Joseph Smith during his lifetime more than likely knew about many of the Indian Chiefs below, who were from the same vicinity as him. Some lived at the same time as Joseph Smith and he may have also spent time with many of them. I share some unique articles below that you may find interesting in understanding young Joseph and his opportunities to learn from Native Americans.

Joseph Smith during his lifetime more than likely knew about many of the Indian Chiefs below, who were from the same vicinity as him. Some lived at the same time as Joseph Smith and he may have also spent time with many of them. I share some unique articles below that you may find interesting in understanding young Joseph and his opportunities to learn from Native Americans.

“Use of Ganargua Creek dates back to pre-colonial times. It was a primary stopover point for the Iroquois on their trade routes. Mormonism founder Joseph Smith also had an interest in the creek after hearing a speech from Seneca Indian Chief Red Jacket at Palmyra in 1822. Before the Erie Canal was constructed in 1817, Ganargua Creek originally met the Canandaigua Outlet in Lyons to form the Clyde River.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ganargua_Creek

“The Iroquois Confederacy had been a functioning democracy for centuries by Benjamin Franklin’s day. Sometime between 1000 and 1450, the Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, and Seneca Nations came together to become the Iroquois Confederacy, and in the early 18th century they were joined by the Tuscaroras. Referred to as the Six Nations by the English, and the Iroquois by the French, the Confederacy called themselves the Haudenosaunee, or People Building a Long House.” By Cynthia Feathers and Susan Feathers www.upenn.edu/gazette/0107/gaz09.html

“Contrary, then, to widespread assumptions during Joseph Smith’s lifetime that the Onondaga migrated to the New York region, it becomes clear that they originated here as a small, narrowly localized amalgamation of a few villages near Onondaga Lake, during the century before Columbus’ discovery of America” Beauchamp’s Aboriginal Place Names of New York;

“How America Was Discovered is a story told by Handsome Lake (Seneca Prophet), and documented by Arthur C. Parker, about a young minister who meets the one he perceives to be the Lord, who then asks him to go to a new land and bring with him cards, money, a fiddle, whiskey, and blood corruption. In return the young minister will become rich. The young minister sought out Christopher Columbus, and with the help of his crew, traveled to the Americas. They turned back to report what they had seen, which caused an immigration of people from Europe to the Americas. Along with the people came the five things that aided in destroying the natives. The end reveals that the “Lord” in the gold castle was actually the devil, and that even he knew what he had caused was wrong.” Rudes, B. Tuscarora English Dictionary Toronto.

“On the one hand, there are parallels between Handsome Lake’s teachings and Book of Mormon, economic and social interactions between Iroquois and white settlers at the time were still extensive during the early decades of the 19th century, and Lucy Mack Smith wrote that Joseph talked about Indians “as if he had spent his whole life among them.” Lucy Mack Smith, Biographical Sketches of Joseph Smith, the Prophet, and His Progenitors for Many Generations (Liverpool: S.W. Richards, 1853. “Joseph Smith was interested in the people who lived around him. Young Joseph was a member of the juvenile debating club in Palmyra during 1822 when Red Jacket, arguably the most widely-known Seneca of this period, delivered a speech in town. Joseph also liked to hang out on Ganargua Creek (Mud Creek) in the area where Iroquois travelers camped. He had interest and access.” Joseph Smith and the Code of Handsome Lake Lori Taylor, Ph.D.

The Onondaga Nation at the great white pine tree in Syracuse NY on the shores of Onondaga Lake is where the message of peace was planted, and the hatchets were buried according to many researchers. Similarly, the Lamanites , “…buried the weapons of war, for peace.” (“a peacemaker crossed Onondaga Lake in a stone canoe, how he convinced warring nations to bury their weapons beneath a tree of peace.”) Sean Kirst Syracuse.com (Compare Alma 24:19)

“The Onondagas: These have special interest… this warrior, Zelph, was an Onondaga, as well as a “white” Lamanite, and that the Onondagas (of New York), consequently must be of Lamanite lineage.” J.M. Sjodahl, An Introduction to the Study of the Book of Mormon

INDIAN SPEECH, Delivered before a Gentleman Missionary, from Massachusetts, by a Chief, commonly called by the white people RED JACKET. His Indian name is SAGU-Y A-WHAT-HATH, which being interpreted, is KEEPER-AWAKE.

