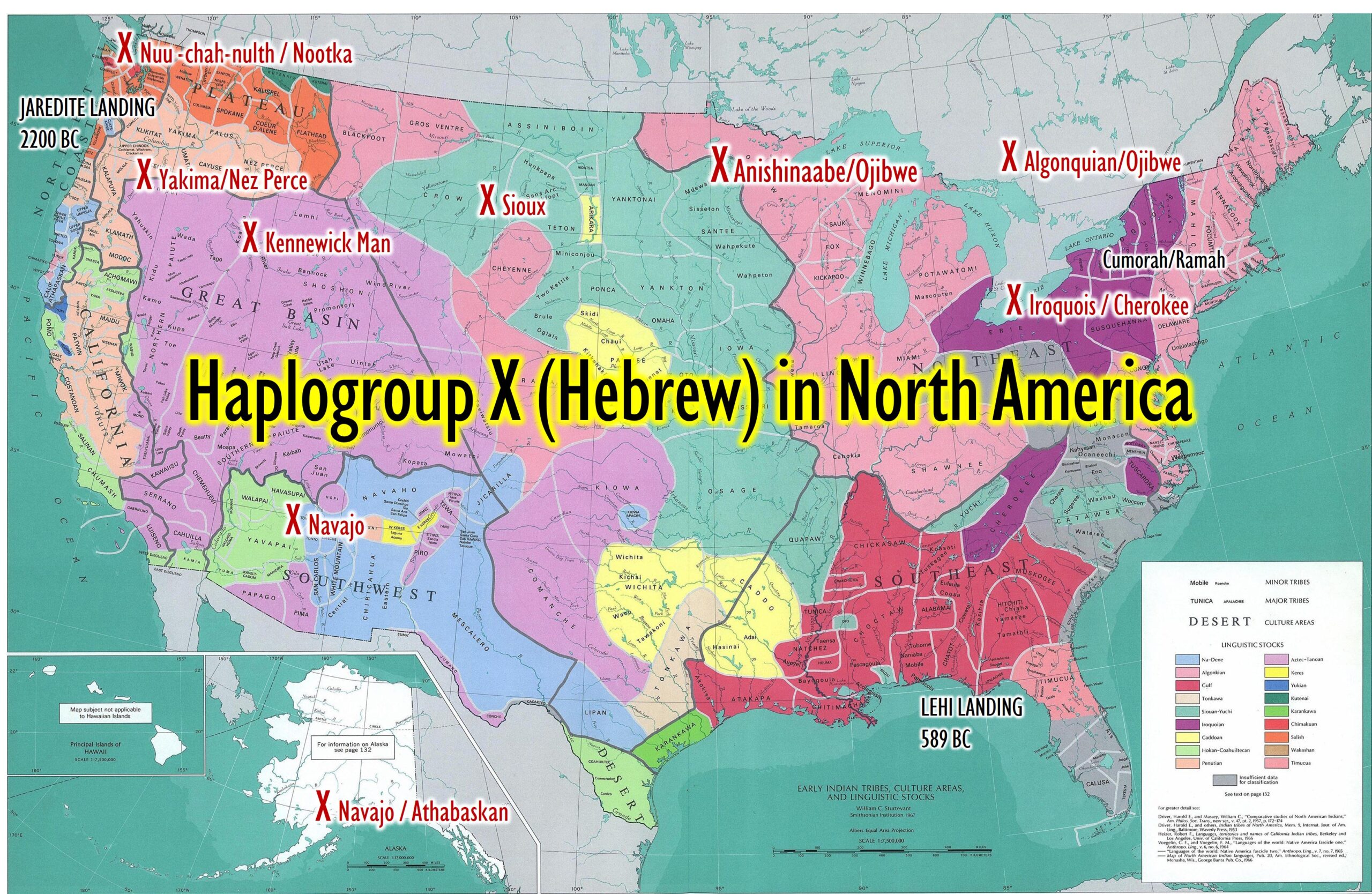

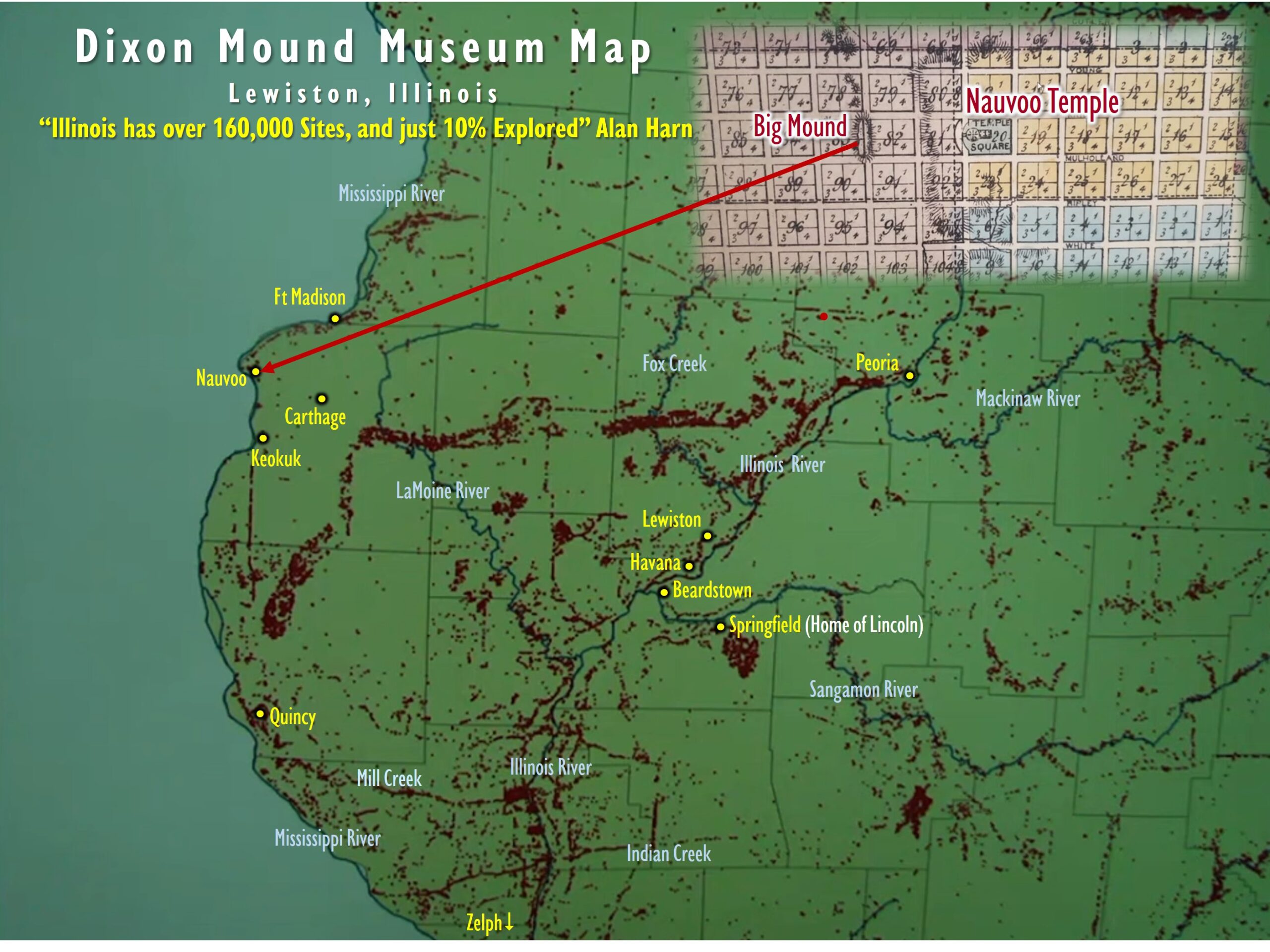

Once again I am amazed at all of the significant archaeology that has been found, that shows a Nephite or Jaredite timeline all over North America. How can anyone miss all of this information coming from the ground as was prophesized. I believe the biggest challenge in the past, has been that historians and Intellectuals were looking in Mesoamerica and not in the USA.

How Can a Person be so Wrong?

Latter-day Saint Thomas Stuart Ferguson was the founder of BYU’s archaeology division (New World Archaeological Foundation). NWAF was financed by the LDS Church. NWAF and Ferguson were tasked by BYU and the Church in the 1950s and 1960s to find archaeological evidence to support the Book of Mormon. After 17 years of diligent effort, this is what Ferguson wrote in a February 20, 1976 letter about trying to dig up evidence for the Book of Mormon: “…you can’t set Book of Mormon geography down anywhere – because it is fictional and will never meet the requirements of the dirt-archaeology. I should say — what is in the ground will never conform to what is in the book.” https://www.bookofmormoncentralamerica.com/2021/09/fair-lds-again-and-skousen-on-witnesses.html

If you live into the next century you will see evidence for the Book of Mormon come forth in droves.” Truman G. Madsen, speaking of what the Prophet Joseph Smith said to a colleague, in the opening statement of the 2005 video, “Journey of Faith.”

Elder Jeffery Holland said, “In one of the earliest such manifestations after His Resurrection, Jesus came to the eleven, inviting them to touch His hands and feet as He sat to eat meat and honeycomb. To those who doubted, Mark says He upbraided them with their unbelief and hardness of heart. The message is that if members of the Godhead go to the trouble of providing many infallible proofs of truth, then surely we are honor bound to affirm and declare that truth and may be upbraided if we do not. My testimony to you tonight is that the gospel is infallibly true and that a variety of infallible proofs supporting that assertion will continue to come until Jesus descends as the ultimate infallible truth of all. Our testimonies aren’t dependent on evidence; we still need that spiritual confirmation in the heart of which we have spoken but not to seek for and not to acknowledge intellectual, documentable support for our belief when it is available is to needlessly limit an otherwise incomparably strong theological position and deny us a unique, persuasive vocabulary in the latter-day arena of religious investigation and sectarian debate. Thus armed with so much evidence of the kind we have celebrated here tonight, we ought to be more assertive than we sometimes are in defending our testimony of truth.

To that point I mention that while we were living and serving in England, I became fond of the writing of the English cleric Austin Farrer. Speaking of the contribution made by C. S. Lewis specifically and of Christian apologists generally, Farrer said: Though argument does not create conviction, lack of it destroys belief. What seems to be proved may not be embraced; but what no one shows the ability to defend is quickly abandoned. Rational argument does not create belief, but it maintains a climate in which belief may flourish.

