Article Below By Sarah E. Baires, SMITHSONIAN.COM FEBRUARY 23, 2018

“A closer approximation to the Book of Mormon picture of Nephite

culture is seen in the earth and palisade structures of the Hopewell and

Adena culture areas than in the later stately piles of stone in

Mesoamerica” – Hugh Nibley, “Ancient Temples: What Do They

Signify?”, Ensign, Sep. 1972, (see p. 349).

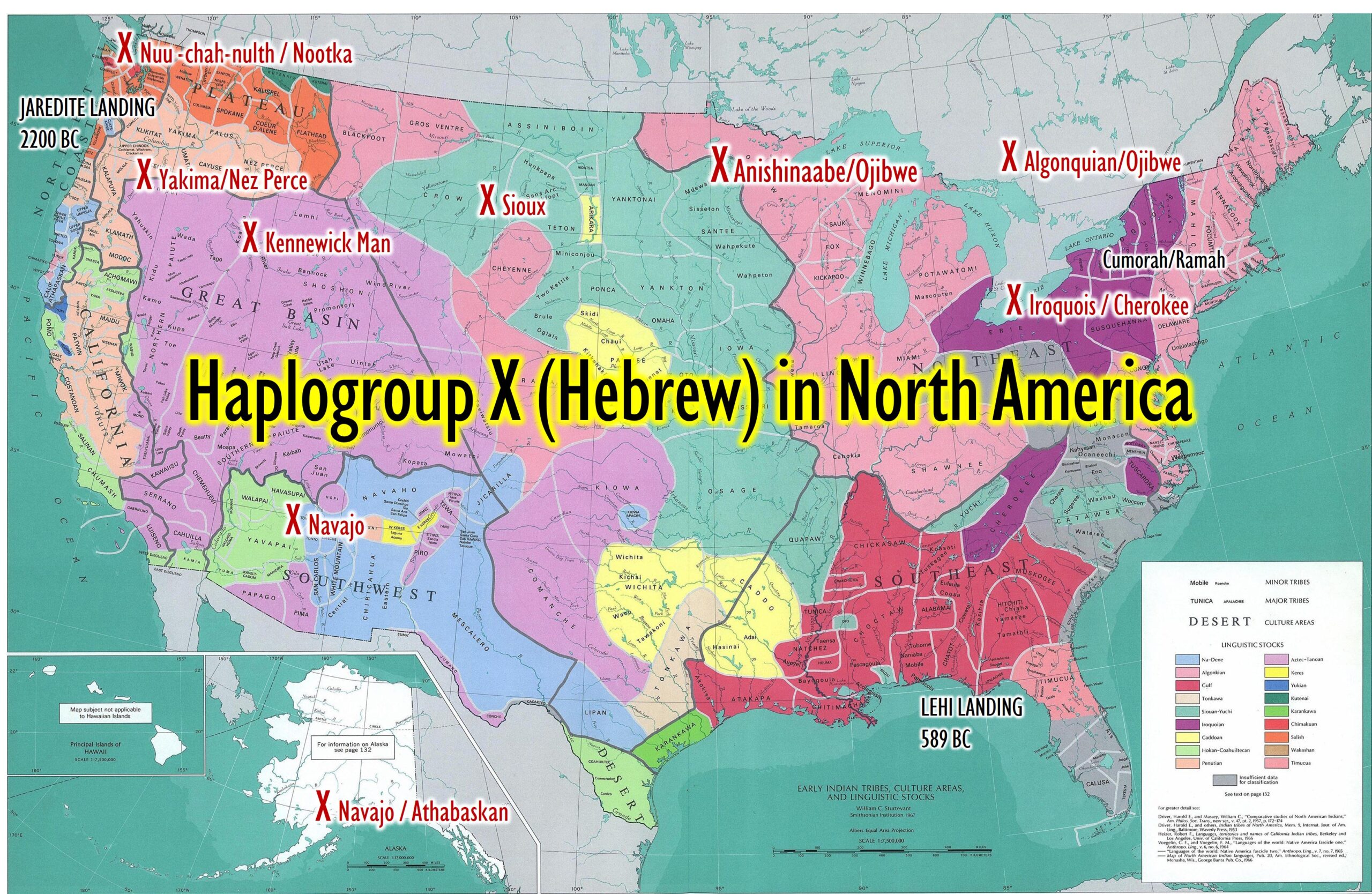

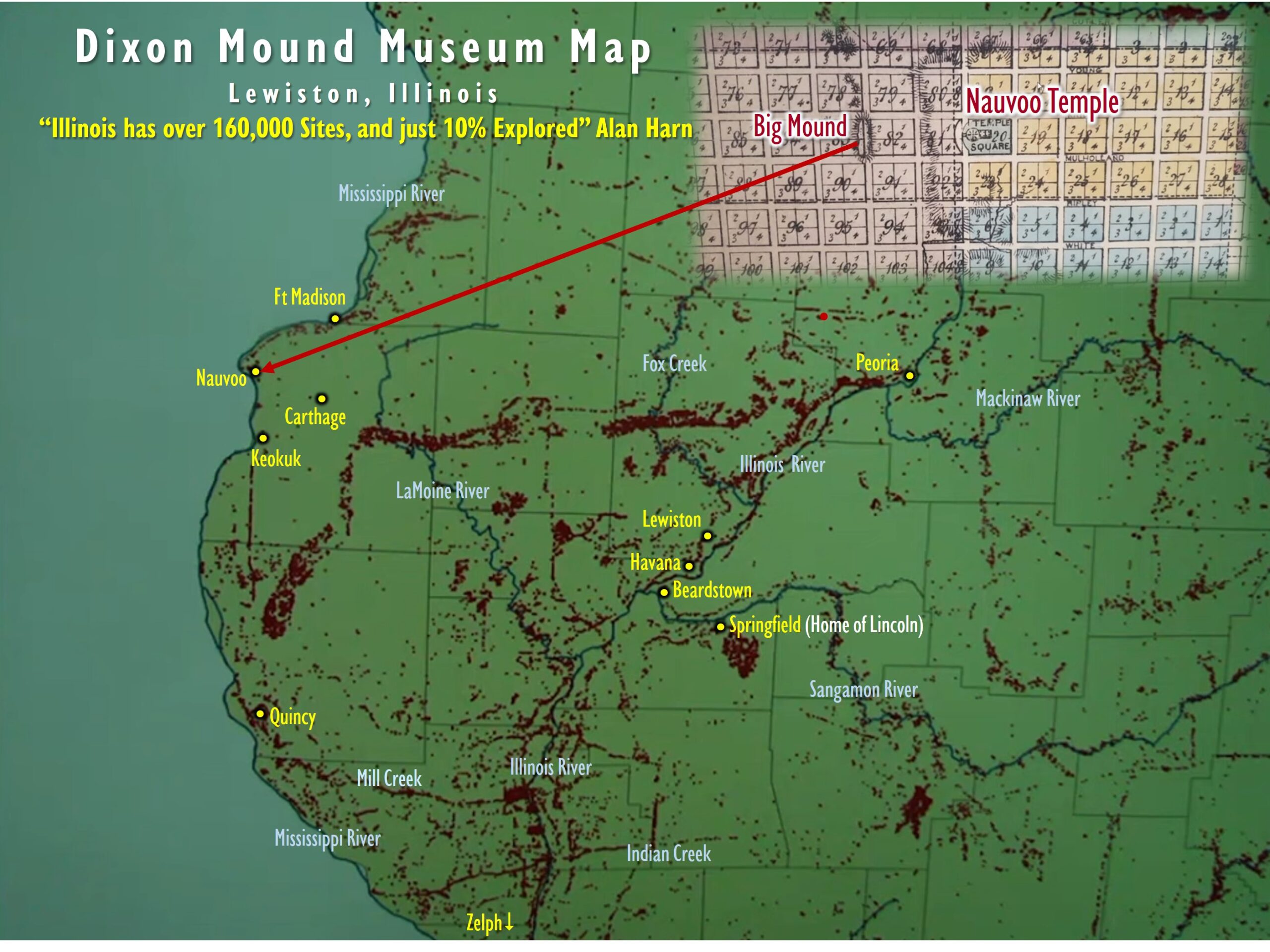

The Hopewell culture describes the common aspects of a segment of Native American culture hat flourished along rivers in the northeastern and Midwestern United States from approximately 400 B.C. to 500 A.D., a time period that nearly matches the span of the developed Nephite societies. The

Hopewell peoples were not a single culture or society, but a widely dispersed set of related populations as shown on the map below.

They were connected by a common network of trade routes, in what is known as the “Hopewell exchange system.” The name ‘Hopewell’ was chosen by Warren K. Moorehead, known as the ‘Dean of American archaeology,’ after his explorations in 1891 and 1892 of a group of mounds in Ross County, Ohio. He named the mounds after Mordecai C. Hopewell, the owner of the land. Subsequently all mounds that have similar identifications are named as the Hopewell Mound Builders within an interaction sphere. Annotated Book of Mormon by David Hocking and Rod Meldrum page 536