In the summer of 1805, a number of the principal chiefs and warriors of the Six Nations of Indians, principally Senecas, assembled at Buffaloe Creek, in the State of New-York, at the particular request of a gentleman missionary, (Rev. Mr. Cram,) from the State of Massachusetts. The missionary being furnished with an interpreter, and accompanied by the agent of the United States, for Indian Affairs, met the Indians in council, and had a talk with them; when their Chief delivered the following answer:

Friend & Brother. —It was the will of the Great Spirit that we should meet this day. He orders all things and has given as a fine day for our council. He has taken his garment from before the sun, and caused it to shine with brightness upon us. Our eyes are opened, that we see clearly; our ears are unstopped, that we have been able to hear distinctly the words you have spoken. For all these favors we thank the Great Spirit, and HIM only.

Brother. This council fire was kindled by you. It was at your request that we came together at this time. We have listened with attention to what you have said. You requested us to speak our minds freely. This gives us great joy; for we now consider that we stand upright before you, and can speak what we think. All have heard your voice, and all speak to you as one man. Our minds are agreed.

Brother. You say you want an answer to your talk before you leave this place. It is right you should have one, as you are at a great distance from home, and we do not wish to detain you. But we will first look back a little, and tell you what our fathers have told us, and what we have heard from the white people.

Brother. Listen to what we say. There was a time when our forefathers owned this great island. Their feats extended from the rising to the setting of the sun. The Great Spirit had made it for the use of the Indians. He had created the buffaloe, the deer, and other animals for food. He had made the bear and the beaver. Their skins served us for clothing. He had scattered them over the country, and taught us how to take them. He had caused the earth to produce corn for bread. All this He had done for his red children because he loved them. If we had some disputes about our hunting ground, they were generally settled without the shedding of much blood. But an evil day came upon us. Your fore-fathers crossed the great water and landed upon this island. Their numbers were small. They found friends, not enemies. They told us they had fled from their own country for fear of wicked men, and had come here to enjoy their religion. They asked for a small seat. We took pity on them, we granted their request, and they sat down amongst us. We gave them corn and meat, they gave us poison [alluding, it is supposed to ardent spirits] in return.

The white people had now found our country. Tidings were carried back and more came amongst us. Yet we did not fear them. We took them to be friends. They called us brothers. We believed them, and gave them a larger seat. At length their numbers had greatly increased. They wanted more land; they wanted our country. Our eyes were opened and our minds became uneasy. Wars took place. Indians were hired to fight against Indians, and many of our people were destroyed. They also brought strong liquors amongst us. It was strong and powerful and has slain thousands.

Brother. Our seats were once large and yours were small. You have now become a great people, and we have scarcely a place left to spread our blankets. You have got our country, but are not satisfied; you want to force your religion upon us.

Brother. Continue to listen.

You say you are sent to instruct us how to worship the Great Spirit agreeably to his mind, and, if we do not take hold of the religion which you white people teach, we shall be unhappy hereafter. You say that you are right and we are lost. How do we know this to be true? We understand that your religion is written in a book. If it was intended for us as well as you, why has not the Great Spirit given to us, and not only to us, but to our forefathers, the knowledge of that book, with the means of understanding it rightly? We only know what you tell us about it. How shall we know when to believe, being so often deceived by the white people.

Brother. You say there is but one way to worship and serve the Great Spirit. If there is but one religion, why do you white people differ so much about it? Why not all agreed, as you can all read the book?

Brother. We do not understand these things. We are told that your religion was given to your forefathers, and has been handed down from father to son. We also have a religion, which was given to our forefathers, and has been handed down to us their children. We worship in that way. It teaches us to be thankful for all the favors we receive: to love each other, and to be united. We never quarrel about religion.

Brother. The Great Spirit has made us all, but he has made a great difference between his white and red children. He has given us different complexions and different customs. To you he has given the arts. To these he has not opened our eyes. We know these things to be true. Since he has made so great a difference between us in other things; why may we not conclude that he has given us a different religion according to our understanding? The Great Spirit does right. He knows what is best for his children; we are satisfied.

Brother. We do not wish to destroy your religion, or take it from you. We only want to enjoy our own.

Brother. We are told that you have been preaching to the white people in this place. These people are our neighbors. We will wait a little while and see what effect your preaching has upon them. If we find it does them good, makes them honest and less disposed to cheat Indians; we will then consider again what you have said.

