.1″

Concerning the discovery, we must rely on sources that are not even second hand. According to the Chandler/Cowdery account, it states that the records and mummies came from the area of Thebes and were discovered by Antonio Lebolo. There is no question that this is possible, since Lebolo worked almost exclusively in the vicinity of Thebes. He also carried out excavations on his own as is seen with the Soter find and probable others.2 As to the date, there is a problem. I am unaware of any record of Lebolo being in Egypt after December of 1821. Balboni, Gl’Italiani nella Civilta Egiziana, 307, 308. Balboni, in his book has a copy of a letter written by Lebolo to Segate, dated November 25, 1821, Lebolo being in Egypt at that time. Lebolo’s marriage record is dated June 12, 1824 at Venice. The record states, “…born in Castellamonte…presently domiciled in Alexandria Egypt” (H. Donl Peterson, “Mummies and Manuscripts,” 1980). This does not mean in any way that he could not have been or would not have been in Egypt any number of times after 1821. Dawson, in his Who Was Who, states that Lebolo died in Trieste in 1823. The second edition leaves the death date open in light of Cowdery’s account above.”‘3 However, this is not possible since the church register in Castellamonte records Lebolo’s death there on February 19, 1830.’4 Was Chandler mistaken on the death date? Was he misinformed? Was it Lebolo at all that discovered the tomb? The date for the discovery by Lebolo himself is wrong; of this, there is no doubt. Even if the discovery took place on “June 7, 1831” as stated by Chandler/Cowdery, the time allowed to accomplish all that the report indicated would be questionable.5 Although we can only make assumptions about the difference in dating, other details that Chandler gave about the mummies incline us to question his veracity. “He procured license from Hememet Ali.” This would have had to have been done in order to “personally” excavate in Egypt at that time. If Lebolo was acting as an independent, he would need a license from Ali. However, if he were operating as an agent of Drovetti, “with permission to ascertain a personal collection,”7 The license was procured by Lebolo, according to Chandler/Cowdery, in 1828. This very well could have been if Lebolo had returned to do excavations on his own. The report then speaks of Lebolo employing 433 men, four months and two days (such exact numbers!). This is not hard to believe in light of Vidua’s comment that Lebolo would sometimes have up to “three hundred men at his command.”8 According to this account, after entering the tomb, they obtained eleven mummies; probably those had coffins and could be removed intact. It would be surprising if there were not more than eleven coffins in the tomb, and as habit dictated in the past, the better ones were opening looking for valuable artifacts.”‘9 “One hundred mummies after the first order, and ‘one to two hundred after the second and third order’ were contained in the tomb.” Of the two to three hundred mummies in the tomb, most were in such a state of decay that only eleven could be removed. As Henniker stated, there were more than fourteen mummies in the Soter tomb and all but those fourteen were too decayed to be removed.”10 Belzoni speaks of such a tomb as described by Chandler/Cowdery:

Concerning the discovery, we must rely on sources that are not even second hand. According to the Chandler/Cowdery account, it states that the records and mummies came from the area of Thebes and were discovered by Antonio Lebolo. There is no question that this is possible, since Lebolo worked almost exclusively in the vicinity of Thebes. He also carried out excavations on his own as is seen with the Soter find and probable others.2 As to the date, there is a problem. I am unaware of any record of Lebolo being in Egypt after December of 1821. Balboni, Gl’Italiani nella Civilta Egiziana, 307, 308. Balboni, in his book has a copy of a letter written by Lebolo to Segate, dated November 25, 1821, Lebolo being in Egypt at that time. Lebolo’s marriage record is dated June 12, 1824 at Venice. The record states, “…born in Castellamonte…presently domiciled in Alexandria Egypt” (H. Donl Peterson, “Mummies and Manuscripts,” 1980). This does not mean in any way that he could not have been or would not have been in Egypt any number of times after 1821. Dawson, in his Who Was Who, states that Lebolo died in Trieste in 1823. The second edition leaves the death date open in light of Cowdery’s account above.”‘3 However, this is not possible since the church register in Castellamonte records Lebolo’s death there on February 19, 1830.’4 Was Chandler mistaken on the death date? Was he misinformed? Was it Lebolo at all that discovered the tomb? The date for the discovery by Lebolo himself is wrong; of this, there is no doubt. Even if the discovery took place on “June 7, 1831” as stated by Chandler/Cowdery, the time allowed to accomplish all that the report indicated would be questionable.5 Although we can only make assumptions about the difference in dating, other details that Chandler gave about the mummies incline us to question his veracity. “He procured license from Hememet Ali.” This would have had to have been done in order to “personally” excavate in Egypt at that time. If Lebolo was acting as an independent, he would need a license from Ali. However, if he were operating as an agent of Drovetti, “with permission to ascertain a personal collection,”7 The license was procured by Lebolo, according to Chandler/Cowdery, in 1828. This very well could have been if Lebolo had returned to do excavations on his own. The report then speaks of Lebolo employing 433 men, four months and two days (such exact numbers!). This is not hard to believe in light of Vidua’s comment that Lebolo would sometimes have up to “three hundred men at his command.”8 According to this account, after entering the tomb, they obtained eleven mummies; probably those had coffins and could be removed intact. It would be surprising if there were not more than eleven coffins in the tomb, and as habit dictated in the past, the better ones were opening looking for valuable artifacts.”‘9 “One hundred mummies after the first order, and ‘one to two hundred after the second and third order’ were contained in the tomb.” Of the two to three hundred mummies in the tomb, most were in such a state of decay that only eleven could be removed. As Henniker stated, there were more than fourteen mummies in the Soter tomb and all but those fourteen were too decayed to be removed.”10 Belzoni speaks of such a tomb as described by Chandler/Cowdery:

“After the exertion of entering into such a place, through a passage of fifty, a hundred, three hundred, or perhaps six hundred yards, nearly overcome, I sought a resting-place, found one, and contrived to sit; but when my weight bore on the body of an Egyptian, it crushed like a bandbox. I naturally had recourse to my hands to sustain my weight, but they found no better support; so that I sank altogether among the broken mummies, with a crash of bones, rags, and wooden cases, which raised such a dust as kept me motionless for a quarter of an hour, waiting till it subsided again. I could not remove from the place, however, without increasing it, and every step I took I crushed a mummy in some part or another. Once I was conducted from such a place to another resembling it through a passage of about twenty feet in length, no wider than body could be forced through. It was choked with mummies, and I could not pass without putting my fact in contact with that of some decayed Egyptian; but as the passage inclined downwards, my own weight helped me on; however, I could not avoid being covered with bones, legs, arms, and heads rolling from above. Thus, I proceeded from one cave to another all full of mummies piled up in various ways some standing, some lying, and some on their heads. The purpose of my researches was to rob the Egyptians of their papyri; of which I found a few hidden in their breasts, under their arms, in the space above the knees, on the leg, and covered by numerous folds of cloth that envelop the mummy.11″

