How can you and I help the Lamanites? How can we help them blossom as the rose? When will their time actually be here where they assist us in building the New Jerusalem? I love them. I feel a kinship to them just as I have always felt about the Jewish people. Today I have never felt a stronger knowledge to know their plights are similar as they are the same people.

Bruce R. McConkie was asked the question, “What did Jacob mean when he said that the Jews would be restored ‘to the land of their inheritance’? (see 2 Nephi. 9:2). He answered, “The Lamanites are Jews, aren’t they? (MLM Journal, Dec. 6, 1984).

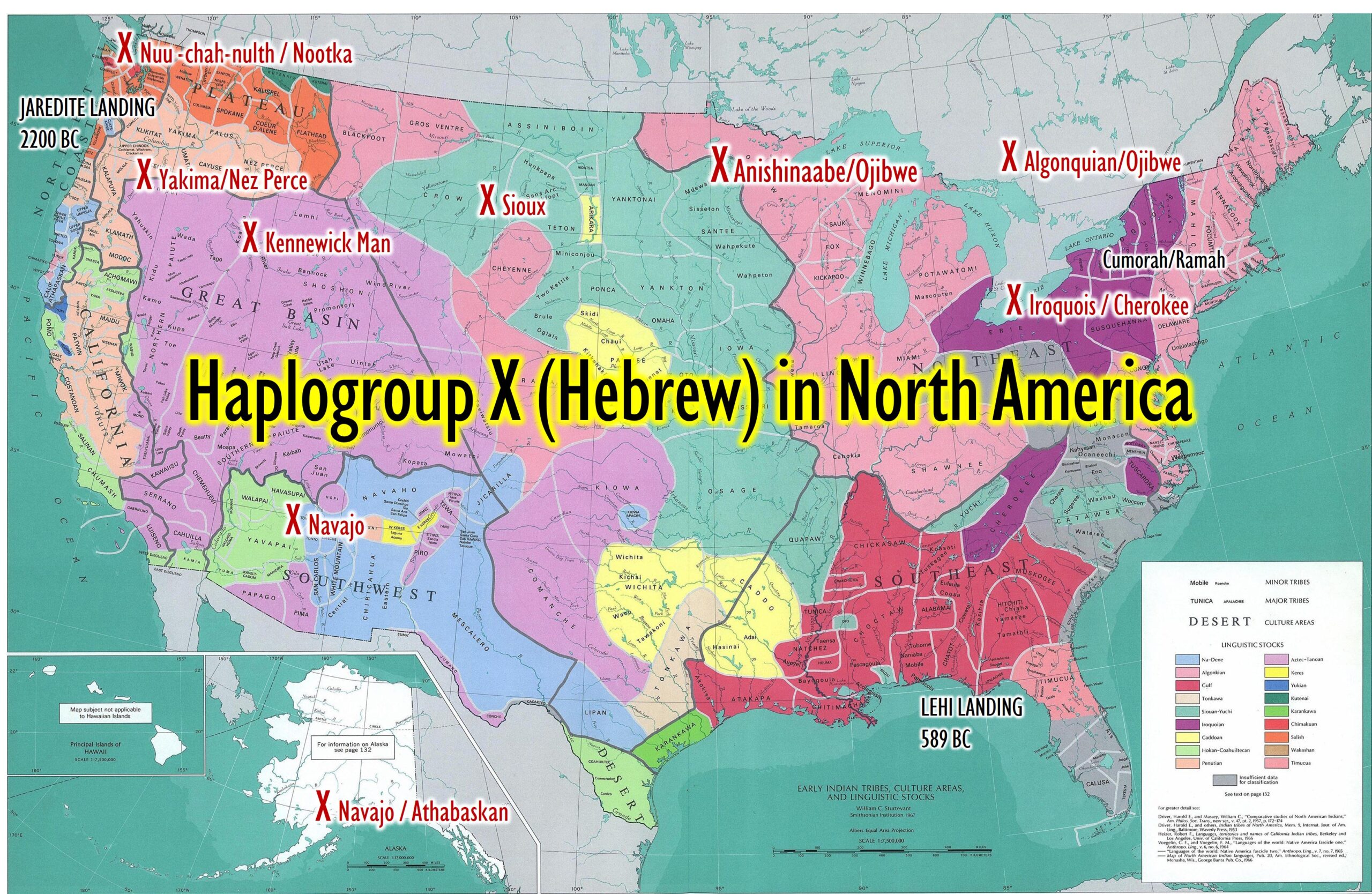

Please let that sink into your heart. The Jews and the Native Americans specifically the Iroquois and Algonquin of the United States, are one in the same (See DNA blog here). We remember the first shall be last and the last shall be first in receiving the gospel. The day of the Gentile is slowing down. Let us seek to love and help the Lamanites.

I have enjoyed a strong love of the Catawba Nation of Lamanites in the past 3 years or more. I would like to share with you an inspiring story about Chief Samuel Blue and his family. The Mormon Catawba’s of 1890 flourished and the Mormon Catawba’s of today are struggling as many of the wonderful Lamanites of North America are. At one point in 1840 there were only 110 of the Catawba Nation and today there are still only 2,600. Where have they gone and what is our responsibility as Gentiles to bring the Gospel to them? I pray this blog will inspire you to reach out and help these wonderful people. Their faith will amaze you.

Power to Forgive by Chief Blue

“One day my eleven-year old son went hunting with six other Indians. They were hunting squirrels. A squirrel darted up a pine tree and my son climbed up the tree to scare him out on a limb. Finally, the squirrel ran out where he could be seen. My boy called to the hunters to hold their fire until he could get down out of the tree. One of these Indians in the hunting party had always been jealous of me and my position as chief. He and his son both shot deliberately at my boy. He was filled with buckshot from his knees to his head. One blast was aimed at his groin and the other hit him squarely in the face. The Indians carried my boy toward our home and found a cool spot along the trail under a pine tree. There they laid him down and ran for a doctor.

“A friend came to me in Rock Hill where I had gone to buy goods and said, “Sam, run home at once, your boy has been shot.’ I thought it was one of my married sons. I ran all the way home and found that it was my little boy near death. The doctor was there. He had put the boy to sleep with morphine, so he wouldn’t be in so much pain. He said my boy could not live. He was right; the boy died in a few minutes.

“The man and his son who had done the shooting were out in my front yard visiting with members of the crowd that had gathered. They did not appear to be upset at their deed. My heart filled with revenge and hatred… Something seemed to whisper to me, ‘If you don’t take down your gun and kill that man who murdered your son, Sam Blue, you are a coward.’

“Now I had been a Mormon ever since I was a young lad, and I knew it would not be right to take revenge. I decided to pray to the Lord about it. I left the house and walked to my secret place out in the timber where I always have gone to pray alone when I have a special problem, and there I prayed to the Lord to take revenge out of my heart. I soon felt better, and I started back to my place of prayer and prayed again until I felt better. Then on my way back to the house, at the same spot along the path I heard the voice say again, ‘Sam Blue, you are a coward.’ I turned again and went back to pray. This time I told the Lord He must help me or I would be a killer. I asked Him to take revenge out of my heart and keep it out. I felt good when I got up from praying. I went back to the house the third time and when I reached the house I went out and shook hands with the Indian who killed my boy – there was no hatred or desire for revenge in my heart.”