Dr. Roger Kennedy, the former director of the Smithsonian’s American History Museum, addressed a misconception about earth mounds, noting that earth mounds are actually buildings. Build and building are also very old words, often used in this text [his book] as they were when the English language was being invented, to denote earthen structures. About 1150, when the word build was first employed in English, it referred to the construction of an earthen grave. Three hundred and fifty years later, an early use of the term to build up was the description of the process by which King Priam of Troy constructed a “big town of bare earth.” So when we refer to the earthworks of the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys as buildings no one should be surprised.” Jonathan Neville Mounds and Mormons

Roger G. Kennedy, Director Emeritus, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, author, “Hidden Cities, The Discovery and Loss of Ancient North American Civilization,” The Free Press, New York, [1995], stated, “Very, very few of us were conscious of these immense cities of a place like Monk’s Mound and Cahokia, opposite St. Louis, which is bigger in its footprint than the Great Pyramid at Giza [city in Egypt]. We didn’t know that.” Dr. Kennedy coined the phrase, “Hidden Cities,” because he states, “I use the term because these were very big places. There were more people, that we now know, in Cahokia, across from St. Louis, than there were in London or Rome. There were major population centers in what is now Nashville and Cincinnati and Pittsburgh and St. Louis. Few realize that some of the most complex structures of ancient archaeology were built in North America, home of some of the most highly advanced and well organized civilizations in the world.”

In his book, Hidden Cities, he writes: “Eighteenth century pioneers passing over the Appalachians into the Ohio Valley wrote often of [the] feeling of being freed of encumbrances, of fresh beginnings. Judging from what they said, and from what has been said of them subsequently, most of them shared the misconception that they were entering an ample emptiness

intended to be theirs alone. “In fact… [t]he western vastness was

not empty. Several hundred thousand people were already there, and

determined to resist invasion….Even along the headwaters of the Ohio, on the banks of mountain brooks, there were signs of ancient habitation…As the streams grew larger, so did the buildings. “In the Ohio and Mississippi valleys, tens of thousands of structures were built between six and sixty-six centuries ago. Some, as large as twenty-five miles in extant, required over three million person hours of labor” – Roger Kennedy, Hidden Cities, 1-2.