May we leave to Nephi, son of Helaman, the last word regarding our celebration of gospel scholarship tonight. Said he of that which God has given an infallible proof:

“And now, . . . ye know these things and cannot deny them [because of the] many evidences which ye have received; yea, even ye have received all things, both things in heaven, and all things which are in the earth, as a witness that they are true.” Heleman 8:24

When such revelation comes, when that complete witness is borne to our heart and our head, then surely we will know how Martin Harris felt when, after considerable struggle of both body and spirit, he was able to behold the angel Moroni holding the gold plates, turning their leaves one by one before his very eyes. In response to that spiritual and temporal evidence he shouted for all of us, “Tis enough, ‘tis enough; mine eyes have beheld, mine eyes have beheld.” Joseph Smith, History, 1838-1856, vol. A-1, 25, Church History Library

May our Father in Heaven bless us and an ever-larger cadre of young scholars around the Church to do more and more to discover and delineate and declare the reasons for the hope that is in us, that like those converted Lamanites, we may with bold conviction hold up to a world that desperately needs it “the greatness of the evidences which [we have] received,” Heleman 5:50, especially of the truthfulness of the Book of Mormon, the keystone of our religion. In the name of Jesus Christ, amen.” The Greatness of the Evidence By Elder Jeffrey R. Holland, August 16, 2017

Elder Holland speaks above about the importance that, “if members of the Godhead go to the trouble of providing many infallible proofs of truth, then surely we are honor bound to affirm and declare that truth.” [Could infallible truths be found in artifacts and archaeological findings? I say yes.] Then Elder Holland continues to say we should “acknowledge intellectual, documentable support for our belief” [I have found many of the archaeological findings to be intellectual and documentable in my search for truth], and as I add the power of prayer and the spirit, I have received many personal revelations for the truth of the Book of Mormon found in the ground all over North America. Let’s now discover some of that infallible truth in the mounds all around Cleveland and Kirtland, Ohio.

Indian Point Cleveland, OH

“Indian Point, located just 14 miles northeast of the Kirtland Temple. This ancient Indian enclosure features two earthen walls bordered by ditches and protected on two sides of a triangle by steep cliffs. The walls were built around 140 B.C.” Jonathan Neville by reading the signage at the site.

“The most spectacular Cleveland area earthworks are surprisingly little known to many area residents. The prehistoric embankments are still sufficiently high as to be easily viewed. The site is Indian Point (33La2) located at the juncture of the Grand River and Paine Creek just east of Painesville, Ohio. The site is now part of the Lake Metro-park system. The archaeological community, who has been interested in the area long before it became a park, calls it the Lyman Site because it is on the former grounds of a military training camp operated by Charles Lyman. The site consists of three earthen enclosures atop a steep river bluff. (The western set of walls is severely eroded but the eastern two are easily viewed.) Indian Point did not have mounds; mound-like structures found there have more recently been determined not to be of prehistoric human origin. Until recently the Early Woodland date of Indian Point was not recognized; it was considered strictly a Late Prehistoric site (900 AD-1650 AD) because of the large amount of ceramics and bone tools of this period found there. Archaeologist James Murphy has long obtained radiocarbon dates prior to the First Millennium AD. He tested remains of cooking fires from deep within the inner earthworks. He also found an Early Woodland Stemmed point. The dates of specific portions of the site including the earthen walls still remain a matter of controversy. Murphy has proposed that the two sets of earthworks may have been constructed at different times.” 2011 LAURA PESKIN Prehistoric Indian Earthworks in the City of Cleveland and Environs

Once again this is a long blog about the Ohio area of the United States as the heart of the Heartland of the Nephites. I believe Ohio is their land and the Hebrew artifacts show amazing evidence. The mounds in just the area around Cleveland are immense and that is mainly what this blog is about. The sacred place of Kirtland, Ohio could very well be the land where the Savior visited the Nephites after His resurrection. Read and enjoy!

OHIO Mound Parallels with the NEPHITES

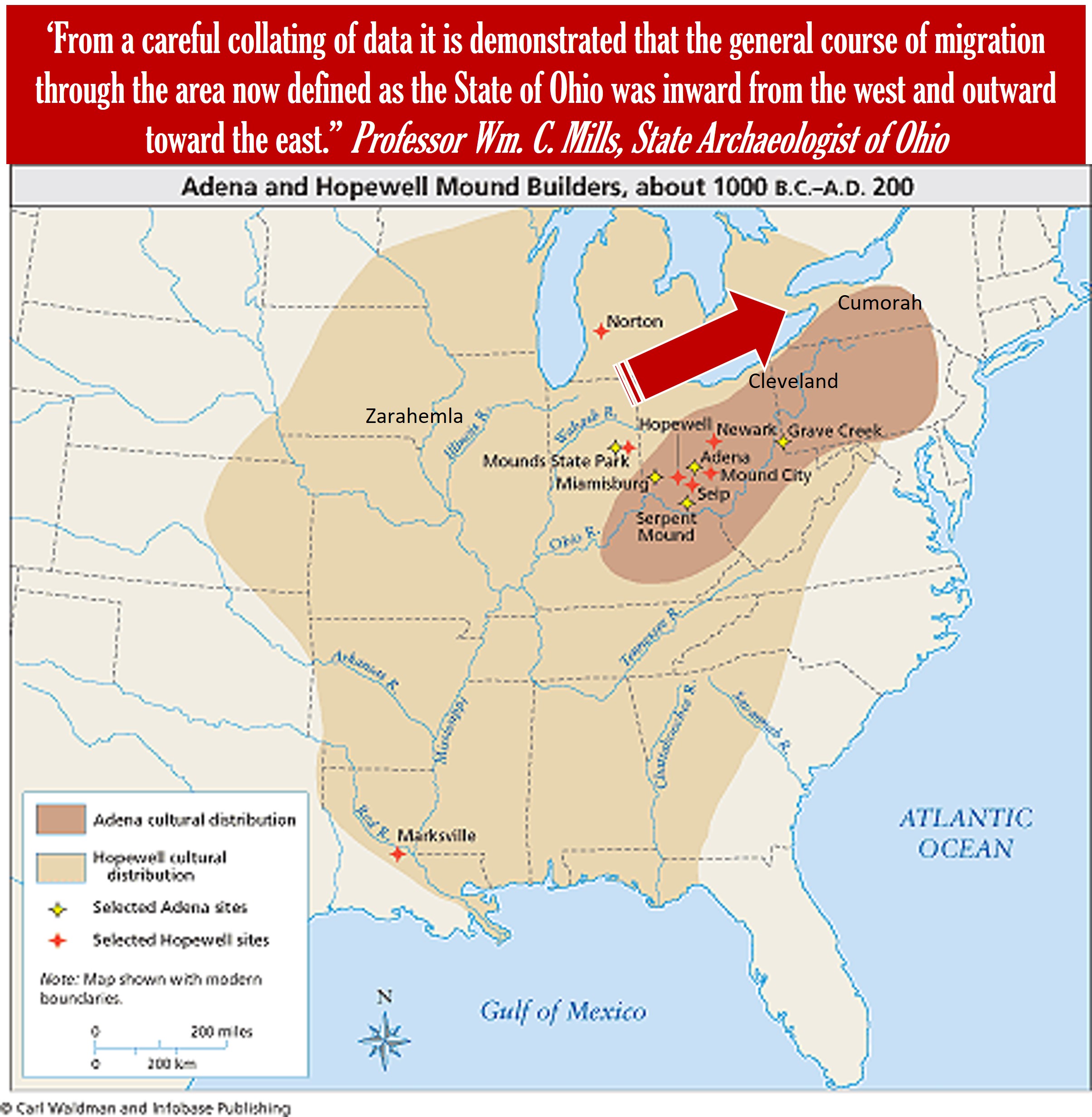

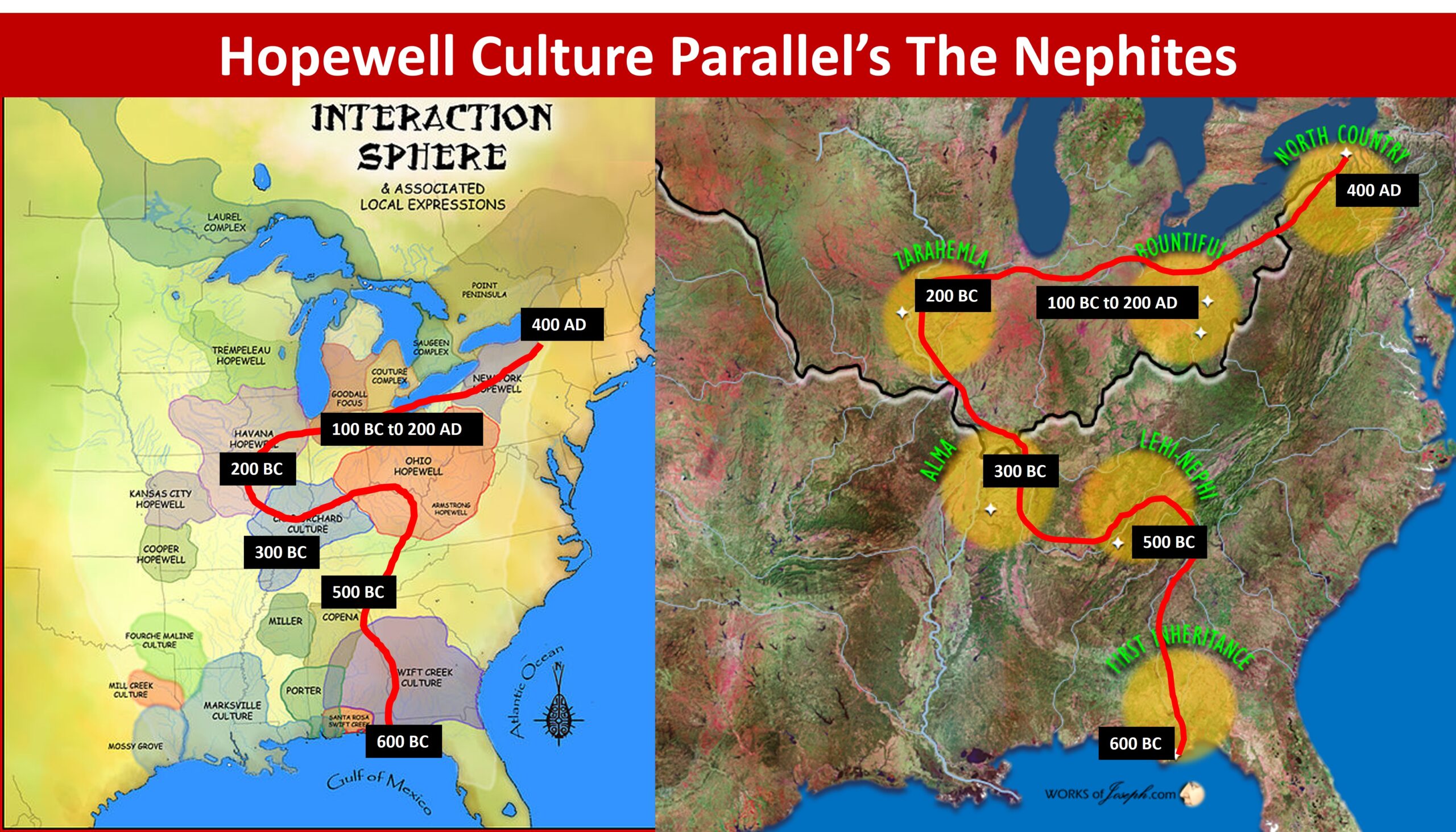

Parallels of the Hopewell Culture as described by William C. Mills, Chief Archaeologist of Ohio, with the Book of Mormon“[May 20, 1917; Sunday] Attended Sunday School and afternoon service in Hawthorne Hall, and was a speaker at each assembly. Evening meetings here, as also in Brooklyn, have been discontinued for the summer. The attendance both at Sunday School and afternoon meeting was surprisingly large in view of the fact that many of the Utah college students have left for the vacation period. This evening at the hotel I had a long and profitable consultation with Professor Wm. C. Mills, State Archaeologist of Ohio. He is continuing his splendid work of exploration in the Ohio mounds, and I went over with him again the remarkable agreement between his deductions and the Book of Mormon story. He has reached the following (10) conclusions: The area now included within the political boundaries defining the State of Ohio was once inhabited by two distinct peoples, representing two cultures, a higher and a lower. These two classes were contemporaries; in other words, the higher and the lower culture represented distinct phases of development existing at one time and in contiguous sections, and furnish in no sense an instance of evolution by which the lower culture was developed into the higher. These two cultural types or distinct peoples were generally in a state of hostility one toward the other, the lower culture being more commonly the aggressor and the higher the defender. During limited periods, however, the two types, classes, or cultures, lived in a state of neutrality, amounting in fact to friendly intercourse. The numerous exhumations of human bones demonstrate that the people of the lower type, if not indeed both cultures, were very generally affected by syphilis, indicating a prevalent condition of lasciviousness. Their (are) two peoples or cultures…the lower culture was most commonly the assailing party, while the people of the higher type defended as best they could but in general fled. As a further consequence of this belligerent status they buried their dead, with or without previous cremation, in such condition as to admit of expeditious covering up of the cemeteries by the heaping of earth over the sepulchers [sic], in which hurried work the least skilled laborers and even children could be employed. From a careful collating of data it is demonstrated that the general course of migration through the area now defined as the State of Ohio was inward from the west and outward toward the east. Professor Mills states that no definite data as to the age of these peoples have as yet been found, but that the mounds may date back a few hundred years or even fifteen hundred or more. Several years ago I placed a Book of Mormon in the hands of Professor Mills and, while he is reticent as to the parallelism of his discoveries and the Book of Mormon account, he is impressed by the agreement.” James E. Talmage 20 May 1917

See my detailed blog about Ohio here!