Brother. You have now heard our answer to your talk, and this is all we have to say at present. As we are going to part, we will come and take you by the hand, and hope the Great Spirit will protect you on your journey, and return you safe to your friends.

As the Indians began to approach the missionary, he rose hastily from his seat and replied, that he could not take them by the hand, that there was no fellowship between the religion of God and the works of the devil.

It being afterwards suggested to the missionary that his reply to the Indians were rather indiscreet; he observed, that he supposed the ceremony of shaking hands would be received by them as a token that he assented to what they had said. Being otherwise informed, he said he was sorry for the expression.

NATHANIEL COVERLY, Printer, Milk St. Boston.

Early Mormon Lamanism, Forgotten Apocalyptic Visions, and the Indian Prophet

Early Mormon Lamanism, Forgotten Apocalyptic Visions, and the Indian Prophet

The year 1890 looms large in American history. It ranks up there with 1776, 1877, and 1945 as important dates that historians have used to organize our past. It also shapes collective memory. Mormons most readily associate 1890 with the Woodruff Manifesto and the ?official? end of polygamy. For Americans, and westerners more specifically, 1890 represents the end of the Frontier, the most American part of our history, to paraphrase Frederick Jackson Turner. According to C. Vann Woodward, the 1890s marked the hardening of segregation in the South.

1890 also marked the date of the last significant massacre of between 150 and 300 Oglala Lakota Indians (Sioux) at Wounded Knee, South Dakota. As the last major altercation between a Native group and the U.S. military, Wounded Knee has taken on great significance in Western and Native histories, marking the symbolic date of the last time that Native peoples had the potential to rise up militarily to define their own destinies. As Philip Deloria has noted, ?Some people?especially white Americans?dated the end of the old days to 1890, when U.S. soldiers had surrounded and slaughtered Big Foot’s band at Wounded Knee Creek. . . . Wounded Knee seemed to mark a. . .division across time. It split old days apart from new days (even as memory and shared culture stitched them together again).?[1] For white America,

