The Forefathers of the American Indians came from Jerusalem

“I rejoice in the work that is being accomplished both at home and abroad. I rejoice in the manifestations of the Spirit of God, that come to each and every one of our elders who faithfully perform the duties devolving upon them. I rejoice in the fact that God opens the way and prepares the hearts of the honest in every land and clime, wherever this Gospel of Jesus Christ has gone. It is also a source of joy and satisfaction to me that, in all my journeys at home and abroad, wherever I go, wherever I mingle with people, I am constantly receiving additional evidence and testimony regarding the divinity of this work in which we are engaged, As I journeyed away from home, and as I mingled with people, I would feel sorrowful if I had constantly been finding objections to the plan of life and salvation, that required exertion on my part to explain away. It would be a source of regret if I were constantly finding obstacles in the path, regarding the divinity of the work of God, which we have espoused. But, I have never found any such obstacles: I have never found anything that needed to be explained away: everything points to the divinity of the work.

“While listening to the remarks of Brother Ivins, referring to a book that was written by one of our enemies, in which the statement is made that there is not a particle of evidence to show that there is any trace of the Hebrew among the people who anciently inhabited this country, and that there is no evidence that would go to prove that the Book of Mormon is true. I was reminded of a little item of evidence that came under my observation while I was in the City of London. A gentleman there, to whom a very dear friend of mine, Col. Alex. G. Hawes, had given me a letter, kindly invited a number of newspaper men to his home to meet me. I am very sorry that the newspaper men declined the honor; but I had the privilege of meeting with this man and his family, and a few friends, and conversing with them. One of his friends had been a member of the British legation at Constantinople and had spent a considerable portion of his life there. He had traveled all over the holy land and was familiar with the people and their customs. Among other things, he said: “Mr. Grant, I was astonished beyond measure, when I visited Canada, to find there oriental patterns woven in beads, by the American Indians. They were the same patterns that were woven in rugs, in the oriental countries. I have traveled extensively, and I had never seen those oriental patterns in any part of the world except in the holy land, until I found them among the North American Indians. Those patterns have been handed down for hundreds of years, from generation to generation ; they are kept in families, and can be found nowhere else; and how under the heavens those Indians, who have no connection with the people of the holy land, should have the same patterns is a mystery to me.” “Well, mv friend,” I said, “if I were to inform you that the forefathers of these American Indians came from the city of Jerusalem, that would explain it, wouldn’t it?” He replied, “Well, of course, it would.” I asked him if he had ever read the Book of Mormon. He said, “No.” “Well, it will be my pleasure to send you a copy, and from it you will learn that the forefathers of the American Indians came from Jerusalem.” “Well,” he said, “that explains the mystery; I am much obliged for the book.” Now, the one thing for us to do, as Latter-day Saints, is to be loyal, to be true, to be patriotic, to be honest with God; then we need have no fear of what the world may say about us. We have the truth, and we know it, thank God; we know it, though the world may not know it. Let us follow the admonition of the Savior, and let our light so shine that other men seeing our good deeds shall glorify God.” ELDER HEBER J. GRANT 79th Annual Conference of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter- day Saints April 4th, 5th, and 6th, 1909, page 111-113

“I would say to the Lamanites, if I could speak to them understandingly, that you are also a branch of the house of Israel, and chiefly of the house of Joseph, and your forefathers have fallen through the same examples of unbelief and sins, as have the Jews, and you, as their posterity, have wandered in sin and darkness for many generations; and you, like the Jews, have been driven and trampled under the foot of the Gentiles, and put to death through your wars with each other, and with the white man, until you are almost destroyed. But there is still a redemption and salvation for a remnant of you in the latter days.” History of His Life and Labors By Wilford Woodruff

AFFINITY WITH THE JEWS

Among the early authorities cited, to show that the American Indians are descendants from the Israelites, Mr. Adair seems to be the principal one, and since his time, all writers who have favored his views, refer with unreserved confidence to the evidence furnished by him to this end.

Among the early authorities cited, to show that the American Indians are descendants from the Israelites, Mr. Adair seems to be the principal one, and since his time, all writers who have favored his views, refer with unreserved confidence to the evidence furnished by him to this end.

“One of the earnest writers in support of this theory in later times, is Rev. Ethan Smith, of Poultney, Vt , as shown in his book entitled “ View of the Hebrew, or the Tribes of Israel in America,” published in 1825, wherein he undertakes to prove, citing Mr. Adair and others, that the American Indians are descendants from the Lost Tribes of Israel.