Jews are Lamanites

“I would say to the Lamanites, if I could speak to them understandingly, that you are also a branch of the house of Israel, and chiefly of the house of Joseph, and your forefathers have fallen through the same examples of unbelief and sins, as have the Jews, and you, as their posterity, have wandered in sin and darkness for many generations; and you, like the Jews, have been driven and trampled under the foot of the Gentiles, and put to death through your wars with each other, and with the white man, until you are almost destroyed. But there is still a redemption and salvation for a remnant of you in the latter days.” History of His Life and Labors By Wilford Woodruff

A Survey of Prehistoric People in the Cuyahoga Lands

In this essay the term Greater Cleveland means Cuyahoga County and all areas from its heart to its periphery. The Cuyahoga River divides the city and county roughly down the middle. Its terminus at Lake Erie, its floodplains and its high bluffs have always enticed Native peoples as well as later Europeans. The Cuyahoga River Valley refers to the deep gorge system cut by the river south of downtown Cleveland and extending all the way to the glacial escarpment in the northern part of the city of Akron. Here the river makes its “Big Bend” to the east and ultimately to its source 30 miles to the northeast in Hambden Township, Geauga County, Ohio.

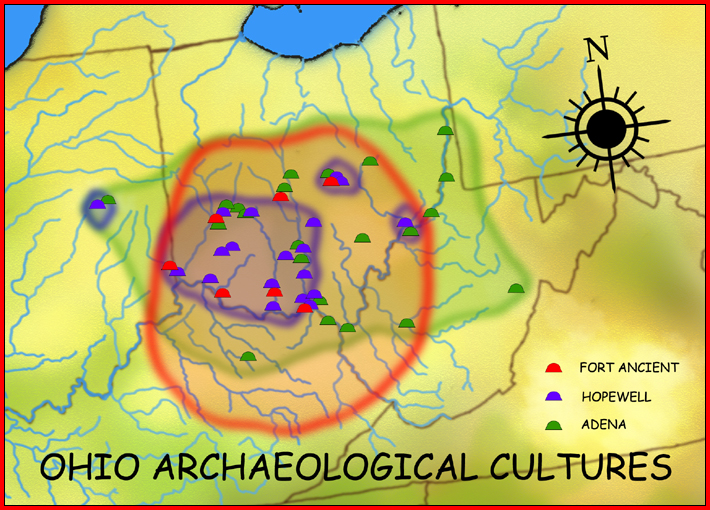

The Cleveland region has rich prehistory that goes back over 11,000 years. On a less grand scale than the spectacular ruins in Southern Ohio, remains of Adena and Hopewell ceremonialism and mortuary ritual are common in Northeast Ohio. There are also relics present of the Mississippian culture which flourished to a greater extent in Southern Ohio in the Late Prehistoric Period (900 to 1650 AD).

The geology of the Cuyahoga lands, right where the Allegheny Plateau, Central Till Plains and Great Lakes Plain meet, could have been significant for the proliferation of human activity in this region in all eras. The eroding Allegheny escarpment has provided ready Paleozoic building material in the form of the Euclid Bluestone, Berea Sandstone, and Cleveland Siltstone. Another geological feature that shaped human activity in the region is its position directly southeast of a large lake (Erie). Thus storms from the Northwest have battered the region since time immemorial, leaving precipitation that has carved its way into swift moving streams teeming with fish. Unbeknownst to many Northeast Ohioans today, the region is also strategically located on a continental divide; waters north of the so-called Great Bend in northern Akron flow ultimately into Lake Erie; those eight miles to the south (today Lake Nesmith in Coventry Township), flow into the Tuscarawas River and ultimately into the Gulf of Mexico. As this book will point out, the continental divide provided transportation advantages in this region from ancient times all the way up to the advent of railroads in the mid-19th Century.

The region south of Lake Erie was important in the Archaic period (7,000 to 1,000 BC). There have been more revealing Archaic findings in Northeast Ohio than interesting artifacts from later prehistoric Indians. Key Archaic developments in the region that is now Northeastern Ohio were commencement of atlatl or spear thrower use 5., and greater dependence on both wild plants and fish in the diet.

Northeast Ohio’s prehistoric peoples distinguished themselves in the following millennium (Early, Middle Woodland periods) by commencing the region’s first agriculture. More important in Ohio prehistory are their followers, the Late Woodland people of 500 to 900 AD. Northeastern Ohio holds a large percentage of the state’s significant Late Woodland archaeology. The Late Woodland period saw transitions to localism and improved food procurement, storage and preparation.

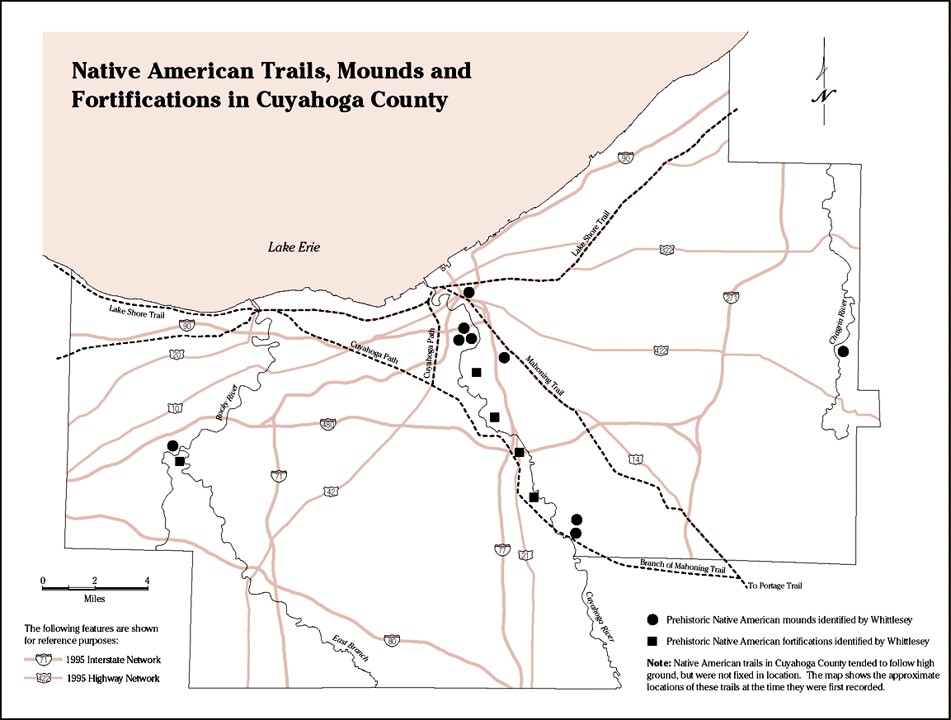

As recently as 1650 there was a distinct population of prehistoric Native Americans roughly between Conneaut, Ohio on the east and the Black River on the west. This people are referred to as Whittlesey Culture after Col. Charles Whittlesey, civic leader, archaeologist and first president of the Western Reserve Historical Society. He was the first person to describe and map much prehistoric Indian activity in Northeast Ohio. No-one knows exactly why the archaeological record indicates an abrupt cessation of Whittlesey culture. (Some theories of its demise will be discussed at the close of this article). Changes in pottery style and a transition to a more sedentary lifestyle characterized Whittlesey culture. Other features included reliance on local resources rather than trade goods. Mortuary ritual appears simple from the lack of mounds and grave goods found. Some Mississippian influences took hold.

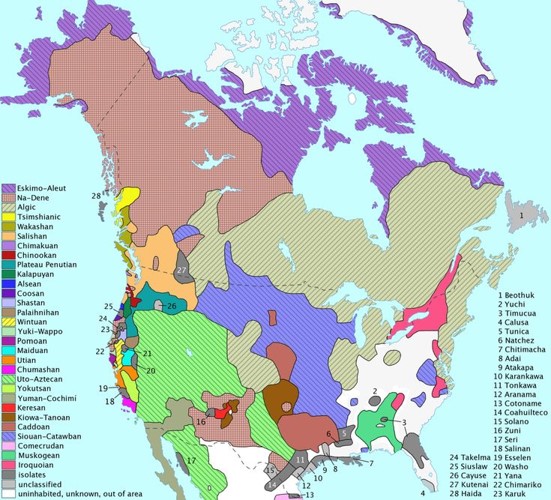

Until around 1650 northeast Ohio entirely belonged to the native peoples who had long inhabited it. The lucrative Colonial-era fur trade and the 1539 formation of the Iroquois Confederacy brought outsiders into the region, if largely of Native American blood themselves. The great Iroquois Confederacy, one of the foremost historic powers on the North American continent, until 1726 controlled the lands around the Cuyahoga River which the Iroquois used for hunting. Lake Erie in its entirety was so remote that Champlain’s 1634 map of New France properly named and drew the other three Great Lakes within its province; Erie the map distorted and failed to name.

In 1726 the Iroquois made a treaty which ceded their southeastern Lake Erie holdings to the British. The French vied for control, and obtained it, although for all intents and purposes they shared their dominion over Lake Erie with the Indians. A 1690 treaty between the French and the Iroquois, previously enemies, had allowed the French to establish posts on the lake. The first Europeans to familiarize themselves with the Cuyahoga lands were anonymous French missionaries who described the area to 1650 map-maker Nicholas Sanson. The first European resident on the Cuyahoga was French fur trader Francois Saguin who established a post in 1742. It was in the Cuyahoga Valley though on which side of the river is uncertain.

