The United States Government’s Relationship with Native Americans

A brief overview of relations between Native Americans and the United States Government.

The history of relations between Native Americans and the federal government of the United States has been fraught. To many Native Americans, the history of European settlement has been a history of wary welcoming, followed by opposition, defeat, near-extinction, and, now, a renaissance. To Europeans and Americans, it has included everything from treatment of Native American nations as equals (or near-equals) to assimilation to exile to near-genocide, often simultaneously…

Treaty-Making?

After the Revolutionary War, the United States maintained the British policy of treaty-making with the Native American tribes. In general, the treaties were to define the boundaries of Native American lands and to compensate for the taking of lands. Often, however, the treaties were not ratified by the Senate, and thus were not necessarily deemed enforceable by the U.S. government, leaving issues unresolved.

On occasion, the representatives of Native American tribes who signed the treaties were not necessarily authorized under tribal law to do so. For example, William McIntosh, chief of the Muskogee-Creek Nation, was assassinated for signing the Treaty of Indian Springs in violation of Creek law.

Treaty-making as a whole ended in 1871, when Congress ceased to recognize the tribes as entities capable of making treaties. The value of the treaties also came to be called into question when the Supreme Court decided, in 1903, Congress had full power over Native American affairs, and could override treaties. Many of the treaties made before then, however, remained in force at least to some extent, and the Supreme Court was occasionally asked to interpret them.

One notable treaty with ongoing repercussions is the Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868. Under that treaty, the United States pledged, among other things, that the Great Sioux [Lakota] Reservation, including the Black Hills, would be “set apart for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation” of the Lakota Nation.

Although neither side fully complied with the treaty’s terms, with the discovery of gold in the area, the United States sought to buy back the Black Hills. The Lakota rejected the offer, resulting in the Black Hills War (1876-1877), which included Custer’s Last Stand at the Battle of Little Bighorn (June 25-26, 1876).

Finally, in 1877, Congress went back on the original treaty and passed an act reclaiming the Black Hills. In 1923, the Lakota sued. Sixty years later, the Supreme Court determined the annulment was a “taking” under the Fifth Amendment and that the tribe was owed “just compensation” plus interest starting from 1877. The tribe has refused to accept payment, however, and is still seeking return of the land. As of 2018, the amount due appears to be around $1 billion.” National Geographic https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/united-states-governments-relationship-native-americans

Joseph Smith and Many Misled by our Government

HISTORY OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS

Period I History of Joseph Smith, the Prophet by Himself Volume II An Introduction and Notes by B. H. Roberts CHAPTER XXVI. OPENING OF THE YEAR 1836–THE AMERICAN INDIANS–SPECIAL COUNCIL MEETINGS IN KIRTLAND.

January 6, 1836

“Much has been said and done of late by the general government in relation to the Indians ( Lamanites) within the territorial limits of the United States. One of most important points in the faith of the Church of the Latter Day Saints, through the fullness of the everlasting Gospel, is the gathering of Israel (of whom the Lamanites constitute a part)—that happy time when Jacob shall go up to the house of the Lord, to worship Him in spirit and in truth, to live in holiness; when the Lord will restore his judges as at the first, and His counselors as at the beginning; when every man may sit under his own vine and fig tree, and there will be none to molest or make afraid; when He will turn to them a pure language, and the earth will be filled with sacred knowledge, as the waters cover the great deep; when it shall no longer be said, the Lord lives that brought up the children of Israel out of the land of Egypt, but the Lord lives that brought up the children of Israel from the land of the north, and from all the lands whither He has driven them. That day is one, all important to all men.

In view of its importance, together with all that the prophets have said about it before us, we feel like dropping a few ideas in connection with the official statements from the government concerning the Indians. In speaking of the gathering, we mean to be understood as speaking of it according to scripture, the gathering of the elect of the Lord out of every nation on earth, and bringing them to the place of the Lord of Hosts, when the city of righteousness shall be built, and where the people shall be of one heart and one mind, when the Savior comes; yea, where the people shall walk with God like Enoch, and be free from sin. The word of the Lord is precious; and when we read that the vail spread over all nations will be destroyed, and the pure in heart see God, and reign with Him a thousand years on earth, we want all honest men to have a chance together and build up a city of righteousness, where even upon the bells of the horses shall be written Holiness to the Lord. The Book of Mormon has made known who Israel is, upon this continent. And while we behold the government of the United States gathering the Indians, and locating them upon lands to be their own, how sweet it is to think that they may one day be gathered by the Gospel...” HISTORY OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS Period I History of Joseph Smith, the Prophet by Himself

Editors Note:

Unfortunately that “one day” is not in 2022 or previous to now. The Prophet Joseph Smith was hoping shortly during his time, that our government was gathering the Lamanites to help them and begin their gathering to Zion. Latter on Joseph Smith knew our government was driving them out of their homeland, which was a disgrace. Latter on in this same article, Joseph Smith said the following.