It is possible that this large number of mummies could have been in the tomb with the eleven that Chandler received. However, there is one problem. There are not that many known tombs in Qurna that could accommodate two or three hundred living, much less mummified, people. Could the eleven mummies that Chandler received have come from more than one tomb? Could they derive from Lebolo’s last collection, sold after his death? Lebolo did not make a will leaving the eleven mummies to Michael H. Chandler. The will of Antonio Lebolo was found in the fall of 1984 and contained no mention of a Michael H. Chandler, or the eleven mummies. The will itself was over two hundred pages, most of which listed Lebolo’s belongings. From his will, Lebolo obviously passed away a wealthy and influential man in his community.12 Where then did the eleven mummies that Michael Chandler acquired from? At the time the will was found, and in the same archives, the heirs of Antonio Lebolo were filing suit against one Alban Oblasser, dated July 30, 1831. This suit charged Oblasser, who then resided in Trieste, of the sale of “eleven mummies” that he had been given by Lebolo to sell on consignment. The sale of these mummies by Oblasser left monies owing the estate of the Lebolo heirs.”13 Could these “eleven mummies” be the same “eleven mummies” that Chandler received? Another account of Chandler receiving the mummies is giving in 1842 by P. P. Pratt.

It is possible that this large number of mummies could have been in the tomb with the eleven that Chandler received. However, there is one problem. There are not that many known tombs in Qurna that could accommodate two or three hundred living, much less mummified, people. Could the eleven mummies that Chandler received have come from more than one tomb? Could they derive from Lebolo’s last collection, sold after his death? Lebolo did not make a will leaving the eleven mummies to Michael H. Chandler. The will of Antonio Lebolo was found in the fall of 1984 and contained no mention of a Michael H. Chandler, or the eleven mummies. The will itself was over two hundred pages, most of which listed Lebolo’s belongings. From his will, Lebolo obviously passed away a wealthy and influential man in his community.12 Where then did the eleven mummies that Michael Chandler acquired from? At the time the will was found, and in the same archives, the heirs of Antonio Lebolo were filing suit against one Alban Oblasser, dated July 30, 1831. This suit charged Oblasser, who then resided in Trieste, of the sale of “eleven mummies” that he had been given by Lebolo to sell on consignment. The sale of these mummies by Oblasser left monies owing the estate of the Lebolo heirs.”13 Could these “eleven mummies” be the same “eleven mummies” that Chandler received? Another account of Chandler receiving the mummies is giving in 1842 by P. P. Pratt.

“A gentleman, travelling in Egypt, made a selection of several mummies, of the best kind of embalming, and of course, in the best state of preservation; on his way to England he died, bequeathing them to a gentleman of the name of Chandler. They arrived in the Thames, but it was found the gentleman was in America, they were then forwarded to New York and advertised, when Mr. Chandler came forward and claimed them. One of the mummies, on being unrolled, had underneath the cloths in which it was wrapped, lying upon the breast, a roll of papyrus, in an excellent state of preservation, written in Egyptian character, and illustrated in the manner of our ingraving, which is a copy from a portion of it. The mummies, together with the record, have been exhibited, generally, throughout the States, previous to their falling into our hands.14″

In light of the “Oblasser suit,” this account seems even more plausible than the Chandler/Cowdery “will” story. However Chandler came by the mummies, in “April of 1833” he paid the duty and took possession of them. From New York “he took his collection to Philadelphia, where he exhibited them for a compensation.” Cowdery continues, “from Philadelphia he visited Harrisburgh, and other places east of the mountains.” Newspaper accounts and advertisements verify that Chandler did exhibit his collection. A Philadelphia newspaper contained the following:

EGYPTIAN MUMMIES

The largest collection of EGYPTIAN MUMMIES ever exhibited in this city, is now to be seen at the Masonic Hall, in Chestnut Street above Seventh. They were found in the vicinity of Thebes, by the celebrated traveler Antonio Lebolo and Chevalier Drovetti, General Consul of France in Egypt. Some writings on Papirus [sic] found with the mummies, can also be seen, and will afford, no doubt, much satisfaction to Amateurs of Antiquites. Admittance 25 cents, children half price. Open from 9 A.M. till 2 P.M., and from 3 P.M. to 6. Ap 3 – d3W This article began on April 3rd and ran for three weeks.15 The Hartford Republican ran this note while the mummies were on exhibition in Philadelphia: “Nine mummies, recently found in the vicinity of Thebes, are now exhibiting at the Masonic Hall, Philadelphia.”16 By this time two mummies were already missing from the collection of eleven. In Pratt’s account above, Chandler opened one coffin and unrolled one mummy at the customs house. Cowdery, in speaking of this incident, says: “When Dr. Chandler discovered that there was something with the Mummies, he supposed, or hoped it might be some diamonds or other valuable metal, and was no little chagrined when he saw his disappointment.””17 As noted above, one mummy may have been destroyed at the customs house while Chandler searched it for the gold of the Pharaohs. Two mummies appear to have been bought by Samuel George Morton in Philadelphia. He lists in his Catalogue of Skulls under item numbers 48, 60, “48. Embalmed head of an Egyptian girl, eight years of age, from the Theban catacombs. Egyptithan form, with a single lock of long fine hair.18 Dissected by me before the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, December 10, 1833.” There is little question that this mummy came from the Chandler mummies. Entry number 60 leaves no doubt: “Embalmed head of an Egyptian lady about 16 years of age, brought from the catacombs of Al Gourna, near Thebes, by the late Antonio Lebolo, of whose heirs I purchased it, together with the entire body; the latter dissected before the Academy of Natural Sciences, on the 10th and 17th of December, 1833, in the presence of eight members and others. Egyptian form, with long fine hair.” By the time Chandler reached Baltimore, the number of mummies had dwindled to six. We read: “P.S. The citizens are respectfully informed that the Manager has received from the vicinity of Thebes that celebrated city of Ancient Egypt, Six strangers illustrious from their antiquity, count probably an existence at least 1,000 years anterior to the advent of our blessed Savior…”19