(Quoted in Marion G. Romney, The Power of God unto Salvation, Brigham Young University Speeches of the Year [Provo, Utah. 3 Feb. 1960], pp. 6-7) Transcribed by Rian Nelson July 24, 2018 from Knowing Christ by George W. Pace (Joseph Harvey Blue b.03-14-1903 d.01-08-1914 of a gunshot wound. Source

www.findagrave.com/memorial/112939391/samuel-taylor-blue)

South Carolina Ward Celebrates History of the Gospel among the River People

Catawbas and Christ: A History of the Mormon Church among the River People came to fruition on April 28, 2018. Visitors participated in pottery making, tasted venison stew, and observed Indian dancing, music, and drumming by members of the tribe. The hallways of the Church building were lined with photos and historical accounts written by tribal, family, and ward members with the help of Elder Michael and Sister Karren Boone, from the North Carolina Charlotte Mission. Tribal quilts and artifacts were on display in various classrooms.

Article August 8, 2018 Read Here

Catawba Indian Genealogy by Ian Watson The Geneseo Foundation and the Department of Anthropology, State University of New York at Geneseo 1995

Catawba Genealogy Here

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in South Carolina

“The first LDS member in South Carolina is believed to be Emmanual Masters Murphy, who was baptized in Tennessee in 1836. When Elder Lysander M. Davis arrived in South Carolina in 1839 (nine years after the Church was organized in New York), he found the Murphys had people prepared for baptism. Seven of these were baptized.

“The first LDS member in South Carolina is believed to be Emmanual Masters Murphy, who was baptized in Tennessee in 1836. When Elder Lysander M. Davis arrived in South Carolina in 1839 (nine years after the Church was organized in New York), he found the Murphys had people prepared for baptism. Seven of these were baptized.

Opposition arose and Davis was briefly jailed. Murphy had reportedly spoken with Church President Joseph Smith in the late 1830s, and was told to warn South Carolinians of the destruction soon to hit their state, “the wars that will shortly come to pass, beginning at the rebellion of South Carolina, which will eventually terminate in the death and misery of many souls … the Southern states will call on other nations, even the nation of Great Britain…” This warning saw reality in 1861, when the Confederates attacked Fort Sumter, and the Civil War commenced.

Catawba tribe

The South Carolina Conference was organized on March 31, 1882, with its first president as Elder Willard C. Burton of the Southern States Mission. (Southern States Mission History 1832-1880) The Kings Mountain Baptist Church had several families convert on March 12, 1882. Some of the earliest branches were established at King’s Mountains beginning March 3, 1882, and among the Catawba Indian community beginning July 31, 1885. Conference headquarters were established at the plantation of John Shaw Black, a man who remained unbaptized in order to provide refuge for the Church, and a veteran of the Palmetto Sharpshooters. Many converts, including Indians, moved onto his plantation to escape persecution. The Catawbas also shielded missionaries from persecutions. Two families were noted in Missionary journals as being home base, James and Elizabeth W Patterson’s home shielded them on the occasions of the mobs hunting them. Evan and Lucy Marsh Watts were the host family when Elder C E Robinson died, and they were again helping when the two Elders were injured, Elder W C Cragun and F A Franughton. Most of the Catawbas joined the Church and remained faithful in South Carolina.

One of the more known LDS members of the Catawba tribe was Samuel Taylor Blue (Chief Blue). Blue was baptized in 1897. A few years later he served as branch president of the branch of the LDS Church on the Catawba Reservation. In the early 20th century he would often help missionaries escape mobs. In 1950 Blue traveled to Salt Lake City and gave a talk at General Conference on April 9. (Full Article at the end of this post)

Another Catawba, the first Lamanite Patriarch, William F Canty came from 5 families who moved west with the Migration in 1887. His father John Alonzo Canty was the first Branch President of the Gaffney area, and James Patterson, his grandfather was the first Branch President of the Catawba Branch. William (Buck) Canty spoke at the BYU Indian school graduation many times in the 1970s and toured with the Lamanite Generation in 1978.

Another Catawba, the first Lamanite Patriarch, William F Canty came from 5 families who moved west with the Migration in 1887. His father John Alonzo Canty was the first Branch President of the Gaffney area, and James Patterson, his grandfather was the first Branch President of the Catawba Branch. William (Buck) Canty spoke at the BYU Indian school graduation many times in the 1970s and toured with the Lamanite Generation in 1978.

Genealogy of the Western Catawba, Missionary Journals of Joseph P Willey and Pinkney Head, and My Father’s people, all written by Judy Canty Martin. News articles from the Church news in 1978 and other sources of family.

Church growth

Progress and persecution continued in the 1890s. Mobs often gathered to persecuted missionaries. In 1897, mobs burned one of South Carolina’s first Latter-day Saint meetinghouses in ab area called by locals Centerville near the small town of Ridgeway South Carolina. It was rebuilt and burned again in 1899.

Branches organized included Society Hill, Columbia, Charleston, and Fairfield. However, as converts migrated to the West, branches dwindled, and some were reorganized later with new converts. The South Carolina conference included six branches (four with meetinghouses) and 10 Sunday Schools.

On November 20–21, 2004, President Hinckley spoke to nearly 12,000 Church members in Columbia, S.C., with proceedings carried to 11 meetinghouses in 11 other stakes in South Carolina and Georgia.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in South Carolina

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

BOOK OF MORMON PROMISES TO INDIANS COMING TRUE, SAYS CHIEF. —

“One of the most colorful figures among the Latter-day Saints is Chief Samuel “Thunderbird” Blue, 82- year-old former chief of the Catawba Indians of South Carolina.

“One of the most colorful figures among the Latter-day Saints is Chief Samuel “Thunderbird” Blue, 82- year-old former chief of the Catawba Indians of South Carolina.

His tribe is located on a reservation near Rockhill, South Carolina, and more than 90 per cent, of them are Latter-day Saints. They have a new chapel which was dedicated there two years ago by President McKay. Chief Blue, one of the oldest members of the Church among the Catawbas, spoke at those dedicatory services. He paid a visit to Salt Lake City in 1948, having the privilege of speaking from the pulpit of the Salt Lake Tabernacle.

He and his wife were the first of their tribe to go through a Mormon temple. This they did when they were in Salt Lake City. Missionaries first came to the Catawbas about 70 years ago.

Then there were only about 100 of these Indians. Now there are over 400.

Chief Blue said that the “Book of Mormon promise to the Indians is coming true and that the younger generation of Indians are now very light.” Cumorah’s Southern Messenger June, 1954 Ezra Taft Benson

ELDER CHIEF SAMUEL BLUE GENERAL CONFERENCE Sunday, April 9, 1950

“Brethren and sisters, we are told that the Lord moves in mysterious ways, and I bear testimony this is true. It is wonderful to me that I have this privilege to enter this building and attend this conference.

I have been a member of the Church, as you have been told, for sixty-odd years. I am one of the poor Indians down there on the reservation, and as we were told a while ago, “Seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you.” I surely bear testimony to this.

I was raised up as a poor boy, as I said before, and worked at 25 cents a day I fed my mother, brothers and sisters, and when I was fifteen years old, the missionaries came to my home and I have fed the Elders off my wages. I slept out in the woods to give my bed to the Elders. I have wondered to myself, how would I get through this world, but nevertheless, I seek to do the will of God. I fasted and prayed unto him for a blessing, and we have been told if we seek God, other things will be added unto us, and this is one of the “adds” that have been given to me. I am thankful for those blessings.

I have lived at home with two missionaries in my house. They were boarding in Rock Hill. Their room was costing them fifteen dollars a week. I said: “Elders, come to my home. I have a cabin with a room in it you can use, with two beds in it”; so they have taken the room, they eat at my table, sleep under my roof. They want to pay me wages for staying there. I say: “No. The Lord has provided for me and he is providing for you. I want no pay.”