“The joy that we shall feel, in common with every honest American, and the joy that will eventually fill their bosoms on account of nationalizing the Indians, will be reward enough when it is shown that gathering them to themselves, and for themselves, to be associated with themselves, is a wise measure, and it reflects the highest honor upon our government. [Unfortunately there was very little honor among many in our government].

Joseph Smith continues, “May they all be gathered in peace, and form a happy union among themselves, to which thousands may shout, Esto perpetua. “Let it be eternal” HISTORY OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS Period I History of Joseph Smith, the Prophet by Himself Volume II An Introduction and Notes by B. H. Roberts

We have learned many things since:

- The Book of Mormon, which contained Lehi’s prophecies, was published in March, 1830. The infamous “Indian Removal Act” was passed by Congress on May 28, 1830.

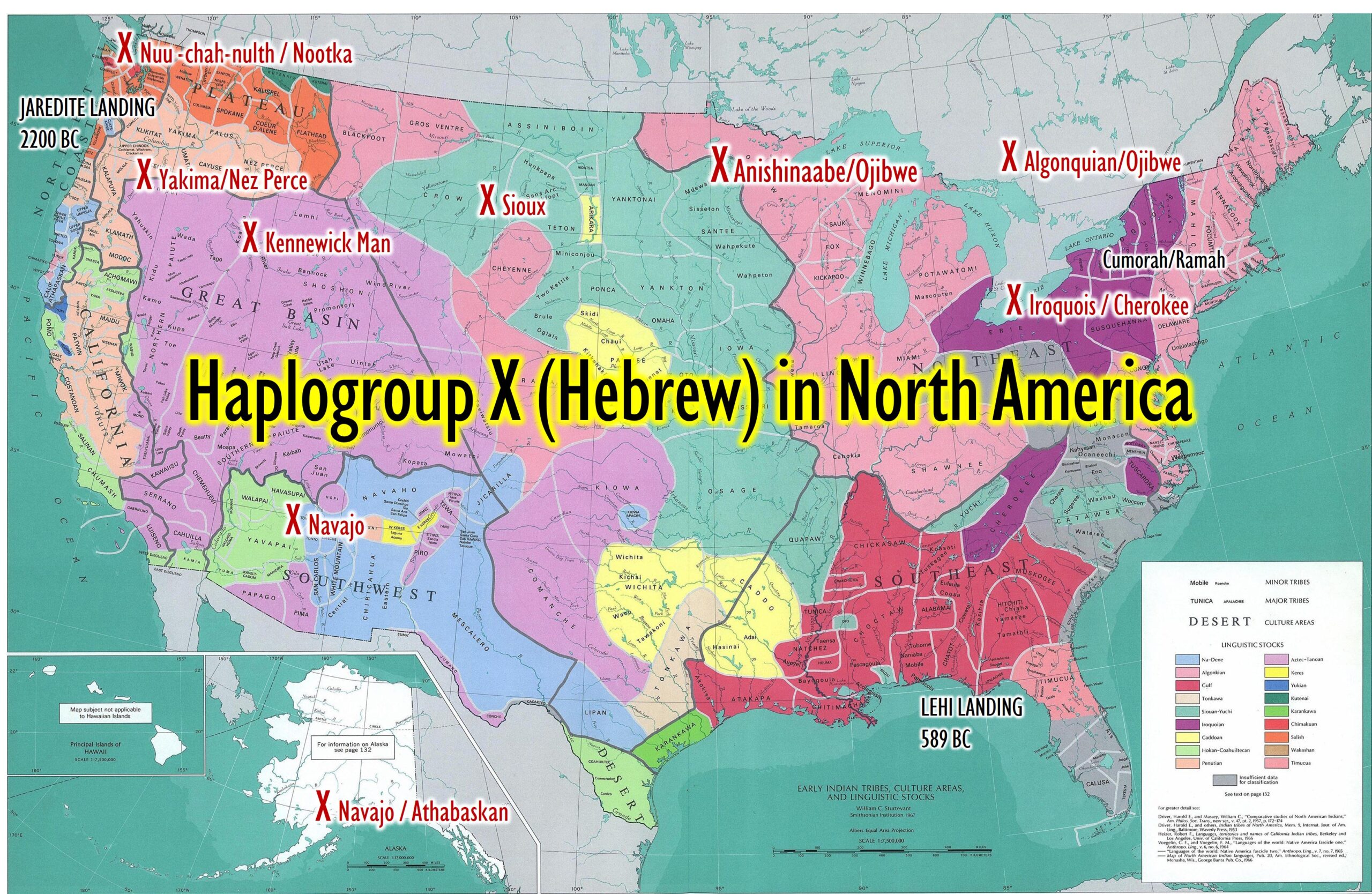

- In speaking to the Lamanites and others who are disobedient, the Book of Mormon said, “and he will take away from them the lands of their possessions, and he will cause them to be scattered and smitten.” 2 Nephi 1:10-11 [Mayan and Aztecs were not smitten and driven as they came from India. See my blog here].

- At the beginning of the 1830s, nearly 125,000 Native Americans lived on millions of acres of land in Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, North Carolina and Florida–land their ancestors had occupied and cultivated for generations. By the end of the decade, very few natives remained anywhere in the southeastern United States. Working on behalf of white settlers who wanted to grow cotton on the Indians’ land, the federal government forced them to leave their homelands and walk thousands of miles to a specially designated “Indian territory” across the Mississippi River. This difficult and sometimes deadly journey is known as the “Trail of Tears.”

