Why do many insist that the final battle of the Nephites and Lamanites didn’t happen at the one and only Hill Cumorah in New York? Many yell the words, “It’s a clean hill”, meaning there are no arrowheads found there, or they say, “where are all the bones?” Bones from 1,400 years ago that weren’t even buried? No breastplates or head-plates? Ever hear of spoils of the war. Too small of a hill? The final battles didn’t happen just on a little hill, but in the Land of Cumorah. See Mormon 6:2. Oliver Cowdery said in Letter VII it was the hill of the final battles. Good enough for me. It makes sense. I believe the final battles happened in the Land of Cumorah, near the hill.

Many thanks to Wayne May’s and some of his collection of information about bones found near Hill Cumorah. I ask people who believe in the Mesoamerican theory if they have found bones in their many possible locations in Mesoamerica including, Huimanguillo Tabasco, Yaxchilan, Palenque, Chiapa de Corzo, Quirigua, Santa Rosa, El Cayo, plus many other possible locations for Cumorah as they claim? See map above to see the suggested locations for Cumorah from the Mesoamerican perspective.

CHARACTER OF INDIAN DEFENSES

From ScienceViews.com

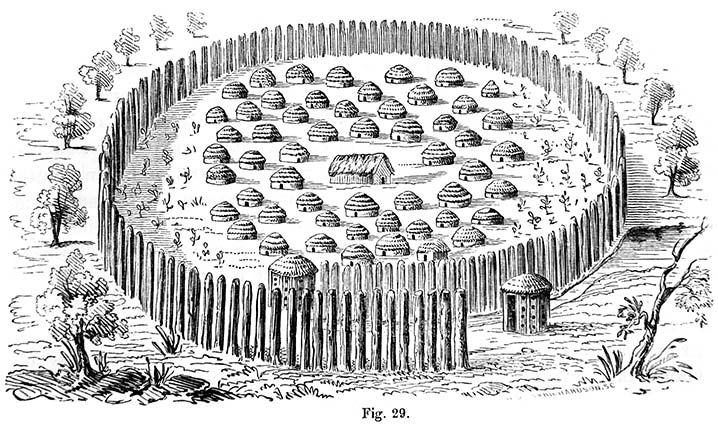

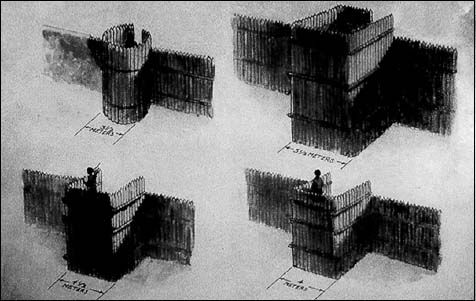

THE fortifications of the savage or hunter tribes of North America are uniformly represented to have been constructed of rows of pickets, surrounding their villages, or enclosing positions naturally strong and easy of defence. The celebrated stronghold of the Narragansetts in Rhode Island, destroyed in 1676 by the New England colonists under Winthrop and Church, was an elevation of five or six acres in extent, situated in the centre of a swamp, and strongly defended by palisades. It was of extraordinary size, and enclosed not far from six hundred lodges.

Of like character was the fort of the Pequots, on the Mystic River, in Connecticut, destroyed by Captain Mason. According to Hackluyt, the towns of the Indians on the St. Lawrence were defended in a similar manner. The first voyagers describe the aboriginal town of Hochelaga, now Montreal, as circular in form, and surrounded by three lines of palisades. Through these there was but a single entrance, well secured by stakes and bars; and upon the inside of the defence, were stages or platforms, upon which were placed stones and other missiles, ready for use, in case of attack. The town contained about fifty lodges.—(Hackluyt, Vol. III., p. 220.)

Charlevoix observes, that “the Indians of Canada are more expert in erecting their fortifications than in building their houses.” He represents that their villages were surrounded by double and frequently by triple rows of palisades, interwoven with branches of trees, and flanked by redoubts.—(Canada, Vol. II., p. 128.) Champlain also describes a number of fortified works on the St. Lawrence, above Trois Riviéres, which “were composed of a number of posts set very close together.” He also speaks of “forts which were great enclosures, with tiers joined together like pales,” within which were the dwellings of the Indians.—(Purchas, Vol. IV., pp. 1612, 1644.) Says La Hontan, “their villages were fortified with double palisades of very hard wood, which were as thick as one’s thigh, fifteen feet high, with little squares about the middle of the courtines (curtains).—(Vol. II., p. 6.) The Indians on the coasts of Virginia and North Carolina are described as possessing corresponding defences. “When they would be very safe,” says Beverly, “they treble the pales.”—(Hist. Vir., p. 149. See also Amidas and Barlow, in Pink., Vol. XII., p. 567; Heriot, ib. p. 603; Lafitau, Vol. III., p. 228, etc. etc.)