So when I left home the other day, Elder Price, he had a hundred dollars in his pocketbook. He offered me part of it. I said: “No, I don’t want it.” “Well,” he said, “you made it for me.” I said: “How did I make it?” ”

You did not charge me for my bedroom or for food, and by so doing I have been able to accumulate this much which my parents have sent to me.” I said: “If I have done you that much good by the will of God, keep it and use it in your mission.”

I know that this gospel is true. I have tasted the blessing and joy of God. I have seen the dead raised; I have seen the sick whom the doctors have given up, through the administration of the Elders they have been restored to life.

My brothers and sisters, beyond a shadow of a doubt I know that this gospel is true. My wife is with me and she is not very well, and I have not been feeling well either. She told me last night, we

had better go home. I said: “Why? I have come here for a good purpose, and if I die here I would just as leave die here as in the world till I have filled the obligation that I am sent here to do. Now may God bless you, Amen.” Elder Chief Blue

President David O. McKay responded below:

“You have just had the unusual experience of hearing from one of our Indian members from the Catawba Tribe, Elder Chief Blue. President George Albert Smith will now make a few comments upon that and such other comments as he will wish to make.”

PRESIDENT GEORGE ALBERT SMITH response below:

“When I was twenty-one years of age, I was sent on a mission to the southern states. I became secretary of the mission, and while there was called to Columbia, South Carolina, because some of our elders had become seriously ill. It was difficult to get word back and forth, so I got on a train and went down there. I found that they were improved and getting along all right.

“When I was twenty-one years of age, I was sent on a mission to the southern states. I became secretary of the mission, and while there was called to Columbia, South Carolina, because some of our elders had become seriously ill. It was difficult to get word back and forth, so I got on a train and went down there. I found that they were improved and getting along all right.

Missionary Experience

When I bade them good-bye, I boarded the train and started home, and we passed a little Indian settlement at the side of the track. I saw evidence that there were quite a number of Indians here, so I reached over and touched the man who was sitting in the seat in front of me, and I said, “Do you know what Indians these are?”

He said, “They are the Catawbas.” That is the tribe that Chief Blue represents, who has just spoken to us. I asked, “Do you know where they come from?” He said, “Do you mean the Catawbas?” I replied, “Any Indians.”

He said, “Nobody knows where the Indians came from.”

“Oh,” I said, “yes they do.” I was talking then to a man about forty-five or fifty years old, and I was twenty-one. He questioned, “Well, where did they come from?”

I answered, “They came from Jerusalem six hundred years before the birth of Christ.” “Where did you get that information?” he asked. I told him, “From the history of the Indians.” “Why,” he said, “I didn’t know there was any history of the Indians.”

I said, “Yes, there is a history of the Indians. It tells all about them.” Then he looked at me as much as to say: My, you are trying to put one over on me. But he said, “Where is this history?”

“Would you like to see one?” I asked. And he said that he certainly would. I reached down under the seat in my little log- cabin grip and took out a Book of Mormon and handed it to him.

He exclaimed, “My goodness, what is this?” I replied, “That is the history of the ancestry of the American Indian.” He said, “I never heard of it before. May I see it?”

I said, “Yes” and after he had looked at it a few minutes, he turned around to me and asked, “Won’t you sell me this book? I don’t want to lose the privilege of reading it through.”

“Well,” I said, “I will be on the train for three hours. You can read it for that long, and it won’t cost you anything.” I had found that he was getting off farther on, but I had to get off in three hours.

In a little while he turned around again and said, “I don’t want to give up this book. I’ve never seen anything like this before.”

I could see that he apparently was a refined and well-educated man. I didn’t tell him I really wanted him to read the book, but I said, “Well, I can’t sell it to you. It is the only one I have.” (I didn’t tell him I could get as many more as I wanted.)

He said, “I think you ought to sell it to me.”

I replied, “No, I’ll tell you what I’ll do. You keep it for three weeks, and at the end of that time you send it to me at Chattanooga,” and I gave him my card with my address on, secretary of the mission.

So we bade one another good-bye, and in about two weeks he wrote me a letter saying, “I don’t want to give this book up. I am sure you can get another, and I will pay you any price you want for it.”

Then I had my opportunity. I wrote back, “If you really enjoy the book and have an idea it is truly worth while, accept it with my compliments.” I received a letter of thanks back from him.

I speak of that because that was the first time I had ever heard of the Catawba Indians, and there were only a few of them. I understand now from Chief Blue that ninety-seven percent of them are members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Meeting 15 Years Later

Coming back to this book again — Brother B. H. Roberts and I were sent some fifteen years later down into the southern states to visit the mission. When we arrived at the hotel at Columbia, we registered and went into our room, and soon after a knock came at the door and a colored man said, “There’s a man downstairs that wants to see George A. Smith.” That was the way I used to write my name, and I wrote it that way before I was married.

Coming back to this book again — Brother B. H. Roberts and I were sent some fifteen years later down into the southern states to visit the mission. When we arrived at the hotel at Columbia, we registered and went into our room, and soon after a knock came at the door and a colored man said, “There’s a man downstairs that wants to see George A. Smith.” That was the way I used to write my name, and I wrote it that way before I was married.

I said to Brother Roberts, “What will we do?” and he replied, “Send him up,” so the man went back, and pretty soon up came a man and knocked on the door, and we opened it.

He reached out his hand and said, “My, I am glad to see you.” I said, “I am glad if you’re glad to see me; I am happy to see you, but who are you?” and he gave me his name.

I asked, “What can I do for you?” He said, “Don’t you remember me?”

I told him, “Remember you? I don’t believe I ever saw you before.” He said, “Isn’t your name George A. Smith?” and I said, “Yes.”

“Well, he replied, “I am sure you’re the man. I met George A. Smith years ago as he was doing missionary work here.” I answered, “Oh, that is easily explained, there was another George A. Smith here doing missionary work, too.”

“Oh,” he said, “it wasn’t any other George A. Smith. It was you. Nobody that ever saw that face would forget it.” Well,” I said, “I guess I must be the man.”

Then he related this story. He said, “You were on a train, and we passed the Catawba Indian Reservation.” I interrupted, “I remember all about it now.” It all came back in an instant.

He said, “I want to tell you something. I read that book, and I was so impressed with it that I made up my mind I would like to take a trip down into Central America and South America, and I took that book with me in my bag when I went down there. As a result of reading it, I knew more about those people than they knew about themselves.

“I lost your address; I didn’t know how to find you, and all these years I wanted to see you, and today after you registered downstairs I happened to be looking at the hotel register and I saw your name. That is how I found you.

“I am a representative of the Associated Press for this part of the United States. I understand you are here in the interest of your people.” – – And I answered, “Yes, Mr. Roberts and I both are here for that purpose,”

And he said, “If there is anything I can do for you while you are here, if you want anything put in the press, give it to me and it won’t cost you a cent. But,” he continued, “I want to tell you one other thing, I have kept your missionaries out of jail; I have got them free from mobs; I have helped them every way I could; but I have never been able to get your address until now.”

Chief Blue and Catawba Indians

So you may be interested, brethren and sisters, in knowing that I am delighted in seeing Chief Blue here today, representing that tribe of fine Indians. I have seen some of them since. I have met one very fine young woman who is a schoolteacher, and others I have met of that race; in fact, I have some trinkets in my office that were sent to me by members of that tribe.

