Hebrew Blood

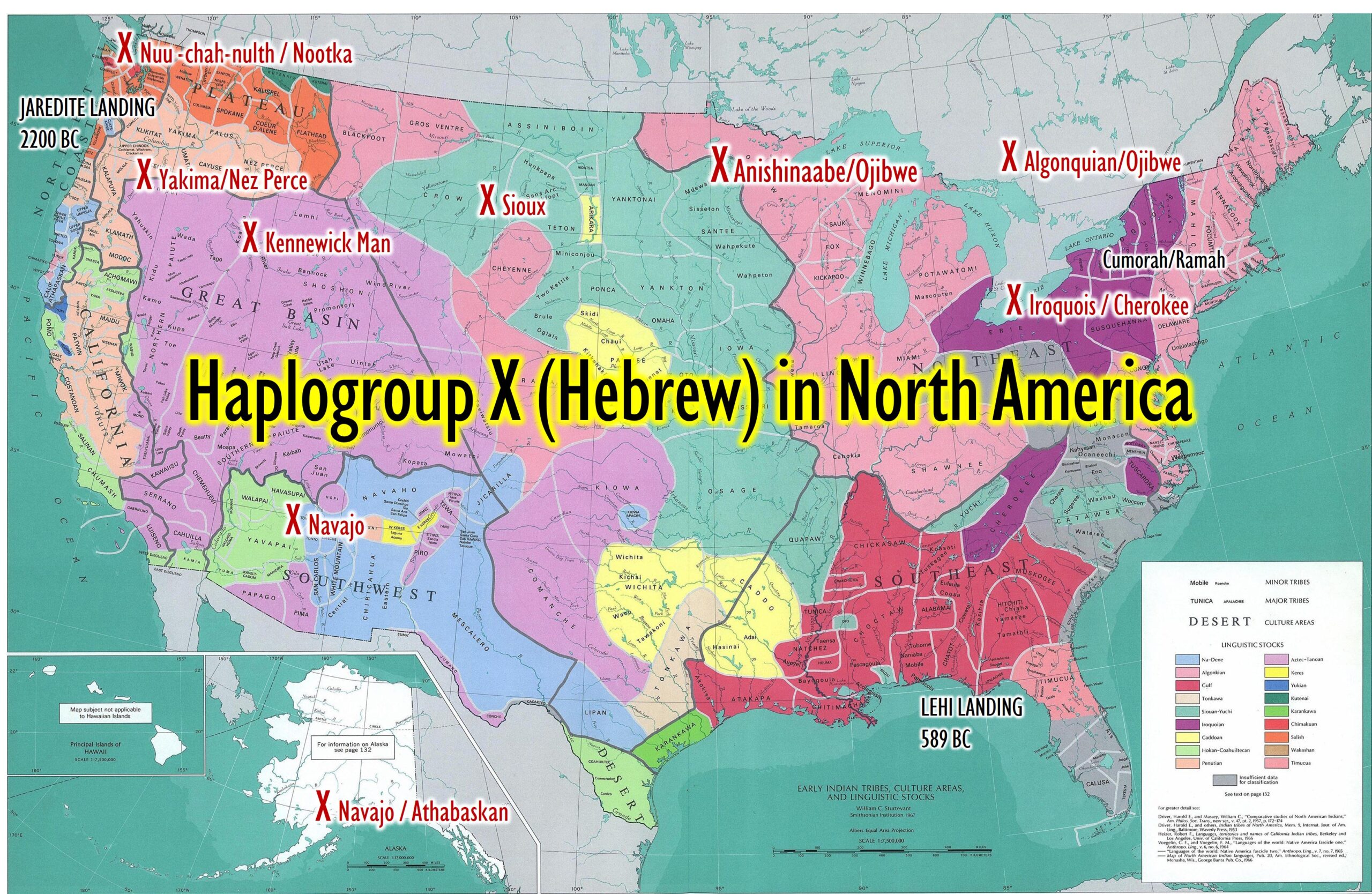

Hopi, Navajo, Aztec and Mayan all have Asian DNA. Only the North American Tribes near the Great Lakes have Hebrew blood. See National Geographic link here.