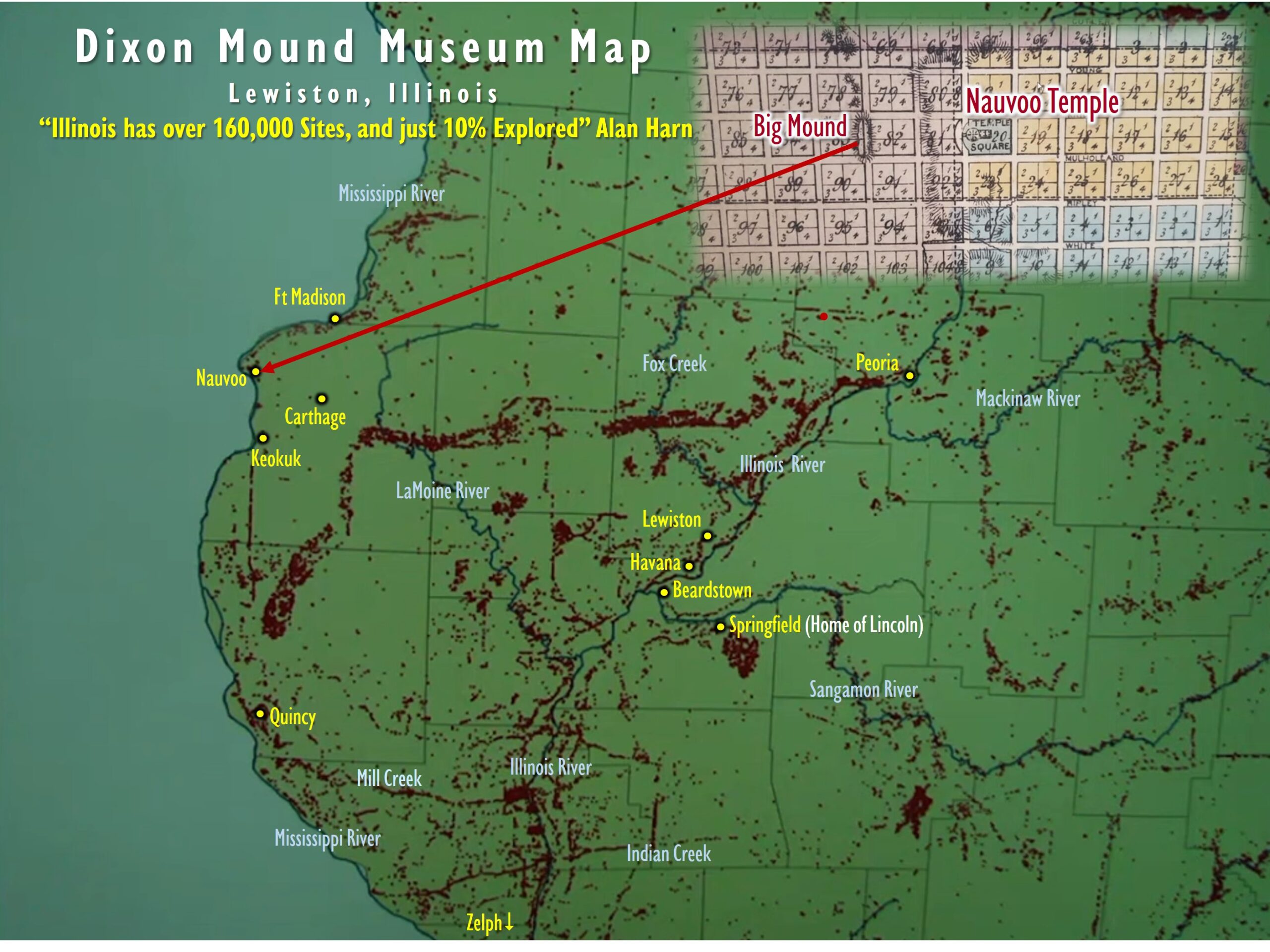

- Indian removal took place in the Northern states as well. In Illinois and Wisconsin, for example, the bloody Black Hawk War in 1832 opened to white settlement millions of acres of land that had belonged to the Sauk, Fox and other native nations.

Gather Israel

The Lord said, “Wherefore, this land is consecrated unto him whom he shall bring. And if it so be that they shall serve him according to the commandments which he hath given, it shall be a land of liberty unto them; wherefore, they shall never be brought down into captivity; if so, it shall be because of iniquity; for if iniquity shall abound cursed shall be the land for their sakes, but unto the righteous it shall be blessed forever.” 2 Nephi 1:7

Unfortunately the Lamanites were scattered for disobedience and some Americans sinned against God in the horrible things we did to them. We hope and pray this reuniting will return quickly as we Gather Israel. Much of the so-called “day of the blossoming as a rose” began in St George Temple Aug 29, 1877. See my blog here].

A Redemption for the Remnant Lamanites

“I would say to the Lamanites, if I could speak to them understandingly, that you are also a branch of the house of Israel, and chiefly of the house of Joseph, and your forefathers have fallen through the same examples of unbelief and sins, as have the Jews, and you, as their posterity, have wandered in sin and darkness for many generations; and you, like the Jews, have been driven and trampled under the foot of the Gentiles, and put to death through your wars with each other, and with the white man, until you are almost destroyed. But there is still a redemption and salvation for a remnant of you in the latter days.” History of His Life and Labors By Wilford Woodruff