So you may be interested, brethren and sisters, in knowing that I am delighted in seeing Chief Blue here today, representing that tribe of fine Indians. I have seen some of them since. I have met one very fine young woman who is a schoolteacher, and others I have met of that race; in fact, I have some trinkets in my office that were sent to me by members of that tribe.

I am happy to have this good man here who represents one of the tribes that descended from Father Lehi as well as some of the others that are in our audience today. One good man that I am looking at here came to the temple during the week and was sealed to his wife. They are coming into the Church all around, and I am so grateful this morning to be here and hear this man who for sixty years has been a faithful leader among his people and now comes to this general conference and bears testimony to us.

It is a great work that we are identified with. Not the least of our responsibilities is to see that this message is carried to the descendants of Lehi, wherever they are, and give them an opportunity to accept the gospel of Jesus Christ.

Additional Knowledge

How glorious it is to know that we have that information, and we have the knowledge that there were others resurrected, as recorded in the New Testament. And then we have the information in the Book of Mormon of the coming of the Savior to this western hemisphere, and we have the appearance of John the Baptist, and Peter, James, and John, and the Father and the Son to Joseph Smith in these latter days. No other people have what we have. I don’t know of any people who ought to be so anxious and willing and grateful to be able to celebrate this day that is recognized in the world as the anniversary of the resurrection of the Redeemer of mankind, and that meant the opening of the grave for all humanity.

I pray the Lord to bless us that we may be worthy because of our lives to keep this testimony, that not only we, but all we can reach may receive that witness and carry it to our brothers and sisters of all races and creeds, and particularly to the descendants of Lehi, until we have done our duty by them. I am sure that when the time comes for the resurrection, that all who are in their tombs and worthy shall be raised from their graves, and this earth shall become the celestial kingdom, and Jesus Christ, our Lord, will be our King and our Lawgiver — that we will rejoice that we have availed ourselves of the truth and applied it in our lives. That is what the gospel teaches us. That is what the gospel offers to us if we will accept it, and I pray that we may be worthy of it in the name of Jesus Christ. Amen.

Chief Samuel Taylor Blue

“For many Catawba people, Chief Samuel Taylor Blue (c.1872-1959)—often referred to as Chief Sam Blue or simply as Chief Blue—looms large as a symbol of the relationship between the Catawba Nation and the Mormon Church. So large, in fact, that some people I have talked to remembered him as being chief at the time the first Mormon missionaries came—an impressive feat since he would have been about ten years old at the time. But he was old enough to remember when the first missionaries came and he reportedly told stories about helping missionaries sneak in and out of the nation when he was a child and young man. One church publication recalled that “during the days of persecution, he had carried the missionaries across the river on his back to protect them from the mobs.”71

Blue became chief of the Catawba Nation in the early 1930s and served during most of that decade and intermittently in that capacity several times over the course of his life.72 He also served as president of the Catawba Branch and as a respected elder and leader both in the church and the Catawba nation, which were not easily distinguishable to many. While he has not always been regarded in quite the same light by all nation members, he is probably the most prominent single figure in the history of the modern Catawba Nation and is highly esteemed by his descendants and many other nation members to this day. He was also quite well known outside of the Catawba Nation among the local community and in the church, and continues to be to a significant extent. This is particularly true in the LDS Church. In 1950 he and his wife Louisa traveled to Salt Lake City to attend General Conference and to be sealed in the temple. While there Blue was spontaneously called upon to speak in the conference before the general body of the church—an event that is not only remembered but still held in digital copy by some of his descendants. During my fieldwork I watched a recording of Chief Blue’s talk at the home of Travis Blue, a great grandson.

A good example of Chief Blue’s legacy among his descendants and in the LDS Church is the way his great-great grandson, Matt Burris , describes him. “When it comes to the tribe and the church,” Burris explained, “I always think of him…because he was a very good example, as a member of the church and a member of the tribe.” In Burris’s memory of the Catawba past, from the stories he’s been told, the years that his great-great grandfather served as chief were something like a golden era of Catawba history. “During his time he was chief, ninety-nine or even a hundred percent of the tribe were members of the church…. and at the time,” Burris shared his opinion, “there was kind of a big happiness in the tribe, there weren’t any problems or things like that.” Burris tied this period of perfect church attendance to a scripture in the book of Enos in the Book of Mormon about the Lamanite people: “there was a promise that if they obeyed the commandments they would blossom like a rose into a beautiful—beautiful people. And…at the time when my great-great grandpa was chief, the people were following the commandments and doing what they were supposed to, and they were a beautiful people.” Burris contrasted this with the present. “Now, very sadly, it’s the opposite. The majority of the tribe aren’t members, and if they are members they don’t come to church. There’s a very big problem with inactive members in the tribe right now.” Burris also seemed to imply that the tribe is also politically less united than he imagines it was then. He spoke of conflicts and divisions within the tribe and of his own extended family’s withdrawal from politics after his grandfather and other relatives resigned from their positions in tribal leadership. While several members of the Blue family have withdrawn from formal politics, they remain active in the LDS Church and find family solidarity there.

Burris in fact carried his great-great grandfather’s legacy with him on his LDS mission to Chile. He also found that, much to his surprise, parts of that legacy were already there, and he also, quite literally, carried part of it back home with him. There is a story about Chief Blue that has achieved some level of prominence and familiarity among church members by being included in a number of church publications.73 Burris carried a copy of the story with him on his mission and used it in his teachings, only to discover that his mission president was already familiar with it. Burris described feeling shocked that this man who had spent his entire life in Argentina had heard of Catawbas and of Chief Blue. The mission president had the story translated into Spanish, distributed it to the mission, and referred to it in his talks. Thus, Chief Blue and Catawba Mormonism became part of the Mormon missionary curriculum in Chile. Further, Burris described connecting with Indigenous peoples in Chile when they discovered that he was Native American; he said that many Chileans, particularly those of the Mapuche tribe, identified as Lamanites, an Indigenous Mormon identity that also linked them, since Burris identifies the Catawba people as Lamanites. Before leaving the mission he had a special leather case made for his scriptures with two images burned into it, based on prints he had brought with him. On one side is a depiction of the Book of Mormon character Enos, known for his long and soul-wrenching prayer for the descendants of the Lamanite people. On the other side is, of course, an image of his great-great grandfather, Chief Blue. Thus, holding together his scriptures, like two bookends, is a Nephite prophet praying for the welfare of the future Lamanites, and the latter-day Lamanite Catawba Chief Samuel Taylor Blue, quite literally now a part of the Book of Mormon, burned into the cover of his great-great grandson’s missionary scriptures.

Catawba “Pride Cycle”: Reading Catawba History through the Book of Mormon

A cycle emerges from the Book of Mormon that has become popularly known as “the pride cycle.” Though that phrase does not appear in the Book of Mormon, it was popularized through a church video made in 1995 and shown as part of the standard curriculum in church seminary and Sunday School classes, and probably predates that. It has become part of the standard Mormon parlance. A diagram illustrating this cycle, published as an appendix to the church-produced Book of Mormon Student Manual, reveals five stages of that cycle: 1. blessings and prosperity are followed by 2. pride and wickedness which leads to 3. warning by prophecy which, when rejected, leads to 4. destruction and suffering, resulting in 5. humility and repentance, which leads back to number one. The manual describes this as “a recurring cycle that underlies the rise and fall of nations as well as individuals,” revealed by the Book of Mormon. Ultimately, as the Book of Mormon teaches, it was pride—like hubris, the tragic flaw of the classic Greek hero—that led to the overthrow of the Nephites, a fact reiterated by Joseph Smith’s later revelations and by more recent prophets who quote the warning: “beware of pride, lest ye become as the Nephites of old.”74

I have talked to more than one Catawba person who felt they could see a “pride cycle” at play in the history of the Catawba people. For example, Kathryn Ellis explained that her father felt that when you see the pride cycle that’s referred to in the Book of Mormon, of people getting closer to Heavenly Father when things are maybe not going so great, and then when things do start going well then they allow themselves to have other influences enter in because they feel like things are going well now—he really likened that to the tribe and how, through the ups and downs of the tribe, throughout its history, there were times when things weren’t going well and the people really pulled together and came closer to heavenly father and closer to the church, had more attending church and a better feeling at church; and then when things were going well, then other things entered in like jealousy and money and greed, and it affected how people lived their lives and it affected the spirituality of the people as a whole, and some even fell away from church because of things they saw other church members doing within the tribe. The tribal government itself. So he always felt like the history of the church correlated. Or he could see a lot of that pride cycle in the people here.