Mr. Smith sums up the arguments of Mr. Adair that the natives of this continent are of the ten tribes of Israel, to the following effect: 1. Their division into tribes. 2. Their worship of Jehovah. 3. Their notions of a theocracy. 4. Their belief in the administration of angels. 5. Their language and dialects. 6. Their manner of counting time. 7. Their prophets and high priests. 8. Their festivals, fasts and religious rites. 9. Their daily sacrifice. 10. Their ablutions and anointings. 11. Their laws of uncleanliness. 12. Their abstinence from unclean things. 13. Their marriage, divorces and punishments of adultery. 14. Their several punishments. 15. Their cities of refuge. 16. Their purifications and preparatory ceremonies. 17. Their ornaments. 18. Their manner of curing the sick. 19. Their burial of the dead. 20. Their mourning for the dead. 21. Their raising seed to a deceased brother. 22. Their change of names adapted to their circumstances and times. 23. Their own traditions; the account of English writers ; and the testimonies given by Spaniards and other writers of the primitive inhabitants of Mexico and Peru.

Many of those who contend for Jewish origin of the American Indian insist that evidence of this fact is found in the languages of the Indians, which appear clearly to have been derived from the Hebrew. This is the opinion expressed by Mr. Adair, in which Dr. Edwards having a good knowledge of some of the Indian languages, concurs and gives his reasons for believing this people to have been originally Hebrew.

The languages of the Indians and of the Hebrews, he remarks, are both found without prepositions, and are formed with prefixes and suffixes, a thing not common to other languages; and he says that not only the words, but the construction of phrases in both are essentially the same. The Indian pronoun, as well as other nouns, he remarks, are manifestly from the Hebrews. The Indian laconic, bold, and commanding figures of speech, Mr. Adair notes as exactly agreeing with the genius of the Hebrew language.” Photograph (Left) of Elijah M. Haines, Illinois politician from Lake County and former Speaker of the Illinois House. Chapter IV Affinity with the Jews

(Below) Quote from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

American Indians

During the century before the Church was organized, the American Indian population in North America declined by about four hundred thousand as a result of warfare, exposure to disease, and the disruption of Indigenous economies caused by new settlers from Europe. At the same time, the European American population grew by over five million. In 1800 most colonial settlements remained within five hundred miles of the Atlantic Coast, but white settlers soon pressed westward across North America. This expansion led to tense encounters between Indians and white settlers.

By the early 1800s, Indian nations had engaged in centuries of trade, diplomacy, military alliances, and conflicts with European American settlers, and many tribes had signed treaties guaranteeing access to territory and resources. But in 1830 the United States Congress passed a law that permitted the removal of various tribes to territories west of the Mississippi River. Protestant churches sponsored missions to the displaced Native groups, hoping that gospel preaching would improve Indian relations. But Indian removal caused immense disruption and suffering and led to further conflict.