The first Briton to show familiarity with the Cuyahoga lands was Christopher Gist, surveyor for Virginia’s Ohio Company. The first British resident on the Cuyahoga was Col. George Croghan. He traded with area Indians in the 1740s as well as establishing other trading posts in the Ohio country. His friendliness with the Cuyahoga Valley Indians led many of them to favor the Briitsh. During most of the years between 1744-1760 the French and British fought over disputed portions of present-day Ohio and neighboring states in the Western Hemisphere correlates of King George’s War and the Seven Years’ War, both between Britain and France. In the United States the latter war is referred to as the French and Indian War. After these wars ended, a new alliance continued to make the area dangerous for the British, save a few missionaries and traders; in the 1760s great Ottawa chief Pontiac formalized a land-holding organization of the so-called Northwest Indian nations: the Ottawa, Chippewa, Wyandot and Delaware.

The Ottawas, a nation originating north of the Great Lakes, gradually migrated into the sparsely populated and loosely held southern Erie shores, reaching the vicinity of the Cuyahoga River in the Mid-18th Century. An area of settlement lasting about 50 years from around 1760 to about 1810 was near both the river and what is now Columbia Road in Boston Township, Summit County. During the latter years the site grew into a village under the locally well known Chief Ponty (not to be confused withe the great Ottawa Chief Pontiac.) Their confederates the Chippewa, closely related in language, gravitated to what’s now Brecksville after they settled into the Cuyahoga Valley. A French official also reported Chippewa living at “Mingo Town” in the mid-1840s. Though the word “Mingo” referred to Iroquois, both Iroquois and non-Iroquois lived in this large village. Mingo Town was in the general Cuyahoga Valley area, but archaeology has still not pinpointed the location with certainty. Nonetheless at its height, it was home to as many as 2,000 Indian individuals as estimated from the reports of the French official, Robert Navarre.

The Ottawas became better acquainted with another of their fellow Algonquian speakers, the Delaware, as both defended Fort Duquesne in the French and Indian War. Pontiac and other Ottawa may have already known the Delaware from the Ohio country; The Delaware, dispossessed of their homelands further east, had settled along the Cuyahoga River, both in the River Valley and around the strategic Great Bend region. John Hecklewelder, missionary and explorer to Northeast Ohio, recalled Delaware visionary leader Neolin in the Mid-18th Century living at a time on the Cuyahoga fairly close to Lake Erie, and then also for a time on the Tuscarawas River, at the southern end of the great canoe portage 1.

Few Whites were to be found in the Cuyahoga lands from the end of the French and Indian War to the end of the American Revolution. Afterwards from 1785 to 1795 treaties between the new American government and Ohio country Indians left the area east of the Cuyahoga River to the White Man. In 1796 Moses Cleaveland with a party of several men landed on the mouth of the Cuyahoga River to survey the area for the Connecticut Land Company. The land investments in Northeast Ohio were on territory called Connecticut’s Western Reserve. Connecticut had claimed the Reserve and then sold it part of it to private speculators. Connecticut retained ownership of the western portion of the Reserve called the Firelands. As its name implied, Connecticut gave this land away to its citizens whose homes had burned in the American Revolution. The city of Cleveland which sprouted on the mouth of the Cuyahoga River is of course named after Moses Cleaveland.

The Greenville Treaty of 1795 prohibited Indian settlement east of the Cuyahoga River. The Indians who continued to frequent the East Side mainly were hunters and fisherman who set up camp. Indians land claims were permitted on the West Side of Cleveland until the signing of another treaty in 1805. They stayed on afterward too due to the low land pressure; Cleveland in its first 25 years had less than 150 White settlers. It took the beginning of a canal system a few years later to finally bring immigrants into Cleveland. 1825 marked the opening of the Erie Canal to the east. The Ohio and Erie Canal, completed in 1832, connected Cleveland and Lake Erie with the Virginia settlements in southern Ohio.

Relics Remembered by Cleveland’s Early Settlers

The first mounds mentioned in this study as follows were unknown to all but Cleveland’s earliest settlers. Some ambiguity surrounds the authenticity of these relics. Their descriptions relied on the fading memories of Cleveland’s founders when they realized many years later that details of the city’s early history might be something worth committing to writing. Also the tendency for the human mind to think events occurred longer ago than actuality is operative here. Finally since these mounds of memory have never been examined for artifacts, it is possible that they were naturally occurring features and not constructed by human inhabitants. This is not to say that there was not human activity in the Late Prehistoric or Woodland periods in what is now downtown Cleveland. The area’s location at the mouth of a major river suggests that the area probably attracted humans in all eras. For example artifacts found in the vicinity of East Ninth Street, some mentioned in this study, support the existence of prehistoric inhabitants in what is Cleveland’s downtown area.

An Indian mound at the mouth of the Cuyahoga

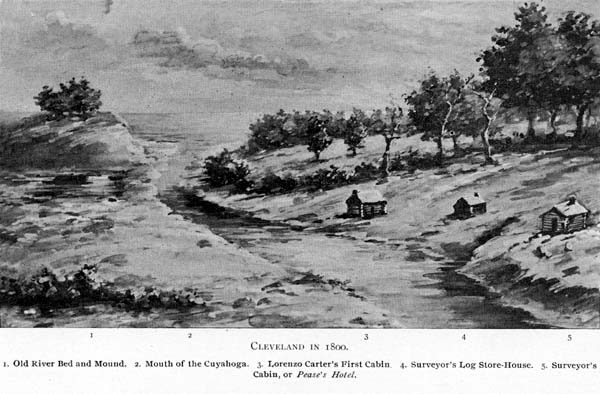

A mound at the mouth of the Cuyahoga River was quite sizable, perhaps up to 150 feet in diameter and 75 feet tall. It was gradually lost after Clevelanders rechanneled the mouth of the Cuyahoga River too close to it. The rechanneling occurred in the 1820s as an infrastructure improvement for the simultaneous building of the Erie Canal. Before the rechanneling the mound was in fact not at the mouth of the river as pictured below; the mouth was around a mile to the west, at the terminus of what is known as the Old Riverbed. The painting below, created for Cleveland’s 1896 Centennial, depicts the rechanneled river directly east of the mound. The painting is based on an 1820s woodcut of the same scene. The woodcut in turn is based on a drawing by Captain Allen Gaylord.

There was at least one other Indian mound near what is now Cleveland’s Public Square. It stood on what became Ontario Street, just south of Prospect Avenue. This point in our present-day is just east of Tower City Center and just west of Myers University. Isham Morgan, an original area settler, had a good view of the mound around 1812 when he rode on horseback to Cleveland with his father.

Morgan observed over a period of “several” years that the mound became leveled. He noted that in 1812 Ontario Street was in a forested region which stretched east, south and west. Ontario Street only ran south of Public Square and even there, it was merely a path through woods. (Newburgh Township, four miles to the southwest, where Morgan then resided, was more developed; Cleveland in a comparative context was a clearing in the woods.) Thus in the early days of Cleveland not much disturbance came to the mound. As Cleveland transitioned from a little New England Village to an industrial center, the mound gave way to urban settlement. Its location is in the heart of the city’s commercial activity.

The Garlick and Gaylord Mounds to be discussed shortly were also in the downtown area of Cleveland. Then come a small cluster of mounds around East 55th Streets that perhaps followed the course of the Cuyahoga River south-eastward. These include the Mound Avenue site and the following two sites on which much was written in the 19th Century: “Ancient Forts 1 and 2, Newburg.”

“Ancient Forts 1 and 2, Newburg” (33Cu4, 33Cu5)

For many years time had forgotten the precise location of the earthen enclosure that Charles Whittlesey named “Fort 1 Newburg.” The best that could be said about the fort site was that it was in the old Newburgh Township, a part of the county that was annexed by the city of Cleveland around 1880. The leading theory relating the site to 20th Century landmarks placed it in the old Forest Hill Park, an area now in the industrial Cuyahoga River Valley east of the river, west of Independence Road, south of Pershing Avenue and north of Washington Park. This approximation of the site’s location is understandable because it does resemble Whittlesey’s survey of the location (Figure A) in that there is a north facing narrow promontory south of a small stream with deep ravines on the east and west sides. This theory of the earthworks’ location however omitted a key piece of evidence prominent in Whittlesey’s survey; that is that the earthworks occupied Lot 313, about one and a half miles southeast of the Forest Hill Park promontory. Eight years after Whittlesey’s 1850 survey this lot consisted of 105.5 acres divided between three landholders. See Figure D. Today the location corresponds to Harvard Grove Cemetery on the banks of Burk Branch stream, just north of Harvard Avenue, and between East 55th and East 65th Streets.

Fort 1 consisted of two earthen walls with two corresponding trenches. See Figure A . When Whittlesey observed the earthworks in the mid-1800s, the walls were so badly weathered that only two feet of their height remained. Whittlesey noted there was an entranceway at the west end of the inner wall. This casts the site’s utility for defense in doubt. Today archaeologists believe that such sites were ceremonial rather than defensive.

Whittlesey also mentioned a mound one fourth to one half mile to the east or southeast of Fort 1. It can be seen in Figure E above. Whittlesey indicated that the mound was 10 feet high in 1847 and quickly disappearing thereafter thanks to agriculture. Today this mound site would be in the Harvard-71st Street- Broadway area. See Figure F below. Interestingly this same area is one of the Cleveland metropolitan region’s oldest area’s for significant early settler habitation and once had working quarries.

Pictures here

Additional pictures here: Another Newburgh prehistoric site well described by Whittlesey is now in Cuyahoga Heights in the Cleveland Metroparks Ohio and Erie Canal Reservation. Whittlesey named this site Ancient Fort #2, Newburg. Today the site corresponds to a park location on the western bluffs of the Cuyahoga River floodplain. This places the site just northwest of the main park entrance at East 49th Street and Whittlesey Way. This location fits Whittlesey’s description that the site be one and a half miles downstream of Ohio and Erie Canal Mile Marker 8 Lock, also known as Willow Lock or Lock 40. Whittlesey gave an additional requirement that the site be on a high isthmus surrounded by ravines on all but the south side. The location near the park entrance fulfills this requirement as well.

Additional pictures here: Another Newburgh prehistoric site well described by Whittlesey is now in Cuyahoga Heights in the Cleveland Metroparks Ohio and Erie Canal Reservation. Whittlesey named this site Ancient Fort #2, Newburg. Today the site corresponds to a park location on the western bluffs of the Cuyahoga River floodplain. This places the site just northwest of the main park entrance at East 49th Street and Whittlesey Way. This location fits Whittlesey’s description that the site be one and a half miles downstream of Ohio and Erie Canal Mile Marker 8 Lock, also known as Willow Lock or Lock 40. Whittlesey gave an additional requirement that the site be on a high isthmus surrounded by ravines on all but the south side. The location near the park entrance fulfills this requirement as well.Like Fort 1 not a trace of the Cuyahoga Heights site remains. Like Fort 1 the Cuyahoga Heights site has never been analyzed and dated. Whittlesey noted the enclosure consisted of a single wall and trench on the land side. Its accessibility was different from Fort 1; at Cuyahoga Heights the wall did not have an opening but the outer trench did. This did not seem like much of an entrance to Whittlesey or to anyone who views his drawing The only other point of access was a narrow passageway along the southern portion of the ravine. Whittlesey noted in 1850 that only five feet of the wall’s height remained, as the site had just recently came under cultivation.