Among the Floridian tribes, the custom of fortifying their villages seems to have been more general than among the Indians of a higher latitude. This may readily be accounted for from the fact that they were more fixed in their habits, considerably devoted to agriculture, and less averse to labor than those of the north. The chronicler of Soto’s Expedition speaks of their towns as defended by “strong works of the height of a lance,” composed of “great stakes driven deep in the ground, with poles the bigness of one’s arm placed crosswise, both inside and out, and fastened with pins to knit the whole together.” Herrara, in his compiled account of the same expedition, has the following confirmation. “The town of Mabila or Mavila (Mobile) consisted of eighty houses seated in a plain, enclosed by piles driven down, with timbers athwart, rammed with long straw and earth between the hollow spaces, so that it looked like a wall smoothed with a trowel; and at every eighty paces was a tower, where eight men could fight, with many loop-holes and two gates. In the midst of the town was a large square.”—(Hist. America, Vol. V., p. 324.) Du Pratz also gives a corresponding account of the defences of the Natchez and neighboring tribes. “Their forts are built circularly, of two rows of large logs of wood, the logs of the inner row being opposite to the joinings of those of the outer row. These logs are about fifteen feet long, five feet of which are sunk in the earth. The outer logs are about two feet thick, the inner ones half as much. At every forty paces along this wall, a circular tower juts out, and at the entrance of the fort, which is always next the river, the two ends of the wall pass beyond each other, leaving a side opening. In the middle of the fort stands a tree, with the branches lopped off within a short distance of the trunk, and this serves as a watch-tower.—(Hist. Louisiana, p. 375.) The sub- joined description and illustrative engraving, copied from De Bry, no doubt convey a correct idea of the character of the Floridian defenses.

“The Indians build their towns in this wise. Having made choice of a spot near a running stream, they level it off as even as they can. They next draw a furrow of the size of the intended town in the form of a circle, in which they plant large round stakes, twice the height of a man, and set closely together. At the place where the entrance is to be, the circle is somewhat drawn. in, after the fashion of a snail-shell, making the opening so narrow as not to admit more than two at a time. The bed of the stream is also turned into this entrance. At the head of the entrance, a small round building is usually erected; within the passage is placed another. Each of them is pierced with slits and holes for observation, and is handsomely finished off after the manner of the country. In these guardhouses are placed those sentinels who can scent the trail of enemies at a great distance. As soon as their sense of smelling tells them that some are near, they hasten out, and, having found them, raise an alarm. The inhabitants on hearing the shouting immediately fly to the defence of the town, armed with bows, arrows, and clubs.

“In the middle of the town stands the king’s palace, sunk somewhat below the level of the ground, on account of the heat of the sun. Around it are ranged the houses of the nobles, all slightly covered with palm branches; for they make use of them only during nine months of the year, passing, as we have said, the other three months in the woods. When they return, they take to their houses again; unless, indeed, they have been burnt down in the meantime by their enemies, in which case they build themselves new ones of similar materials. Such is the magnificence of Indian palaces.”

Among the Indians to the westward of the Mississippi, particularly among the Mandans and kindred tribes, a somewhat different system of defence prevailed. The serpentine courses of the rivers, all of which have here high steep banks, leave many projecting points of land on elevated peninsulas, protected on nearly all sides by the streams, and capable, with little artificial aid, of being made effective for defensive purposes. Mr. Catlin describes the principal village of the Mandans, while that remarkable tribe existed, as protected upon three sides by the river, and upon the fourth “by a strong picket, with an interior ditch, three or four feet in depth.” The picket was composed of timbers a foot or more in diameter and eighteen feet high, set firmly in the ground, at a sufficient distance from each other to admit guns to be fired between them. The warriors stationed themselves in the ditch during an attack, and were thus almost completely protected from their assailants. These practices seem, however, to be of comparatively late introduction.—(N. A. Indians, Vol. I., p. 81.)

Brackenridge (Views of Louisiana, p. 242) mentions the ruins of an Indian town upon the Missouri River, fifty miles above the mouth of the Shienne. The spot was marked by “great piles of Buffalo bones and quantities of earthen-ware. The village appeared to have been scattered around a kind of citadel or fortification, enclosing from four to five acres, in an oval form.” The earth was thrown up about four feet, and a few of the palisades were remaining. The Shienne River is 1300 miles above the mouth of the Missouri. Lewis and Clark also mention a number of remains of Indian fortifications of like character, but it is to be observed that they distinguish between them and the larger and more imposing ancient works which fell under their notice in the same region. They describe an abandoned village of the Riccarees, called Lahoocat, which was situated in the centre of Goodhope Island. It contained seventeen lodges, surrounded by a circular wall, and is known to have been occupied in 1797.—(Exp., p. 72.) They also mention the remains of a deserted village, erected by Petit Arc or Little Bow, an Omahaw chief, on the banks of a small creek of the same name, emptying into the Missouri. It was surrounded by a wall of earth about four feet high.—(Exp., p. 41.) A circular work of earth, formerly enclosing a village of the Shiennes, was noticed by these explorers, a short distance above the mouth of the Shienne River.—(Exp., p. 80.) The ancient villages of the Mandans, nine of which were observed in the same vicinity, within a space of twenty miles, were indicated by the walls which surrounded them, the fallen heaps of earth which covered the huts, and by the scattered teeth and bones of men and animals.—(Exp., p. 84.) Another defensive work, probably designed for temporary protection, was observed by these gentlemen in the vicinity of the mouth of the Yellowstone. “It was built upon the level bottom, in the form of a circle, fifty feet in diameter, and was composed of logs lapping over each other, about five feet high, and covered on the outside with bark set upright. The entrance was guarded by a work on each side of it, facing the river.” These entrenchments, they were informed, are frequently made by the Minaterees and other Indians at war with the Shoshonees, when pursued by their enemies on horseback.—(Exp., p. 622.) Lieut. Fremont found similar constructions in the vicinity of the Arkansas. A much more feasible method of protection, under such circumstances, is mentioned by Pike. He states that the Sioux, when in danger from their enemies in the plains, soon cover themselves by digging holes with their knives, and throwing up small breastworks.—(Exp., p. 19.) They are represented as being able to bury themselves from sight, in an incredibly short space of time.

The numerous traces upon the Missouri of old villages occupying similar positions, and having evidently been defended in a like manner with those above described, place it beyond doubt that this method of fortification was not of recent origin among those Indians. Mr. Catlin mentions that there are several ruined villages of the Mandans, Minaterees and Riccarees, on the banks of the river, below the towns then occupied, which have been abandoned since intercourse became established with the whites.