Woodland Culture

The term “Woodland Period” was introduced in the 1930’s as a generic term for prehistoric sites falling between the Archaic hunter-gatherers and the agriculturalist Mississippian cultures. This period is characterized with both chronological and cultural manifestations having no massive changes within a short time period, but instead, having a continuous development in the making and use of stone and bone tools, leather crafting, textile

manufacture, cultivation, and shelter construction (McDonald and Woodward, “Indian Mounds of the Atlantic Coast: A Guide from Maine to Florida,” McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company, Newark, OH [1987], 13). Many Woodland peoples used bows and arrows, spears and atlatls, a tool designed to hand cast arrows too large for a bow as shown:

▪ 1000 B.C. to 200 B.C. – Adena culture (proposed Jaredites, p. 453)

▪ 400 B.C. to 500 A.D. – Hopewell culture (proposed Nephites/Lamanites, p. 536)

▪ 700 A.D. – Cahokia settlement first established (Lamanites used as slaves, p. 540)

▪ 750 A.D. to 1100 A.D. – Upper Midwest Effigy Mounds are built

▪ 900 A.D. – Construction of Monks Mound, Eastern U.S.’s largest earth

work, is begun at Cahokia

Mississippian Culture

The Mississippian culture was a mound-building Native American civilization composed of a series of urban settlements and satellite villages linked together by a loose trading network, the largest city being Cahokia, near present day St. Louis, MO, believed to be a major religious center. The civilization flourished from the southern shores of the Great Lakes at Western New York and Western Pennsylvania in what is now the Eastern

Midwest, extending south-southwest into the lower Mississippi Valley and wrapping easterly around the southern foot of the Appalachians barrier range into what is now the Southeastern United States (Bense, Judith A., “Archaeology of the Southeastern United States: Paleoindian to World War I,” Academic Press, New York [1994]).

▪ 900 A.D. – Mississippian Culture establishes Cahokia as their capital

▪ 1050 A.D. – Aztalan is occupied by Mississippians in Wisconsin

▪ 1070 A.D. – Construction of the Great Serpent Effigy Mound in Ohio

▪ 1200 A.D. – Monks Mound is completed at Cahokia

▪ 1400 A.D. – Cahokia is abandoned

▪ 1540 A.D. – Mississippian towns in Ohio are abandoned

See Page 535 of the Annotated Book of Mormon by David Hocking and Rod Meldrum

White Settlers Buried the Truth About the Midwest’s Mysterious Mound Cities By Sarah E. Baires, SMITHSONIAN.COM FEBRUARY 23, 2018

Pioneers and early archaeologists credited distant civilizations, not Native Americans, with building these sophisticated complexes

Around 1100 or 1200 A.D., the largest city north of Mexico was Cahokia, sitting in what is now southern Illinois, across the Mississippi River from St. Louis. Built around 1050 A.D. and occupied through 1400 A.D., Cahokia had a peak population of between 25,000 and 50,000 people. Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, Cahokia was composed of three boroughs (Cahokia, East St. Louis, and St. Louis) connected to each other via waterways and walking trails that extended across the Mississippi River floodplain for some 20 square km. Its population consisted of agriculturalists who grew large amounts of maize, and craft specialists who made beautiful pots, shell jewelry, arrow-points, and flint clay figurines.

The city of Cahokia is one of many large earthen mound complexes that dot the landscapes of the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys and across the Southeast. Despite the preponderance of archaeological evidence that these mound complexes were the work of sophisticated Native American civilizations, this rich history was obscured by the Myth of the Mound Builders, a narrative that arose ostensibly to explain the existence of the mounds. Examining both the history of Cahokia and the historic myths that were created to explain it reveals the troubling role that early archaeologists played in diminishing, or even eradicating, the achievements of pre-Columbian civilizations on the North American continent, just as the U.S. government was expanding westward by taking control of Native American lands.