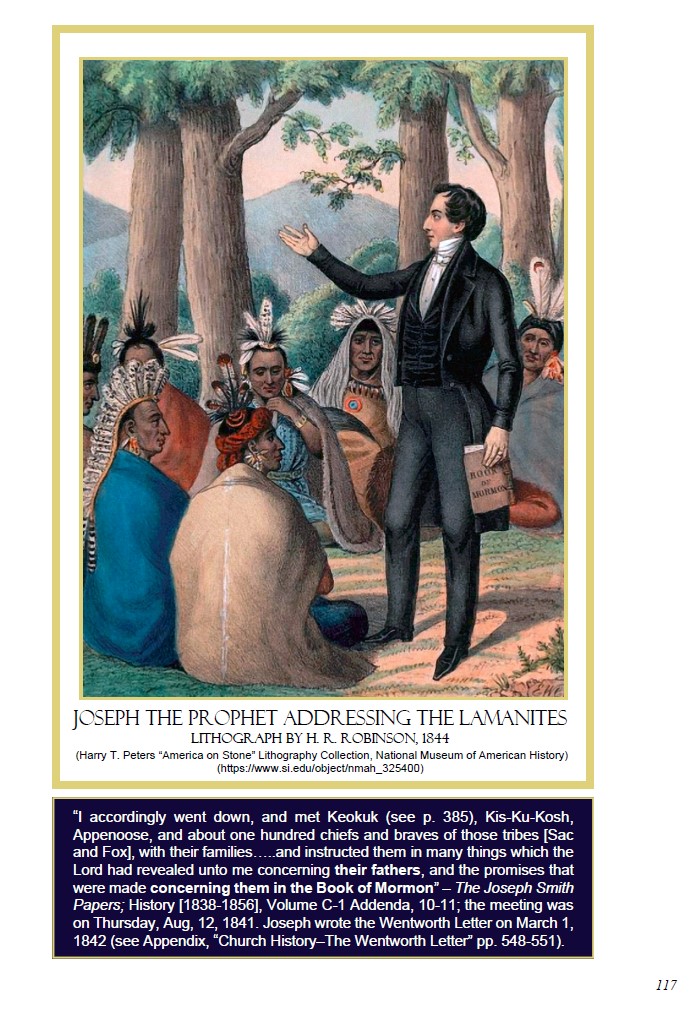

Wounded Knee marked the end of the ?Indian Wars? of the late nineteenth-century, the last of the ?heroic yet doomed? military struggles over the fate of the continent. Wounded Knee also had significant consequences for what might be called ?Lamanism,? or the cultural production of Lamanites among white Latter-day Saints. As John-Charles Duffy suggests, the massacre ended ?armed resistance to the U.S. government. . . .[and] Indians’ submission to the reservation system dulled apocalyptic expectations about Lamanites violently reclaiming their promised land.?[2] In truth, it is doubtful that most white Mormons today, or even most Mormon historians for that matter, recognize the full significance of Lamanites/Native Americans in early Mormon history.[3] When The Book of Mormon appeared in 1830, it was a radical document, one that envisioned the eradication of much of white America by Native Americans and the absorption of a small group of converted Gentiles into the chosen remnant of Jacob (see especially 3 Nephi 21). Much of Joseph Smith’s Zion project centered around the promise of the large-scale conversion of Lamanites and rumors circulated from the 1830s through the 1890s of a white Mormon/Native American alliance that would wipe out white America. Parley P. Pratt, in his highly influential Voice of Warning, addressed Native America in saying that the very places of their [that is, white Americans] dwellings will become desolate except such of them as are gathered and numbered with you; and you will exist in peace, upon the face of this land, from generation to generation. And your children will only know, that the Gentiles once conquered this country, and became a great nation here, as they read it in history; as a thing long since passed away, and remembrance of it almost gone from the earth.[4]

Perhaps due to the rampant rumors of the white Mormon-Native alliance, Pratt deleted this passage from subsequent editions. Ironically, with the possibility of such Indian violence existing only in memory or distant millennialism after 1890, it has been white Mormons who have largely forgotten the violent Lamanism of the early church.

White Mormons have also forgotten that some early Saints looked for the Lord to raise up a great Indian prophet. In late 1830, Ohio newspaperman Eber D. Howe noted that Oliver Cowdery and his companions continued ?on their mission to the Indians (or Lamanites, as they term them) in the ‘far west,’ where they say a Prophet is to be raised up, in whom the tribes will believe.?[5] This is intriguing. Unfortunately, surviving evidence has not been located to flesh out what else Cowdery, JS, or others thought of this Indian prophet. However, when Orson Pratt prepared annotations for the 1879 edition of the Book of Mormon, his footnote for 2 Nephi 3:24, And there shall rise up one mighty among them, who shall do much good, both in word and deed, being an instrument in the hands of God, with exeeding faith, to work mighty wonders, and do that which is great in the sight of God, unto the bringing to pass much restoration unto the house of Israel, and unto the seed of thy brethren.

Pratt noted that the one to be risen up would be ?an Indian prophet.?[6] Howe’s use of the phrase ?to be raised up? suggests that Cowdery and others had this verse in mind when talking about this Indian prophet, although without more evidence, we can’t know for certain.

The missionaries visited the Wyandots (Hurons), the Delawares, the Catteraugus (Seneca Iroquois), and the Shawnees during this first Lamanite mission. While we do not know for sure why these groups were chosen for proselyting, Lori Taylor has noted that each of these Native nations claimed prophetic traditions. The Hurons spoke of Deganawidah, the Master of Things and the Peacemaker, a Huron prophet who taught the Iroquois Confederacy a new social order of cooperation. The Delawares followed Neolin, a prophet who encouraged his people to reject European ways in favor of the old ways, in order to gain favor with the Great Spirit. Neolin was associated with Pontiac and his war in 1763-1764. The Iroquois believed in Handsome Lake, a prophet who received heavenly visitations in 1799-1800 from four visitors who encouraged him and his people to embrace traditional practices and to observe the ceremonial cycle. He encouraged his people to give up alcohol, witchcraft, and other vices. And lastly, the Shawnees followed Tenskwatawa, brother of the famous Tecumseh, who taught that the Shawnee needed to reject white ways in order to push back white settlement. Tenskwatawa learned from Handsome Lake and taught some things that appears to be influenced by Christianity. Although it is unclear how much the early Mormons knew about these prophets or the Native peoples who claimed them, Taylor’s speculation that the missionaries proselyted the Wyandots, Delawares, Catteraugus, and Shawnees for this reason remains intriguing. Equally fascinating is Taylor’s analysis of a story told by some contemporary Iroquois that JS knew about Handsome Lake’s teachings (who was active in western New York until his death in 1815) and that the Book of Mormon was shaped by Handsome Lake’s ideas.[7] Whether there is any truth to such accounts awaits further investigation by ethnohistorians, but one thing is certain, the Book of Mormon and early white Mormon interpretations of it had more in common with the apocalyptic visions of Neolin, Tenskwatawa, and other Native prophets than with the views of most other white Americans of the nineteenth century.