The largest collection of EGYPTIAN MUMMIES ever exhibited in this city, is now to be seen at the Masonic Hall, in Chestnut Street above Seventh. They were found in the vicinity of Thebes, by the celebrated traveler Antonio Lebolo and Chevalier Drovetti, General Consul of France in Egypt. Some writings on Papirus [sic] found with the mummies, can also be seen, and will afford, no doubt, much satisfaction to Amateurs of Antiquites. Admittance 25 cents, children half price. Open from 9 A.M. till 2 P.M., and from 3 P.M. to 6. Ap 3 – d3W This article began on April 3rd and ran for three weeks.15 The Hartford Republican ran this note while the mummies were on exhibition in Philadelphia: “Nine mummies, recently found in the vicinity of Thebes, are now exhibiting at the Masonic Hall, Philadelphia.”16 By this time two mummies were already missing from the collection of eleven. In Pratt’s account above, Chandler opened one coffin and unrolled one mummy at the customs house. Cowdery, in speaking of this incident, says: “When Dr. Chandler discovered that there was something with the Mummies, he supposed, or hoped it might be some diamonds or other valuable metal, and was no little chagrined when he saw his disappointment.””17 As noted above, one mummy may have been destroyed at the customs house while Chandler searched it for the gold of the Pharaohs. Two mummies appear to have been bought by Samuel George Morton in Philadelphia. He lists in his Catalogue of Skulls under item numbers 48, 60, “48. Embalmed head of an Egyptian girl, eight years of age, from the Theban catacombs. Egyptithan form, with a single lock of long fine hair.18 Dissected by me before the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, December 10, 1833.” There is little question that this mummy came from the Chandler mummies. Entry number 60 leaves no doubt: “Embalmed head of an Egyptian lady about 16 years of age, brought from the catacombs of Al Gourna, near Thebes, by the late Antonio Lebolo, of whose heirs I purchased it, together with the entire body; the latter dissected before the Academy of Natural Sciences, on the 10th and 17th of December, 1833, in the presence of eight members and others. Egyptian form, with long fine hair.” By the time Chandler reached Baltimore, the number of mummies had dwindled to six. We read: “P.S. The citizens are respectfully informed that the Manager has received from the vicinity of Thebes that celebrated city of Ancient Egypt, Six strangers illustrious from their antiquity, count probably an existence at least 1,000 years anterior to the advent of our blessed Savior…”19

On September 9, 1833, we see in the Harrisburg Chronicle: “SIX EGYPTIAN MUMMIES now exhibiting in the Masonic Hall, Harrisburg.” By the time Chandler reached Cleveland in 1835, he was tired of “life on the road.” Following the typical advertisement of the mummies we read: “The collection is offered for sale by the Proprietor.”20 About three months later, they were bought by the church in Kirtland, Ohio. In the journal of Joseph Smith, it reads for the date of July 3, 1835: “On the 3rd of July, Michael H. Chandler came to Kirtland to exhibit some Egyptian mummies. There were four human figures, together with some two or more rolls of papyrus covered with hieroglyphic figures and devices.”21 On the 6th of July “some of the Saints at Kirtland purchased the mummies and papyrus.”22 Joseph Smith then kept the mummies and papyrus in his possession until his death in 1844. They then passed to his mother who kept them until her death in 1855. Eventually it appears that they were acquired by the Woods Museum in Chicago. After the great Chicago fire of 1871, it was believed that the mummies and papyrus had been destroyed. In 1966, some fragments of the Joseph Smith Papyri were found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, hinting that perhaps at least some of this Lebolo collection may still be found. The church obtained ownership of the eleven fragments of papyri in November of 1967. They are now housed in the Church Archives in Salt Lake City, Utah.

- Messenger and Advocate, 2:3 (December, 1835); 232-33. This was recorded by Oliver Cowdery, who interviewed Michael H. Chandler within six months of the purchase.

- It would be naive to assume that Lebolo did no digging on his own, or did no more than the Soter excavation, when considering Lebolo sold his own collections to the Vatican and to Burghart for the Imperial Museum of Vienna.

- Dawson and Uphill, Who Was Who, 166. Speaking of the mummies Uphill states that “Further ones appear to have been received in America…which if correct shows that Lebolo cannot have died in 1823 as previously thought.”

- A copy of Lebolo’s death entry is in the position of H. Donl Peterson. It reads: “1830 Lebolo Antonio the wife of whom is Anna Dufour, African woman, son of Pietro and Marianna Meuta, aged of fifty years, provided with sacraments, died on the nineteenth day of February and the next day buried.

- If the discovery took place in June of 1831, the mummies would then have to be removed and transported from Qurna to Cairo, and from there to Alexandra. Once there, they would have to be packed and crated for the voyage to Trieste where they would need to be unloaded and moved to where Lebolo was to die. Once the will was probated (and the freight paid), the mummies were then to proceed to Ireland. After the search for Michael CHandler failed, his “friends” sent them to New York. From the date of entering the tomb to the time Chandler recieved the mumies was about twenty-two months. It is possible, but not probable.

- “Marro Papers.” Marro’s summary of Lebolo. See note 8 above. he would need no license, but would then be “under the protection of” Drovetti.°6 Vidua, in letter No. 34, writes that even the “Turkish commander respects him (Lebolo) for fear of Mr. Drovetti.”

- Ibid.

- Henniker, Notes, 137. See notes 30 and 31 above.

- Ibid.

- Mayes, The Great Belzoni, 160.

- The will is housed in the state archives in Torino. Mr. Comollo, H. Donl Peterson and myself were in Torino for the purpose of locating the will when it was found. Copies of the will are in the possession of Professor Peterson and myself.

- A copy of this suit is in the possession of H. Donl Peterson as well as myself.

- The Latter-Day Millennial Star, 3:3 (July, 1842), 46.

- U. S. Gazette, published by Joseph R. Chandler, Philadelphia, Wednesday, April 3, 1833, p. 3.

- The Hartford Republican, Belle Air, Hartford County, Maryland, 3:41 (Thursday, May 23, 1833):1.

- Messenger and Advocate, p. 234.

- Samuel George Morton, Catalogue of Skulls, (Philadelphia: Merrihew and Thompson, 1849), 38, 39. Both of these mummies were from Thebes and were dissected the same day by Morton.

- American and Commercial Daily Advertiser, Baltimore, July 22, 1833. This article was under the section for the Baltimore Museum and ran through August 9, 1833.

- Cleveland Advertiser, Cleveland, Ohio, Thursday, March 26, 1835.

- Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret, 1973), 2:235.

- Ibid., p. 236.

Source: The Joseph Smith Foundation- Bruce H. Porter

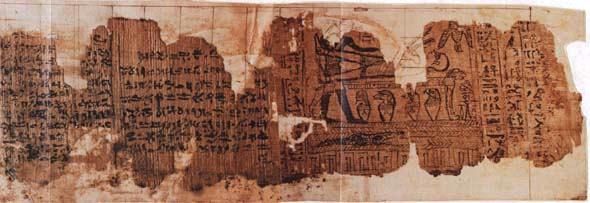

Introduction to Egyptian Material

Napoleon Bonaparte’s late eighteenth-century adventures, depredations, and exploits unintentionally inaugurated an age of exploration and inquiry into Egyptian antiquities. Subsequently, sometime between 1817 and 1821, an Italian explorer, Antonio Lebolo, uncovered a tomb near Thebes, Egypt, containing a large cache of mummies and papyri. Later, eleven of the mummies were sent to New York City under what remain curious circumstances. In early July 1835 some of the Saints in Kirtland Ohio, purchased four Lebolo mummies and some papyri from Michael Chandler, an antiquities dealer visiting the area. (Hauglid, Textual History of the Book of Abraham, 1.) JS’s close associate, William W. Phelps, provided the following account of these events to his wife: “On the last of June four Egyptian mummies were brought here. With them were two papyrus rolls, besides some other ancient Egyptian writings. . . . They were presented to President Smith. He soon knew what they were and said that the rolls of papyrus contained a sacred record kept by Joseph in Pharaoh’s court in Egypt and the teachings of Father Abraham.” Phelps added, “These records of old times when we translate and print them in a book will make a good witness for the Book of Mormon.” (William W. Phelps, Kirtland, OH, to Sally Phelps, Liberty, MO, 20 July 1835, in Journal History of the Church, 20 July 1835, CHL.)

