It is absolutely amazing that in over 53 years of life I had never heard of this amazing first book of the Smithsonian’s. Why didn’t our schools teach these things? Maybe I wasn’t paying attention but I doubt something this big could elude my parents, teachers and I. *Millions of earthworks made by an ancient North American people? How can they hide that? Or, how can people not teach of such a magnificent thing? It seems to me the Smithsonian hid this magnificent book, probably after they found out that it was teaching that ancient North Americans were more intelligent than they wanted us to believe. How many other artifacts in the Smithsonian are hid from us? Wayne May has been there in their basement and he verify’s that hundreds, probably thousands of artifacts are there, including a 9 foot skeleton.

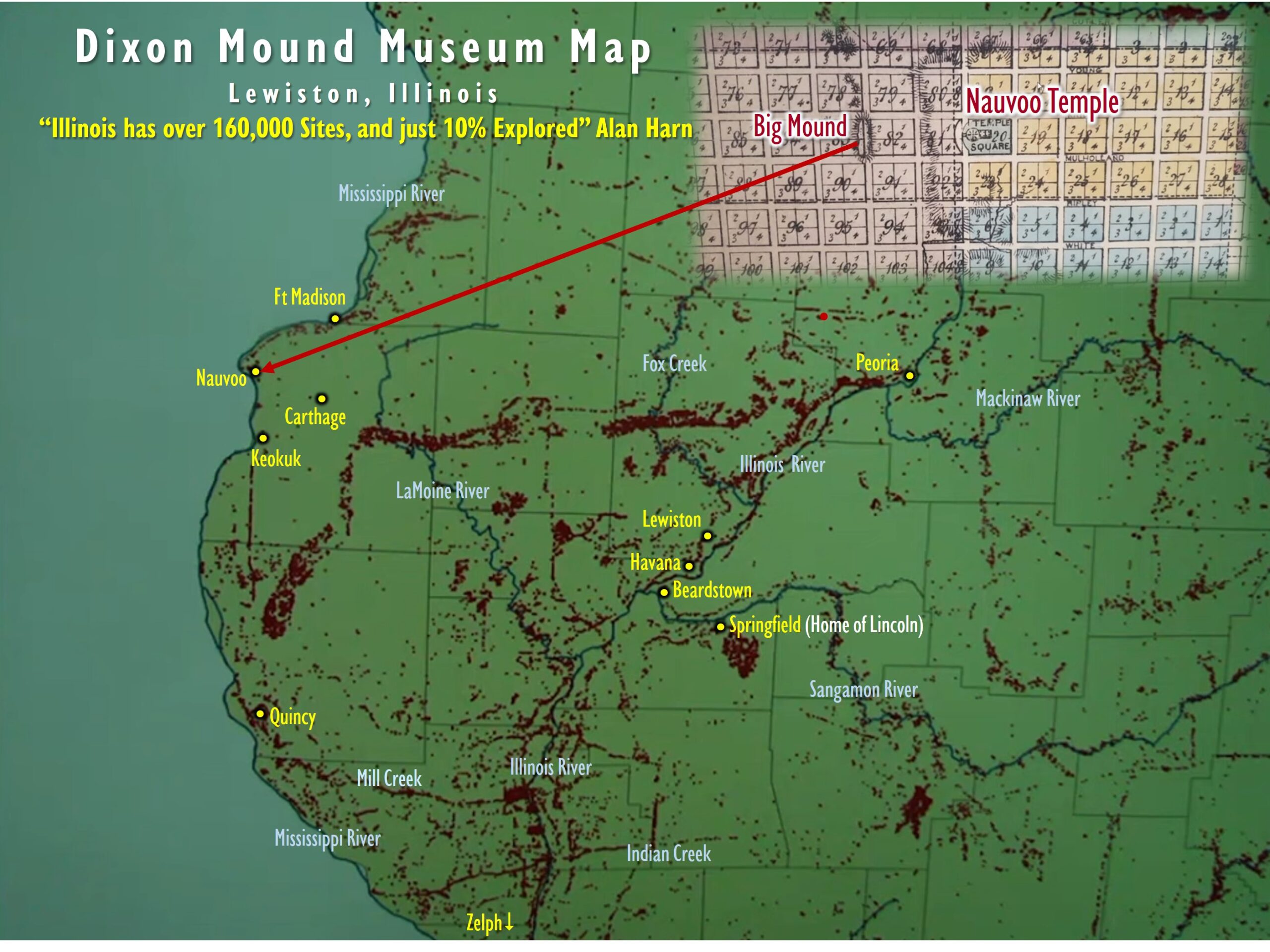

* “The most common question that is asked about mounds is, “How many exist?” In the 1800’s the Smithsonian sponsored many expeditions to identify mound sites across America. A map (shown above) was produced by Cyrus Thomas in 1894 in a Bureau of Ethnology book. They found approximately 100,000 mound sites, many with complexes containing 2 to 100 mounds. The figure of 100,000 mounds once existing— based on Cyrus Thomas map revealing 100,000 sites—is often cited by others, but that estimate is far, far too low. After visiting several thousand mounds and reviewing the literature, I am fairly certain that over 1,000,000 mounds once existed and that perhaps 100,000 still exist. Oddly, some new mound sites are discovered each year by archaeological surveys in remote areas. But in truth, a large majority of America’s mounds have been completely destroyed by farming, construction, looting, and deliberate total excavations” – Gregory L. Little, Ed.D., The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Native American Mounds & Earthworks, Eagle Wing Books, Inc., Memphis, TN [2009].

Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley

Early in the 19th century, as wagon trains streamed into the Ohio and Mississippi valleys, settlers came upon vast numbers of abandoned earthworks that they attributed to a sophisticated race of long-gone mound builders. Giving rise to often-loaded questions about human origins, the mounds and the artifacts found within them became the focus of early American efforts toward a science of archaeology. Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley (1848) was the first major work in the nascent discipline as well as the first publication of the newly established Smithsonian Institution. It remains today both a key document in the history of American archaeology and the primary source of information about hundreds of mounds and earthworks in the eastern United States, most now vanished. While adhering to the popular assumption that the builders could not have been the ancestors of the supposedly savage Native American groups still living in the region, the authors set high scientific standards for their time. Their work provides insight into some of the conceptual, methodological, and substantive issues that archaeologists still confront. The book includes numerous maps, plates, and engravings.