Ellis was hesitant to say she saw that cycle clearly at play, explaining that it is harder to really pin down now because there are a lot of tribal members attending other churches, if they even attend church. She identifies this as a fairly new development, even within her own life. As she explained, “it used to be a lot more centralized where…all the tribal members that were church members were all going to Catawba Ward, for the most part.” However, as more Latter-day Saints have moved into the surrounding area, wards and meetinghouses have proliferated and the geographical boundaries have shrunk. As more and more people have moved out from the reservation and immediate vicinity, it now means they attend different wards on those communities. The Catawba Ward has also been split and is now attended by as many or more non-Catawbas as Catawbas. I have talked to a few Catawba people who used to attend and still recall those good old days when it was the entire Catawba community, and only them, that gathered on Sunday for meetings. Church meeting was a tribal gathering then. However, as the ward has split, non-tribal members have moved in, and many Catawba people have begun attending other wards, the de facto Catawba-Mormon congregation became fragmented, and as a result many stopped attending. When the church body no longer correlated with the tribal body, it seems to have lost its appeal for many Catawba people.

But if Ellis was hesitant to really impose the pride cycle onto Catawba history as a model with perfect explanatory force, she did identify the events surrounding the 1993 settlement as a moment when the pride cycle seemed to come into play, or had explanatory power for understanding that political climate. She explained that in the late 1970s “the tribe had kind of come together…especially the ones that felt they wanted to regain the federal recognition.” That was the period of struggle and unity. However, when they were successful, and “once we received the settlement in 1993, there was a lot of money that came with that.” And so, naturally, with prosperity there came divisions. “You have this group of people who kind of have control over this fifty million dollars, and how it’s spent, and then you have these people that are on the outside who think they know how the money should be spent or not spent, and it just…there became a lot of fighting between the two groups.” She explained that “there were people in both of those groups who were church members, so, it affected a lot of things, not just for the tribe but at church.” Some people stopped attending church. “So it really affected a lot of people, and from what I understand, it’s even caused some barriers for missionaries even until today, because…they’ll say, ‘Well, I’m not going there because so-and-so spent all the tribe’s money.’…after all these years, it’s still causing barriers to getting people to come back to church.” While she felt it’s still too early to tell if the settlement was a watershed moment for defining church affiliations in the tribe, she did state that “I do feel like it was a little bit of a turning point, from what I can see at this point in our history.”

I interviewed one other person who made reference to the pride cycle and other Book of Mormon references specifically in reference to tribal politics. “Every time around elections the pride gets way up here [reaches above his head]. Everybody’s better than everybody else. It’s sad…. It’s like you live among the Gadianton Robbers.” Even this he explained as a possible fulfillment of the Book of Mormon, which states “that there’s opposition in all things.” “Maybe that’s a part of the scriptures that some of these people held to.” Though he also feels like the Book of Mormon provide an antidote: “But, I think that it’s just, they need to partake of the blessings of the Book of Mormon. Because if they don’t, then they see what happens. They see they are led away, led astray, and they don’t live by the things that they need to do.”

With the pride cycle reading by Catawba people, it becomes clear that the Book of Mormon is not just a narrative read onto Indigenous peoples by white Mormons. Some Catawba people read their own history and community through the Book of Mormon and through Book of Mormon inspired narrative models such as the pride cycle. The Book of Mormon is read onto Catawba history and Catawba history is read through the Book of Mormon. Not only, then, is the Book of Mormon taken to be a “history of the American Indians,” but the history of the Catawba people is read to be an ongoing narrative extension of the Book of Mormon. Political factions become, in effect, the Nephites and the Lamanites. Periods of conflict are the natural result of straying from the God of the Book of Mormon. Catawbas are, in some readings at least, quite literally, a people of the book.

Conclusion: Linking East and West

So I will tell you a little of the oral history that has been passed down. And again I don’t know about the truth of it, but it is what it is. It’s as accurate as I remember it. So, Granddad Patterson, the story goes that Granddad Patterson had a mule. And he was in the fields plowing, and this must have been in the 1870s. So he was plowing his fields and, um, he stopped his mule to rest and he went to sit under a tree. And as he was sitting there he saw two men approaching him, off in the distance. And he waited and waited, and he looked at him. And finally they got to him and they said, ‘We want to show you that we have a history of your people.’ And it was the Book of Mormon. And he said, he threw open his arms and he said, ‘Where have you been? We knew you were coming. We’ve been waiting for you.’ And so, he received the missionaries, and received the lessons, and he wasn’t the first Catawba to be baptized. I think it was either one of his sons-in-laws. Probably Alonzo Canty was the first one. But Granddad Patterson was the first elder in the church. So, when the missionaries were there, there was a lot of persecution from other religious sects. And Granddad Patterson hid the missionaries in his cabin multiple times, and fed them, and one time there was a mob that was coming for the missionaries, and he got the missionaries out and took them into the woods and told them where to hide, and that kind of thing. But the first LDS services were held in his cabin, there on the land. So, I don’t know if it was, uh, you know, if it was any kind of a premonition for Granddad Patterson to join the church and then to migrate to Utah to be—or to Southern Colorado—to be closer to the headquarters of the church—or not. But I know they didn’t have anything in South Carolina [at that time], so they—probably with religious freedom, and acceptance for being Lamanites, and then being part of the church probably helped them direct their migration movement to Colorado.

I begin this concluding section with this passage from an interview with David Garce, a Western Catawba descendent, because it encapsulates several themes I have heard from both Western Catawba descendants and citizens of the Catawba Nation: passed-memories of the persecuted first Mormon missionaries to visit the Catawba, or, rather, of Catawba ancestors hiding these missionaries from their persecutors. In this version their coming is not a surprise but something anticipated by Catawba leaders. In this Western Catawba version it is Granddad Patterson. In the Catawba Nation it is often Chief Blue who is remembered in a similar position, as escort and protector of the missionaries. The above passage also seeks to explain why the Western Catawbas left, but it begins with the coming of the missionaries. If, as I suggest above, we can think of this as a pivotal moment in Catawba collective memory—as Lamanites, as Mormons, as a church-tribe entanglement that not every Catawba person totally agrees with today, but every one of them feels the effect of—then this is something shared by both citizens and descendants alike, east and west. Both have passed down stories about the early missionaries who came and changed the way they think about who they are—brought them a book to teach them (or remind them, some would say) of who they are. It is a book many of them continue to read, believe in, and use to articulate what it means to be Catawba and to be Indigenous.