The city of Cahokia is one of many large earthen mound complexes that dot the landscapes of the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys and across the Southeast. Despite the preponderance of archaeological evidence that these mound complexes were the work of sophisticated Native American civilizations, this rich history was obscured by the Myth of the Mound Builders, a narrative that arose ostensibly to explain the existence of the mounds. Examining both the history of Cahokia and the historic myths that were created to explain it reveals the troubling role that early archaeologists played in diminishing, or even eradicating, the achievements of pre-Columbian civilizations on the North American continent, just as the U.S. government was expanding westward by taking control of Native American lands.

Today it’s difficult to grasp the size and complexity of Cahokia, composed of about 190 mounds in platform, ridge-top, and circular shapes aligned to a planned city grid oriented five degrees east of north. This alignment, according to Tim Pauketat, professor of anthropology at the University of Illinois, is tied to the summer solstice sunrise and the southern maximum moonrise, orientating Cahokia to the movement of both the sun and the moon. Neighborhood houses, causeways, plazas, and mounds were intentionally aligned to this city grid. Imagine yourself walking out from Cahokia’s downtown; on your journey you would encounter neighborhoods of rectangular, semi-subterranean houses, central hearth fires, storage pits, and smaller community plazas interspersed with ritual and public buildings. We know Cahokia’s population was diverse, with people moving to this city from across the midcontinent, likely speaking different dialects and bringing with them some of their old ways of life.

The largest mound at Cahokia was Monks Mound, a four-terraced platform mound about 100 feet high that served as the city’s central point. Atop its summit sat one of the largest rectangular buildings ever constructed at Cahokia; it likely served as a ritual space.

In front of Monks Mound was a large, open plaza that held a chunk yard to play the popular sport of chunkey. This game, watched by thousands of spectators, was played by two large groups who would run across the plaza lobbing spears at a rolling stone disk. The goal of the game was to land their spear at the point where the disk would stop rolling. In addition to the chunk yard, upright marker posts and additional platform mounds were situated along the plaza edges. Ridge-top burial mounds were placed along Cahokia’s central organizing grid, marked by the Rattlesnake Causeway, and along the city limits.

Cahokia was built rapidly, with thousands of people coming together to participate in its construction. As far as archaeologists know, there was no forced labor used to build these mounds; instead, people came together for big feasts and gatherings that celebrated the construction of the mounds.

Cahokia was built rapidly, with thousands of people coming together to participate in its construction. As far as archaeologists know, there was no forced labor used to build these mounds; instead, people came together for big feasts and gatherings that celebrated the construction of the mounds.

The splendor of the mounds was visible to the first white people who described them. But they thought that the American Indian known to early white settlers could not have built any of the great earthworks that dotted the mid-continent. So the question then became: Who built the mounds?

Early archaeologists working to answer the question of who built the mounds attributed them to the Toltecs, Vikings, Welshmen, Hindus, and many others. It seemed that any group—other than the American Indian—could serve as the likely architects of the great earthworks. The impact of this narrative led to some of early America’s most rigorous archaeology, as the quest to determine where these mounds came from became salacious conversation pieces for America’s middle and upper classes. The Ohio earthworks, such as Newark Earthworks, a National Historic Landmark located just outside Newark, OH, for example, were thought by John Fitch (builder of America’s first steam-powered boat in 1785) to be military-style fortifications. This contributed to the notion that, prior to the Native American, highly skilled warriors of unknown origin had populated the North American continent.

This was particularly salient in the Midwest and Southeast, where earthen mounds from the Archaic, Hopewell, and Mississippian time periods crisscross the midcontinent. These landscapes and the mounds built upon them quickly became places of fantasy, where speculation as to their origins rose from the grassy prairies and vast floodplains, just like the mounds themselves. According to Gordon Sayre (The Mound Builders and the Imagination of American Antiquity in Jefferson, Bartram, and Chateaubriand), the tales of the origins of the mounds were often based in a “fascination with antiquity and architecture,” as “ruins of a distant past,” or as “natural” manifestations of the landscape.