Evil Against the Native American

Civilized Indians had been destroyed by barbarians who remained, and Indians-as-hostile-savages was a familiar motif in the Palmyra press during the period: Indians massacring anglos (Palmyra Register, 3 May 1820); white women falling captive to Indian savages (Wayne Sentinel, 17 Aug. 1824); children captured and raised by Indians (Palmyra Register, 3 July 1822); Indians fighting with each other (Palmyra Register, 19 July 1820). Even the Cherokees, (Iroquois) who had long been regarded as one of the most Christianized Indian nations, threatened to kill their own delegates to a peace conference upon their return from Washington because the tribe did not like the treaty the delegates had signed (Wayne Sentinel, 15 Aug. 1828).

Colonial attitudes toward Indians survived into the nineteenth century. There was the desire to get their lands, to kill or drive them [p.53] away. But there coexisted a guilty awareness that this was wrong and with this guilt a sense of obligation: convert and civilize them, or at least civilize them.” Joseph Smith’s Response to Skepticism Robert N. Hullinger

Editors Note: Read D&C 28, 30, and 32. Joseph Smith sent the first missionaries to the Lamanites (Native Americans of North America), who were the Cattaraugus (Iroquois) in Buffalo NY, the Wyandot, (Iroquois) in Ohio, and the Shawnee and Delaware (Algonquin) in Missouri. The Book of Mormon was to be shared with the Lamanites as it was written for them.

It is our duty to love the Hebrews and Lamanites and put in their hands the Book of Mormon. This is our duty.