Prince Maximilian notices a feature in the defences of the Mandan village of Mih-tutta-hang-kush, which does not seem to have been remarked by any other traveler. This village is represented to have consisted of about sixty huts, surrounded by palisades, forming a defence, at the angles of which were “conical mounds, covered with a facing of wicker-work, and having embrasures, completely commanding the river and plain.” In another place, however, our author adds, that these bastions were erected for the Indians by the whites.—(Travels in the Interior of North America, by Maximilian, Prince of Weid, pp., 173, 243.)

ANCIENT WORKS IN PENNSYLVANIA AND NEW HAMPSHIRE from ScienceViews.com

WITHOUT the boundaries of the State of New York, there are works composed of earth, closely resembling those described in the preceding pages. Among these may be named the small earth-works of Northern Ohio, which the author himself was at one time led to believe constituted part of the grand system of the mound builders.19 The more extensive and accurate information which he has now in his possession concerning them, as also concerning those of Western New York, has led to an entire modification of his views, and to the conviction that they are all of comparatively late date, and probably of common origin.

Some similar works are said to occur in Canada; but we have no account at all satisfactory concerning them. One is mentioned by Laing (Polynesian Nations, p. 109) upon the authority of a third person, as situated upon the summit of a precipitous ridge, near Lake Simcoe, and consisting of an embankment of earth, enclosing a considerable extent of ground. Mr. Schoolcraft also states that there are some ancient enigmatical walls of earth in the vicinity of Dundas, which extend several miles across the country, following the leading ridges of land. These are represented to be from five to eight miles in length, and not far from six feet high, with passages at intervals, as if for gates (Oneota, p. 326). Our knowledge concerning these is too limited to permit any conjecture as to their design.

In the State of Pennsylvania, there are some remains, which may be regarded as the “outliers” of those of New York. They are confined to the upper counties. Those in the Valley of Wyoming are best known. They have, however, been lately so much obliterated, that it is probable they can be no longer traced. One of the number was examined and measured in 1817 by a gentleman of Wyoming, whose account is published by Mr. Miner, in his “History of Wyoming.”

“It is situated in the town of Kingston, Luzerne county, upon a level plain, on the north side of Toby’s Creek, about one hundred and fifty feet from its bank, and about half’ a mile from its confluence with the Susquehanna. It is of an oval or elliptical form, having its longest diameter from northeast to southwest, at right angles to the creek. Its diameters are respectively 337 and 272 feet. On the southwest side appears to have been a gateway, twelve feet wide, opening towards the great eddy of the river into which the creek falls. It consisted of a single embankment of earth, which in height and thickness appears to have been the same on all sides. Exterior to the wall is a ditch. The bank of the creek upon the side towards the work is high and steep. The water in the creek is ordinarily sufficiently deep to admit canoes to ascend to the fortification from the river. When the first settlers came to Wyoming, this plain was covered with its native forests, consisting principally of oak and yellow pine; and the trees which grew upon the work are said to have been as large as those in any part of the valley. One large oak, upon being cut down, was found to be 700 years old. The Indians have no traditions concerning these fortifications; nor do they appear to have any knowledge of the purposes for which they were erected.”—(Miner’s History if Wyoming, p. 25.) Traces of a similar work existed on “Jacob’s Plains,” on the upper flats of Wilkesbarre. “It occupied the highest point on the flats, which in the time of freshets appears like an island in the sea of waters. In size and shape it coincides with that already described. High trees were growing upon the embankment at the period of the first settlement of the country. It is about eighty rods from the river, towards which opened a gateway; and the old settlers concur in stating that a well [cache ?] existed in the interior near the southern line. On the banks of the river is an ancient burial-place, in which the bodies were laid horizontally in regular rows. In excavating the canal through the bank bordering the flats, perhaps thirty rods south of the fort, another burial-place was disclosed, evidently more ancient, for the bones crumbled to pieces almost immediately upon exposure to the air, and the deposits were far more numerous than in that near the river. The number of skeletons are represented to have been countless, and the dead had been buried in a sitting posture. In this place of deposit no beads were found, while they were common in the other.”—(Miner’s History, p. 28.)

Near this locality, which seems to have been a favorite one with the Indians, medals bearing the head of the First George, and other relics of European origin, are often discovered.

Still further to the northwest, near the borders of New York, and forming an unbroken chain with the works of that State, are found other remains. One of these, on the Tioga River, near Athens, was ascribed by the Duke de Rochefoucauld to the French, in the time of De Nonville! He describes it as follows: “Near the confines of Pennsylvania, a mountain rises from the banks of the River Tioga, in the shape of a sugar loaf, upon which are to be seen the remains of some entrenchments. These are called by the inhabitants the ‘Spanish Ramparts,’ but I judge that they were thrown up against the Indians, in the time of De Nonville. A breast-work is still remaining.”—(Travels in America.) A similar work, circular or elliptical in outline, is said to exist in Lycoming county. Near it are extensive cemeteries.—(Day’s Hist. Coll., p. 455.)

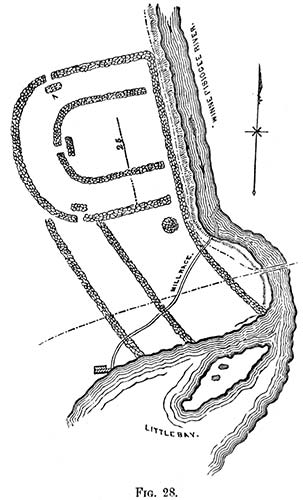

In the New England States few traces of works of this kind are to be found. There are, however, some remains in the State of New Hampshire, which, whatever their origin, are entitled to notice. The subjoined plan of one of these is from a sketch made in 1822 by Jacob ll. Moore, Esq., late Librarian of the Historical Society of New York, who has also furnished the accompanying description.