For some Western Catawba people, being a Catawba descendent and being a descendant of Book of Mormon peoples becomes entangled and inseparable. When I asked Thomas Croasman, a retired professor at Brigham Young University–Idaho and a Western Catawba descendant, what it means to be Catawba, he replied, “Oh, it just means that that’s our heritage, you know—the blood of father Lehi flowing in my veins, and I’m glad for that.” That answer is twofold. On the one hand, it is heritage. “Some people are glad that they’re Italian, or glad that they’re from England, or Ireland, or whatever, and that’s fine. They should be. And we’re just proud to be Catawba.” For Croasman, Catawba descent is a national heritage, much like that of migrants from other nations overseas (you might say he’s Catawba-American). It is also something he carries in his veins: “the blood of father Lehi.”

For some Western Catawba people, being a Catawba descendent and being a descendant of Book of Mormon peoples becomes entangled and inseparable. When I asked Thomas Croasman, a retired professor at Brigham Young University–Idaho and a Western Catawba descendant, what it means to be Catawba, he replied, “Oh, it just means that that’s our heritage, you know—the blood of father Lehi flowing in my veins, and I’m glad for that.” That answer is twofold. On the one hand, it is heritage. “Some people are glad that they’re Italian, or glad that they’re from England, or Ireland, or whatever, and that’s fine. They should be. And we’re just proud to be Catawba.” For Croasman, Catawba descent is a national heritage, much like that of migrants from other nations overseas (you might say he’s Catawba-American). It is also something he carries in his veins: “the blood of father Lehi.”

David Garce, a Western Catawba descendant of James Patterson, also sees Book of Mormon identity as a more expansive category to which Catawba people, east and west, do or can belong. When I asked him how Mormonism fits into the story of the Western Catawbas, he replied, It sure fits in with Book of Mormon promises. And certainly the Catawbas were Lamanites, or descendants of Lamanites, and, as we know, the Book of Mormon was written for the Lamanites, and… it’s a story of our people… Catawbas back in the Nation have done wonderful things as members of the church. And they’re doing Christian things. And it’s great. And I think, there’s not a conflict, but there’s a parallel track between what we’re doing out here and they’re doing back there. I think the religious part of it has something to do with our heritage, in that we can, we can almost claim blessings from the Book of Mormon, and our faithfulness to the gospel principles that are taught in the Book of Mormon. …but they seem to be not, not so much parallel with being Catawba, but rather being Lamanite. I don’t know if that makes any sense or not. …So you can be a Catawba, for sure, and have all kinds of squabbles and disagreements and everything, but you can also be a Latter-day Saint who is a Lamanite and claim those blessings, and the pride of knowing that you are a descendant of Father Lehi, and all of the prophets that have come down from him.

This idea of a parallel track—that is, the idea that Eastern and Western Catawbas have had a similar experience in their respective locations (South Carolina and southern Colorado)— is one I have heard from a number of Catawba people I have spoken to. And while the Western Catawba descendants, in diaspora, may face a very difficult task in trying to gain enrollment or recognition as a Western Band, Lamanite identity is something that, in the minds of many Catawbas, links all of them to a much larger Indigeneity. A spiritualized Indigeneity that is still, nonetheless, located in the blood: “the blood of Father Lehi.” If geography, nationalism, and politics divide them, Indigeneity and the “blood of Father Lehi” is still something that many of them, on both sides, believe they share. And while this is not a narrative that all Catawba people agree upon, for many it is a powerful and expansive shared Indigenous identity. For Thomas Croasman, to be Catawba is to have the blood of father Lehi in your veins. Similarly, Sarah Ayers, late Catawba elder and master potter remembered by many in the Catawba nation today, also felt the presence of father Lehi. Speaking of her pottery she said, “I know who I’m representing with my work. I was once blessed that Father Lehi would help me in all endeavors that stand for the tribe in honor of our heritage.”75 Clay from the Catawba River shaped by hands guided by Father Lehi. The people of the river are a people of the book. They shape and are shaped by both.

This idea of a parallel track—that is, the idea that Eastern and Western Catawbas have had a similar experience in their respective locations (South Carolina and southern Colorado)— is one I have heard from a number of Catawba people I have spoken to. And while the Western Catawba descendants, in diaspora, may face a very difficult task in trying to gain enrollment or recognition as a Western Band, Lamanite identity is something that, in the minds of many Catawbas, links all of them to a much larger Indigeneity. A spiritualized Indigeneity that is still, nonetheless, located in the blood: “the blood of Father Lehi.” If geography, nationalism, and politics divide them, Indigeneity and the “blood of Father Lehi” is still something that many of them, on both sides, believe they share. And while this is not a narrative that all Catawba people agree upon, for many it is a powerful and expansive shared Indigenous identity. For Thomas Croasman, to be Catawba is to have the blood of father Lehi in your veins. Similarly, Sarah Ayers, late Catawba elder and master potter remembered by many in the Catawba nation today, also felt the presence of father Lehi. Speaking of her pottery she said, “I know who I’m representing with my work. I was once blessed that Father Lehi would help me in all endeavors that stand for the tribe in honor of our heritage.”75 Clay from the Catawba River shaped by hands guided by Father Lehi. The people of the river are a people of the book. They shape and are shaped by both.

Of course, again, not all Catawba people see it that way. As one Catawba man who has left Mormonism—or has been trying to leave it—told me, quite adamantly: I am not a Lamanite and I am not from the tribe of Manasseh. But the fact that he had to declare this in an effort to break that link suggests just how strong the association is connecting Catawba people to the Book of Mormon. ” The Blood of Father Lehi: Indigenous Americans and the Book of Mormon by Stanley J. Thayne A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies Chapel Hill 201671 Lucile C. Tate, LeGrand Richards: Beloved Apostle (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1982), 169.

72 According to a table in Douglas Summer Brown, The Catawba Indians: The People of the River (Columbia: South Carolina University Press, 1966), 340-48, Blue served from 1931-38, 1941-43; and 1956-58.

73 The story relates an incident that occurred in the Catawba Nation when Chief Blue’s son was shot, ostensibly by accident, by two tribal members who were reportedly known to be his political opponents. Chief Blue felt an urge to revenge his son’s death but instead knelt in prayer and plead for the power to forgive them until he was able to. The story was included in Marion G. Romney, The Power of God unto Salvation, Brigham Young University Speeches of the Year, Provo, 3 Feb. 1960, pp. 6–7, and has been reproduced in a number of church publications and talks since then, often citing that source. Its inclusion, for example, in the church’s Family Home Evening Resource Book (1997), under the topic “Forgiving,” means that the story is likely recited as part of family home evening lessons in Mormon homes throughout the world.

74 Doctrine and Covenants 38:39. This verse is perhaps most associated with church president Ezra Taft Benson’s landmark address “Beware of Pride,” Ensign, May 1989.

75 From a newspaper article, probably Church News, included in Judy Canty Martin, My Father’s People: A Complete Genealogy of the Catawba Nation (self published, 1999), photocopy of article preceding p. 136.

The above is from “The Blood of Father Lehi: Indigenous Americans and the Book of Mormon” page 114 – 122 by Stanley J. Thayne. A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Religious Studies Chapel Hill 2016

https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/indexablecontent/uuid:c63d9de5-f590-40c2-afe8-510e0bb4653a

Life Details of Chief Samuel Blue

Chief Samuel Taylor Blue’s birthdate has never been pinned down. His birth was August 15, year between 1870/79. Possibly around 1872/73 due to birth dates of his children.