The Mayans and Aztecs are not Hebrew as the BofM says the Lamanites are in the scriptures that follow. Experts and Historians have shown that the people all along the west coast of the United States from Alaska to California have Asian markers. The same is true of the Mesoamerican and Central and South American Natives.

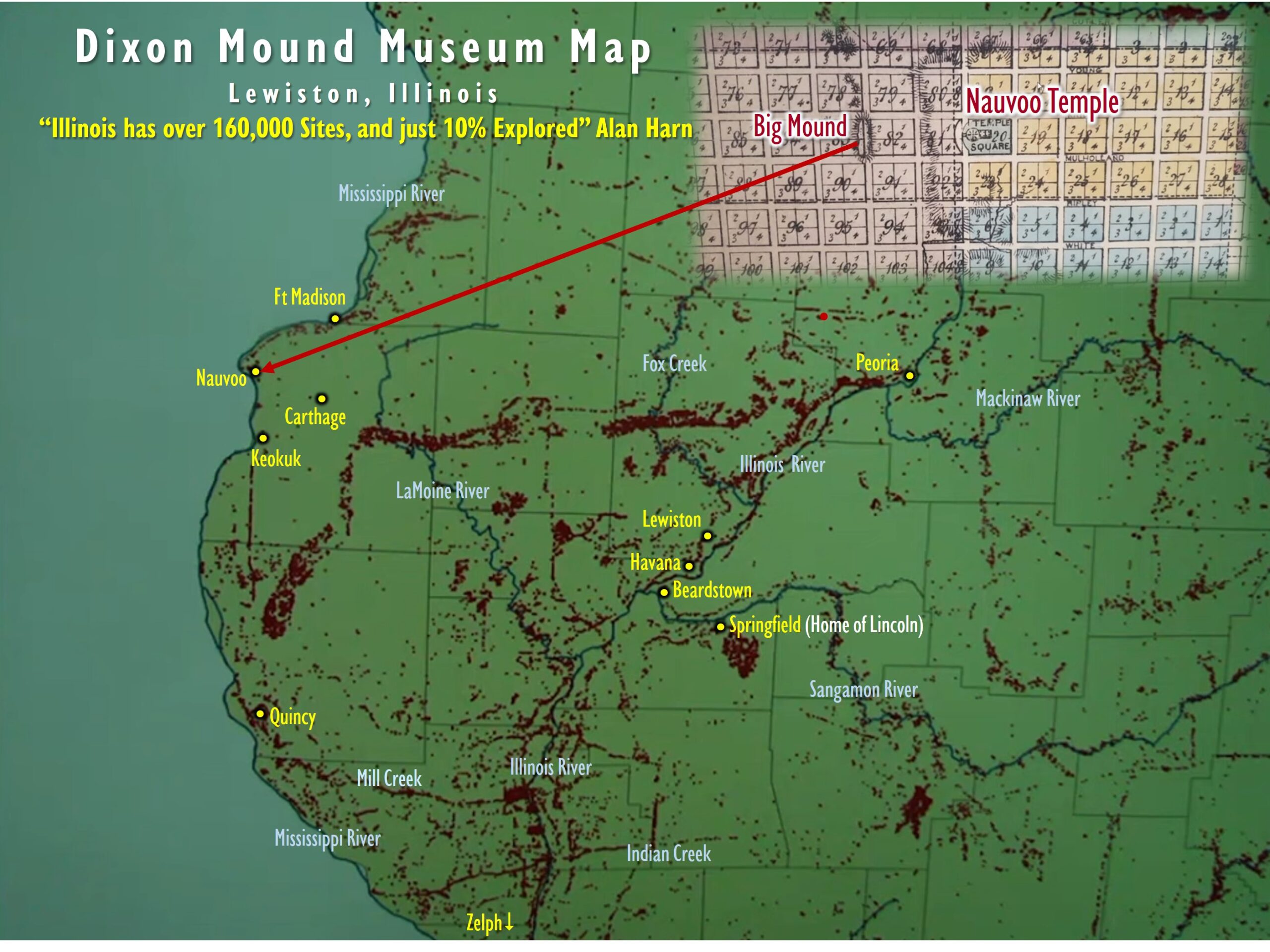

Research into DNA studies continues to show new evidence that many Native Americans east of the Mississippi have the same Haplogroup X as many in western Eurasia. As the experts continue to try and explain away this evidence, the more I become excited about it. Those in the scientific arena continually want to push the narrative of their great theories about Evolution, Climate Change, Old Earth, Noah’s Flood Myth, etc. With the new information from our recent Book, The Annotated Edition of the Book of Mormon, I am excited to continue the path of learning. I am finding some amazing things about DNA and a connection between the Lamanites and the Hebrew. It just makes sense that they are related as we know the Mulekites were Hebrew and they surely left evidence of the Native Americans in North America didn’t they? We have also found many evidences of the Hebrew language and Hebrew artifacts in North America. See my blog with additional articles here, here, and here.

The Hebrews and the Natives east of the Mississippi have similar DNA and were smitten and scattered, and driven during the “Trail of Tears.” No such scattering by the Gentiles towards the South American Natives has occurred.

“A great nation (the United States of America) shall be set up… by the power of God, so that the gospel may be restored, the Book of Mormon come forth, its message go to the American remnant of Jews, that the eternal covenants of the Lord with his people might be fulfilled.” “The remnant of Jacob, including the Lamanites in the Americas”, will assist in the gathering of Israel to the promised land New Jerusalem.” McConkie, Bruce R., Mortal Messiah, Book 4, 1981, pp. 348-349, 358

CALLING ALL CHEROKEES

1956.0567 A B. Audience Given by the Trustees of Georgia to a Delegation of Creek Indians, by William Verelst, London, 1734-35, Oil on canvas, 1956.0567 A, B. Gift of Henry Francis du Pont, Courtesy of Winterthur Museum. Photo by James Schneck, Staff Photographer. © 2013 Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library.

Detail of cartouche with key. © 2013 Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library.