“According to your request, I send the enclosed sketch and memoranda of an ancient fortification, supposed to have been the work of the Penacook Indians, a once powerful tribe, whose chief seat was in the neighborhood of Concord, New Hampshire. The original name of the town was derived from that of the tribe. The last of the Penacooks long since disappeared, and with them have perished most of the memorials of their race. Enough has come down to us, however, in tradition, added to the brief notes of our historians, to show that the Penacooks were once a numerous, powerful, and warlike tribe. Gookin places them under the general division of the Pawtucketts, which he calls ‘the fifth great sachemship of Indians.’20 Under the name of Penacooks, were probably included all the Indians inhabiting the valley of the Merrimack, from the great falls at the Amoskeag to the Winnepiseogee Lake, and the great carrying place on the Pemigewasset. That they were one and the same tribe, is rendered probable from the exact similarity of relics, which have been found at different places, and from the general resemblance of the remains of ancient fortifications, which have been traced near the lower falls of the Winnepiseogee, in Franklin and Sanbornton, and on the table-land known as the Sugar-Ball Plain, in Concord. Tradition ascribes to each the purpose of defence against a common enemy, the Maquaas or Mohawks of the west.

“The accompanying sketch was taken in pencil, on a visit to the spot, in company with the Hon. James Clark and several friends in the month of September, 1822. The remains are on the west side of the Winnepiseogee, near the head of Little Bay, in Sanbornton, New Hampshire. The traces of the walls were at that time easily discerned, although most of the stones had been removed to the mill-dam near at hand, on the river. On approaching the site, we called upon a gentleman (James Gibson) who had lived for many years near the spot, and of whom we learnt the following particulars: He had lived in Sanbornton fifty-two years, and had known the fort some time previous to settling in the place. When he came to the town to reside, the walls were two or three feet high, though in some places they had fallen down, and the whole had evidently much diminished in height, since the first erection. They were about three feet in thickness, constructed of stones outwardly, and filled in with clay, shells, gravel, &c., from the bed of the river and shores of the bay. The stones of which the walls were constructed were of no great size, and such as men in a savage state would be supposed to use for such a purpose. They were placed together with much order and regularity, and when of their primitive height, the walls must have been very strong-at least, sufficiently strong for all the purposes of defence against an enemy to whom the use of fire-arms was unknown.

“The site of the fortification is nearly level, descending a little from the walls to the bank of the river. West, for the distance of nearly half a mile, the surface is quite even. In front or east, on the opposite side of the river, are high banks, upon which at that time stood a thick growth of wood. When the first settlers discovered the fort, there were oak trees of large size standing within the walls. Within the enclosure, and in the mound and vicinity, were found innumerable Indian ornaments, such as crystals cut into the rude shapes of diamonds, squares, pyramids, &c., with ornamental pipes of stone and clay,—coarse pottery ornamented with various figures,—arrow-heads, hatchets of stone, and other common implements of peace and war.

“The small island in the bay appears to have been a burial-place, from the great quantity of bones and other remains disclosed by the plough, when settlements were commenced by the whites. Before the island was cultivated, there were several large excavations, resembling cellars or walls discovered, for what purpose constructed or used, can of course only be conjectured. There is a tradition that the Penacooks, at the time of their destruction by the Maquaas, had three hundred birch canoes in Little Bay.

“After writing thus far, I addressed a note to the Hon. James Clark, of Franklin, New Hampshire, with inquiries as to the present state of these ruins. Mr. Clark was kind enough at once to make a special visit to the site of the ruins, in company with Mr. Bamford, son of one of the first settlers. The following is an extract from his reply:

“‘The remains of the walls are in part plainly to be traced; but the ground since our former examination has been several years ploughed and cultivated, so as to now give a very indistinct view of what they were at our previous visit, when the foundation of the whole could be distinctly traced. No mounds or passage-ways can now be traced. A canal to convey water to a saw and grist mill occupies the place of the mound marked m. The stones used in these walls were obtained on the ground, and were of such size as one man could lift; they were laid as well as our good walls for fences in the north, and very regular; they were about three feet in thickness and breast high when first discovered. The stones have been used, to fill in the dam now adjoining. There were no embankments in the interior. The distance between the outer and inner wall was about sixty feet; the distance from the north to the south wall was about 250 feet, and from the west wall to the river about 220 feet. There were two other walls extending south to Little Bay. The general elevation of the ground was about ten feet above, and gently sloping to the river bank, which is about five feet above the water of the river. The distance between Great Bay and Little Bay is about 160 rods, with a gradual fall of fifteen feet. Here was a great fishing-place for the Indians.’ Mr. Bamford states that he has heard his father and Mr. Gibson say, that on their first acquaintance with this place, they have seen three hundred bark canoes here at a time. This may have been in consequence of the number of bays and lakes near this place. Sanbornton was laid out and surveyed in 1750; but Canterbury, adjoining the bay, was settled as early as 1727.

“The remains of a fortification, apparently of similar construction to that above described, were some years since to be seen on the bluffs east of the Merrimack River, in Concord, on what was formerly known as Sugar-ball Plain. The walls could readily be traced for some distance, though crumbled nearly to the ground, and overgrown with large trees.”21

19. Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley.