Greatness With the Native American

Sagwitch The Corinne Scare

Chapter 4 1999 Sagwitch by Scott R. Christensen

“The white man is roaming all over my country and killing my game. Still I make no objection to his doing so, and all I want is to be let alone, with the privilege of making a small farm for the benefit of my people, and to be allowed to live on it in peace. I have not gone into the white man’s country and intruded on him, and I do not think it is fair for him to come into mine and drive me from my own lands without any cause, and I ask the government to take the matter in hand and reinstate me and mine on our own lands, that we may live there in peace and friendship with all men. “Sagwitch” August 31, 1875 Continued

As Brigham Young announced new missionary assignments at the Mormon Church’s general conference in April 1875, he signaled his resounding support of George Washington Hill’s work among the Indians by calling fifteen men for a season of work among the “Lamanites” of northern Utah—eight more men than he called to labor in all the rest of the United States and Canada.1 [Read more about George Washington’s work among the Native American’s in the following section called Native American Policy]. Young was willing to dedicate so much manpower to the Indian cause he anticipated a large return in Indian converts. He had been greatly impressed by the positive reports forwarded to his office in 1873 and 1874 concerning Native American converts to Mormonism. Now he wanted to see them transformed from nomadic hunters to sedentary and self-supporting farmers. As Mormonism’s prophet, he was undoubtedly anxious to support a movement that seemed to fulfill scriptural injunctions concerning the “redemption” of the remnants of the “House of Israel,” interpreted by the Mormons to be America’s indigenous peoples. Another practical benefit of the Lamanite Mission, if implemented successfully throughout the Great Basin, was much hoped for relief of white settlers from the temporal demands associated with Young’s “feed rather than fight” policies.

George Washington Hill was one of those called to labor among the Indians, and Young assigned him to head the mission. Hill’s first task was to find a suitable location for a continuation of the farming experiment begun at Franklin the summer before. The search took him north and west of Brigham City to an area about halfway between present-day Plymouth and Tremonton. In a report to President Young, Hill commented, “I went to look for a location[.] selected for permanent location a section of country lying betwen bear river and malad about twenty miles from corinne with good land and plenty of grass[.] water plenty but a heavy job to get it out.”2 The site had merit, including thousands of acres of fertile land needing only a plow and the diverted waters of the Malad River to make it productive. Young approved the location and asked the missionaries to gather there.

Sagwitch and his band of approximately seventy lodges returned from the Promontory region sometime in late winter. On February 22, 1875, Sagwitch and his wife, listed as Mogogah, but probably Beawoachee, along with fellow Shoshone Ohetocump and his wife, Minnie, entered the Mormon Endowment House located in the northwest corner of the temple block in Salt Lake City. They participated in sacred temple rituals and received the Mormon endowment. Afterward, Apostle Wilford Woodruff performed another ceremony that, according to Mormon belief, “sealed” each couple’s marriage in an everlasting union.3 Only a few Native Americans had received the Mormon endowment, and none had ever been sealed. Woodruff recorded the significant event in his journal: “This is not only the birthday of George Washington. But it was the day when the first Couple of Lamanites were together as man and wife for time & Eternity at the Alter in the Endowment House according to the Holy Priesthood in the last dispensation & fulness of times. Wilford Woodruff Sealed at the Altar two Couple of Lamanites. The first Couple was Indian Named Ohetocump But Baptized and Sealed by the name of James Laman. His wife Named Mine. 2d Couple Isiqwich [Sagwitch] & Mogogah.4“

Read my blog on Chief Sagwitch Here

Native American Policy by Richard Harless

George Mason University

“Near the beginning of his first term as President, George Washington declared that a just Indian policy was one of his highest priorities, explaining that “The Government of the United States are determined that their Administration of Indian Affairs shall be directed entirely by the great principles of Justice and humanity.”1 The Washington administration’s initial policy toward Native Americans was enunciated in June of 1789. Secretary of War Henry Knox explained that the Continental Congress had needlessly provoked Native Americans following the Revolution by insisting on American possession of all territory east of the Mississippi River. Congress had previously argued that by supporting the British during the war Native Americans had forfeited any claim to territory on the western frontier of American settlement. However, this perspective ignored the fact that only a portion of tribes had actually supported the British.

In 1787, the Confederation Congress enacted the Northwest Ordinance, opening the Ohio Valley to new American settlement. Members of the Western Lakes Confederacy reacted by utilizing armed resistance to protect their land. These events increased the urgency for Washington to develop a formal method for managing Indian affairs. In referring to the constitutional grant of treaty-making powers to the chief executive—with the “advice and consent” of the Senate—Washington declared that a similar practice should also apply to agreements with Native Americans. The Senate acceded to the President’s wishes and accepted treaties as the basis for conducting Indian relations.