Were they really that red? The scientist Constantine Rafinesque said in 1840 there was never a red Indian in the Americas unless so painted, and French naturalists recorded in 1653 that “they are all born perfectly white, but they change the natural color of their skin by the frequent use of a certain ointment that they create with bear grease and the root of an herb that has the virtue of inuring them against heat and cold.” (Translated from the French in App. D, “Digression Containing a Summary of the History of the Land of the Apalachites,” Cherokee DNA Studies II: More Real People Who Proved the Geneticists Wrong [forthcoming], p. 388-89 in the French edition of 1681 published in Rotterdam.) https://dnaconsultants.com/calling-all-cherokees/

Were they really that red? The scientist Constantine Rafinesque said in 1840 there was never a red Indian in the Americas unless so painted, and French naturalists recorded in 1653 that “they are all born perfectly white, but they change the natural color of their skin by the frequent use of a certain ointment that they create with bear grease and the root of an herb that has the virtue of inuring them against heat and cold.” (Translated from the French in App. D, “Digression Containing a Summary of the History of the Land of the Apalachites,” Cherokee DNA Studies II: More Real People Who Proved the Geneticists Wrong [forthcoming], p. 388-89 in the French edition of 1681 published in Rotterdam.) https://dnaconsultants.com/calling-all-cherokees/CHAPTER 7: IN THE KINGDOM OF THE APALACHE

The 1600s brought an almost unbelievable degree of admixture and population change to the Southern Highlands. In fact, little of what demonstrably occurred has been believed. Hang onto your colonial cap because it’s going to be a bumpy ride!

Fig. 1: FACT OR FANTASY: The Apalache capital Melilot identified by Richard Thornton as the Nacoochee Valley in North Georgia depicted by Edouard Graeves in 1653.

A link between the English colonists who disappeared in 1590 and the new demography of the following century is Virginia Dare. Did the first white child born in Virginia perish sometime between her birth on August 18, 1587, followed a few weeks later by her grandfather John White’s sailing for England, and his landing on a deserted Roanoke Island on August 16, 1590 on his return, or did she live on as one of the survivors of the “lost” colony? Most historians favor the first alternative. Some imagine she died as a baby with a tomahawk embedded in her skull. In the Episcopal Diocese of East Carolina she and Manteo have been elevated to the status of martyrs.

Icon created by Cheryl Hendrick for the feast day of Manteo and Virginia Dare (August 18). All Saints Episcopal Church, Kitty Hawk, North Carolina.