20. Gookin, in l. Mass, Hist, Coll., I., 149,

21. “A mound 45 or 50 feet in diameter is situated on the northern shore of Ossipee Lake, New Hampshire. It is ten feet high, and was originally covered with timber. The earth is not like that of the meadow in which it stands, but of the adjacent plain. A slight excavation was made in it a number of years ago, in the course of which three entire skeletons were found, accompanied by two tomahawks and some coarse pottery. On the surrounding meadow were to be seen, when the ground was first cleared, the hills where the corn had anciently grown.”—Hist. and Mis. Coll. of N. H., Vol. II., p. 47: New Hampshire Gazetteer, p. 207.

http://scienceviews.com/squier/aboriginalmonumentsA-2.html

Aborignal Monuments

Lost American Antiquities: A Hidden History – Silencing the Ancient Mound Builders by Stephen E. Smoot

Chapter 10: Fortifications, Armor and Bone-heaps

E. G. Squier authored three books which would each give a different perspective into the daily lives of these ancient Mound Building cultures. In his 1848 book, Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, that he co-authored with the help of Dr. Davis, he would become famous, as it was the first publication of the Smithsonian. His second Book, Aboriginal Monuments of New York was a book that Squier had been hired by the Smithsonian to do separate from Davis. Then in 1851, Squier would publish, Antiquities of the State of New York, in which he included, A Supplement on the Antiquities of the West, printed in Buffalo, New York, by Geo H. Derby and Company, without the oversight and the aggressive editing of the Smithsonian. As a result, there is a good number of grammatical errors, as he gives more open, candid and revealing insights into the lives and decline of these ancient cultures.

Drawing on the wealth of knowledge he gained in his research over many years, Squier in his 1851 book gives expanded inferences into the lives of these ancient mound-building cultures. In writing on the strategic locations of these mounds and earthwork structures he states: “In respect of position, a very great uniformity is to be observed throughout. Most occupy high and commanding sites near the bluff edges of the broad terraces by which the country rises from the level of the lakes.”… “In nearly all cases they are placed in close proximity to some unfailing supply of water, near copious springs of running streams. Gateways, opening toward these, are always to be observed, and in some cases guarded passages are also visible.”67

Fortified Embankments

“Those works, which are incontestably defensive, usually occupy strong natural positions. …The natural strength of such positions, and their susceptibility of defenc[s]e would certainly suggest them as the citadels of a rude people, having hostile neighbors or pressed by foreign invaders. Accordingly, we are not surprised at often finding these heights occupied by strong and complicated works, the design of which is indicated no less by their position than by their heights occupied by strong and complicated works, the design of which is indicated no less by their position than by their peculiarities of construction.”68 Many of the fortifications as described by Mr. J. V. H. Clark “had been[e] inclosed with palisades of cedar.”69

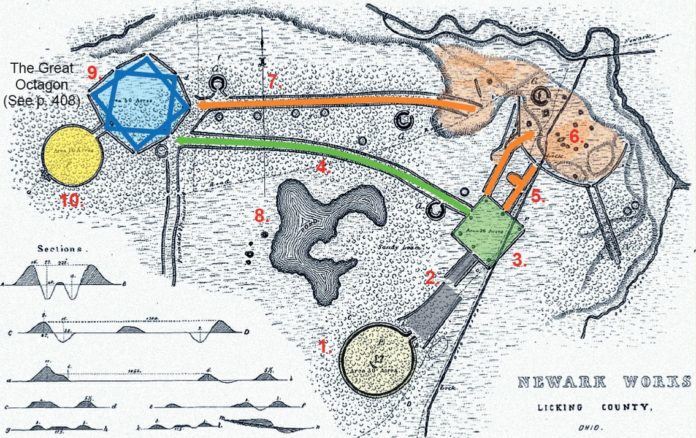

“Occasional works are found on the hill-tops, overlooking the valleys, or at a little distance from them; but these are manifestly, in most instances, works of defen[s]e or last resort, or in some way connected with warlike purposes. And it is worthy of remarks, that the sites selected for settlements, towns, and cities, by the invading Europeans, are often those which were the especial favorites of the mound-builders, and the seats of their heaviest populations. Marietta, Newark, Portsmouth, Chillicothe, Circleville, Cincinnati, in Ohio; Frankfort in Kentucky; and St. Louis in Missouri, may be mentioned in confirmation of the remark. The cent[er] of population are now where they were at the period when the mysterious race of the mounds flourished.”70

A.J. Conant gave an account of a Captain Carver in the Preface of his 1879 book, Foot Prints of Vanished Races in the Mississippi Valley, which he entered according to an act of Congress into the office of the Librarian of Congress in Washington. Speaking of Captain Carver he stated:

His testimony is selected from that of a multitude of early writers, because he could not have been prejudiced by the preconceived opinions or notions of others, and also because he was a man of military training, being a captain in the British army, whose conclusions would not be mere guess-work. The judgment of Brackenridge, Atwater, William Wirt and many distinguished men, is in perfect agreement upon this point, namely: that they [the mounds/cities] could not have been built by the Indians as we know them, nor any people (living) in a like condition.71

Captain Carver, in the account of his travels in the year 1766-78, describes what he was convinced was a military work, which he accidently discovered upon the bank of Lake Pepin. This was long before it was known that America had any antiquities. Concerning it he says that its form was somewhat circular, and its flanks reached the river. Though much defaced by time, every angle was distinguishable, and appeared as regular and fashioned with as much military skill as if planned by Vauban himself.’ Again: ‘I was able to draw certain conclusions of its great antiquity.’ “How a work of this kind could exist in a country that has hitherto (according to generally-received opinion) been the seat of war to untutored Indians alone, whose whole stock of military knowledge has only till within two centuries, amounted to drawing the bow and whose only breastwork, even at present, is the thicket I know not.72