Cleveland’s Most Well Known Indian Mound

Cleveland’s most well-known Indian mound just like the nearby earthen enclosures over time has been flattened. The mound’s builders have never been determined; no-one knows if they were Woodland or Late Prehistoric. The mound site, in the Slavic Village section of Cleveland, is appropriately marked by Mound Avenue on the south. The mound has further been memorilaized by the building of Mound Elementary School just west of old county lot 317 that held the mound. Lot 317 was at least 100 acres and was bounded approximately by Union Avenue on the north, East 65th Street on the east, the future Fleet Avenue on the south and the future Wilson Avenue (present-day East 55th Street) on the west. At the time of Whittlesey’s writing lot 317 was the homestead of Dr. Horace Ackley. The area was still rural until the early 1870s when the city’s expanding Czech population gradually built up the Broadway/ East 55th Street area. An 1874 atlas of Cuyahoga County shows the street layout virtually as it still stands today. Undoubtedly the flattening of the earthworks, cliffs and ravine that accompanied the area’s urbanization dates to the same time period. On Whittlesey’s non-scale map of Cleveland area Indian earthworks, the mound is a dot south of Morgan Run stream.

Timeline Point I, Early Woodland Period: 700 BC – 100 BC, and Moundbuilder Culture near Cleveland

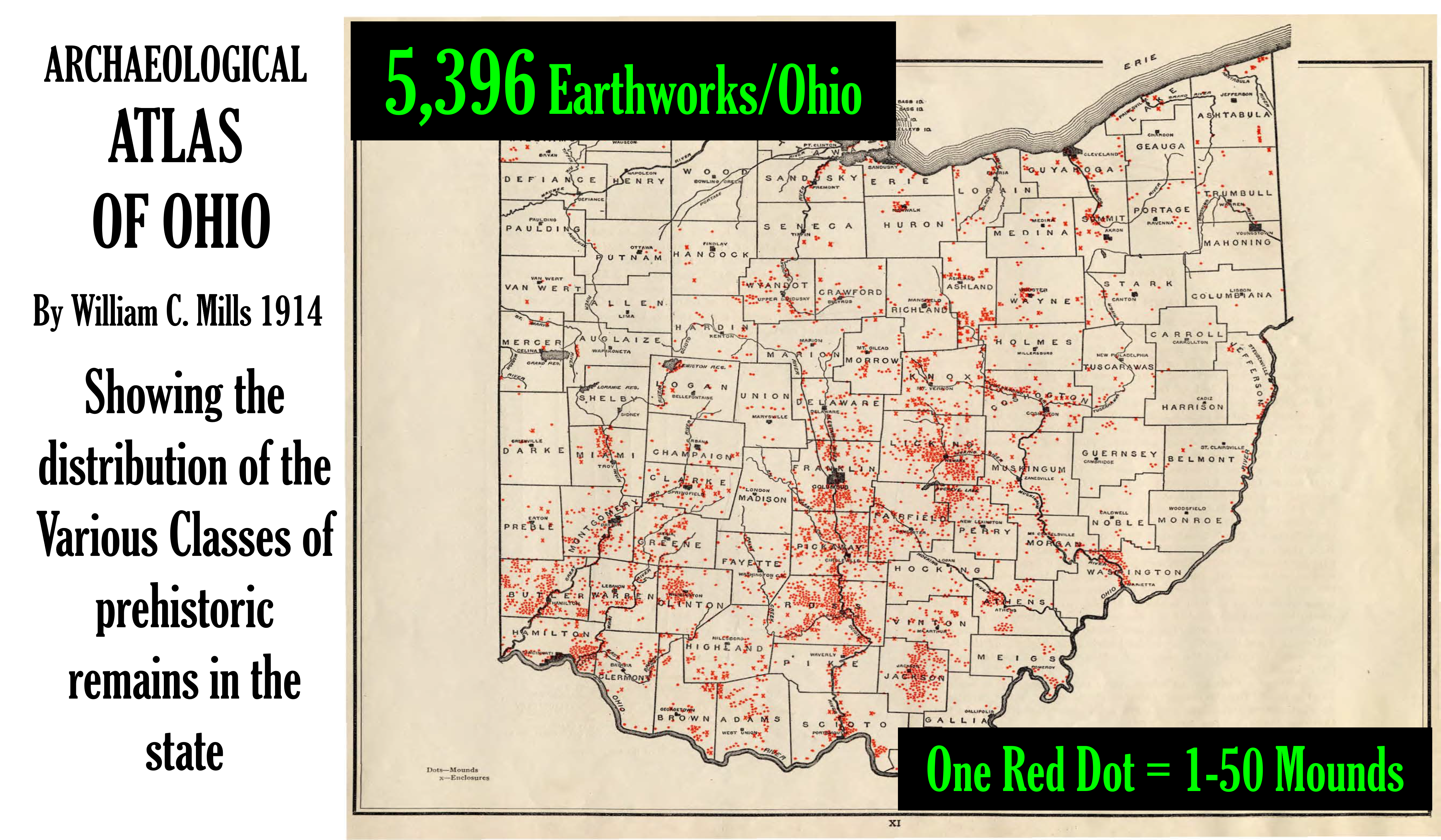

In 1894 when many mounds had not yet been flattened from agriculture, erosion and development, archaeologist W.C. Mills counted 5,396 in the state. The earliest of these mounds belong to Early Woodland people who thrived from 500 BC to 100 AD. In some locales outside of Ohio, burial mounds and pottery showed up in the Late Archaic Period, from 3,000 BC to 1,000 BC.

The Adena people who radiated outward from the Chillicothe, Ohio region had the highest mounds and most elaborate ceremonial culture. The highest Adena mounds were over 70 feet and the widest 300 feet in diameter. Northeast Ohio’s Early Woodland mounds are smaller.

It is important to note that not all Ohio Early Woodland burials involved mounds. Most Early Woodland burials in northern Ohio were not in mounds, but in oval earthen enclosures such as atop steep bluffs of a creek. Seaman’s Fort in Erie County is a good example. There were also Adena burials of this type in southern Ohio and northern Kentucky. One good example is the Colerain Works near present-day Cincinnati.

Many Early Woodland burials contained objects relating to the deceased’s status, both temporal and spiritual. Such buried objects were most commonly projectile points, sandstone tablets (perhaps used for stamping body tattoos) and personal adornments — head dresses, and jewelry such as rings, bracelets and beads. Some burials, probably of lower status individuals, contained no adornments.

Another object sometimes found in Early Woodland burials, including some near Cleveland, is the tubular clay pipe, used for tobacco smoking or as a pipe with which a shaman would suck out evil spirits which they thought were causing symptoms in sick people. This practice involved cutting the sick person, either superficially or enough to let blood, then placing the tube at the point of the cut mark, and sucking. Truthfully smoking and shamanistic sucking have been inextricably bound since Early Woodland times and continue to be so among Native Americans.. A related practice to smoking and shamanistic sucking is the shamanistic practice of blowing tobacco smoke on a sick person. Symbolically the blowing of smoke signified the transfer of spiritual power from shaman to patient. A shaman sucking out disease through a similar pipe was viewed as likewise transferring power. As inhaling and exhaling go together in smoking, sucking out disease and blowing medicine (smoke) go together in shamanistic practice. Thus the tube pipe, whether designed for smoking or sucking, was a sacred object with significance for mortuary practice and the afterlife. The width and construction of the end of the tube pipes and the materials with which they were made offer clues as to whether individual specimens were used for smoking or sucking.

Another important trait of the Early Woodland Period in Ohio is the commencement of pottery in this region. It was mainly simple and thick walled. Such a pottery found in Northern Ohio that shows little Adena influence is the Leimbach type after the Leimbach archaeological site on the Vermillion River in Lorain County. Leimbach ware in Northeast Ohio exhibited cordmarking on the outside. Cordmarking is a feature of much Woodland pottery. It refers to a pottery surface that was texturized with a wooden paddle wrapped with cord. Whatever purely decorative function cordmarking may have served, it also, from a strictly practical standpoint, made pottery easier to handle and harder to drop.

The Leimbach ware also has massive crude rectangular lug- type handles not found on Adena pottery. Some archaeologists think the Leimbach ware’s simple design reflects its utilitarian, non-ceremonial nature as well as the fact that specimens were designed as single-use items. In contrast some Adena pottery was used for ceremonial purposes. Adena pottery such as Adena Plain and Montgomery Incised was sleeker and more stylized. Very little if any of this fancier pottery has been found in Northeast Ohio.

Additional attributes of the Early Woodland people include but are not limited to:

a) elliptical or hyperbolic shaped ornaments for hanging as pendants. These are often referred to as gorgets. This term is however misleading because they were not body armor. In fact Adena people scarcely knew war; their world is considered a peaceful one.

b) exotic materials obtained through a large trade network

— native copper from present-day northern Michigan, often made into beads, bracelets and rings.

–marine shells from Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Mexico, often fashioned into, but not limited to, spherical beads.

For an example of an Adena shell artifact more elaborate than a bead, look to the Adena Mound in Chillicothe, Ohio.

A realistic portrait in shell of a raccoon was found there– mica from southern Appalachia. While rarely creating such elaborate form as the later Hopewell people’s famous mica representations of human hands and faces to name a few artifacts, the Adena often cut the mica into simpler shapes such as crescents which were used in a plume-like manner in head-dresses, or pierced and worn on necklaces . If the Adena had had more mica, they might have put it to greater use. By contrast one later mound in Hopewell Culture National Historical Park yielded 3,000 sheets of mica !!

Most of the Early Woodland people in Northern Ohio were not Adena but other moundbuilders. The Woodland people, Early, Middle and Late, occupied what became the Eastern United States. Most Early Woodland people did not participate in the Adena cultural revolution. For these non-Adena Early Woodland people, life continued much as it had for centuries. Food continued to be procured by hunting and gathering if of a more sedentary type supplemented by agricultural experimentation with squash and more efficient use of native grain resources such as maygrass. Cultivation of maize was very limited though experimentation with it probably occurred.

For Adena people some key lifestyle changes occurred. The Adena culture saw the beginning in Ohio of a true sedentary lifestyle and agriculture that included the cultivation of maize. Still wild foods remained an important part of the diet. For example Adena people ate hickory nuts, black walnuts and beechnuts Some of these nuts were in the process of being replaced by local grains. Native maygrass was one of the first cultivated Ohio grains. Its seeds though small were ready in spring, much earlier than many previous dietary staples. Another small seeded, labor intensive early grain enjoyed by Adena was goosefoot, related to the South American grain quinoa.

The Koth Cache (33Cu58)

Quantities of Adena artifacts with neither skeletons nor mounds have been found in Ohio wetlands. Such concentrations of material goods are called caches. These are usually found in boggy areas that may have been wetter in former times. Prehistoric people may have lowered items into the water for ceremonial purposes. Sometimes remains of the vessels which held the items are found with the cache.

The Luchens Cache in Portage County, a particularly large one in Northeast Ohio, contained over 300 trademark Adena leaf-shaped flint blades This type of blade is considered to be as much ceremonial as functional. The bog where found is thought to have been an actual lake in Adena times. Also found were remains of a wooden bucket which is thought to have held the blades. In Cuyahoga County is the remarkably little known Koth Cache which yielded 150 leaf shaped blades.

Koth’s Cache was found on high ground in the Cuyahoga Valley south of Tinker’s Creek and east of the Cuyahoga River. The location is currently in the National Park, north of Alexander Road. At the time of the find, the 1930s, the area was described as boggy.