There is a tiny minority of historians who believe the Lost Colony was never lost to begin with. A quartz tablet was discovered by L. E. Hammond in Chowan County, North Carolina in September 1937, engraved with a record signed by Eleanor Dare, Virginia’s mother, the daughter of John White. It described the slaughter of the entire colony save seven:

The Dare Stones

“The famous – and, to some, infamous – Dare Stones have been a part of Brenau University lore since the late 1930s. It is a collection of a large number of engraved rocks that emerged at the height of the Great Depression purporting to solve the mystery of The Lost Colony of Roanoke, a group of settlers on an island off the coast of North Carolina that disappeared without a trace in the late 16th century. Although most of the stones are generally regarded as artifacts of artifice, the first remains of great interest to historians and archaeologists. It appears to be a message from one of the colonists, Eleanor White Dare, to her father, John White, the colony’s governor, who returned to America from a three-year trip to England to find his daughter, son-in-law and granddaughter missing along with all the others he had left at Roanoke.” Brenau University

FRONT of the Stone

Ananias Dare & Virginia went hence Vnto Heaven 1591 Anye Englishman Shew John White Govr Via

BACK of the Stone

Father soone After yov goe for Englande wee cam hither/ Onlie misarie & Warre tow yeere/ Above half DeaDe ere tow yeere more from sickeness beine fovre & twentie/ salvage with message of ship vnto vs/ small space of time they affrite of revenge ran al awaye/ wee bleeve yt nott you/ soone after ye salvages faine spirts angrie/ suddiane murther all save seaven/ mine childe—ananias to slaine wth mvch misarie–/ bvrie al neere foure myles east this river vppon small hil/ names writ al ther on rocke/ pvtt this ther alsoe/ salvage shew this vnto yov & hither wee promise yov to give greate plenty presents E W D[1]

In other words, Eleanore Dare wanted anyone who found the inscription to let her father, the governor of the colony, know that soon after he went back to England in 1587 the colonists removed themselves from Roanoke. After two years of nothing but war and misery, and after two more years of sickness, with a false report having been received of White’s ship sighted, half the colonists were dead. They were then fallen upon by the Indians in a rage and murdered, all but seven. These the survivors buried upon a small hill four miles east with memorial stones. “My child and Ananias, too, slain with much misery.”

That seven colonists survived seemed to be echoed by Secretary William Strachey’s intelligence at Jamestown in 1610:

…at Ritanoe, the Wewroance (king) Eyanoco preserved 7 of the English alive—fower men, twoo boyes, and one young Maid, who escaped and fled up the River of Choanoke—to beat his copper.”[2]

The Choanoke find was followed by other inscriptions coming to light over the next couple years. These are all currently preserved in a collection at Brenau College in Gainesville, Georgia, a few miles north of Atlanta.

Wait, weren’t the Dare Stones proven to be forgeries?

As the author of a detailed monograph on the mysterious stones points out, it must have been a diabolically clever forger to mix truth and lies in such a fashion, in Elizabethan English. Why so many iterations of the same fantastic tale, scattered across several states? “The simplest forgery is the best.” No gloating hoaxer ever came forward, and no forgers were ever exposed. The story is much like that of the ninth-century Latin and Hebrew texts on the Tucson Artifacts excavated in the 1920s, branded by academic authorities as “manufactured history.”[3] Both finds turn American history as it is complacently conceived on its ear.

In 1939, there were twenty-four stones in the museum of Brenau College. College officials convened a number of scientists and historians on October 21-22 for the purpose of discussing them. Presiding was Samuel Eliot Morrison, the professor at Harvard who had just written the maritime history of New England and who was soon to publish a series of classic books on Columbus, Portuguese voyages of discovery and related subjects in early American history. No more august and fitting figure could be imagined. At the close of the conference, Morrison was placed in charge of appointing a committee of five with himself as chairman to publish conclusions, “if any,” and a verdict on the stones.