Samuel’s mother was Margaret George Brown, one of the last native speakers of Catawba. His father was a white man, named Samuel Blue. It was stated that his father was born in Fort Mill, SC. Per 1850 Census a Samuel Blue was living in York, SC, aged 25, with a wife Sarah Blue and two young children, Araminta Blue and John Blue. This 1850 Census states that Samuel T Blue was born in Lancaster, SC. His father is said to have died about 1878 leaving his wife and children to provide for themselves. Per 1900 and 1910 Census Margaret Brown is listed as a widow.

1880 Census listed Samuel T Blue as Samuel T Brown, after his mother. Chief Samuel T Blue’s first marriage was to Minnie Hester George. This marriage took place in July 1887 when Samuel was only fourteen years old. Minnie Hester George was born September 19, 1871 and died December 28, 1896 or in the spring of 1897.

Samuel remarried Louisa Hester Jean Canty on May 8, 1897 and it’s said the marriage was three months after the death of his first wife, putting that death date roughly in February 1897. Louisa Hester Jean Canty was the daughter of George and Betsy Canty. She died on July 9, 1963.

Samuel Taylor Blue became chief of the Catawbas’ as early as 1928 and served in that capacity at various times until his death, which occurred on April 16, 1959. On May 7, 1897, Blue had been baptized into The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in South Carolina. He also served as branch president of the Latter-day Saints Church on the Catawba Reservation until his death in 1959, serving a total of 40 years. In 1952 Samuel was a speaker at the dedication of the Catawba Branch Building, a dedication performed by David O. McKay.

Samuel Taylor Blue became chief of the Catawbas’ as early as 1928 and served in that capacity at various times until his death, which occurred on April 16, 1959. On May 7, 1897, Blue had been baptized into The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in South Carolina. He also served as branch president of the Latter-day Saints Church on the Catawba Reservation until his death in 1959, serving a total of 40 years. In 1952 Samuel was a speaker at the dedication of the Catawba Branch Building, a dedication performed by David O. McKay.

Samuel Taylor Blue allegedly had 23 children; three by his first wife and twenty by his second. Eleven of these children are said to have been stillborn, of whom five “died unnamed”. There are twelve known children of Chief Blue, three by his first wife and nine by his second. Only ten children survived to adulthood.

Children of Samuel Taylor Blue and Minnie Hester George:

1. Fred Nelson Blue b.10-25-1889 d.08-08-1980 he married Leola Watts.

2. Rodie Blue (daughter) died in infancy

3. Nora Lily (Lillie) Blue b 11-19-1893 d.05-1915 in childbirth, husband and father of child unknown.

Children of Samuel Taylor Blue and Louisa Hester Jean Canty:

1. Herbert Blue b.04-25-1898 d.04-1979, married Lavinia Harris 03-17-1915, daughter of D.A. Harris and Lizzie Patterson, she died 07-25-1916. He remarried Lula Addie Mae Blankenship.

2. Samuel Andrew Blue b.10-06-1900 d.09-18-1960, married Doris Belle Wheelock b.01-15-1905 d.05-14-1986, daughter of Archie and Rosa(Harris) Wheelock.

3. Joseph Harvey Blue b.03-14-1903 d.01-08-1914 of a gunshot wound.

4. Lula Samuel Henrietta Blue Beck b.05-03-1905 d. unknown, married Major John Beck.

5. Henry Leroy Blue b.08-14-1907 d. 07-11-2002, married Eva Mae Bodiford 01-21-1933, she was born in Alabama 10-19-1905 and died 04-21-1993.

6. Vera Louise Blue Sanders b. 08-21-1909 d. 03-16-1991, married Albert Henderson Sanders, son of William and Nora Sanders.

7. Guy Larson Blue b.12-03-1911 d. 02-07-1984, married Eva Bell George d.09-1982, they had several children including Chief Gilbert Blue.

8. Elsie Inez Blue George b.03-03-1914 d. unknown, married Landrum Leslie George on 09-03-1932, they had no children.

9. Arnold “Donny” Lee Blue b.11-23-1917 d. unknown, married Lillian Harris and had one son, Arnold Jr. who seemed to have died before the 1961 tribal roll.

Information obtained from Wikipedia, Thomas J Blummer, Catawba Indian Nation: Treasures in History (The History Press, 2007), page 101. Catawba Indian Genealogy – Ian Watson, pages 16-19

More information on Chief Blue and the Catawba Nation below.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gilbert_Blue

http://www.indianz.com/News/2008/007186.asp

http://www.indianz.com/News/2007/004024.asp

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Catawba_people

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catawba_people#/media/File:Indians_NW_of_South_Carolina.jpg

https://archive.org/details/cumorahsouthern2906eng

History

A c. 1724 English copy of a deerskin Catawba map of the tribes between Charleston (right) and Virginia (right) following the displacements of a century of disease and enslavement and the 1715–7 Yamasee War. The Catawba themselves are labelled as “Nasaw”.

A c. 1724 English copy of a deerskin Catawba map of the tribes between Charleston (right) and Virginia (right) following the displacements of a century of disease and enslavement and the 1715–7 Yamasee War. The Catawba themselves are labelled as “Nasaw”.

From the earliest period, the Catawba have also been known as Esaw, or Issa (Catawba iswä, “river”), from their residence on the principal stream of the region. They called both the present-day Catawba and Wateree rivers Iswa. The Iroquois frequently included them under the general term Totiri, or Toderichroone, also known as Tutelo. The Iroquois collectively used this term to apply to all the southern Siouan-speaking tribes.

Albert Gallatin (1836) classified the Catawba as a separate, distinct group among Siouan tribes. When the linguist Albert Samuel Gatschet visited them in 1881 and obtained a large vocabulary showing numerous correspondences with Siouan, linguists classified them with the Siouan-speaking peoples. Further investigations by Horatio Hale, Gatschet, James Mooney, and James Owen Dorsey proved that several tribes of the same region were also of Siouan stock.

In the late nineteenth century, the ethnographer Henry Rowe Schoolcraft recorded the purported Catawba traditions about their history, including that they had lived in Canada until driven out by the Iroquois (supposedly with French help). They migrated to Kentucky and to Botetourt County, Virginia. By 1660 they had migrated south to the Catawba River, contesting it with the Cherokee in the area. The Kentucky River was also known as the Catawba River at times. Catawba Tribe was later a subtribe under Cherokee Chiefs authority at times. Limhi under Lamanites similarity??

But, 20th-century anthropologist James Mooney later dismissed most elements of Schoolcraft’s record as “absurd, the invention and surmise of the would-be historian who records the tradition.” He pointed out that, aside from the French never having been known to help the Iroquois, the Catawba had been recorded by 1567 in the same area of the Catawba River as their later territory. Mooney accepted the tradition that the Catawba and Cherokee had made the Broad River their mutual boundary, following a protracted struggle.

The Catawba were long in a state of warfare with northern tribes, particularly the Iroquois Seneca, and the Algonquian-speaking Lenape, a people who had occupied coastal areas and had become vassals of the Iroquois after migrating out of traditional areas due to European encroachment. The Catawba chased their raiding parties back to the north in the 1720s and 1730s, going across the Potomac River. At one point, a party of Catawba is said to have followed a party of Lenape who attacked them, and to have overtaken them near Leesburg, Virginia. There they fought a pitched battle.

Similar encounters in this longstanding warfare were reported to have occurred at present-day Franklin, West Virginia(1725), Hanging Rocks and the mouth of the Potomac South Branch in West Virginia, and near the mouths of Antietam Creek (1736) and Conococheague Creek in Maryland. Mooney asserted that the name of Catawba Creek in Botetourt came from an encounter in these wars with the northern tribes, not from the Catawba having lived there.