Later that year, in response to public excitement prompted by “erroneous statements” circulating in the press concerning the Egyptian artifacts, correspondence between Oliver Cowdery, another close associate of JS, and a William Frye of Illinois was printed in the December 1835 issue of the Latter Day Saints’ Messenger and Advocate. Published under the heading “Egyptian Mummies—Ancient Records,” Cowdery’s letter to Frye endeavored to set the record straight concerning “a quantity of ancient records.” After reviewing the circumstances surrounding acquisition of the artifacts and describing some papyri in detail, Cowdery observed in closing, “When the translation of these valuable documents will be completed I am unable to say; neither can I give you a probable idea how large volumes they will make. . . . Be they little or much, it must be an inestimable acquisition to our present scriptures.” (“Egyptian Mummies—Ancient Records,” LDS Messenger and Advocate, Dec. 1835, 2:223−227.)

By the time the Messenger and Advocate account was published, JS, Cowdery, Phelps, and JS’s scribes Frederick G. Williams and Warren Parrish had invested portions of the previous six months working with the Egyptian material. JS’s journal for the period from October to December 1835 contains nine entries recording activity directly associated with the Egyptian documents. In addition, a JS history entry for July 1835, probably composed by William W. Phelps in 1843, notes that JS was “engaged in translating an alphabet to the Book of Abraham, and arranging a grammar of the Egyptian language as practiced by the ancients.” (JS, History, 1838–1856, vol. B-1, p. 597.)

The Egyptian manuscripts featured here, which constitute all the known and extant JS Egyptian manuscripts, range from a “counting” document to several “alphabet” documents to sheets of copied hieroglyphs. Scribes created entries on pages within a ledger book as well, titled “Grammar & Aphabet of the Egyptian Language.” In total, there is one ledger book, six other assorted records, and two small notebooks of copied hieroglyphs with English commentary. Some of the records are integral to one another; others are more textually tied to the papyri and extant manuscripts of the Book of Abraham. Historical introductions for each document will be posted soon to this website. For further information on the Abraham material, see “Introduction to Book of Abraham manuscripts.” The original papyri are partially extant; images are available here.

The Mummies of Nauvoo

by W. Ralph Odom Adapted from the diary of Solomon Hale

This is an adaptation from material found in the diary of Solomon Hale. He was a nephew of the Prophet Joseph Smith and lived in Nauvoo at the time the Prophet acquired the Egyptian mummies described in this incident.

As the nephew of Joseph Smith, I had access to the many mysteries of the then fabulous Nauvoo Mansion House. When I think of that place, and time, I remember a joke I was fond of playing on the children my age in our neighborhood.

Many people had heard of the “mummies” my uncle had in his study, but I don’t think too many knew for sure what or who they were. In some, superior knowledge breeds contempt, and my twisted sense of humor had a field day with the naive children of Nauvoo. You see, not only had I seen the mummies, but I also knew they were harmless.

I would gather four or five of my intended victims together in front of the Mansion House, with the promise that they would soon see the strange and bizarre sights of the upper floor. I told them they were about to go back in time to the land of the pyramids and savage demons, half lion and half man. My party and I would climb the stairs slowly so as not to disturb the slumbering spirits of the mummies and carefully enter the room where the treasures were.

I would arrange my trusting friends in a line facing the closet where the mummies were kept and, with all due reverence place my hand on the black drape hiding them from view.

I would count slowly to three, whisk the curtain aside. and watch with glee as my former friends would dash down the stairs in terror of the shriveled and dusty Egyptians.

Later I would meet them in the street with a self-contented and, I assure you, very smug smile. Once I brought down an old rag with me and chased them down Mulholland Street with it; I had told them it was the very piece of cloth used to cover the hearts of the mummies and could turn them into youthful reproductions of the monsters in the closet.

One day I found an especially dumb bunch of kids playing outside my uncle’s home. After my usual opening explanation, I led them into the Prophet’s study and began my act. I looked at them very carefully to impress upon them the miraculous thing they were about to behold. I had changed my act and had added what I felt sounded like an authentic Egyptian chant.

I finished the chant, pulled aside the drape, and was appalled by the lack of reaction; no one yelled or ran; the little girl present didn’t faint. Either my friends had amazing self-control or someone had done something to the mummies. They did, however, see something, for their mouths were opened so far their chins nearly touched the tops of their shoes. I looked around the corner of the closet and came face to face with my uncle’s watch bob.

There he stood, the Prophet Joseph, right where the mummies should have been. I looked for the telltale mark of the not-too-mad-adult, that amused-but-not-showing-it-over-the-childish-prank look, but it wasn’t there. So, giving him my toothiest smile, I ushered my audience out the door and down the stairs. That was the last time I ever went to see or ever wanted to see the mummies of Nauvoo. Source: https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/new-era/1973/12/the-mummies-of-nauvoo?lang=eng

Podcast: What Happened to the Mummies and Papyri Joseph Smith Purchased That Led to the Book of Abraham?

In this fascinating podcast from LDS Perspectives, Dr. John Gee sheds interesting light on some of the biggest mysteries associated with the Book of Abraham and its translation.

Having studied the topic for 30 years, he shares intriguing details of Joseph Smith’s purchase of the papyri that the Book of Abraham was translated from as well as the Church’s acquisition of fragments of the same papyri in the late 1960s.

An interesting part of the history of these papyri and the mummies acquired with them is that “Joseph [Smith] gave them to his mom and let her show them to people for 25 cents,” Dr. Gee shares. He continues, “It was a way of providing her with an income” after Joseph Smith Sr. passed away.

After Lucy Mack Smith died, Emma Smith sold the mummies and papyri, in part because Dr. Gee is convinced she was “sick of having dead bodies laying around the house.”

Dr. John Gee shares more about this topic in the book A Reason for Faith, which also includes other articles by experts that explain confusing or controversial aspects of Church history.

Lead image from Wikimedia Commons of a portion of the papyri used by Joseph Smith as the source of the Book of Abraham.

Part 2: Mummies in North America

A CATACOMB OF MUMMIES FOUND IN KENTUCKY

Lexington, in Kentucky, stands nearly on the site of an ancient town, which was of great extent and magnificence, as is amply evinced by the wide range of its circumvalliatory works, and the quantity of ground it once occupied.

Lexington, in Kentucky, stands nearly on the site of an ancient town, which was of great extent and magnificence, as is amply evinced by the wide range of its circumvalliatory works, and the quantity of ground it once occupied.

There was connected with the antiquities of this place, a catacomb, formed in the bowels of the limestone rock, about fifteen feet below the surface of the earth, adjacent to the town of Lexington. This grand object, so novel and extraordinary in this country, was discovered in 1775, by some of the first settlers, whose curiosity was excited by something remarkable in the character of the stones which covered the entrance to the cavern within. They removed these stones, and came to others of singular appearance for stones in a natural state; the removal of which laid open the mouth a cave, deep, gloomy, and terrific, as they supposed.