Specific Early Woodland Mounds and Sites around Cleveland

The most spectacular Cleveland area earthworks are surprisingly little known to many area residents. The prehistoric embankments are still sufficiently high as to be easily viewed. The site is Indian Point(33La2) located at the juncture of the Grand River and Paine Creek just east of Painesville, Ohio. The site is now part of the Lake Metropark system. The archaeological community, who has been interested in the area long before it became a park, calls it the Lyman Site because it is on the former grounds of a military training camp operated by Charles Lyman. The site consists of three earthen enclosures atop a steep river bluff. (The western set of walls is severely eroded but the eastern two are easily viewed.) Indian Point did not have mounds; mound-like structures found there have more recently been determined not to be of prehistoric human origin. Until recently the Early Woodland date of Indian Point was not recognized; it was considered strictly a Late Prehistoric site (900 AD-1650 AD) because of the large amount of ceramics and bone tools of this period found there.

Archaeologist James Murphy has long obtained radiocarbon dates prior to the First Millennium AD. He tested remains of cooking fires from deep within the inner earthworks. He also found an Early Woodland Stemmed point. The dates of specific portions of the site including the earthen walls still remain a matter of controversy. Murphy has proposed that the two sets of earthworks may have been constructed at different times.

Early Woodland site: Garlick Mound,33Cu3, Cleveland, Ohio This mound was at the southeast corner of East Ninth Street and Euclid Avenue on the future site of the Wesleyan Methodist Church built in 1839. The site has been known since the first decade of the 20th Century as the location of the George Post-designed Cleveland Trust Company. Landowner Dr. Theodatus Garlick and his brother Abel partially opened the mound in 1820. A slate piercing tool and slate gorget were recovered .

The Garlick property where an Early Woodland mound stood was close to the Erie Street Cemetery founded in 1826. Abel B. Garlick was a well-known Cleveland stone cutter who made gravestones similar to the ones pictured here from the cemetery. Garlick worked the fine-grained Euclid bluestone available on Mill Creek in Newburgh Township southeast of Cleveland. He particularly favored stone from a quarry owned by Dr. David Long, a neighbor and stone house builder to another early Clevelander with a mound on his property– Erastus Gaylord. (See Gaylord Mound below.) Garlick may have also made millstones. The Garlick brothers, Abel and Theodatus were natives of Vermont who came to Cleveland in the young town’s second decade of history. (Photo: Clay Herrick “Erie Street Cemetery and Gray’s Armory” 1978, used courtesy of the C. Herrick Slide Collection of the Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University.)

Early Woodland site: Gaylord Mound, Cleveland, Ohio. This was a mound at 374 Woodland Avenue, the 11 acre country estate of the Erastus Gaylord family. Erastus Gaylord came to Cleveland from Connecticut in 1834 and established Cleveland’s first pharmacy Stickland and Gaylord. (Erastus perhaps is better known along with members of the Severance family, his neighbors on Woodland Avenue, as a founder of the Canal Bank, a troubled and dishonest Mid 19thCentury financial house which served Ohio and Erie Canal shippers.) In the late 1800s, a member of the Gaylord family retrieved from the mound an “Adena type” projectile point of eight inches in length. The only other known archaeological investigation of the area which yielded prehistoric findings merely turned up unfinished or broken tools from local cherts. There was not enough information from the finds for temporal and cultural assignment. The street number changes of 1905-1906 place the mound in the 3200 block of present-day Woodland Avenue. The mound’s environs have been highly developed for the last 100 years. A gas station occupied the property from about 1922 to 1973. Directly to the east was the St. Ann’s Maternity Hospital/ DePaul Infant Home. Since 1973 the site has belonged to Cuyahoga Community College and has comprised a park and recreation buffer zone between college facilities to the west and the dilapidated Longwood public housing complex on the east. From 2004 to 2009 the Finch Group, who are known for beautiful work at the luxurious Park Lane Villa in University Circle, tore down Longwood and launched a national award-winning innovation in public housing called the New Arbor Park Village. The colorful, gleaming complex simulates vibrant city blocks of mixed development. The mound site is under construction as of 2010 for a parking lot for nearby college buildings that are also under construction.

Early Woodland site: Sawtell (Avenue) mound, 33Cu6, Cleveland, Ohio. This mound was located at East 53rd Street and Woodland Avenues. The part of Sawtell Avenue that it occupied no longer exists. The one block of the street that still remains is appropriately called Sawtell Court. The mound site is now part of the Ohio Food Terminal facility. An alley leading from Crayton Avenue to the vicinity of the mound site is fittingly named Indianola.

A 19th Century viewer stated that the Sawtell Mound was five feet high, 40 feet long and 25 feet wide. Whittlesey and Judge C.C. Baldwin, also active in the Western Reserve Historical Society, opened the mound slightly in 1870. They found ornamental beads, copper rings, a spherical hematite gorget and a clay tube pipe. Andrew Freese, the owner of the land with the mound, did not want it destroyed, so no further investigation was conducted at that time. The mound was finally opened entirely in 1909. The report of the mound’s excavation did not take note of what was found, but said a few items were donated to the Western Reserve Historical Society.

Early Woodland site: Collinwood Mound Although the exact location of this prehistoric work has been lost to time, a logical choice would be where St. Clair Avenue meets Euclid Creek. In 1851 when the Lakeshore Railroad was being constructed, a large tubular tobacco pipestem was found in the mound. It was in the range of three to eight inches long. A clay ball was found inside it. Archaeologist MC Read, who first reported the finding, thought it was used as a horn. He may have been mistaken; sometimes Early Woodland smokers of clay tube pipes placed small pebbles and the like inside the pipes to keep the smoking materials from coming out. Still Read tested his Collinwood find out as a horn and found it worked quite well. He also referred the reader to prolific archaeologist and naturalist Charles Conrad Abbott who had had similar experiences with like pipestems found in New Jersey. Abbott noted blowing on the pipestems he found would produce a noise so shrill it could be heard for a good ways away. He then hypothesized that Indians had used broken tobacco pipestems as sound signaling devices over vast distances.

Charles Whittlesey reported that the clay tube pipe taken from the Sawtell Avenue Mound was a “whistle.” His description and picture of it give no indication why he thought it was a musical instrument and not a pipe. Whittlesey did not indicate it was broken. Whittlesey did however mention that he had seen other such pipes or pipestems employed as whistles because they had flute-like holes on the side.

Recent accounts of the pipestems being used as whistles among prehistoric inhabitants of Ohio are wanting. In fact the few other mentions in the recent archaeological literature of clay tobacco pipestems being recycled into whistles pertain to the occurrence among the17th and 18th Century Dutch and English.

Excavations at 17th Century Dutch Colonial Fort Orange in upstate New York revealed that colonists made good use of broken white clay tobacco pipe stems; they drilled or carved blow-holes into the fragments and used them perhaps for signaling, but chiefly for musical entertainment. Archaeologist P.R. Huey found over 30 of them.

Early Woodland (or perhaps Middle Woodland) site: Dundon Mound, 33Cu255, Hunting Valley, Ohio. The site is west of the Hunting Valley Village Hall, and south of the University Upper School campus. As of 1980 the Dundon Mound was over four feet tall and forty feet wide.

Early Woodland site: Wing Farm(no OAI number), Auburn Township, Geauga County. The site is in the vicinity of Wing Road- south of Stafford Road, east of Munn Road, west of Auburn Road, north of Washington Street. There are perhaps fewer Early to Middle Woodland archeological artifacts from Geauga County than the Northeast Ohio counties of Cuyahoga, Lake and Summit. Geauga County is further northeast of the epicenter of Moundbuilder culture in Chillicothe, Ohio. Wing Road is appropriately in the southwest part of Geauga County. The Cuyahoga River is not far off.. The Geauga County Historical Society has recently cataloged its prehistoric artifacts, and found many Woodland age items coming from Wing Road area. Some large Early and Middle Woodland projectile points were found there. Some were brought up during plowing over the decades.

Early Woodland Site: Parkman Mound, 33Ge2, Parkman Township, Ohio. The extreme southeast of Geauga County would be too far from Cleveland for inclusion here if it weren’t for a combination of standout natural features that have made this locale attractive to humans throughout the ages. Here lie the headwaters of the Grand River above which tower massive cliffs. Nearby is a salt seep. All around are quarries. The Nelson Ledges quarrying area is just two miles to the southeast. In fact the prehistoric human occupation of this area seemed to revolve around stone. The Parkman burial mound contained large stones to separate graves and smaller ones that furnished level surfaces or pavements on which to construct the crypts.

The Parkman and Nelson Township stone outcrops are part of the Berea Sandstone formation. Nearby Nelson-Kennedy Ledges State Park has rockshelters where Native Americans are believed to have dwelt in all eras. Within a two mile radius of the Parkman Mound in a non-public location within Geauga County is the Mohawk Rockshelter which has yielded Early Woodland Leimbach Plain sherds.

Cornelius Baldwin of the Western Reserve Historical Society excavated the Parkman Mound in 1879. He described it as at that point in a state of ruin, having been looted numerous times by relic seekers. The best information he could get from longtime residents was that the mound before disturbance was eight feet high, 60 feet long and 15 feet wide. In addition to the stone crypts, Baldwin found projectile points and slate gorgets in the mound. From what he was able to gather from area residents who had looted the site over the years, they had had similar findings of relics.

Early Woodland Site: Chagrin Mound 1, 33Cu2, Hunting Valley, Ohio. (No-one ever recorded the exact latitude and longitude coordinates for this site. Hobbyists living on the property or adjacent properties conducted the dig.)

The site also has a companion mound to which has been assigned a Hopewell cultural affiliation. See Hopewell sites on this webpage. The Chagrin Mounds, 1 and 2, were on the old Orange Township homestead of James Graham. Today the property would be located just north of the juncture of South Woodland (Ohio 87) and Falls Road. It is just northeast, across South Woodland Road from the Cleveland Metroparks’ South Chagrin Reservation.

Robert Graham, James’s brother, along with a neighbor opened Mound 1 in 1878. Stone slabs covered a central burial. There was red ochre or hematite in the mound and slate elliptical shaped gorgets were recovered. Red ochre burials with gorgets in fact in Ohio go back to Archaic times. Archaeologists believe that prehistoric Indians found red ochre sacred. They note that sprinkling a corpse with red ochre was part of Early Woodland mortuary ritual. Furthering an assignment of the site to the Early Woodland period were finely chiseled Robbins points.

The Chagrin mounds and surrounding area were rich in artifacts. Robert Graham was a prolific Indian relic collector in the late 1800s with a collection of around 2,000 objects. A few pieces from the 1878 excavation, such as a six by six inch piece of mica, found their way into museum collections shortly thereafter. The Grahams kept most of the numerous artifacts from both of the Chagrin mounds in a private museum on their property. The collection included in addition to gorgets beads, knives, projectile points, grinding stones and all sorts of other tools and ceremonial objects. After Graham’s death in 1817, Graham’s collection was donated to an Ohio museum. This was a move that furthered science. Over the years archaeologists have gleened beneficial information from Graham’s former collection.

Early Woodland site: Southern Solon. In an unnamed locale in this area at an unknown date a farmer while plowing brought up an eight inch “Adena-type” projectile point. In and of itself, this finding is not significant. Probably agriculture has led to most amateur finds of prehistoric materials. What may be interesting about this finding is that it is in the open accessions catalog of an important regional museum. This study includes this site mainly to illustrate the breadth of what has been found and where findings may be kept.