O. Turner in his 1850 book, Pioneer History of the Holland Purchase of Western New York—Embracing Some Account of Ancient Remains, provides an analysis of the lack of knowledge of Native American communities and ancient civilizations. He believed that they were not responsible for the existence of the mound structures, forts, and other artifacts found in western New York. He would go on to say, of the Indians:

If their own history is obscure; if their relations of themselves after they have gone back but little more than a century beyond the period of the first European emigration, degenerates to fable and obscure tradition; they are but poor revelators of a still greater mystery. We are surrounded by evidences that a race preceded them, farther advanced in civilization and the arts, and far more numerous. Here and there upon the brows of our hills, at the head of our ravines, are their fortifications; their locations selected with skill, adapted to refuge, subsistence and defence [sic]. The uprooted trees of our forest, that are the growth of centuries, expose their mouldering [sic] remains; the uncovered mounds masses of their skeletons promiscuously heaped one upon the other, as if they were the gathered and hurriedly entombed of well contested fields. In our vallies [sic] upon our hill sides, the plough and the spade discover their rude implements, adapted to war, the chase, and domestic use. All these are dumb yet eloquent chronicles of by-gone ages.

We ask the red man to tell us from whence they came and whither they went? And he either amuses us with wild and extravagant traditionary legends, or acknowledges himself as ignorant as his interrogators. He and his progenitors have gazed upon these ancient relics for centuries, as we do now,—wondered and consulted their wise men, and yet he is unable to aid our inquires. We invoke the aid of revelation, turn over the pages of history, trace the origin and dispersion of the races of mankind from the earliest period of the world’s existence, and yet we gather only enough to form the basis of vague surmise and conjecture.

Turner then draws in the 1850’s these observations from their findings:

“I believe we may confidently pronounce that all the hypotheses which attribute those works to Europeans are incorrect and fanciful—first, on account of the present number of the works; secondly, on account of their antiquity; having from every appearance, been erected a long time before the discovery of America; and finally, their form and manner are totally variant from European fortifications, either in ancient or modern times.

It is equally clear that they were not the work of the Indians… It is apparent that Turner did not believe the American Indians were responsible, or connected with the ancient civilization that was responsible for the mounds. Would this culture of thinking deny the American Indians their rightful heritage?

What knowledge is left that might enable society to unlock the enigma of the Mound-Builders’ existence? Many of the giant earthworks, temple mounds, and effigy constructions show signs of a central government and of a spiritual and religious turning, built in times of peace and prosperity where ceremonies and religious rituals were shared. In their later constructions are found evidences of a time when the populations were motivated by fear, building hill-top fortifications and defenses. They incorporate ingenious military design and constructions and give signs of a time of ongoing conflicts, where the motivation behind these types of constructions was that of survival.

Angel Mounds, Indiana Palisade Fortification Covered with Clay Plaster

Places of Entrance Advancing and Receiving Armies

Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, 1848, Squier and Davis, Plate VI

Fortified Hill, Butler County, Ohio three miles below the town of Hamilton

Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, 1848, Squier and Davis, Plate VII Fort Ancient is located on the east bank of the Little Miami River

Fort Ancient, an account of this work was first published in a magazine entitled “Port Folio” in Philadelphia in 1809. In 1820 Mr. Atwater included it in his report to the American Antiquarian Society. It was also mapped and described by a Cincinnati Professor, John Locke in 1843.

E. J. Squier went on to write: “The vast amount of labor necessary to the erection of most of these works precludes the notion that they were hastily constructed to check a single or unexpected invasion. On the contrary, there seems to have existed a system of defenc[s]es, extending from the mouth of the Alleghany diagonally across the country, through Ohio to the Wabash. Within this range, those works which are regarded as defensive are large and most numerous.” 74

“It is clear that the contest was a protracted one, and that the race of the mounds were for a long period constantly exposed to attack. This conclusion finds its support in the fact that, in the vicinity of those localities, where, from the amount of remains, it appears the ancient population, was most dense, we almost invariably find one or more works of a defensive character, furnishing ready places of resort in times of danger.”75

Ancient Hopewell, Copper Celt

Among the implements recovered from the mounds, are several copper axes as shown in Fig. 81 and 82 of chapter XI, Implements of Metal, Squier and Davis, Ancient Monuments.

Fortifications

Artistic renditions. Top Left Ft. Carlise Germantown, Ohio , Top Right Pollock Earthworks Cedarville, OH Bottom left Ft Merom Indiana, Middle Right Interior Ft Hill Hillsboro, OH , Bottom Right, South Gate Ft. Ancient Lebanon, OH. Art by Wayne May.

Metalworking

“There is almost positive evidence that the mound-builders were an agricultural people, considerably advanced in the arts, and possessing great uniformity, throughout the whole territory which they occupied in manners, habits and religion—a uniformity sufficiently marked to identify them as a single people having a common origin, common modes of life and as a consequence, common sympathies, if not a common and consolidated government.”76 Squier’s gave this assessment in his third report, Antiquities of the State of New York, which, unlike the earlier reports, gives a greater insight into the human psychic, giving insight into their motivations and solemn ceremonies, and into their proficiencies in the shaping and hardening of metals. Of there proficiencies in metalworking, Squier said:

“They possessed the secret of hardening the metal […] so as to make it sub serve most of the uses to which iron is applied. Of it they made axes, chisels and knives. The mound-builders also worked it into similar implements, although it is not yet certain that they contrived to give any extraordinary hardness.”… “A specimen found in a mound near Chillicothe, Ohio consists of a solid, well-hammered piece of copper, and weighs two pounds and five ounces.” … “Silver has also been found, but in small quantities, reduced to great thinness and closely wrapped around copper ornaments. The ore of lead, galena, has been found in considerable abundance, and some of the metal itself under circumstances implying a knowledge of its use on the part of the ancient people. The discovery of gold has been vaguely announced, but is not well attested. It is not impossible that articles of that metal have been found.” 77

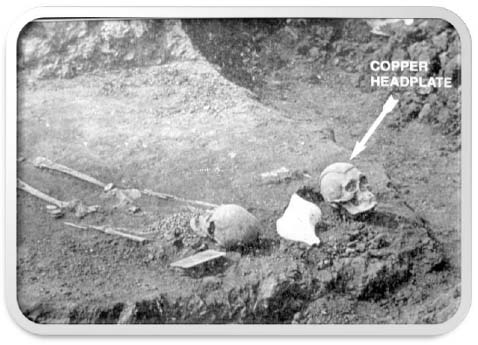

Metal Headplate “The Mound Builders” Henry Clyde Shetrone, 1930,

Fig. 61, p. 115 Copper plate with copper ear flaps and pearls attached.

Fig. 123. A HOPEWELL BURIAL ACCOMPANIED BY A TROPHY SKULL

“With the skeleton of a venerable male, accompanied by many implements

and ornaments, there was found the separate skull of a young male wearing a copper headplate. The latter probably was a trophy skull, either that of an enemy captured in battle or that of a relative retained as a family relic,” p. 199.

“It has already been remarked that the mounds are the principal depositories of ancient art, and that in them we must seek for the only authentic remains of the builders. In the observance of a practice almost universal among barbarous or semi-civilized actions, the mound-builders deposited various articles of use and ornaments with their dead. They also, under the prescriptions of their religion, or in accordance with customs unknown to us, and to which perhaps no direct analogy is afforded by those of any other people, placed upon their alters numerous ornaments and implements– which remain there to this day, attesting at once the religious zeal of the depositors and their skill in the minor arts.” 78

“In one case which fell under my observation, and in another which I have an account from the person who discovered it, the altar was of stone. … It was a simple elevation of earth packed hard, and was faced, on every side and on top, with slabs of stone of regular form, and nearly uniform thickness. They were laid evenly, and as a mason would say, ‘with close joints.’…This altar bore the marks of fire, and fragments of the mound-builders’ ornaments were found on and around it.”

“The Mounds of this class are most fruitful in relics of builders. On the altars have been found, though much injured and broken up by action of fire, instruments and ornaments of silver, copper, stone and bone; beads of silver, copper, pearls, and shells, galena, sculptures of the human head, and of numerous animals; pottery of various kinds, and a large number of interesting articles, some of which evi[de]nce great skill in art.” 79

Bone Heaps

In the History of the Holland Purchase (1849), in a location a mile north of Aurora Village, New York, there are several small lakes and ponds, around and between which are knobs of elevations, thickly covered with a tall growth of pine; upon them are several mounds where many human bones have been excavated. There are in the village and vicinity, gardens and fields where relics are found at each successive plowing. Few cellars are excavated without discovering them. In digging a cellar upon the farm of P. Pierson, a skeleton was exhumed, the thighbones of which would indicate great height; exceeding by several inches, that of the tallest of our own race. 80

“The mounds which formerly existed in Erie, Genesee, Monroe, Livingston, St. Lawrence, Oswego, Chenango, and Delaware counties, all appear to have contained human bones, in greater or less quantities, deposited promiscuously, and embracing the Skeletons of individuals of all ages and both sexes. They, probably, all owe their origin to a practice common to many of the North American tribes, of collecting together, at fixed intervals, the bones of their dead, and finally depositing them with many and solemn ceremonies. They were some times heaped together so to constitute mounds.”81

The “bone pits” which occur in some parts of Western New York, Canada and Michigan, etc., have unquestionably a corresponding origin…. They are of various sizes, but usually contain a large number of skeletons. In a few instances the bones appear to have been arranged with some degree of regularity. One of these pits discovered some years ago, in the town of Cambia, Niagara County, was estimated to contain the bones of several thousand individuals. …This locality was visited and examined by Mr. O. Turner, of Buffalo, in 1823. The account of this gentleman is published in his history of the “Holland purchase,” page 27 as follows: “The location commands a view of Lake Ontario and the surrounding country. An area of six acres of level land seems to have been occupied; fronting which, upon the circular verge of the mountain, were the distinct remains of a wall. Nearly in the centre of the area was a depository of the dead. It was a pit excavated to a depth of four or five feet, filled with human bones, over which were piles of sandstone. Hundreds seem to have been thrown in promiscuously, of both sexes and all ages. Numerous barbs or arrow-points were found among the bones and in the vicinity. It has been conjectured that this had been the scene of some sanguinary battle, and that these are the bones of the slain.”82

PUBLISHER Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum

Another which I [Squier] visited in the town of Clarence, Erie County, contained not less than four hundred skeletons. A deposit of bones comprising a large number of skeletons was found, not long since, in making some excavations in the town of Black Rock, situated on Niagara River, in Erie county…In Canada similar deposits are frequent. Accounts of their discovery and character appeared in various English publications, among which may be named the “British Colonial Newspaper” of September 1847, and the “Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal,” for July 1848. From a communication in the latter by Edward W. Bawtree, M.D., the subjoined interesting facts are derived. “A quantity of human bones was found in one spot in 1846 near Barrie, and also a pit containing human bones near St. Vincent’s. Great numbers were found in the latter, with several copper and brass kettles, and various trinkets and ornaments in common use among the Indians.”83

“The large cemeteries which have been discovered in Tennessee, Kentucky, Missouri and Ohio, seem to have resulted from a similar practice.”84 The practice of mounding dirt over their dead or in burying their dead in mounds above the natural terrain of the land, has all served to give evidence of their existence. We now understand that there were large populations found in North America anciently, as evidenced by their ruins, giant earth works structures, artifacts and fortifications. Their bone pits and the abundance of their abandoned ancient ruins also give signs of their rapid demise. As history has shown, most massive and rapid declines in populations are usually associated with the introduction of disease to a culture or the result of devastating wars.