_______

[1] Deloria, Indians in Unexpected Places, 15-16.

[2] Duffy, ?The Use of ‘Lamanite’ in Official LDS Discourse,? Journal of Mormon History 34, no. 1 (Winter 2008): 131.

[3] Walker, “?Seeking the ‘Remnant’: The Native American during the Joseph Smith Period,? Journal of Mormon History 19, no. 1 (1993): 1-33. Walker argues that historians have largely failed to recognize the centrality of Native Americans in early Mormonism. Mormon historians are not alone in marginalizing the importance of Native Americans when writing about nineteenth-century America. See Susan Scheckel’s The Insistence of the Indian: Race and Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century American Culture for a discussion of the centrality of Natives in nineteenth-century America and the tendency of twentieth-century historians to emphasize slavery as the central race question of the century. Much of the new New Indian History of the last two decades has recovered the power and agency of Native peoples in early American history. See Richard White, The Middle Ground, Alan Taylor, The Divided Ground, Ned Blackhawk, Violence Over the Land, and Pekka Hamalainan, The Comanche Empire, for some of the best examples of this new literature.

[4] As quoted in Underwood, The Millenarian World of Early Mormonism, 80.

[5] ?The Book of Mormon,? The Painesville Telegraph, 30 November 1830, 3.

[6] Thanks to Robin Jensen, the 2004 Joseph Smith Papers Student Researcher of the Year, for checking the reference for me.

[7] Taylor, ?Telling Stories About Mormons and Indians,? PhD. Diss, State University of New York at Buffalo, 2000, 141-60, 306-51. Taylor notes that Handsome Lake’s nephew, Red Jacket, spoke in Palmyra in 1822.

Native Americans and early Mormonism. Juvenile Instructor

Joseph Smith and the Code of Handsome Lake by Lori Taylor, Ph.D.

Lori Taylor has three degrees in American Studies: Ph.D. from the SUNY at Buffalo, M.A. from The George Washington University, and B.A. from Brigham Young University. Through all of those degrees, she chased down the ways people frame and reframe the cultural and historical tidbits from which they make deep meaning. The joy in historiography for Lori is the story that makes THEN interesting NOW.

In 1994, sitting in a Western-themed lodge in Billings, Montana, a friend and colleague told me a story that I spent the next several years hunting down. I’m trained as a folklorist and oral historian, so the play of story, memory, and forgetting influence my understanding of histories. Whether the concept of “truth” plays any part in an exploration of this story, I’m not so sure. If the concept of “fact” is slippery for historians, “truth” is even more so.

“You’re a Mormon?” Nicholas said to me. “Oh, boy, do I have a good story to tell you.”

“You’re a Mormon?” Nicholas said to me. “Oh, boy, do I have a good story to tell you.”

He spent more than an hour telling me about a sundance at Turtle Mountain in 1987 when dancers were talking as they prepared for the dance. It was here that he first heard the story he told me.

“Hey, you guys ever hear the story of how the Mormons came to be?” Wabanimkee had asked Nicholas and the other dancers. “The real story?”[1]

He told them about hard times in western New York after the War of 1812. The Senecas’ transition from their pre-white-settlement lives to the new reality after two generations was not going well. Iroquois have long been farmers, but crops had failed during the year of no summer in 1816. The local Indian agent wrote, “The situation of the Indians is truly deplorable.”[2]

During this period of transition and difficulty, the story goes, a young Joseph Smith worked as a field hand. He met Seneca field hands who were not like the other Senecas who were “into alcohol and debauchery and stuff.” He asked them why they were “so solid, so stable, so strong. And they say, well, they were followers of Handsome Lake.” Who was Handsome Lake? They told him.