“The Smithsonian Institution was established with funds from James Smithson (1765-1829), a British scientist who left his estate to the United States to found “at Washington, under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge.” On August 10, 1846, the U.S. Senate passed the act organizing the Smithsonian Institution, which was signed into law by President James K. Polk.”

Congress authorized acceptance of the Smithson bequest on July 1, 1836, but it took another ten years of debate before the Smithsonian was founded! Once established, the Smithsonian became part of the process of developing an American national identity—an identity rooted in exploration, innovation, and a unique American style. That process continues today as the Smithsonian looks toward the future.”

Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley (full title Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley: Comprising the Results of Extensive Original Surveys and Explorations) (1848) by the Americans Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis is a landmark in American scientific research, the study of the prehistoric indigenous mound builders of North America, and the early development of archaeology as a scientific discipline. Published in 1848, it was the Smithsonian Institution’s first publication and the first volume in its Contributions to Knowledge series.[1] The book had 306 pages, 48 lithographed maps and plates, and 207 wood engravings. Smithsonian

Lost American Antiquities: A Hidden History – Silencing the Ancient Mound Builders

by Steven E. Smoot

CHAPTER 8

“The Smithsonian had much riding on the Squier and Davis report, as there was much Congressional interest in continuing the investigation into the Mound Builders. Though today their report is not commonly known, they did not come about as the first publication of the Smithsonian in a vacuum. In the middle of the 1800s there were many men of science who were advancing competing works.

Rather than providing answers, the Squier and Davis report and research would raise even more questions as to the origin of the ancient Mound Builders. The artifacts found would spark the imagination of many Americans of many different interests, who were keen to learn more about the antiquities of America and of the mysterious people who had left such magnificent artifacts and earthworks.

Included in that group of interested parties was the newly formed Smithsonian Institution, which had accepted the work of Squier and Davis. The said work included a large collection of survey maps with intriguing descriptions of ancient artifacts that provided insight into these ancient cultures—making their choice of Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, as the first-ever publication issued by the Smithsonian Institution on any subject, a very interesting selection.