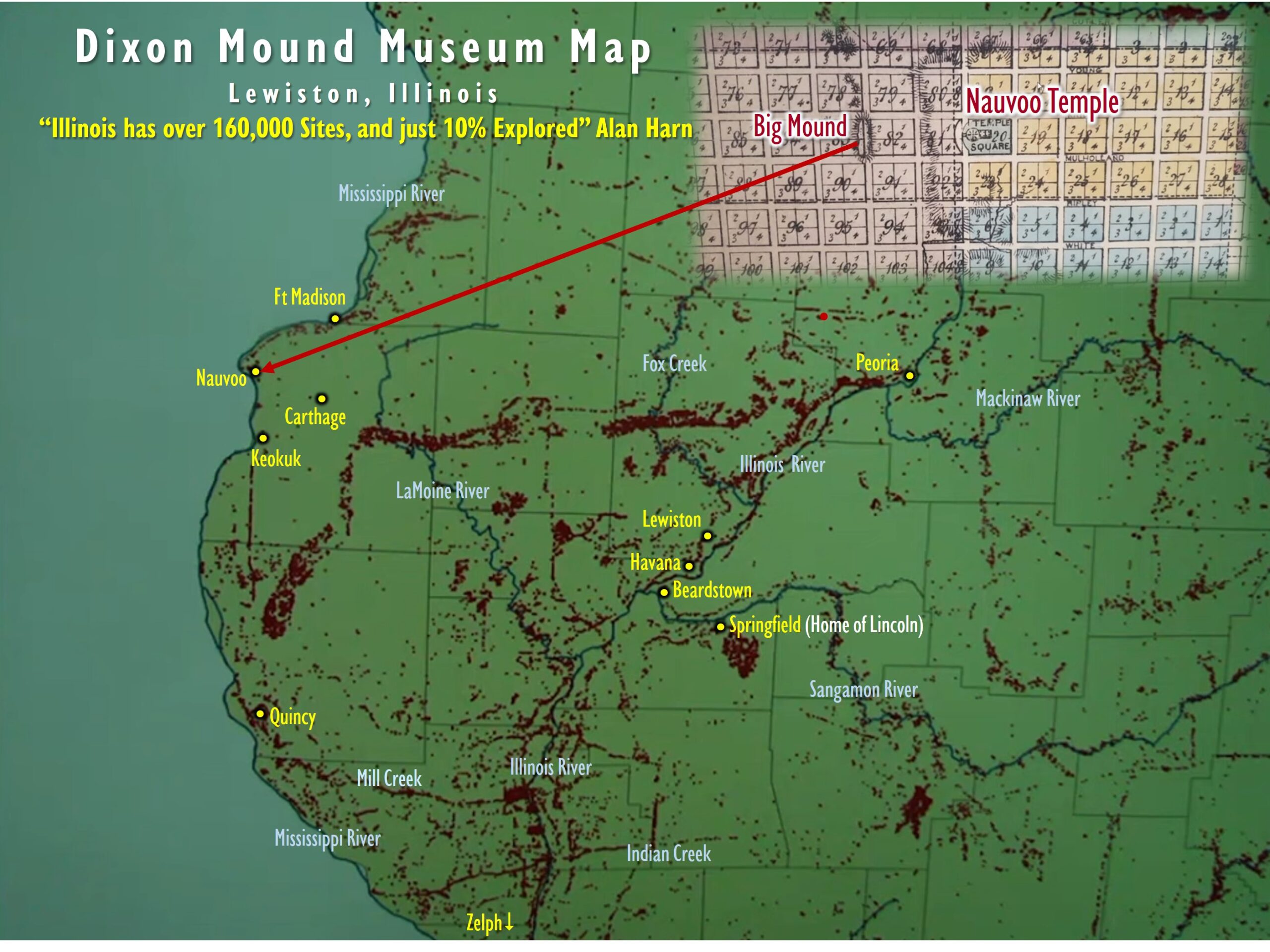

Dickson Mound Excavation

_______________________

67 E. G. Squier: Antiquities of the State of New York: Buffalo, Geo. H. Derby and Co. 1851, 12

68 Ibid. 300, 301

69 Ibid. 38

70 Ibid. 208

71 A. J. Conant, A.M., Foot Prints of the Vanished Races of the Mississippi Valley, (St. Louis: Chancy R. Barns, 1879; reprinted Colfax, WI: Hayriver Press, 2007) Preface, iv, v.

72 Ibid.

73 O. Turner, Pioneer History of the Holland Purchas of Western New York, Jewett, Thomas & Co., Buffalo, N.Y., 1850, 18-22.

74 E. G. Squier: Antiquities of the State of New York: (1851), 303

75 Ibid. 304

76 Ibid. 304

77 Ibid. 328

78 Ibid. 326

79 Ibid. 317, 318

80 See; Fritz Zimmerman; The Nephilim Chronicles, Fallen Angels in the Ohio Valley: 80,81

81 E. G. Squier: Antiquities of the State of New York: (1851), 98

82 Ibid. 99, 100 and included references

83 Ibid. 100

84 Ibid. 99