In the meantime, what was evidently a “hit job” appeared in a popular New York magazine. It was titled “Writ on Rocke: Has America’s First Murder Mystery Been Solved?” and was by-lined by the “reporter,” Boyden Sparkes. It made mince-meat of the whole affair in a long critical essay that seemed to leave no stone … well, unturned. Sparkes attacked the discoverers as bumptious amateurs and money-hungry adventurers. He questioned the style, sense and age of the inscriptions and concluded that the small Baptist girl’s college used the collection as a pretext for “publicizing the school” and angling to get a Hollywood movie offer. Some commentators suggested he had been explicitly commissioned to put an end before it even got started to a rival historical pageant in North Carolina. If that was its true purpose, Sparkes’ foray into American colonial history certainly had its effect. Paul Green’s outdoor costume musical “The Lost Colony,” premiered on Roanoke Island on July 4, 1937 with biblical amounts of hoopla and state and federal funding and went on to become one of the longest-running, biggest grossing spectacles in the world. As of summer 2019, more than four million visitors had seen it—probably more by now. It was not the first time North Carolina was to win out over Georgia in manipulating history. Green’s production inspired “Unto These Hills,” the outdoor drama that introduced a Hollywood version of Cherokee history to millions of people beginning in 1950.

But what about Professor Morrison’s blue-ribbon committee? Oddly, even Sparkes acknowledged things were looking bad for North Carolina and good for Georgia:

Last fall thirty-four scholars, headed by Dr. Samuel E. Morison [sic], of Harvard, president of the American Antiquarian Society, journeyed to Brenau and after two days’ study pronounced that “the preponderance of evidence points to the authenticity of the stones.”[4]

Notice that it is practically de rigueur for famous journalists to misspell the names of their most important sources, just as it has been customary since the earliest days to describe a trip from Boston or New York to the backwoods of Georgia as a “journey.”

Morrison, the acclaimed specialist and popular writer on the discovery of America, like the champion of the Tucson Artifacts at the University of Arizona, Byron Cummings, known as the Father of Southwest Archeology, never backed away from his verdict that the Dare Stones were authentic and of national importance. He believed they completely rewrote colonial history. Readers today can choose between taking the opinion of an academic and popular hero, a Rear Admiral who retraced Columbus’ voyages with his own ship and won two Pulitzer Prizes, or a forgotten hack from Madison Avenue.

The Dare Stones are genuine and very informative. They provide evidence that sixty-four of the Roanoke colonists died or were murdered by the Indians. After the massacre of seventeen colonists including Virginia and her father Ananias Dare in 1591, the remaining seven, guided by “four goodli men,” headed southwest. “Goodly” indicates they were civilized, if not Christians.

Thirteen stones found by William Eberhart in Greenville County, South Carolina in the 1930s (nos. 2-14) continue the chronicles. One is the memorial of “Dyonis Harvie wife & Dowter, Wil Dye, spend love, 1591, Myrthered bye salvage.” The last traces of the party are recorded on stones 15-47, found in Hall County and Fulton County, Georgia, in Apalache Country. Before Eleanor Dare died in 1599 (no. 25), we learn that the seven survived “here” from 1593, “here” being “a great salvage lodgement,” whose king took Eleanor “tow wyfe” (no. 26). In 1598, word is that “we have sent many savages to look for you” (no. 27). In 1598, Eleanor beseeches her John White to have her daughter with the savage king “goe to englande” (no. 28). In 1599, she sickens and dies. In the years down to 1603, someone else carves the memorials. The stones record the deaths of William Wythers, Robert Ellis, Henry Berry, Thomas Ellis, Griffin Jones, James Lassie and Agnes Dare, the half-blood daughter of the Indian king and Eleanor.[5]

Giving a daughter the name of Agnes provides a strong clue to the ethnicity of the Dares. There is a christening record of an Agnis Dare, possibly a relative of Ananias Dare, Eleanor’s husband, in Lyme Regis, Dorset, October 15, 1554. Her father was Thomas Dare (about 1530-1580), merchant and goldsmith. Thomas Dare came from an ancient West Country family that has been documented in records back to 1265.[6] The surname also appears as Deere, Dere and Deor, after the animal or a form of “beloved.” Ananias Dare was cut from the same cloth as the earliest English explorers and privateers, the Drakes, Raleighs, Hawkins, Gilberts and Grenvilles. It would make sense for him to marry Eleanor White, the daughter of an artist, lay minister and politician.