In the 1998, republication of Ancient Monuments by the Smithsonian, David J. Meltzer stated: “All this was riding on a book devoted to the questions of the origin, antiquity, and identity of the Mound Builders.”48 In the wake of Squier and Davis’s report, questions were still looming about who the people were that built such amazing earthwork structures and mounds, which provided evidence of an understanding of higher mathematics, advanced engineering, and the cosmos. The view at the time was that the “mound construction was widely and popularly attributed to a race of mound-builders, who no longer existed or at least no longer existed where and as they had earlier.”49

E.G. Squire Bottom

Even after the publication of this record by the Smithsonian, there continued to be questions raised. Were the Mound Builders the American Indians, who many in that day believed to be a savage culture, or were they a lost race that once existed and then through war, disease, and migration had mysteriously disappeared? Meltzer states; “There was considerable speculation, among antiquarians no less than others, about who the Mound Builders were, where they had come from and when and where they had disappeared to…Nor was it clear how the Mound Builders related to living Native Americans: Were they linked as ancestors and descendants?”50 Or were they a separate culture or a mixture of cultures, and were they savage, barbaric or civilized?

Squier’s report still stands as one of the most significant works ever produced looking into these ancient North American mound-building cultures. It was hailed around the world as a “Great American Work”, shortly after being turned over to the Smithsonian in May 1847, not long after the Smithsonian’s founding by Congress on August 10, 1846. The Board of Regents for the Smithsonian Institution was composed of politicians and elected officials of the U.S. government who themselves harbored nationalistic aspirations for the fledgling institute. It was at this time that the final arrangements for the publication of Squier and Davis’s work as the first volume of the Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge was worked on by a committee of the American Ethnological Society who recommended its publication. An advertisement in the “Literary World” hailed “Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley a Great American Work.51

This spiral bound over sized book contains a complete set of 48 of the plates from the book, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley by the Smithsonian’s E.G. Squier and E.H. Davis from their original surveys. These reproductions have been enlarged 120% from the original size for greater detail. They include such works as those of Newark, Chillicothe and Marietta, Ohio, the Great Circle & Octagon, Fort Ancient, Fort Hill, Serpent Mound, and “the Cross.”

“Such was the consensus on the Squier-Davis researches until the founding of the Smithsonian’s Bureau of American Ethnology in 1879.” [Under the direction of John Wesley Powell, who would find it difficult to challenge their report given.] “Indeed, the reverence with which the views of Squier and Davis work were generally received placed an enormous burden on the next generation of archaeologists who labored to overthrow the “lost Race” theory.” However, Powell as director, along with “Henry W. Henshaw of the Bureau of Ethnology began the task of debunking the honored authors’ (Squier and Davis) in 1880.” Also employed by Powell was “Cyrus Thomas, the bureau’s director of mound explorations, who rejected the functional assumptions of the authors’ ‘imperfect and faulty’ classification of mounds enclosures in favor of a less theoretical nomenclature.”52

Squier and Davis’s 1848 report was heralded as a ‘monumental work’ for over thirty years, but in the late 1800s Squier began to experience a more organized criticism of their work, with a lot of it stemming from the Bureau of Ethnology, under its founder John Wesley Powell. Powell would take the lead in working to overthrow some of the findings and claims surrounding the origin of the Mound Builders. This newly organized bureau of the Smithsonian would go on to re-define many of the artifacts that had been associated with America’s mound building cultures. The Bureau’s work would serve to discredit some of Squier’s previous assessments, which would work to multiply the personal tragedies that would plague Squier in his later life. This riff between Squier and the Bureau of Ethnology at the Smithsonian resulted in a number of his works never being printed and, in some cases, never even finished. Squier was diagnosed in later life with a mental illness and was committed to a mental institution, where he was imprisoned for over a decade of the last years of his life.

Even though much of the institutional criticism came concerning his works in the 1880-90s, there were some who began to question and to criticize his work shortly after Ancient Monuments publication in 1848, as Henshaw working under Powell would be critical of some of his elucidations of his findings as ‘theoretical.’ Thus, they requested of Squier’s to do a new report, taking a renewed look at what artifacts were to be found in the State of New York.