When William Bartram and others recorded local Native American narratives of the mounds, they seemingly corroborated these mythical origins of the mounds. According to Bartram’s early journals (Travels, originally published in 1791) the Creek and the Cherokee who lived around mounds attributed their construction to “the ancients, many ages prior to their arrival and possessing of this country.” Bartram’s account of Creek and Cherokee histories led to the view that these Native Americans were colonizers, just like Euro-Americans. This served as one more way to justify the removal of Native Americans from their ancestral lands: If Native Americans were early colonizers, too, the logic went, then white Americans had just as much right to the land as indigenous peoples.

When William Bartram and others recorded local Native American narratives of the mounds, they seemingly corroborated these mythical origins of the mounds. According to Bartram’s early journals (Travels, originally published in 1791) the Creek and the Cherokee who lived around mounds attributed their construction to “the ancients, many ages prior to their arrival and possessing of this country.” Bartram’s account of Creek and Cherokee histories led to the view that these Native Americans were colonizers, just like Euro-Americans. This served as one more way to justify the removal of Native Americans from their ancestral lands: If Native Americans were early colonizers, too, the logic went, then white Americans had just as much right to the land as indigenous peoples.

The creation of the Myth of the Mounds parallels early American expansionist practices like the state-sanctioned removal of Native peoples from their ancestral lands to make way for the movement of “new” Americans into the Western “frontier.” Part of this forced removal included the erasure of Native American ties to their cultural landscapes.

In the 19th century, evolutionary theory began to take hold of the interpretations of the past, as archaeological research moved away from the armchair and into the realm of scientific inquiry. Within this frame of reference, antiquarians and early archaeologists, as described by Bruce Trigger, attempted to demonstrate that the New World, like the Old World, “could boast indigenous cultural achievements rivaling those of Europe.” Discoveries of ancient stone cities in Central America and Mexico served as the catalyst for this quest, recognizing New World societies as comparable culturally and technologically to those of Europe.

But this perspective collided with Lewis Henry Morgan’s 1881 text Houses and House-life of the American Aborigines. Morgan, an anthropologist and social theorist, argued that Mesoamerican societies (such as the Maya and Aztec) exemplified the evolutionary category of “Middle Barbarism”—the highest stage of cultural and technological evolution to be achieved by any indigenous group in the Americas. By contrast, Morgan said that Native Americans located in the growing territories of the new United States were  quintessential examples of “Stone Age” cultures—unprogressive and static communities incapable of technological or cultural advancement. These ideologies framed the archaeological research of the time.

quintessential examples of “Stone Age” cultures—unprogressive and static communities incapable of technological or cultural advancement. These ideologies framed the archaeological research of the time.

In juxtaposition to this evolutionary model there was unease about the “Vanishing Indian,” a myth-history of the 18th and 19th centuries that depicted Native Americans as a vanishing race incapable of adapting to the new American civilization. The sentimentalized ideal of the Vanishing Indian—who were seen as noble but ultimately doomed to be vanquished by a superior white civilization—held that these “vanishing” people, their customs, beliefs, and practices, must be documented for posterity. Thomas Jefferson was one of the first to excavate into a Native American burial mound, citing the disappearance of the “noble” Indians—caused by violence and the corruption of the encroaching white civilization—as the need for these excavations. Enlightenment-inspired scholars and some of America’s Founders viewed Indians as the first Americans, to be used as models by the new republic in the creation of its own legacy and national identity.

During the last 100 years, extensive archaeological research has changed our understanding of the mounds. They are no longer viewed as isolated monuments created by a mysterious race. Instead, the mounds of North America have been proven to be constructions by Native American peoples for a variety of purposes. Today, some tribes, like the Mississippi Band of Choctaw, view these mounds as central places tying their communities to their ancestral lands. Similar to other ancient cities throughout the world, Native North Americans venerate their ties to history through the places they built.

Editor’s Note: The original story stated that William Bartram’s Travels was published in 1928, but these early journals were actually published in 1791.