Handsome Lake spent the last 15 years of his life, from 1800 to 1815, encouraging his people to turn away from alcohol, gambling, promiscuity, witchcraft, and the worst excesses that came with the settlers. He asked them to follow a code and a ceremonial cycle that maintained their Haudenosaunee identity while also embracing elements white Christian values. He preached of the need to adjust in order to survive. It wasn’t until 1826 that the women Faithkeepers of Tonawanda asked Handsome Lake’s grandson to recall the words of the teacher.[3] From these recollections, they created the Code of Handsome Lake, which has since evolved into the Gaiwiio (Good Word), the syncretic American religion practiced today as the longhouse religion of the Haudenosaunee. For most Iroquois, Handsome Lake is a prophet.

The Seneca field hands told Joseph Smith that Handsome Lake “found a way of blending” the best of Iroquois traditions and the best of Christian traditions “because his vision told him that they only way his people were going to survive is if they held on to the root, the main root of who they were throughout time that gave them a sense of identity and strength and consistency of heritage.” They had to incorporate the new into the old “in order for them to get along in this new society that was forming.”

Hearing the story of mixing two world views into a New World view, Joseph Smith said, “this is just what the white people need because they’re just as pitiful as the Indians are. And, because it’s a new world for everybody, what the white people need to do is to take the best of their Christian heritage and traditions and stuff that come out of their European ways and mix it with the indigenous ways of the people who have lived on this land for a long time.”

“And, so what he decided, what was really needed was an equivalent of Handsome Lake’s Gaiwiio, but for the white people, maybe with a little more Christian emphasis.”

What about all of the books and gold, the dancers asked the storyteller. The Senecas helped Joseph Smith, he said. “We’ll be better, us Indians will be better off if you white people do just like we did to get along here in this new world. We’ll be better off if you folks can understand us a little bit more by taking in some of our world view, too. So, we will help you. We will help you bring this new word. We will help you bring the Word to your own people.”

The teller of the story goes on to outline melting of the gold paid Tonawanda Senecas by the British for their help during the War of 1812 into tablets like Moses’ commandments, a story that bears no resemblance to reports of thin, brass plates found in construction of the Erie Canal during that generation. They told their stories in their own writing, taught him how to read it, then told him how he would make the discovery of his golden book a media event.

The story ends, and the sundance went on. Nicholas told me the story, and he told a few others, just as Wabanimkee had told a few others before.

In the years I spent asking whether such events could be possible let alone plausible—years I spent in graduate school in western New York with Haudenosaunee teachers, students, and friends—I heard a few much shorter versions of the story.

Among the questions I asked during my research was, what other comparisons have been made by those familiar with both the Iroquois longhouse and Mormonism? Edmund Wilson, on a tour of the Six Nations for the New Yorker in the 1950s, visited Philip Cook, Mohawk of Akwesasne. Cook was a convert to the LDS church. He told Wilson that he wondered whether Joseph Smith might have been influenced by Handsome Lake through Senecas in western New York, but “he concluded that no white man at the time could ever have had access to their ceremonies or understood what was said if he had.”[4]

Tracing the lines of acquaintances of all the people I know who know this story (at least, those who told me they know this story),[5] I find that one man knew them all or knew who told them. In another of Edmund Wilson’s articles for the New Yorker, he wrote of Wallace “Mad Bear” Anderson, in 1958 a dynamic man of 31 years old. Mad Bear become one of those elders who for young people in the 1960s and 1970s imparted Indian wisdom and stories. He also, in his extensive travels, made connections with indigenous peoples around the world and worked to bring them together. He spread Iroquois stories and his contemporary interpretations far and wide as a merchant seaman then as a travelling elder.

Mad Bear Anderson is the trickster figure in the story of Handsome Lake followers and Joseph Smith—possibly a source, possibly just a very strong teller of the tale.

Could these events have happened?

On the one hand, there are parallels between Handsome Lake’s teachings and Book of Mormon, economic and social interactions between Iroquois and white settlers at the time were still extensive during the early decades of the 19th century, and Lucy Mack Smith wrote that Joseph talked about Indians “as if he had spent his whole life among them.”[6] Joseph Smith was interested in the people who lived around him. Young Joseph was a member of the juvenile debating club in Palmyra during 1822 when Red Jacket, arguably the most widely-known Seneca of this period, delivered a speech in town. Joseph also liked to hang out on Ganargua Creek (Mud Creek) in the area where Iroquois travelers camped. He had interest and access.

On the other hand, melting down gold for thick tablets seems unlikely for quite a few reasons, including economic reality and cultural skill sets, and a coordinated cross-cultural media event is more of our day than of the 19th century. Even if such an event as described in the story actually happened in time, it is unlikely there would be any historically useful trace beyond memory through story.