Grave Creek Mound surrounded by embankments

Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, 1848, Squier and Davis, Plate XXVII

In his comparative studies, Squier believed that he was making a great breakthrough. “He regarded the results of those investigations to be “truly remarkable” and again stated his certainty that once completed they would bring new evidence to bear upon “the origin and antiquity of the American race.”53

In sharing his finding with Henry, Squier stated: I speak with almost absolute certainty, when I say that I have the key to the whole system of our aboriginal religion. North and South, and that I have identified not only the original purpose of the imposing monuments of Central America, but the very nature of the worship and the divinities to which they were dedicated.54

Squier’s growing interest in pursuing these investigations beyond casual mention had prompted Henry [then head of the Smithsonian] to eliminate certain “theoretical matter” from the Squier-Davis manuscript just prior to its printing, Squier complained to Samuel George Morton in September 1848 that the work had been “emasculated” by Henry’s heavy-handed editing. He declared that he would thereafter remain free and clear of all “entangling alliances” with institutions: “I have danced to one turn in fetters—for the first and last time.” Henry further angered Squier due to his reluctance to underwrite the cost of extending Squier’s investigations into other portions of the Mississippi Valley…He was determined that once his business with the Smithsonian was concluded “our paths will diverge at a very large angle.”…Squier’s attitude toward Henry and the Smithsonian was unfortunate. His reputation as an archaeologist rests squarely upon the originality and disciplined nature of his two monographs published in the Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge.55

It was after Squier had complained of the theoretical material that Henry had removed from his 1848 report, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. After which he stated, his unwillingness to have any further dealings with Henry and the Smithsonian. He would later agree, to accept an offer to be rehired to do an eight week study, looking into the ancient monuments of New York, stating: “I gladly availed myself of the jointly liberality of the Smithsonian Institution and the Historical Society of New York, to undertake its investigation.”56 Even though he knew that his work would be under close scrutiny and the heavy-handed editing by the Smithsonian. Needing the money, he accepted employment, and went to work looking at the ruins found in the State of New York. He presented his second report, Aboriginal Monuments of New York, published by the Smithsonian, in 1849.

Squier referring to his work in his 1849 report, stated: “In the short period of eight weeks devoted to the search, I was enabled to ascertain the localities of not less than one hundred ancient works and to visit and make surveys of half that number.”… “In respect to the number of these remains, some estimate may be formed from the fact that, in Jefferson [c]ounty alone, fifteen [e]nclosures were found, sufficiently well preserved to admit of being traced throughout.”57

Yet even though he completed this record, he decided that he was displeased with how the Smithsonian dealt with his research. He decided to write and publish his own unedited book using some of the research he had done in Aboriginal Monuments of New York 1849 and also some information from his 1848 work, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. He would title his independent book, Antiquities of New York with a Supplement on the Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, and would publish it in Buffalo, New York in 1851.58

In the Supplement on the Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, given in his 1851 book, Antiquities of New York, he would impart observations on what would be considered contentious topics for discussion, including the following chapters: Inclosures [Enclosures] for Defense, Sacred Inclosures, Mound of Sepulture, of Sacrifice, Implements, Ornaments and Sculptures.

Squier, in writing Antiquities of New York separate from Davis and the Smithsonian involvement, would decide to use some of the original printing plates, from Ancient Monuments and Aboriginal Monuments of New York in his self published, Antiquities of New York. In it he would state, that “many evidences of ancient labor and skill are to be found in the western parts of New York and Pennsylvania upon the upper tributaries of the Ohio, and along the shores of Lakes Erie and Ontario. Here we find a series of ancient earth-works, intrenched [sic] hills, and occasional mounds, or tumuli, concerning which history is mute, and the origin of which has been regarded as involved in impenetrable mystery.”59

Squier went on to say: “De Witt Clinton, whose energetic mind neglected no department of inquiry, read a brief memoir upon the subject before the ‘Literary and Philosophical Society of New York,’ which was published in pamphlet form, at Albany, in 1818. Mr. Clinton in his memoir did not profess to give a complete view of the matter; his aim being, in his own language, ‘to waken the public mind to a subject of great importance, before the means of investigations were entirely lost.”60