With augmented numbers, and provided with light, they descended and entered, without obstruction, a spacious apartment; the sides and extreme ends were formed into niches and compartments, and occupied by figures representing men. When alarm subsided, and the sentiment of dismay and surprise permitted further research and inquiry, the figures were found to be mummies, preserved by the art of embalming, to as great a state of perfection as was known among the ancient Egyptians, eighteen hundred years before the Christian era; which was about the time that the Israelites were in bondage in Egypt, when this art was in its perfection. * * * * * On this subject Mr. Ash has the following reflections: “How these bodies were embalmed, how long preserved, by what nations, and from what people descended, no opinion made, but what must result from speculative fancy and wild conjecture. For my part, I am lost in the deepest ignorance. My reading affords me no knowledge, my travels no light. I have neither read nor known of any of the North American Indians who formed catacombs for their dead, or who were acquainted with the art of preservation by embalming.

Had Mr. Ash in his researches consulted the Book of Mormon his problem would have been solved, and he would have found no difficulty in accounting for the mummies being found in the above mentioned case. The Book of Mormon gives an account of a number of the descendants of Israel coming to this continent; and it is well known that the art of embalming was known among the Hebrews, as well as among the Egyptians, although perhaps not so generally among the former, as among the latter people; and their method of embalming also might be different from that of the Egyptians.

Jacob and Joseph were no doubt, embalmed in the manner of the Egyptians, as they died in that country, Gen. 1, 2, 3, 26. When our Saviour [Savior] was crucified his hasty burial obliged them only to wrap his body in linen with a hundred pounds of myrrh, aloes, and similar spices, (part of the ingredients of embalming.) given by Nicodemus for that purpose: but Mary and other holy women had prepared ointment and spices for embalming it, Matt. xxviii. 59: Luke xxiii. 56: John xxx. 39-40.

Jacob and Joseph were no doubt, embalmed in the manner of the Egyptians, as they died in that country, Gen. 1, 2, 3, 26. When our Saviour [Savior] was crucified his hasty burial obliged them only to wrap his body in linen with a hundred pounds of myrrh, aloes, and similar spices, (part of the ingredients of embalming.) given by Nicodemus for that purpose: but Mary and other holy women had prepared ointment and spices for embalming it, Matt. xxviii. 59: Luke xxiii. 56: John xxx. 39-40.

This art was no doubt transmitted from Jerusalem to this continent, by the before mentioned emigrants, which accounts for the finding of the mummies, and at the same time is another strong evidence of the authenticity of the Book of Mormon.-[ED.

Source: Times and Seasons “Truth will prevail” Vol. III. No. 13] . CITY OF NAUVOO, ILL,. MAY 2, 1842 [Whole No. 49 Joseph Smith Editorializing from Ancient Antiquities Page 110-112 2 May 1842: Times and Seasons— Evidence from Kentucky

THE MOUND BUILDERS THEIR WORKS AND RELICS.

BY REV. STEPHEN D. FEET, PH. D., 1831-1914. VOL. I. ILLUSTRATED. CHICAGO: OFFICE OF THE AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN

https://archive.org/details/prehistoricameri01peetuoft/page/n453?q=indians+and+mounds

A shelter cave was discovered near San Jose, in California, by Dr. Stephen Bowers. It contained a number of baskets, in which were bundles of painted sticks, covered with peculiar signs, probably the outfit of a modern ”medicine man.” Caves have also been found in Utah, but as the remains of man were associated with ears of corn and other relics, we conclude that they were extremely modern. There were Cave-dwellers in the Mound-builders’ territory. Prof. Putnam has described several in Tennessee. There were mummies in one of these caves, dessicated bodies of natives which had been deposited, but which the salt had preserved, making them to resemble mummies. Some of these bodies were covered with feather headdresses and feathered robes and other equipments, resembling those used by later races. Page 10

A shelter cave was discovered near San Jose, in California, by Dr. Stephen Bowers. It contained a number of baskets, in which were bundles of painted sticks, covered with peculiar signs, probably the outfit of a modern ”medicine man.” Caves have also been found in Utah, but as the remains of man were associated with ears of corn and other relics, we conclude that they were extremely modern. There were Cave-dwellers in the Mound-builders’ territory. Prof. Putnam has described several in Tennessee. There were mummies in one of these caves, dessicated bodies of natives which had been deposited, but which the salt had preserved, making them to resemble mummies. Some of these bodies were covered with feather headdresses and feathered robes and other equipments, resembling those used by later races. Page 10

The part which the Mound-builders performed in connection with the neolithic age. The Mound builders, in a technical sense, are to be confined to the Mississippi Valley. There are, to be sure, many mounds and earth-works on the northwest coast, others in Utah, and still others scattered among the civilized races in Mexico, but the Mound-builders as such were the inhabitants of this valley. We shall see the extent of their territory if we take the mounds of the Red River Valley as one stream and follow the line across the different districts until we reach the mounds of Florida. This is the length of their territory north and south; the breadth could be indicated by the Allegheny mountains upon the east and the foot-hills of the Rocky mountains upon the west, for all this range of territory belonged to the Mound-builders.

Within this territory we have the copper mines of Lake Superior, 1 the salt mines of Illinois and Kentucky, 2 the garden beds of Michigan, 3 the pipe-stone quarries of Minnesota, 4 the extensive potteries of Missouri, 5 the stone graves of Illinois, 6 the work-shops, the stone cairns, the stone walls, the ancient roadways, and the old walled towns of Georgia, 7 the hut rings of Arkansas, 8 the shelter-caves of Ten nessee and Ohio, 9 the mica mines in South Carolina, 10 the quarries in Flint Ridge in Ohio, 11 the ancient hearths ot Ohio, 12 the bone beds 13 and alabaster caves in Indiana, 14 the shell-heaps of Florida, 15 oil wells and ancient mines, and the rock inscriptions 16 which are scattered over the territory everywhere.