Like many of the Welsh, including the Tudor Queen Elizabeth herself, these Dares were probably of Jewish or crypto-Jewish descent.[7] In this period, however, and probably ever since the era when English Jews were proscribed in the thirteenth century, they identified as staunch Protestants. According to the author of a Dare timeline, the years between 1500 and 1700 were their heyday. It was a time when Lyme Regis with “its merchants and sea captains trading with the Mediterranean, West Indies and Americas,” was a major English seaport, even more consequential than Bristol or Liverpool. John William Dare, who left a will in 1542, was a merchant of Madras, India. In 1563, Thomas Dare was elected mayor of Lyme Regis. And in 1588 the decisive battle with the invading Spanish Armada took place within sight of Lyme Regis.

What motives might a forger have had to fake the Dare Stones and plant them in scattered locations across three different states? We cannot imagine. But we can imagine why the Eleanor Dare inscriptions might have disturbed opinion leaders in 1938. It was a time when a narrow WASP elite tightly controlled academia, education, government and the media. It would have been easy to squelch a national origin story that included the following elements:

- A strong woman who heroically led the remnants of a failed European colony through the perils of the North American wilderness and inadvertently recorded their names and exploits for posterity

- Indians who were quite civilized, and Christian to boot

- A system of trade paths and, in effect, mail, or at least communications, that reached across tribal territories from the Carolina coast to the Blue Ridge Mountains

- A king among the Indians who lived in a glittering metropolis in what is now North Georgia and took an Englishwoman for his wife, producing the first half white, half Indian child born in the territories that became the United States

What if word of this early start to North American history had gotten out at the time? If Indians, or at least some of them, were civilized, it could completely undermine the rationale for destroying or removing them. Indians were fully human and were not to be despised or injured. If they had already been converted to Christianity, they were not heathens occupying an undiscovered land. Their domains had already been reached by a “Christian prince.” And if they had kings, the aristocracy of Europe would have to recognize them, a dilemma that soon faced James I with Pocahontas. Finally, the thought that an Indian male could happily “take to wife” an Englishwoman in holy matrimony and have legitimate issue undoubtedly caused people no end of anguish. It was supposed to go the other way.

Little Ado About Much

Where did Eleanor Dare and her companions end up exactly? She fled to the kingdom of the Apalache in North Georgia.