Is the story possible? Sure. Is it plausible? Probably not, at least not in the specifics. After 200 years, a story can stretch to meet a lot of different needs. I’ve frequently heard people say after hearing the story, “I always wondered about that.” This story makes connections between peoples, connecting a few dots of curiosity. That may be the need it meets. Then again, it may bring up more questions than it claims to answer as it sparks an interest in what happened hundreds of years ago between early Mormons and their Haudenosaunee neighbors.

A generation ago, after scholars went through New York, turned it upside down and shook it out, someone asked if there is “anything new to be found in the history of the Church in New York.”[7]

Scholars have looked for influences on Mormonism in Puritan roots, evangelical revivals, hermetic traditions, folk magic, and in various social movements. Given the fact that Joseph Smith lived in Iroquoia—New York, Ontario, and beyond—we can include those historical sources for another potential area of influence. There is plenty “anything new” in Mormon history where it meets the parallel space of Indian Country. I’m confident more areas of influence will be added to the list in time as well.

Of course there is an endless new history to be written. We look in different places. We find different traces of the past. We ask different questions as we ourselves change. And, we rewrite histories we thought we knew when they no longer answer the questions we ask about our past. If history weren’t so fluid, there wouldn’t be much point in our discussing it here.

NOTES

The story and the questions come from my PhD dissertation, Telling Stories about Mormons and Indians (State University of New York at Buffalo, 2000).

[1] Nicholas C. P. Vrooman, “Handsome Lake, Joseph Smith, and the Word,” recorded 7 November 1994. For clarity, I’ve made my paraphrase and quotation of the story italics.

[2] Erastus Granger to Acting Secretary of War, George Graham, 20 January 1817. In Charles M. Snyder, ed., Red and White on the New York Frontier: A Struggle for Survival. Insights from the Papers of Erastus Granger, Indian Agent, 1807-1819 (Harrison, New York: Harbor Hill Books, 1978): 85.

[3] Elisabeth Tooker, “Iroquois Since 1820,” in Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 15, Northeast, ed. Bruce G. Trigger (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978): 452. There were others who contributed to the codification of the teachings of Handsome Lake as well.

[4] The New Yorker articles were published as Edmund Wilson, Apologies to the Iroquois (1959, 1960; Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1991): 123.

[5] Even as a colleague read over this post before I sent it, he said, “Now I understand better what my grandfather said to me about Seneca gold.” People I’ve known for years sometimes come up with pieces around the edges of this story.

[6] Lucy Mack Smith, Biographical Sketches of Joseph Smith, the Prophet, and His Progenitors for Many Generations (Liverpool: S.W. Richards, 1853): 85. If she told her stories in chronological order, the dates of these recitals would be 1823 or 1824.

[7] Chad Flake, review of The Restoration Movement: Essays in Mormon History, eds. F. Mark McKiernan, Alma R. Blair, Paul M. Edwards, BYU Studies 15/3 (Spring 1975): 373.

New theory connects a Native American prophet with Joseph Smith and the Book of Mormon

by Jana Riess on Religion News Service

“Peter Manseau published a wonderfully engaging book on American religious history. One Nation, Under Gods is chock-full of “Aha!” moments, but for purposes of this blog I wanted to talk with Peter about his chapter on early Mormonism’s interplay with Native Americans.

In particular, I was intrigued by a theory about the origins of the Book of Mormon that I had not heard before. (As you can read below, Peter is eager to point out that he was not the first to make a connection between Joseph Smith and the Seneca prophet Handsome Lake, but it was certainly new to me.) — JKR

RNS: First off, you say in the book that Joseph Smith “came to look upon Native Americans not merely as an evangelical challenge but as a key to understanding the Christian scriptures . . . . Why did Smith alone see the New World as a missing piece in the story the Old World told about itself?” Great question. What do you think?

Peter Manseau: The biggest theological problem Europeans faced when they arrived in America was what to do with Native Americans, whose existence suggested God created a population that didn’t fit into their biblical worldview. This prompted questions: “Do they have souls?”, “Are they of the devil?” For Joseph Smith, it was “Are these people mentioned in the Bible after all?” If they were, it solved a theological puzzle.