Early Woodland/ Archaic sites: Merkle 1 and 2, 33Cu38, 33Cu41, Independence, Ohio. This is one of several sites that were revealed by the 1975 installation of the Cuyahoga Valley Interceptor Sewer and the archaeological survey connected to the sewer upgrade. Like most of the other sites uncovered during the sewer project, Merkle consists of campsites at the point where the Cuyahoga River bluff meets the river’s floodplain. (See topographical map below.)

Woodland site or not manmade at all. Now we journey to Avon, Ohio, to the southeast corner of the intersection of State Routes 83 and 254; this is the site of the Avon Cemetery. Local legend has it that this cemetery was built on the site of an Indian mound. There is a large hill of earth in the cemetery, predating it, that resembles an Indian mound. In 1900 the sexton of the cemetery, Alfred Walker, reported finding projectile points and beads in the mound. His motivation for this report or what he actually found and how it got there remain a mystery. The mound has not piqued the interest of professional archaeologists.

Those most knowledgeable believe that the mound is thousands of years old and came into existence naturally. The last ice age created a glacial lake, Lake Warren, of which Lake Erie is one portion. Lake Warren partially dried up in the hotter Xerothermic period 4,000 to 8,000 years ago, following the retreat of the glaciers. In Avon, Ohio the new shoreline after Lake Warren’s retreat corresponds to that of present-day Lake Erie. It is hypothesized that the cemetery mound was a sand dune on a beach of ancient Lake Warren. Certainly the location is plausible. It is south of the North Ridge, the former location of Detroit Road. Prior to European settlement, the North Ridge had marked the boundary of the former lake Warren and also had been the site of an ancient path which the early Detroit Road followed.

Timeline Point II, The Middle Woodland Period: 100 BC – 700 AD, and Hopewell Mound Culture near Cleveland

Before delving into the specifics of Hopewell Culture, it is necessary to point out that Hopewell culture was not the only Middle Woodland culture in Northeast Ohio. However other Middle Woodland cultures, besides Hopewell, are hard to detect because life went on much as before. One such Middle Woodland, non-Hopewell site in Northeast Ohio is the

Huntington Road Site (33La160).

The Huntington Road site is in Painesville Township, Ohio. It is on the north bank of the Red Creek just east of where the creek enters the Grand River. This places the site a half mile west of the intersection of Fairport Nursery and Mantle Roads. Chesser and Snyder projectile points were found there. These were used by a number of Middle Woodland people besides the Hopewell. The pottery recovered from professional digging at Huntington was undecorated. The remains of vegetable matter were mainly nutshells. No evidence of the following prominent Hopewell traits were found:

a) agriculture with emphasis on tobacco

b) ample earthen enclosures of a more elaborate nature than Adena predecessors 2.

c) continent-wide trade networked) a wider variety and more elaborate decoration in functional art including pottery The Hopewell people (100-700 AD) were more agricultural and sedentary than their Adena predecessors. The large number of tobacco pipes that have been found in their burials suggest extensive tobacco farming. The characteristic Hopewell tobacco pipe is the animal effigy platform pipe. These pipes are truly works of art where the Hopewell displayed fine detail and realism. It would not be an exaggeration to say that among the Hopewell platform pipes found, hundreds of different animals and birds were depicted. This interest in animals was probably not mere design; it represented the elaborate spiritual belief system governing every aspect of Hopewell life. The Hopewell trade network was discriminating and extensive. The Hopewell people obtained obsidian from the Colorado area, marine shell from the Gulf of Mexico, native silver from Canada, large supplies of copper from upper Michigan and sizable quantities of mica from Appalachia. What materials from the Hopewell epicenter of Ohio the Hopewell in turn traded to others is less clear. The main native Hopewell material that has been found far away from Ohio was flint from Flint Ridge, a quarrying area in Licking County, southwest of what is now Newark. Archaeologist Brad Lepper thinks demand for this mediocre quality flint may have been for its “swirly”, multicolored appearance which may have assumed spiritual characteristics in the same way light-throwing mica did . People have marveled at the skill and imagination with which the Hopewell worked copper. The Hopewell hammered the native metal into highly decorative armor. One particularly ornate piece is a double eagle breastplate recovered at a Michigan Hopewell site. Similarly in the museum at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park there is a hammered copper three dimensional bear or pig that is believed to have been part of a headdress.

The Hopewell made their beautiful pottery without the aid of even a rudimentary potter’s wheel. They continued to use the stacked coil method of Adena times. The Hopewell also continued to cordmark their pottery and employed new decorative techniques such as stamping special ceremonial pieces with wood carvings.The perhaps most well known and most exquisite northern Ohio Hopewell artifact is an effigy-pipe found in the Esch Mound in Huron County. Though highly stylized, the effigy may represent an alligator. Like other Woodland Indians, the Hopewell built ceremonial earthen enclosures, near which mounds were sometimes located. At one time archaeologists thought Hopewell earthworks were built primarily for defense but recently have backed away from that hypothesis. For example at Ohio’s Fort Ancient and other Hopewell earthworks, trenches and moats were inside rather than outside the enclosure, and thus could not have served a defensive purpose.

Some Hopewell earthworks exhibited complex features not seen in earlier enclosures. For example some were built in an octagonal shape such as the Newark Octagon. Some earthworks served as calendars, both solar and lunar. This is true of Fort Ancient in Southwestern Ohio.

North Benton Mound

One Hopewell mound burial in Northeastern Ohio near Alliance in Mahoning County had an unusual and intriguing feature: Inside the earth mound some of the burials were organized around a floor mosaic in the shape of an eagle spreading its wings. The effigy was first sculpted in puddled clay; then white stones were laid over the clay form. The effigy was 32 feet by 16 feet in size. This Hopewell burial site is also known more picturesquely as the Temple of the Effigy. The eagle may have represented a particular Hopewell clan as other animal and bird imagery in burials represented other clans.

In Chillicothe, Ohio, the epicenter of Hopewell activity, archaeologists have found stone mosaic effigies on floors of mounds. In addition animal effigies made out of larger stones have been found directly under the outer layer of mounds’ soil.

Specific Hopewell Mounds and Sites around Cleveland

Hopewell sites in Northern Ohio are few and far between. There are other less elaborate Middle Woodland sites in the area, such as the previously described Huntington Road site that fairly could not be considered Hopewell. The following attempts to be a reasonably complete list of truly Hopewell sites in Cuyahoga County and beyond. Hopewell site: Chagrin Mound 2, 33Cu2, Hunting Valley. This site also has a companion mound, Chagrin Mound 1 to which has been assigned an Adena cultural affiliation See Chagrin Mound 1 under Adena sites on this webpage for more precise site location infomation. Chagrin Mound 2 was also on James Graham’s property. On Sunday October 24, 1886 Robert Graham and family invited fellow relic collectors to the property for excavation of Mound 2. (The literature does not note whether Mound 2 was investigated prior to this date as well.) The dig was undertaken chiefly in a hobbiest spirit and in the interest of swelling the Grahams’ private artifact museum. A local newspaper reported that “the neighbors served refreshments and all reported a fine time.” The main evidence for assigning this mound to the Hopewell culture is the particular points found there. They displayed corner-notching and were made from the preferred pink and white flint from the Flint Ridge near what is now Newark, Ohio. Also contributing to the Hopewell identification were “a finely wrought pipe”, a piece of galena, a perforated piece of sandstone, several knives of chalcedony, and some stone discs found in the mound. One collector, known only as R. Evans, donated one of the knives to a local museum. See picture below.

Hopewell site (or perhaps Adena): The Holtkamp Site, 33Cu78, Bentleyville, Ohio. This site with a colorful history overlooks the Chagrin River just south of where the river’s two branches split. The site was originally on Julius Kent’s land, several hundred feet southeast of his palatial residence. While the house if it still stood today would be on the west side of the Chagrin River in the metropark near the marked vistas for the bridal trail, the mound was on the portion of his property on the east side of the Chagrin River. Alltogether this property, that included land on both sides of the river, was 211 acres in 1878. Its legal designation was Chagrin Falls Township Lot 4.

By 1878 Martin Bentley owned the land. By the 1900s the Foster family had acquired the property with the mound. Today it abuts Cleveland Metroparks’ South Chagrin reservation. The site consists of a mound that was opened in about 1840. Four stone unlidded coffins were found. One was child sized. The others were built for adults of larger size than the Indians that European settlers had encountered. Their large size and sophisticated stone technology, similar to certain other moundbuilders relics, fuelled prominent 19th Century racist ideology. This theorized incorrectly that the Ohio moundbuilders were somehow related to the Egyptians or members of other great Eurasian civilizations, perhaps a lost tribe of Israel. Euro-Americans who held such notions were also likely to be among the large group of believers that historic Indians encountered by Europeans were indeed “savage” and had wiped out the Moundbuilders.

The idea that the historic Indians were actually descended from the moundbuilders struggled to find an audience in the early19th Century. Crisfield Johnson, editor of History of Cuyahoga County, the source on the Chagrin “Crypt”, writing in 1879, voiced the more modern opinion, that the moundbuilders were in fact ancestors of historic Indians. This author however in his article also mentioned the competing idea that the moundbuilders were an “advanced” group unrelated to historic American Indians.

Perhaps the reason that the mound was first opened in 1840 but only added to a regional history some 39 years later was that in 1878 another excavation was undertaken at the mound and written up in a local newspaper. This later dig revealed a fifth coffin and also banded slate gorgets and at least one projectile point. The literature on the 1840 excavation mentioned no artifacts.

In the early 1900s prominent citizens Howard and Homer Foster attempted to do additional explorations at the mound site, but being superstitious types, curtailed their efforts only after a little digging; they thought they heard strange noises coming from the mound. As of the 1970s the mound stood over eight feet high and 20 feet wide.

Hopewell or Middle Woodland site: Gleeson Mound and Gleeson Village, 33Cu19, Valley View, Ohio. These sites are east of the Cuyahoga River and Canal Towpath. One is on the north side of Gleeson Drive, and the other is on the south side. They are not far from the Valley View municipal complex on Hathaway Road. Due to agriculture, not much of a mound remains. Snyder’s projectile points, indicative of Middle Woodland but not necessarily Hopewell occupation, were found at Gleeson’s Mound. Hopewell diagnostic ceramics were found at nearby Gleeson Village.

Hopewell site: Everett Mound, 33Su14. The Cleveland area’s most spectacular Hopewell site is the Everett Mound. It is in northern Summit County in the Cuyahoga Valley National Park. It is on a creek bluff off Everett Road on the north side of the Everett Covered Bridge and on the north side of Furnace Run creek. Less than a mile to the east is the Cuyahoga River, Riverview Road and the Ohio and Erie Canal/ Towpath. In 1856 during excavations to build a schoolhouse, copper tools, many sheets of mica and most interestingly a mound with a crypt-like hexagonal limestone enclosure were found at the site. MC Read in his important archaeological work of 1888, gave the location special attention. Whittlesey may have also taken note of it.