We ascribe all of these to the Mound-builders and conclude that they were worked by this people, for the relics from the a rude people, whose remains are buried in the debris, for layers of ashes have been found having great depths. The fire beds and stone graves have been found at various depths beneath the river bottoms. Miami Gazette. Jan. 20, 1892. See Smithsonian Report, 1874. R. S. Robinson; Peabody Museum, 8th Report, F. W. Putnam. The Mammoth cave and other deep caves have yielded mummies and other remains which may have belonged to this antecedent period. Collins’ History of Kentucky. Page 36

BURIAL MOUNDS VIEWED AS MONUMENTS. DIFFERENT MODES OF BURIAL ASCRIBED TO DIFFERENT TRIBES OR RACES. Page 59

We propose in this chapter to take up the burial mounds in the United States and study them as monuments. The term is very appropriate, since they, in common with all other funereal structures, were evidently erected as monuments, which were sacred to the memory of the dead. Whatever we may say about them as works of architecture, they are certainly monumental in design. It is a singular fact that mounds have everywhere been erected for this purpose. We read in Homer that a mound was built over the grave of Patroclus, and that the memorial of this friend of Alneas was only a heap of earth. The name of Buddha, the great Egyptian divinity, has also been perpetuated in the same way. There are great topes, conical structures, in various parts of Asia, which contain nothing more than a fabled tooth of the great incarnate divinity of the East, but the outer surface of these topes is very imposing. The pyramids of Fgypt were erected for the same purpose. Some of them contain the mummies of the kings by whose orders they were erected. Some of them have empty tombs, and yet they are all monuments to the dead. It was a universal custom among the primitive races to erect such memorials to the dead. The custom continued, even when the races had passed out from their primitive condition, but was modified. The earth heaps gave place to stone structures, either menhirs or standing stones, cairns, cromlechs, dolmens, triliths. stone circles, and various other rude stone monuments, though all of these may have been more the tokens of the bronze age than of the stone age. We make this distinction between the ages: during the paleolithic age there were no burial heaps ; the bodies were placed in graves, or perished without burial. During the neolithic age the custom of burying in earth heaps was the most common, though it varied according to circumstances. During the bronze age stone monuments were the most numerous. When the iron age was introduced the the modern custom of erecting definite architectural structures appeared. The prevalence of the earthworks in the United States as burial places shows that the races were here in the stone age, but the difference between these will illustrate the different conditions through which the people passed during that age.

We propose in this chapter to take up the burial mounds in the United States and study them as monuments. The term is very appropriate, since they, in common with all other funereal structures, were evidently erected as monuments, which were sacred to the memory of the dead. Whatever we may say about them as works of architecture, they are certainly monumental in design. It is a singular fact that mounds have everywhere been erected for this purpose. We read in Homer that a mound was built over the grave of Patroclus, and that the memorial of this friend of Alneas was only a heap of earth. The name of Buddha, the great Egyptian divinity, has also been perpetuated in the same way. There are great topes, conical structures, in various parts of Asia, which contain nothing more than a fabled tooth of the great incarnate divinity of the East, but the outer surface of these topes is very imposing. The pyramids of Fgypt were erected for the same purpose. Some of them contain the mummies of the kings by whose orders they were erected. Some of them have empty tombs, and yet they are all monuments to the dead. It was a universal custom among the primitive races to erect such memorials to the dead. The custom continued, even when the races had passed out from their primitive condition, but was modified. The earth heaps gave place to stone structures, either menhirs or standing stones, cairns, cromlechs, dolmens, triliths. stone circles, and various other rude stone monuments, though all of these may have been more the tokens of the bronze age than of the stone age. We make this distinction between the ages: during the paleolithic age there were no burial heaps ; the bodies were placed in graves, or perished without burial. During the neolithic age the custom of burying in earth heaps was the most common, though it varied according to circumstances. During the bronze age stone monuments were the most numerous. When the iron age was introduced the the modern custom of erecting definite architectural structures appeared. The prevalence of the earthworks in the United States as burial places shows that the races were here in the stone age, but the difference between these will illustrate the different conditions through which the people passed during that age.

Incidentally, Colonel Bennett Young states that several mummies have been found in the caves in Kentucky encased in clothing. The cave which has yielded the most material of any which we have personally investigated is at Mills Spring in Wayne County about half-way between Burnside and Monticello. The cave is located on the farm of Hon. J. S. Hines and is known locally as the “Hines Cave.” This region is rather famous historically since it is adjacent to Price’s Meadow and Mills Spring where the “Long Hunters” who came to Kentucky from Virginia and North Carolina about 1770 are supposed to have camped for two years or more. Zollicoffer’s entrenchments are still visible across the Cumberland River.

The cave itself is extensive and is ideally situated for habitation. The land slopes from it gradually to the river, providing an excellent place for the cultivation of crops; the entrance to the cave is wide and high and the first chamber to which it leads is roomy and dry; the mouth is flanked by high cliffs which protect it from wind, rain and snow; the bottom is level and the light penetrates for a considerable distance from the entrance. Altogether it affords a shelter which must have been most desirable to a primitive race.

North America’s oldest mummy returned to US tribe after genome sequencing. DNA proves Native American roots of 10,600-year-old skeleton.

The sequencing of a 10,600-year-old genome has settled a lengthy legal dispute over who should own the oldest mummy in North America — and given scientists a rare insight into early inhabitants of the Americas.

The controversy centred on the ‘Spirit Cave Mummy’, a human skeleton unearthed in 1940 in northwest Nevada. The Fallon Paiute-Shoshone Tribe has long argued that it should be given the remains for reburial, whereas the US government opposed repatriation. Now, genetic analysis has proved that the skeleton is more closely related to contemporary Native Americans than to other global populations. The mummy was handed over to the tribe on 22 November.

The genome of the Spirit Cave Mummy is significant because it could help to reveal how ancient humans settled the Americas, says Jennifer Raff, an anthropological geneticist at the University of Kansas in Lawrence. “It’s been a quest for a lot of geneticists to understand what the earliest peoples here looked like,” she says. Source: https://www.nature.com/news/north-america-s-oldest-mummy-returned-to-us-tribe-after-genome-sequencing-1.21108#related-links

Related stories

- Lessons from the Ancient One

- Ancient American genome rekindles legal row

- Ancient genome stirs ethics debate

The case follows the US government’s decision this year that another controversial skeleton, an 8,500-year-old human known as Kennewick Man, is Native American and qualifies for repatriation on the basis of genome sequencing. Some researchers lament such decisions because the buried skeletons are then unavailable for scientific study. But others point out that science could benefit if Native American tribes use ancient DNA to secure the return of more remains, because this may deliver long-sought data on the peopling of the region. “At least we get the knowledge before the remains are put back in the ground,” says Steven Simms, an archaeologist at Utah State University in Logan, who has studied the Spirit Cave Mummy. “We’ve got a lot of material in this country that’s been repatriated and never will be available to science.”

EMINA is a searchable database of Egyptian mummy resources in North America, compiled by S.J. Wolfe (Mummies in Nineteenth Century America; Ancient Egyptians as Artifacts; McFarland, 2009) from thousands of digitized articles in newspapers, periodicals and books, as well as web sites, personal recollections, correspondences, and regular print resources.

http://www.egyptologyforum.org/EMINA/

The Spirit Cave Mummy is the oldest known mummy in the world. It was first discovered in 1940 by Sydney and Georgia Wheeler, a husband and wife archaeological team. The Spirit Cave Mummy was naturally preserved by the heat and aridity of the cave it was found in.

In 1997, the Paiute-Shoshone Tribe of Nevada’s Fallon Reservation enacted The Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) to claim the Spirit Cave Mummy’s remains. For nearly two decades the Paiute-Shoshone Tribe fought a legal battle against the U.S. government, who did not want to return the mummy. In 2016 the mummy was finally returned to the Paiute-Shoshone Tribe, after its DNA was sequenced to determine that he was related to contemporary Native Americans.