Indian-Mormon Encounters in the 1830s and 1840s

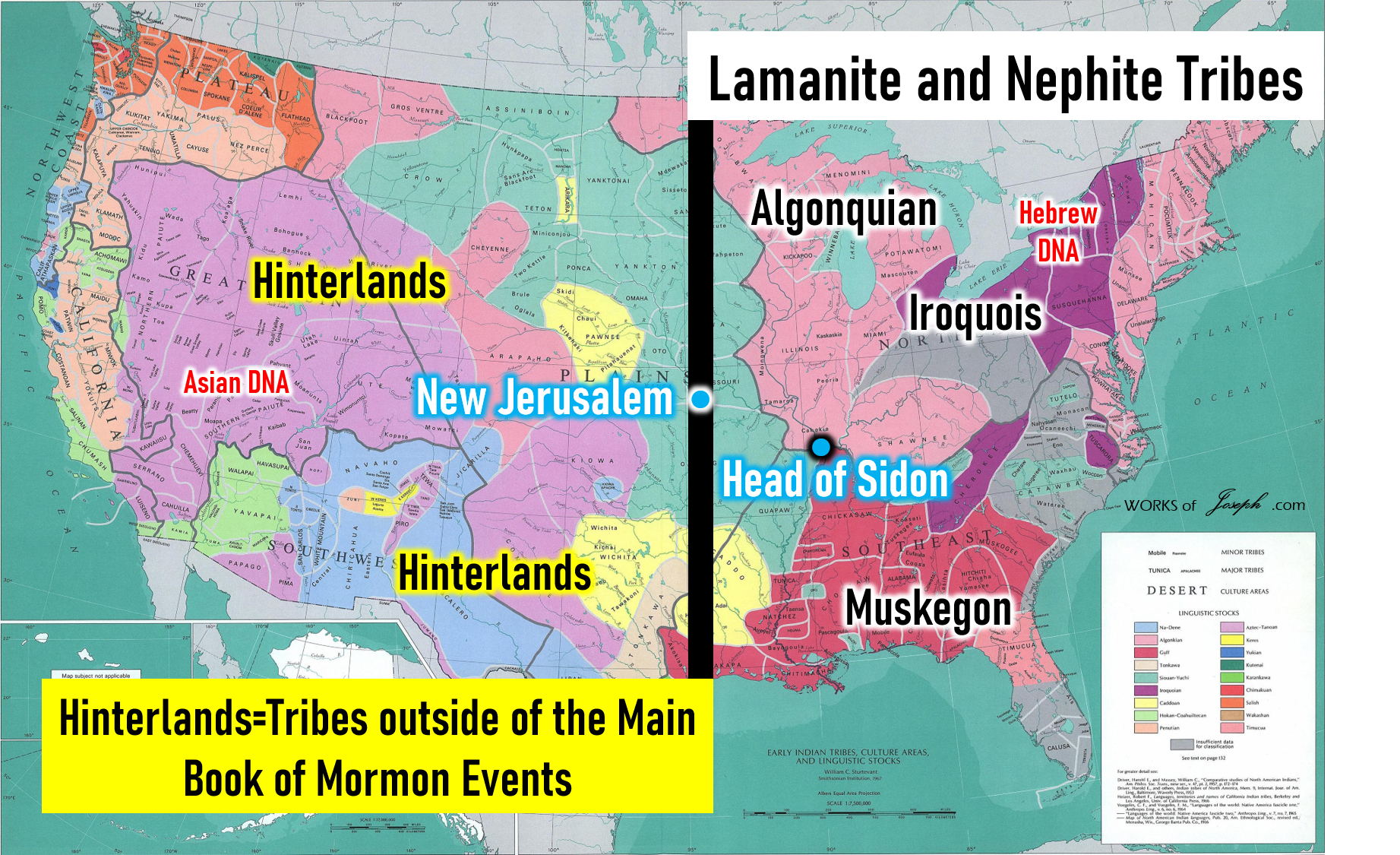

The Book of Mormon was published the same year the Indian Removal Act passed. It gave Church members a different perspective on the past history and future destiny of American Indians. The early Saints believed that all American Indians were the descendants of Book of Mormon peoples, and that they shared a covenant heritage connecting them to ancient Israel. They often held the same prejudices toward Indians shared by other European Americans, but Latter-day Saints believed Native Americans were heirs to God’s promises even though they now suffered for once having rejected the gospel. This belief instilled in the early Saints a deeply felt obligation to bring the message of the Book of Mormon to American Indians.

Within months of the founding of the Church in 1830, Latter-day Saint missionaries journeyed to Indian Territory, on the borders of the United States. Parley P. Pratt reported that William Anderson (Kik-Tha-We-Nund), the leader of a group of Delaware (Lenape) who had relocated to the area near Independence, Missouri, warmly received the missionaries, and an interpreter told Oliver Cowdery that the “chief says he believes every word” of the Book of Mormon. However, a government agent soon barred them from further evangelizing among Indians in the area because they had not secured proper authorization. Latter-day Saint interactions with American Indians remained sparse for the next few years, though Pratt and others still spoke of a day when Indians would embrace the Book of Mormon.

Joseph Smith preaching to American Indians.

Amid troubles in Missouri during the 1830s, Church leaders were cautious about contact with local Native groups, having been accused by their enemies of using missionary work to cultivate sedition among the Indians. During the 1840s, Joseph Smith and the First Presidency sent missionaries to the Sioux (Dakota), Potawatomi (Bodéwadmi), Stockbridge (Mahican), and other Indian peoples residing in Wisconsin and Canada. Delegations from the Sauk (Asakiwaki) and Fox (Meskwaki) tribes met in Nauvoo with Joseph Smith, who told them of the Book of Mormon and plans to raise up a New Jerusalem. Two years later, Potawatomi leaders asked Joseph and the Mormons to lend aid and join an alliance of confederated tribes. Joseph declined but assured them the Book of Mormon could light the way toward peaceful relationships. After Joseph’s death, the Council of Fifty, under Brigham Young’s leadership, discussed a broader alliance with Indian nations but ceased diplomatic efforts in 1846 in order to organize the Saints’ migration west.