Similar encounters in this longstanding warfare were reported to have occurred at present-day Franklin, West Virginia(1725), Hanging Rocks and the mouth of the Potomac South Branch in West Virginia, and near the mouths of Antietam Creek (1736) and Conococheague Creek in Maryland. Mooney asserted that the name of Catawba Creek in Botetourt came from an encounter in these wars with the northern tribes, not from the Catawba having lived there.

The colonial governments of Virginia and New York held a council at Albany, New York in 1721, attended by delegates from the Six Nations (Haudenosaunee) and the Catawba. The colonists asked for peace between the Confederacy and the Catawba, however the Six Nations reserved the land west of the Blue Ridge mountains for themselves, including the Indian Road or Great Warriors’ Path (later called the Great Wagon Road) through the Pennsylvania, Virginia, North Carolina and Georgia backcountry. This heavily traveled path, used until 1744 by Seneca war parties, went through the Shenandoah Valley to the South.

In 1738, a smallpox epidemic broke out in South Carolina. It caused many deaths, not only among the Anglo-Americans, but especially among the Catawba and other tribes, such as the Sissipahaw. They had no natural immunity to the disease, which had been endemic in Europe for centuries. In 1759, a smallpox epidemic killed nearly half the tribe. Native Americans suffered high fatalities from such infectious Eurasian diseases.

In 1744 the Treaty of Lancaster, made at Lancaster, Pennsylvania, renewed the Covenant Chain between the Iroquois and the colonists. The governments had not been able to prevent settlers going into Iroquois territory, but the governor of Virginia offered the tribe payment for their land claim. The peace was probably final for the Iroquois, who had established the Ohio Valley as their preferred hunting ground by right of conquest. The more western tribes continued warfare against the Catawba, who were so reduced that they could raise little resistance. In 1762, a small party of Algonquian Shawnee killed the noted Catawba chief, King Hagler, near his own village. From this time, the Catawba ceased to be of importance except in conjunction with the colonists.

In 1763, South Carolina confirmed a reservation for the Catawba of 225 square miles (580 km2; 144,000 acres), on both sides of the Catawba River, within the present York and Lancaster counties. When British troops approached during the American Revolutionary War in 1780, the Catawba withdrew temporarily into Virginia. They returned after the Battle of Guilford Court House, and settled in two villages on the reservation. These were known as Newton, the principal village, and Turkey Head, on opposite sides of Catawba River. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catawba_people

19th-century

“In 1826, the Catawba leased nearly half their reservation to whites for a few thousand dollars of annuity, on which the few survivors (as few as 110 by one estimate[8]) chiefly depended. In 1840 by the Treaty of Nation Ford with South Carolina, the Catawba sold all but one square mile (2.6 km2) of their 144,000 acres (225 sq mi; 580 km2) reserved by the King of England to the state. They resided on the remaining square mile after the treaty. The treaty was invalid ab initio because the state did not have the right to make it and did not get federal approval.[9] About the same time, a number of the Catawba, dissatisfied with their condition among the whites, removed to join the eastern Cherokee in western North Carolina. But, finding their position among their old enemies equally unpleasant, all but one or two soon returned to South Carolina. An old woman, the last survivor of this emigration, died among the Cherokee in 1889. A few Cherokee intermarried with the Catawba.

At a later period some Catawba removed to the Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory and settled near present-day Scullyville, Oklahoma. They merged with the Choctaw and did not retain separate tribal identity.

Starting in 1883–84, a large number of Catawba joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and some migrated west with them to Colorado.

Religion and culture

The Catawba women were well known for their pottery in the Carolinas.

The Catawba women were well known for their pottery in the Carolinas.

The customs and beliefs of the early Catawba were documented by the anthropologist Frank Speck in the twentieth century.

In the Carolinas, the Catawba became well known for their pottery, which was made by the women.[10]

In approximately 1883, tribal members were contacted by Mormon missionaries. Numerous Catawba were converted to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and some migrated to Colorado and Utah and neighboring western states.[11]

The Catawba hold a yearly celebration called Yap Ye Iswa, which roughly translates to Day of the People, or Day of the River People. Held at the Catawba Cultural Center, proceeds are used to fund the activities of the center.

20th century to present

The Catawba were electing their chief prior to the start of the 20th century. In 1909 the Catawba sent a petition to the United States government seeking to be given United States citizenship.[12]

During the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration, the federal government worked to improve conditions for Native Americans. Under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, tribes were encouraged to renew their governments for more self-determination. The Catawba were not at that time a recognized Native American tribe. In 1929 the Chief of the Catawba, Samuel Taylor Blue, had begun the process to gain federal recognition. The Catawba were recognized as a Native American tribe in 1941 and they created a written constitution in 1944. Also in 1944 South Carolina granted the Catawba and other Native American residents of the state citizenship, but not to the extent of granting them the right to vote. Like African Americans, they were largely excluded from the franchise. That right would be denied the Catawba until the 1960s, when they gained it as a result of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which provided for federal enforcement of people’s constitutional right to vote..

As a result of the federal government’s Indian termination policy in the 1950s of its special relationship with some Indian tribes that it determined were ready for assimilation, it terminated the government of the Catawba in 1959. This meant also that the members of the tribe ceased to have federal benefits, their assets were divided, and the people were subject to state law. The Catawba found that they preferred to be organized as a tribal community. Beginning in 1973, they applied to have their government federally recognized, with Gilbert Blue serving as their chief until 2007. They adopted a constitution in 1975 that was modeled on their 1944 version.

In addition, for decades the Catawba pursued various land claims against the government for the losses due to the illegal treaty made by South Carolina in 1840 and the failure of the federal government to protect their interests. In 1993 the federal government reversed the “termination”, recognized the Catawba Indian Nation and, together with the state of South Carolina, settled the land claims for $50 million to go toward economic development for the Nation.[13]

With the late 20th-century governmental recognition of the right of Native Americans to conduct gambling on sovereign land, the Catawba set up such enterprises to generate revenue. In 1996, the Catawba formed a joint venture partnership with D.T. Collier of SPM Resorts, Inc. of Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, to manage their bingo and casino operations. That partnership, New River Management and Development Company, LLC (of which the Catawba were the majority owner) operated the Catawba’s bingo parlor in Rock Hill, for several years.

When in 2004 the Catawba entered into an exclusive management contract with SPM Resorts, Inc., to manage all new bingo facilities, some tribal members were critical. The new contract was signed by the former governing body immediately prior to new elections. In addition, the contract was never brought before the General Council (the full tribal membership) as required by their existing constitution.[14] After the state established the South Carolina Education Lottery in 2002, the tribe lost gambling revenue and decided to shut down the Rock Hill bingo operation. They sold the facility in 2007.[15]

In 2006, the Catawba filed suit against the state of South Carolina for the right to operate video poker and similar “electronic play” devices on their reservation. They prevailed in the lower courts, but the state appealed the ruling to the South Carolina Supreme Court. The state Supreme Court overturned the lower court ruling. The tribe appealed that ruling to the United States Supreme Court, but in 2007 the court declined to hear the appeal.[16]

On July 21, 2007, the Catawba held their first elections in more than 30 years. Of the five members of the former government, only two were reelected.[17]

In the 2010 census, 3,370 people claimed Catawba ancestry. 2,025 of them were full-blooded.” Wikepedia/Catawba

A Study of the Influence of the Mormon Church on the Catawba Indians of South Carolina

1882-1975 Jerry D. Lee Brigham Young University – Provo

https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5870&context=etd