RNS: So you see Joseph Smith as being interested in the Hebraic origins of Native Americans. What is the connection with Handsome Lake?

Manseau: Handsome Lake was of the Seneca people, the brother of a chief called Cornplanter, who became known in the late 18th century as someone who had welcomed the Quakers in his village. Handsome Lake meanwhile was known as a ne’er-do-well and a drunk. One winter, he became sick and it seemed like he was going to die. While he lay dying, he had a vision of several figures who came to him and told him to reform his life. They instructed him to write down the visions as a message that came to be known as the Code of Handsome Lake.

Handsome Lake’s vision blended Native American and Quaker religious ideas. It really took hold among the Seneca, the Iroquois. He became quite well known for it.

Handsome Lake’s revival might be considered the Native American outgrowth of the Second Great Awakening that began in the region. This of course is where we find Joseph Smith as well, who grows up very much interested in Native American culture and the lore that existed all around him. He, too, was interested in the general question: what do you do religiously with Native Americans as a people not accounted for in the original revelation? Whether through revelation or imagination, he proposed an alternate story that accounts for them.

What scholars now are beginning to do is investigate how Joseph Smith was influenced by Native American culture, and specifically by a movement such as Handsome Lake’s.

RNS: Interesting. You note in the book that Handsome Lake’s nephew lectured in Palmyra just one month before Smith claimed to have found the golden plates.

Manseau: Handsome Lake’s nephew was another Iroquois leader named Red Jacket. He presented his ideas — not quite the Code of Handsome Lake, but something similar — when he was in Palmyra lecturing very shortly before Joseph Smith claimed to have discovered this new scripture that incorporated Native Americans into biblical history.

RNS: Did Joseph attend that lecture?

Manseau: It’s likely. It seems that given who he was at the time — a teenage boy very interested in Native Americans — the arrival of this renowned chief would have been a big deal. It was publicized in the Palmyra Gazette and other newspapers.

RNS: How did you first learn about this connection?

Manseau: I came across an unpublished dissertation by Lori Taylor, who wrote about the idea of Handsome Lake having potential influence on Joseph Smith. I had seen it referenced on Juvenile Instructor.

RNS: Bottom line: Was Joseph Smith influenced by Handsome Lake, even indirectly, in writing the Book of Mormon?

Manseau: Maybe. But the other side of the coin that apologetics would offer is that the Book of Mormon, being an ancient text, had influenced Native Americans from generation to generation so that there was already a remnant of Book of Mormon truth in Seneca culture. Then it becomes a question of in which direction influence might have moved.” Jana Riess

Interesting Information:

When serving as Mission President to the Seminole Indians in Central Florida, Murray J. Rawson was teaching a group of the tribe about the Book of Mormon when he was interrupted by their Chief, saying: “We had a war long ago with a light skinned people around the Great Lakes. We conquered them but we had so much respect for their warrior chief that we buried him at the mouth of the Oswego River that is in New York State. We don’t discuss this very much because it is an embarrassment to us. President Rawson then asked why this is an embarrassment, and the Chief replied, “ Our history is written on metal plates and buried in a hill in New York, but we don’t know which hill!” (Talk given to missionaries in training at the MTC, Provo, Utah 1979, by President Murray J. Rawson).

“In 1837, Elder Parley P. Pratt, one of the early defenders of the church, wrote a work entitled, “A Voice of Warning,” which has been published in many different editions in Europe and America. In the edition of 1885, published at Lamoni, Iowa, page 82, there is a quotation from Mr. Boudinot, which reads as follows: Mr. Boudinot in his able work, remarks concerning their language: “Their language in its roots, idiom, and particular construction, appears to have the whole genius of the Hebrew; and what is very remarkable, and well worthy of serious attention, has most of the peculiarities of the language, especially those in which it differs from most other languages. There is a tradition related by an aged Indian of the Stockbridge Tribe, that their fathers were once in possession of a ‘Sacred Book’ which was handed down from generation to generation, and at last hid in the earth, since which time they have been under the feet of their enemies. But those oracles were to be restored to them again, and then they would triumph over their enemies and regain their. ancient country, together with their rights and privileges.” JOURNAL OF HISTORY APRIL, 1909 Published by Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

(Above) In 1844 A.D. a newspaper called the “Prophet” published to the world in 1844 this broadside page declared that the Stick of Joseph had been translated and published into English for the first time. Notice the quote at the bottom from the aged Indian.