Utah’s Native Peoples and the Latter-day Saint Pioneers

As Church President, territorial governor, and territorial superintendent of Indian affairs, Brigham Young pursued a peace policy to facilitate Mormon settlement in areas where Indians lived. Latter-day Saints learned Indian languages, established trade relations, preached the gospel, and generally sought accommodation with Indians. Peaceful accommodation between Indians and Latter-day Saints was both the norm and the ideal. But, despite Brigham Young’s constant effort to broker lasting agreements, his peace policy emerged unevenly and was inconsistently applied. These two cultures—European and American Indian—had vastly different assumptions about the use of land and property and did not understand each other well. These misunderstandings led to friction and sometimes violence between the peoples.

The two largest clashes between Latter-day Saints in Utah and local Indian groups later came to be known as the Walker War (1853–54) and the Black Hawk War (1865–72). They began as skirmishes between Mormon militias and principally Ute Indians that escalated into larger-scale conflicts. Violence between Mormons and Indians abated as disease and starvation severely reduced Indigenous populations living in the Intermountain West and United States federal action confined many Indians to reservations.

Indian Missions and Student Programs

Despite intermittent conflict, Church leaders remained committed to bringing the message of the Book of Mormon to Native Americans and established proselytizing missions and farms. These efforts introduced the gospel and provided education and food for Indians in Utah and Arizona. Missionaries during the second half of the 19th century visited Catawba (Yeh Is-Wah H’reh), Goshute (Kutsipiuti), Hopi (Hopituh Shi-nu-mu), Maricopa (Piipaash), Navajo (Diné), Papago (Tohono O’odham), Pima (Akimel O’otham), Shoshone (Newe), Ute (Nunt’zi), and Zuni (A:shiwi) peoples forced by settler expansion to live on Indian reservations scattered throughout the American West. Thousands of northwestern Shoshones in the 1870s were baptized and eventually formed the Washakie Ward, which was led by the first American Indian bishop in the Church, Moroni Timbimboo. Rather than move to reservations, many Utes from central Utah settled in Indianola in Sanpete County, where they built up a vibrant branch and a Relief Society, with an Indian woman serving in the presidency. Over 1,200 Papago, Pima, and Maricopa Indians in southern Arizona joined the Church in the 1880s, establishing a ward that later contributed to the building and dedication of the Mesa Arizona Temple. In South Carolina, most of the Catawba Nation received baptism. About 65 years later, Catawba chief Samuel Taylor Blue spoke in general conference. “I have tasted the blessing and joy of God,” he testified. “I have seen the dead raised; I have seen the sick whom the doctors have given up, through the administration of the Elders they have been restored to life. My brothers and sisters, beyond a shadow of a doubt I know that this gospel is true.”

Chief Washakie (seated, center front) and other Shoshone men.

Latter-day Saint outreach to American Indians continued into the 1930s and 1940s with the expansion of missions in Arizona and New Mexico. These missions alerted Church leaders to adverse conditions on the Southwest Indian reservations, and they began to consider alternatives to direct proselytizing, feeling, as Spencer W. Kimball later expressed, an obligation to help their covenant siblings. In the 1950s a student placement program emerged in which Latter-day Saint families hosted Indian students during school semesters. In addition, Brigham Young University offered scholarships with the goal of increasing American Indian enrollment. By the time the Indian Student Placement Program came to a close around the year 2000, some 50 thousand American Indian students had been sponsored.

American Indians today continue to face difficulties as a result of centuries of conflict and displacement. Larry Echo Hawk, a member of the Pawnee Nation, former U.S. Assistant Secretary of the Interior for Indian Affairs, and current General Authority Seventy, spoke in 2007 of the challenges he and his ancestors have faced. “That is a painful history,” he stated, adding that “the pain was not limited to one generation.” Nevertheless, he found strength in the Book of Mormon’s promises and expressed his hope that America’s native peoples will live up to the vision articulated by President Spencer W. Kimball, becoming powerful leaders in their communities and nations.” https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/history/topics/american-indians?lang=eng

Church Resources