“He [Squier] also discusses the symbolism of temples. Those comparisons further document his interest in developing cross-cultural analogies as a means of interpreting archaeological evidence and in tracing supposed universals in the psychological development of man. Squier eventually elaborated those interests in The Serpent Symbol, where he made his most systematic and comprehensive comparison of the mind of man as illustrated by religious ideas, symbols, and customs from around the globe. Everywhere he looked in his study of religious symbolism he saw further evidence of the psychic unity of man.”61

Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, 1848, Squier and Davis, Plate XVIII

Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, 1848, Squier and Davis, Plate XXI Symbolic reoccurring giant Earthworks

End Notes

48 Squier and Davis, 1848, 1

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid, 2

51 Ibid, See 21,35

52 See Barnhart; Ephraim George Squier and the Development of Am. Anthropology; 100, ref. 363. Also see: Henshaw, Animal Carvings form the Mounds of the Mississippi Valley, 123-66 and Cyrus Thomas, The Circle, Square and Octagonal Earthworks of Ohio-Washington DC: Gov. Printing Office, 1889—On the correction of the Squier and Davis Report, see: Thomas, Bureau of Ethnology Twelfth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology, 1890-91 454-468 and 472-49. A defense of the survey; Stephen Denison Peet, American Antiquatian 12, no.2 1890: 116-117:

53 Barnhart, Ephraim George Squier and the Development of American Anthropology: 189

54 Ibid. 190

55 Ibid.

56 E. G. Squier: Antiquities of the State of New York: (Buffalo, Geo. H. Derby and Co. 1851) 10

57 Ibid. 11

58 Ibid. Introduction Page

59 Ibid. 8

60 Ibid 8

61 See: Barnhart. Ephraim George Squier and the Development of American Anthropology 190.

Description of sites across much of the Eastern United States

Ancient Monuments provides descriptions of sites across much of the Eastern United States. The hundreds of earthworks which Squire and Davis personally surveyed and sketched were located primarily in and around Ross County in southern Ohio. This area includes Serpent Mound, Fort Ancient, Mound City , Seip Earthworks and Newark Earthworks.

This is an actual reprint of the very first publication of the Smithsonian Institution and comprises the results of extensive original surveys and explorations in 1848. It contains the earliest study of the remains of the Moundbuilders whose civilization thrived in the Heartland of North America from 500 B.C. to 400 AD – Book of Mormon time frames! A ‘must read’ for anyone desiring to learn more about the Nephites from one of the earliest sources. 306 page softbound. https://bookofmormonevidence.org/bookstore/product/ancient-monuments-of-the-mississippi-valley-1848-book/