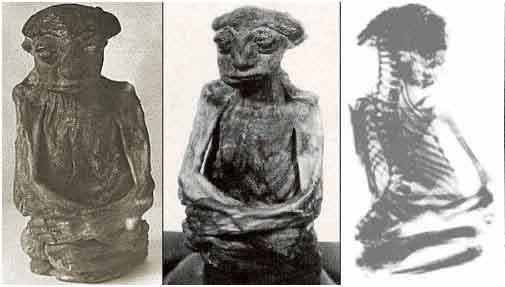

The mysterious Fawn Hoof Mummy: Ancient Egyptian Presence in North America

This fascinating mummy was found over 200 years ago in one of the largest cave systems in America: The Mammoth Cave. There, miners discovered an extremely well-preserved mummy with red hair prepared and embalmed in an eerily similar way as the ancient Egyptians. After examining the mummy in the late 1800’s, the Smithsonian Institute ‘lost’ the mummy.

Some 200 years ago, a very unusual mummy was discovered in Mammoth Cave, Kentucky.

There are a couple of things about the mummy which completely challenge what we have taught to believe about history books, especially about the ability and accomplishments of the Ancient Egyptians, their intrepid transoceanic voyages and their influence in other ancient cultures.

The mummy known as Fawn Hoof is considered by many as evidence that history books are wrong and that we are being given filtered information when it comes to ancient civilizations and the origins of mankind.

The mummy was mentioned in the book Prehistoric Mummies from the Mammoth Cave Area, by Angelo I. George where the author indicates that the mummy was found in the cave in September of 1811.

According to George, the Ancient mummy was given the name “Fawn Hoof” in 1815 and that ‘thousands’ of people saw the mummy as it was put on display. But what’s the story behind the mummy and why is it so important?

Sometime between Between 1811 and 1813 (different authors vary on the date, a group of miners were working inside one of the Kentucky caves known as Short Cave. One of the workers, who was excavating, came across a hard surface which proved to be a large rock with a flat surface.

After miners had removed the rock they discovered a crypt that contained a mummy inside. But it wasn’t an ordinary mummy. In the past, such discoveries were not given much importance and people looked to make a profit out of history.

In 1816, Nahum Ward from Ohio visited the cave, purchased numerous artifacts and the Fawn Hoof Mummy. In addition to the Fawn Hoof Mummy, Ward also purchased other mummies and some of them were over reportedly 2500 years old.

Years went by and the collection purchased by Ward was placed in a traveling exhibition of rarities. Through the years, the Fawn Hoof Mummy traveled across the country. It was first taken to Lexington, Kentucky and later transferred to the American Antiquarian Society.

Years went by and the collection purchased by Ward was placed in a traveling exhibition of rarities. Through the years, the Fawn Hoof Mummy traveled across the country. It was first taken to Lexington, Kentucky and later transferred to the American Antiquarian Society.

In 1876 the Fawn Hoof Mummy was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution by Isaiah Thomas, founder of the American Antiquarian Society. Due to the fact that the mummy was inadequately cared for and because it was transported a lot, the mummy suffered damage.

Researchers at the Smithsonian examined the mummy, dissected it and reported their findings. At some point after that –like many other things that challenge history— the Fawn Hoof Mummy was completely lost. According to initial reports, the mummy was found to have been a woman of around six feet in height. The mummy was wrapped in deerskin, which in turn was decorated with leaf and vine patterns.

The mummy was found to be in an extremely well-preserved condition even though the mummy was not analyzed by researchers for over 60 years after it was initially found. Among the more unusual finding was the fact that this mummy-like other mummies found in Peru and Bolivia in recent times— had red hair.

It was concluded that the hair was cut to a length of an eighth of an inch, except for the back of the mummy’s head where the hair was about two inches long. Based on the artifacts found where the mummy was buried, it is believed that the woman was of great importance in ancient times.

However, researchers noted that among the most fascinating details about the Fawn Hoof Mummy is the fact that it was prepared and embalmed in an eerily similar way as the ancient Egyptians used to. Reports indicate that the hands, ears, fingers, and the rest of the body were dried, but extremely well preserved.

But how is it possible that the mummy was lost? Is it possible that the mummy challenged historical doctrines set into place by certain institutions?

Many people believe that the Fawn Hoof Mummy is one of the many indicators which proves that thousands of years ago, before written history, ancient cultures around the globe were intricately connected and that transoceanic voyages occurred much sooner than mainstream scholars are willing to accept. https://www.ancient-code.com/the-mysterious-fawn-hoof-mummy-ancient-egyptian-presence-in-north-america/

Native American Nations

Mummies

In connection with cave burial, the subject of mummifying or embalming the dead may be taken up, as most specimens of the kind have generally been found in such repositories. It might be both interesting and instructive to search out and discuss the causes which have led many nations or tribes to adopt certain processes with a view to prevent that return to dust which all flesh must sooner or later experience, but the necessarily limited scope of this preliminary work precludes more than a brief mention of certain theories advanced by writers of note, and which relate to the ancient Egyptians. Possibly at the time the Indians of America sought to preserve their dead from decomposition some such ideas may have animated them, but on this point no definite information has been procured. In the final volume an effort will be made to trace out the origin of mummification among the Indians and aborigines of this continent.

In connection with cave burial, the subject of mummifying or embalming the dead may be taken up, as most specimens of the kind have generally been found in such repositories. It might be both interesting and instructive to search out and discuss the causes which have led many nations or tribes to adopt certain processes with a view to prevent that return to dust which all flesh must sooner or later experience, but the necessarily limited scope of this preliminary work precludes more than a brief mention of certain theories advanced by writers of note, and which relate to the ancient Egyptians. Possibly at the time the Indians of America sought to preserve their dead from decomposition some such ideas may have animated them, but on this point no definite information has been procured. In the final volume an effort will be made to trace out the origin of mummification among the Indians and aborigines of this continent.

The Egyptians embalmed, according to Cassien, because during the time of the annual inundation no interments could take place, but it is more than likely that this hypothesis is entirely fanciful. It is said by others they believed that so long as the body was preserved from corruption the soul remained in it. Herodotus states that it was to prevent bodies from becoming a prey to animal voracity. “They did not inter them,” says he, “for fear of their being eaten by worms; nor did they burn, considering fire as a ferocious beast, devouring everything which it touched.” According to Diodorus of Sicily, embalmment originated in filial piety and respect. De Maillet, however, in his tenth letter on Egypt, attributes it entirely to a religious belief insisted upon by the wise men and priests, who taught their disciples that after a certain number of cycles, of perhaps thirty or forty thousand years, the entire universe became as it was at birth, and the souls of the dead returned into the same bodies in which they had lived, provided that the body remained free from corruption, and that sacrifices were freely offered as oblations to the manes of the deceased. Considering the great care taken to preserve the dead, and the ponderously solid nature of their tombs, it is quite evident that this theory obtained many believers among the people. M. Gannal believes embalmment to have been suggested by the affectionate sentiments of our nature–a desire to preserve as long as possible the mortal remains of loved ones; but MM. Volney and Pariaet think it was intended to obviate, in hot climates especially, danger from pestilence, being primarily a cheap and simple process, elegance and luxury coming later; and the Count de Caylus states the idea of embalmment was derived from the finding of desiccated bodies which the burning sands of Egypt had hardened and preserved. Many other suppositions have arisen, but it is thought the few given above are sufficient to serve as an introduction to embalmment in North America.