Archaeologist David Brose professionally excavated the Everett Mound site in 1974. He did not find native copper tools or additional quantities of mica, but did salvage artifacts which further corroborate a Hopewell association for the site. For example Brose found pottery sherds similar to those from major Hopewell sites downstate such as the Seip Mound in Bainbridge, Ohio and the elaborate Turner Mound group in Hamilton County, Ohio

Timeline Point III, The Late Woodland Period near Cleveland: 500 AD – 900 AD

The land area corresponding to Northeast Ohio played a more prominent role in the Late Woodland Period than in the Early or Middle Woodland. A Late Woodland period site in Northeast Ohio, Greenwood Village, is one of the most important Late Woodland sites in what is now Ohio 4. The Late Woodland period occurred in last part of the first in Millennium AD, around the time of the perhaps parallel European “Dark Ages.” One possible reason for Woodland cultural decline at this time was scarcity of large game. Trade goods from afar such as obsidian vanished. Mica ceremonialism ceased. Art became simple. Yet in the Late Woodland period advancements in agriculture and technology took place, rendering the period no “dark ages” at all. Several important changes in applied technology occurred at the end of Late Woodland Period. One was the decline of maygrass in dietary importance. A second was the rise of underground pits for prolonged food storage. Both of these changes in diet resulted in freeing up energy previously used for food procurement. Pottery changed too by shifting to thinner, simpler types. This shift enabled cooking with pottery to occur at higher temperatures with longer times. In turn porridge became a dietary staple. Fed to infants, porridge enabled them to be weaned earlier; mothers could then have more children; human populations mushroomed. Another sign of progress in the Late Woodland Period was entrance into Ohio of the bow and arrow. Points launched by bows moved more swiftly and could be sent forth in greater succession than those launched by atlatl, the former chief hunting weapon 5. This change allowed for greater hunting success. Additionally bow-launched points had greater impact, further maximizing wild game harvesting.

Military and sacred earthworks continued to be erected in the Late Woodland period. Some Late Woodland and Late Prehistoric Period earthworks have remains of log stockades, and thus are considered to be more defensive than the Hopewell earthworks which preceded them. (Defensive use of the Greenwood Village earthworks is doubted however. See next paragraph) Burial mounds continued to be built though their building material transitioned from earth to stone. Grave goods became few and far between.

Late Woodland site: Greenwood Village, 33Su93, Sagamore Hills, Ohio.Greenwood Village is located atop a high narrow wooded plateau east of the Cuyahoga River and south of the intersection of Route 82 and Holzhauer Roads in present-day Sagamore Hills, Summit County. The site is within national park boundaries. In the 1970s archaeologists conducting reconnaissance in the Cuyahoga Valley realized that Greenwood Village corresponded to a site Charles Whittlesey had extensively described in the 19th Century and named Whittlesey Fort #5. (It is easy to overlook the site based on Whittlesey’s description because the earthen embankments he reported are now only two feet high.) Whittlesey himself, though naming the site a “fort”, had doubts to its military character:”There are no evidences of attacks by a foe, or of the destruction or overthrow of any of them….” He wrote. Archaeologist Stephanie Belovich, a chief excavator of the Greenwood site, found posthole-mold evidence of wooden palisades in front of certain of the earthen walls. Though these in a cursory analysis could be assumed to be ramparts, Belovich, also finding no further evidence of military activity at Greenwood, and substantial evidence of an erosion problem, theorized that the wooden structure was used in prehistoric times to forestall erosion. One piece evidence that the site may have been ceremonial rather than defensive lies in the fact that, as with other “Whittlesey Forts,” the users could have easily walked right in. Secondly evidence of domestic activity is limited to fire-pits used only a short time. There would have been no need to fortify such an area. On the other hand erosion has been an ongoing problem at the Greenwood site. It has been such a problem with increased use of the site in historic times that the plateau is even much narrower than it had been in Whittlesey’s day. Belovich in her survey of the area, strongly suspected that the two earth mounds that Whittlesey reported there were now part of a large slippage slope 20 feet lower than the rest of the plateau. The latest archaeological evidence gathered at Greenwood, largely by Belovich, challenge early 1970s evidence from a larger general area that Greenwood was primarily used in the Late Prehistoric period. Belovich finally found a stone floor reported by Whittlesey. Archaeologists often associate such use of stone in Ohio with the Woodland period. For example Fort Ancient, a Hopewell enclosure in southwest Ohio, has ample stone pavements. The radiocarbon dates obtained for Greenwood in the 1980s corresponded to a few centuries later with a mean date of 750 AD. The Greenwood stone artifacts by that time, the Early Late Woodland period, were in turn more simple than any Hopewell artifacts. Another feature of Greenwood is trademark Late Woodland pottery lacking decoration. The particular projectile point styles found also correspond to the Late Woodland. Nor is Greenwood Village an isolated Late Woodland phenomenon in the Cuyahoga Valley. At least one other nearby site has yielded lithic assemblages of similar appearance

Late Woodland site: Fort Hill, OH57. This site is in present-day North Olmsted, Ohio overlooking the Rocky River in Rocky River Metropark. The site consists of three earthen walls that acted to cordon off a point of land surrounded on the other three sides by water. The walls date to about 800 AD. Since no post-mold holes for any structure were found at the site, as with Greenwood, it is assumed to be ceremonial, not defensive. There is also evidence at Fort Hill for later use by Whittlesey people.

Timeline Point IV, The Late Prehistoric Period: 900 AD – 1650 AD, and Whittlesey Culture near Cleveland

The Late Prehistoric period in northern Ohio between the Conneaut River in eastern Ashtabula County and the Black River in Lorain is distinguished by a marked culture that archaeologist Emerson Greenman named the Whittlesey Focus after Charles Whittlesey. Changes in pottery style and a transition to a more sedentary lifestyle characterized the Whittlesey Focus. In some ways the Whittlesey Focus displayed the insularity and isolation of the Late Woodland period. Local flint as opposed to that quarried far away became more popular for points and blades. The Hopewell level of trade was never re-established. Mounds and elaborate burials were rare in the Whittlesey Focus. Yet the Mid-Continental cultural blossoming inspired by Native Mexican developments, and called Mississippian culture, was present in the Whittlesey Focus. Two hallmarks of Mississippian culture seen in Northeast Ohio were rich ceremonialism and continued agricultural advancement. The flowering of Mississippian culture in Ohio is most associated with the Fort Ancient people near the Ohio River. In turn Fort Ancient civilization spread to the Whittlesey Focus and other cultures further north. Through Fort Ancient culture and the Mississippian influence, beans, originally from Mexico, came to dominate northern Ohio agriculture. Maize, also originally from Mexico, showed improved varieties among Whittlesey people. The Reeve Road site suggests increased tobacco culture; more smoking pipes were recovered there than at any other Ohio prehistoric site except the Mound City group, a well-known Hopewell complex in central Ohio.

Pottery found at some Whittlesey sites shows tempering with shell. Shell tempered pottery is more durable and heat resistant than grit-tempered pottery. Handles and stamped designs are other enhancements observed in Whittlesey pottery. Archaeologists found a Fort Ancient influence in the Whittlesey pottery at least four Northeast Ohio sites: Reeve Road, Fairport Harbor, Tuttle Hill and South Park. South Park and perhaps other local Whittlesey sites displayed further Mississippian influence in their elaborate art: Brose unearthed engravings with the trademark Fort Ancient “weeping eyes” as well as statuettes, headdresses and conch shell masks.

Specific Whittlesey Sites in and around Cleveland

Whittlesey site:Reeve Road, 33La4, 33La186, Eastlake, Ohio. Already in the 19th Century Charles Whittlesey knew of this artifact-rich site near the mouth of the Chagrin River in Eastlake, Ohio. In 1888 Whittlesey described the site as on a river bluff 35 feet high. He observed earthen walls of about 660 feet in length. The walls were so worn down as to be barely visible in height. Longtime artifact collectors on the site, the Worden Brothers, informed Whittlesey of two distinct walls about 16 1/2 feet apart in between which there had been a trench. The Wordens gave Whittlesey several bone awls, one of the most numerous artifacts in their collection from the site. Bone awls continued to be a prominent feature of Reeve site excavations which peaked in the 1970s. The Indian Museum of Lake County, a major repository of Reeve artifacts, counts 397 bone awls in their collections. The only Reeve site artifacts in the Museum’s collection more numerous than the awls are flint projectile points of which the Museum owns 707 and pottery sherds of which it holds 1216. Numerous bone awls also characterize the Fairport Harbor Whittlesey site in Lake County. By 1929 the Reeve site had come to the attention of the professional archaeological community. Mid-20th Century excavations revealed the many projectile points and tobacco pipes that now characterize the site. The largest artifact discoveries however were not made until 1973 when the property was sold to a condominium developer and water and gas lines dug. Local collectors descended on the site, taking all of interest that they could find until the site was closed off and the development completed. Several collectors formed the Lake County Chapter of the Ohio Archaeological Society which in 1980 started the Indian Museum of Lake County as a repository and display area for Reeve and other local artifacts.

At least two types of pottery were named after the Reeve Road site, for example Reeve Horizontal and Reeve Filleted. Reeve Horizontal is usually horizontally cordmarked with a distinguishing rim. Reeve’s Filleted is similar but with an additional strip of clay around the rim.

Whittlesey site:Chagrin Long House, Hunting Valley, Ohio. This site is near an unidentified falls of the Chagrin River. This site illustrates Whittlesey construction. (For more information see “Whittlesey Site VI: Board of Education Building.”) Researchers found post-mold holes for a 50-foot long structure.

Whittlesey site:South Park Village, 33Cu8, Independence, Ohio. This site consists of forty acres now in Cuyahoga Valley National Park; they’re on the west side of the Cuyahoga River, south of Tinker’s Creek, north of Pleasant Valley Road. South Park is one of the most revealing Whittlesey sites in Northeast Ohio. It has an extensive literature. The South Park site is so important that the descriptions in this article of both Whittlesey culture and specific sites could not have been written without South Park as a guide. One highlight of South Park is insight into the appearance of Fort Ancient cultural traits in northern Ohio. Extensive pottery with such Fort Ancient influences as handles and symmetrical decoration has been recovered from South Park. Pipes with the weeping eye motif have been found at South Park as well.

Whittlesey site: Tuttle Hill, 33Cu7, Independence, Ohio. This site is east of Brecksville Road (State Route 21), north of Interstate 480, south of Granger Road and west of the Cuyahoga River. This is another of the earthen hilltop enclosures that Charles Whittlesey investigated in the 19th Century. Whittlesey called the site the Ancient Fort #3, Independence. The current name stems from Henry Tuttle, the owner of property in Whittlesey’s time. Twentieth Century industrialization totally wiped out the earthworks, the location of which presently is the Cloverleaf Bowling Alley on Brecksville Road. Whittlesey lamented about the wear from agriculture on the earthwork in his own time, describing the area as “mercilessly cropped.”

Tuttle Hill was the site of Emerson’s Greenman’s 1930 work which identified the Whittlesey Focus. Tuttle Hill also lends its named to a style of pottery which David Brose identified and called Tuttle Hill Notched. This style characterizes much of the pottery in the entire area. Far more of the type was uncovered at the larger nearby South Park Whittlesey site. It is a late pottery style, perhaps as recent as 1650 AD, the era of the last of the Whittlesey people. The style shows likely Fort Ancient influence. It has strap handles and decorations on the lip of the vessels corresponding to the handle points. The rim displays symmetrically placed decoration. The body can be stamped, cordmarked or plain. (To a layman the Tuttle Hill Notched type of pottery looks “fancier” than average Whittlesey pottery, and appear to have a “tee-pee” design on the body.) Despite their late date, and the recovery of well-preserved shell tempered specimens, actually local Tuttle-Notched pieces were not tempered with shell more than the slightly earlier Reeve pottery.