Ancient Cities of the Mississippi Valley

From JosephKnew.com

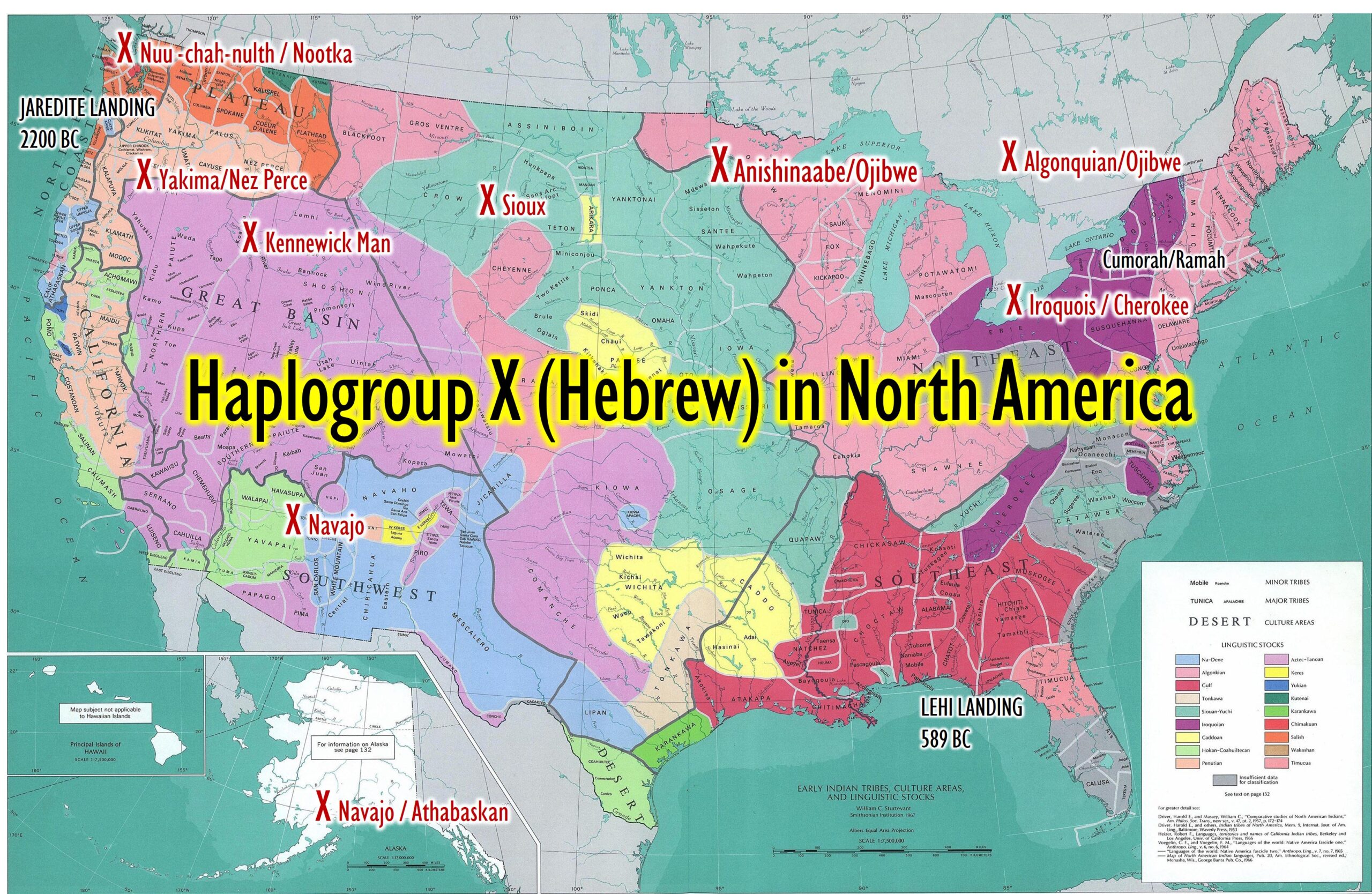

For students of the Book of Mormon, one of their findings is of particular interest. On a site called the East Fork Works (Sometimes called “Gridiron” or “Hebrew Works”) in Clermont County, Ohio, Squire and Davis found the remains of a large complex or city laid out in a very particular manner.

This “Gridiron” (on the right in the above image) was laid out as a walled city with detailed formations. As you can see in the over-lay below, one section of the city was laid out in the shape of a menorah.

Above the menorah section of the city, we can see a Jewish clay lamp. (Below)

Also visible in the design and construction of the city are two ancient and important symbols, the compass and the square. See Below

The Hopewell culture, of which this city is a part, dates from 100 B.C. to 600 A.D. Many of their structures and the artifacts found in and around them indicate there was a strong Hebrew influence. This Hebrew culture such as we find in the East Fork site can be explained in the Book of Mormon. A group left Israel in 600 B.C., traveled across the ocean, landed in North America, formed governments, built cities, and about 70 B.C. built, in a particular manner, the great City of Lehi.

“And it came to pass that the Nephites began the foundation of a city, and they called the name of the city Moroni; and it was by the east sea; and it was on the south by the line of the possessions of the Lamanites.

“And they also began a foundation for a city between the city of Moroni and the city of Aaron, joining the borders of Aaron and Moroni; and they called the name of the city, or the land, Nephihah.

“And they also began in that same year to build many cities on the north, one in a particular manner which they called Lehi, which was in the north by the borders of the seashore.” (The Book of Mormon, Alma 50:13-15 – emphasis added)

Whether the city found in Clermont County, Ohio is the City of Lehi, or just another Hopewell city, the Hebrew influence is clear. Combined with evidence from other sites throughout North America, the East Fork site confirms that the early inhabitants of this continent were sophisticated, educated, and religiously devoted.

Copyright © 2014 by Energy Media Works LLC