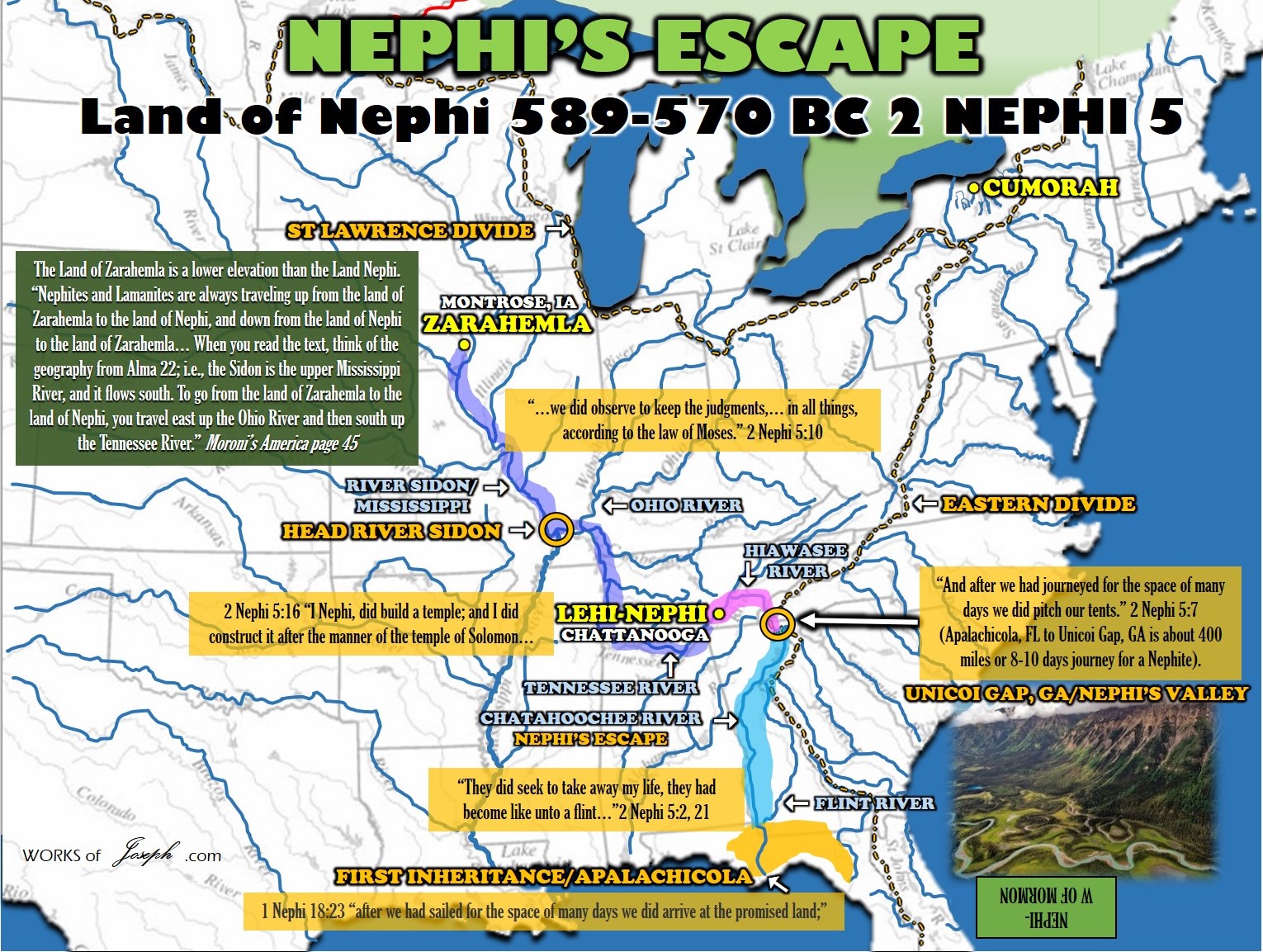

(Editors note: This is near Unicoi Gap where I feel may be where Nephi arrived to get away from Laman and Lemuel up the Chattahoochee River from the Tallahassee, FL area where Lehi probably landed. See map below.)

What we know about the Apalaches in the early colonial period of American history is almost entirely derived from a single source. This is an early Huguenot emigration guide titled Histoire Naturelle et Morale des Les Antilles de l’Amerique by Charles de Rochefort (1605-1683). The work was published in 1658 in Rotterdam, a hotbed of French, Dutch and Walloon Protestant intellectual activity at the time. It was translated into English as The History of the Caribby-Islands, by John Davies, in 1666. After several other editions, a second, augmented edition was issued in 1681.” https://dnaconsultants.com/chapter-7-in-the-kingdom-of-the-apalache/

“The Lost Colony”

“The settlement now known as “The Lost Colony” was England’s second attempt to colonize the Virginia territory in North America, following the failure of Ralph Lane’s 1585 Roanoke settlement: 45, 80–81 The colonists arrived at Roanoke in July 1587, with John White as the appointed governor.[3]: 82, 89 Their intended destination was Chesapeake Bay, but the crew of the expedition refused to take them farther than Roanoke.[3]: 81–82, 89 Hostilities between Lane’s colony and the mainland Secotan tribe made Roanoke a dangerous choice for a new colony, although White’s group was able to renew friendly relations with the Croatan on nearby Croatoan Island: 90–92…

The story of the Lost Colony became popular in the United States following several dramatic accounts published in the 1830s: 124–130 Eleanor Dare’s daughter, Virginia Dare, who was the first child born in an English colony in the New World, became an iconic figure, and celebrations of her birthday became a major North Carolina tourist attraction: 276–277, 294 In 1937, a Paul Green play, The Lost Colony, debuted on Roanoke Island. President Franklin D. Roosevelt attended a performance on Virginia Dare’s 350th birthday…

The Chowan River Dare Stone. On November 8, 1937, Louis E. Hammond visited Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, with a 21-pound (9.5 kg) stone, asking for help to interpret the markings on it: 9–10 Hammond claimed to be a California tourist traveling the country with his wife. He said he found the stone in August 1937 by the east bank of the Chowan River, in Chowan County, North Carolina: 7–9.” Wikipedia