From the statements of the older writers on North American Indians, it appears that mummifying was resorted to among certain tribes of Virginia, the Carolinas, and Florida, especially for people of distinction, the process in Virginia for the kings, according to Beverly, [Footnote: Hist. of Virginia, 1722, p 185] being as follows:

“The “Indians” are religious in preserving the Corpses of their Kings and Rulers after Death, which they order in the following manner: First, they neatly flay off the Skin as entire as they can, slitting it only in the Back; then they pick all the Flesh off from the Bones as clean as possible, leaving the Sinews fastened to the Bones, that they may preserve the Joints together: then they dry the Bones in the Sun, and put them into the Skin again, which in the mean time has been kept from drying or shrinking; when the Bones are placed right in the Skin, they nicely fill up the Vacuities, with a very fine white Sand. After this they sew up the Skin again, and the Body looks as if the Flesh had not been removed. They take care to keep the Skin from shrinking, by the help of a little Oil or Grease, which saves it also from Corruption. The Skin being thus prepar’d, they lay it in an apartment for that purpose, upon a large Shelf rais’d above the Floor. This Shelf is spread with Mats, for the Corpse to rest easy on, and skreened with the same, to keep it from the Dust. The Flesh they lay upon Hurdles in the Sun to dry, and when it is thoroughly dried, it is sewed up in a Basket, and set at the Feet of the Corpse, to which it belongs. In this place also they set up a “Quioccos,” or Idol, which they believe will be a Guard to the Corpse. Here Night and Day one or other of the Priests must give his Attendance, to take care of the dead Bodies. So great an Honour and Veneration have these ignorant and unpolisht People for their Princes even after they are dead.”

It should be added that, in the writer’s opinion, this account and others like it are somewhat apocryphal, and it has been copied and recopied a score of times.

According to Pinkerton [Footnote: Collection of Voyages, 1812, vol. XIII, p 39.], the Werowanco preserved their dead as follows:

“By him is commonly the sepulcher of their Kings. Their bodies are first bowelled, then dried upon hurdles till they be very dry, and so about the most of their joints and neck they hang bracelets, or chains of copper, pearl, and such like, as they used to wear. Their inwards they stuff with copper beads, hatchets, and such trash. Then lap they them very carefully in white skins, and so roll them in mats for their winding-sheets. And in the tomb, which is an arch made of mats, they lay them orderly. What remained of this kind of wealth their Kings have, they set at their feet in baskets. These temples and bodies are kept by their priests.

“For their ordinary burials, they dig a deep hole in the earth with sharp stakes, and the corpse being lapped in skins and mats with their jewels they lay them upon sticks in the ground, and so cover them with earth. The burial ended, the women being painted all their faces with black coal and oil do sit twenty-four hours in the houses mourning and lamenting by turns with such yelling and howling as may express their great passions.

“Upon the top of certain red sandy hills in the woods there are three great houses filled with images of their Kings and devils and tombs of their predecessors. Those houses are near sixty feet in length, built harbor wise after their building. This place they count so holy as that but the priests and Kings dare come into them; nor the savages dare not go up the river in boats by it, but they solemnly cast some piece of copper, white beads, or pocones into the river for fear their Okee should be offended and revenged of them.

“They think that their Werowances and priests which they also esteem quiyoughcosughs, when they are dead do go beyond the mountains towards the setting of the sun, and ever remain there in form of their Okee, with their heads painted red with oil and pocones, finely trimmed with feathers, and shall have beads, hatchets, copper, and tobacco, doing nothing but dance and sing with all their predecessors. But the common people they suppose shall not live after death, but rot in their graves like dead dogs.”

The remark regarding truthfulness will apply to this account in common with the former.

The Congaree or Santee Indians of South Carolina, according to Lawson, used a process of partial embalmment, as will be seen from the subjoined extract from Schoolcraft; [Footnote: Hist. Indian Tribes of the United States, 1854, Part IV, p. 155, et seq] but instead of laying away the remains in caves, placed them in boxes supported above the ground by crotched sticks.

“The manner of their interment is thus: A mole or pyramid of earth is raised, the mould thereof being worked very smooth and even, sometimes higher or lower, according to the dignity of the person whose monument it is. On the top thereof is an umbrella, made ridgeways, like the roof of a house. This is supported by nine stakes or small posts, the grave being about 6 or 8 feet in length and 4 feet in breadth, about which is hung gourds, feathers, and other such like trophies, placed there by the dead man’s relations in respect to him in the grave. The other parts of the funeral rites are thus: As soon as the party is dead they lay the corpse upon a piece of bark in the sun, seasoning or embalming it with a small root beaten to powder, which looks as red as vermilion; the same is mixed with bear’s oil to beautify the hair. After the carcass has laid a day or two in the sun they remove it and lay it upon crotches cut on purpose for the support thereof from the earth then they anoint it all over with the aforementioned ingredients of the powder of this root and bear’s oil. When it is so done they cover it over very exactly with the bark of the pine or cypress tree to prevent any rain to fall upon it, sweeping the ground very clean all about it. Some of his nearest of kin brings all the temporal estate he was possessed of at his death, as guns, bows and arrows, beads, feathers, match coat etc. This relation is the chief mourner, being clad in moss, with a stick in his hand, keeping a mournful ditty for three or four days, his face being black with the smoke of pitch pine mixed with bear’s oil. All the while he tells the dead mans relations and the rest of the spectators who that dead person was, and of the great feats performed in his lifetime, all that he speaks tending to the praise of the defunct. As soon as the flesh grows mellow and will cleave from the bone they get it off and burn it, making the bones very clean then anoint them with the ingredients aforesaid, wrapping up the skull (very carefully) in a cloth artificially woven of opossum’s hair. The bones they carefully preserve in a wooden box, every year oiling and cleansing them. By these means they preserve them for many ages that you may see an Indian in possession of the bones of his grandfather or some of his relations of a longer antiquity. They have other sorts of tombs as when an Indian is slain in, that very place they make a heap of stones (or sticks where stones are not to be found), to this memorial every Indian that passes by adds a stone to augment the heap in respect to the deceased hero. The Indians make a roof of light wood or pitch pine over the graves of the more distinguished, covering it with bark and then with earth leaving the body thus in a subterranean vault until the flesh quits the bones. The bones are then taken up, cleaned, jointed, clad in white dressed deer skins, and laid away in the “Quiogozon,” which is the royal tomb or burial place of their kings and war captains, being a more magnificent cabin reared at the public expense. This Quiogozon is an object of veneration, in which the writer says he has known the king, old men, and conjurers to spend several days with their idols and dead kings, and into which he could never gain admittance.”