In response, Congress proceeded to approve a treaty with seven northern tribes (the Shawnee, Miami, Ottawa, Chippewa, Iroquois, Sauk, and Fox). This agreement, however, lacked meaningful protection of tribal land. To the northern tribes this ineffectual treaty and the constant intrusion into their lands by droves of settlers meant that the American government had little control over its own citizens. Members of the northern tribes believed it was necessary to deploy force to prevent further incursions.

Washington’s desire to protect American citizens led to an American military response. In 1790 and 1791, Washington dispatched armies to confront native forces, and in both instances the Americans were soundly defeated. Responding to these two embarrassing setbacks, Congress authorized a five-thousand man regular army to quell resistance. Led by General “Mad Anthony” Wayne, the Legion inflicted a crushing defeat on the Indian confederation in the Summer of 1794. This decisive battle and the ensuing Treaty of Greenville brought a tentative peace to the northwest in 1795.

Simultaneously, as momentous events in the north unfolded, Washington also faced challenges from the four southern tribes. For the Cherokees and the more distant Choctaws and Chickasaws, Washington sought messages of assurance, friendship, and plans for trade. The formidable Creeks were the fourth southern tribe. Washington regarded the Creek with considerable apprehension because of their disagreement with the state of Georgia’s interpretation of three treaties that had been negotiated by that state during the 1780s. These treaties included significant cessions of land from the Creeks to Georgia that the tribe did not recognize.

The Creeks’ leader was Alexander McGillivray, a mixed-race chief who spoke fluent English and was a shrewd negotiator. Twenty-eight Creek chiefs led by McGillivray accepted Washington’s invitation to travel to New York in the summer of 1790 to negotiate a new treaty. The result was the Treaty of New York which restored to the Creeks some of the lands ceded in the treaties with Georgia, and provided generous annuities for the rest of the land. It also established a policy and process of assimilation called “civilization,” aiming to attach tribes to permanent land settlements. Under the policy tribal members would be given “useful domestic animals and implements of husbandry” to encourage them to become “herdsman and cultivators” instead of “remaining in a state as hunters.”2

In August 1790 the Creek chiefs formally approved the Treaty of New York. The Creek chiefs agreed to place themselves under the protection of the United States. In return the United States confirmed the sanctity of the Creek land lying within the boundaries defined by the treaty. However, the Treaty of New York failed to achieve its goals, as the federal government could not stem the relentless incursion of American settlers onto “protected” Indian lands. In a letter to Washington, Knox agonized over the possibility of Indian extermination. He observed that in the most populous areas of the United States, some tribes had already become extinct. “If the same causes continue,” he explained, “the same effects will happen and in a short period the idea of an Indian on this side of the Mississippi will only be found in the page of the historian.”3

Washington and Knox sought to provide safe havens for native tribes while also assimilating them into American society. Washington and Knox believed that if they failed to at least make an effort to secure Indian land, their chances of convincing Native Americans to transform their hunting culture to one of farming and herding would be undermined. As the two reluctantly came to recognize, however, it was the settlers pouring into the western frontier that controlled the national agenda regarding Native Americans and their land. By 1796 even Washington had concluded that holding back the avalanche of settlers had become nearly impossible, writing that “I believe scarcely anything short of a Chinese wall, or a line troops, will restrain Land jobbers, and the encroachment of settlers upon the Indian territory.”4 Richard Harless George Mason University

Notes:

1. George Washington to The Commissioners for Negotiating a Treaty with the Southern Indians, 29 August 1789,” The Writings of George Washington, 30:392 & 392N.

2. Charles J. Kappler, Indians Affairs: Laws and Treaties, Vol. II, Treaties (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904), 2:28.

3. “Henry Knox to George Washington, 7 July 1789,” The Papers of George Washington: Presidential Series, eds. W. W. Abbot and Dorothy Twohig, 2:139.

4. “George Washington to the Secretary of State, 1 July 1796,” The Writings of George Washington, 35:112.

References Native American Policy

HOMEWASHINGTON LIBRARYCENTER FOR DIGITAL HISTORYDIGITAL ENCYCLOPEDIANATIVE AMERICAN POLICY

Native American PolicyAbout the EncyclopediaContributorsWashington Research LibraryPartnersPodcastMount Vernon Everywhere!Washington’s WorldColonial Music InstituteQuotes

White Man and Red Man be One.

Two Flat Sticks

“In the forepart of the last month, about three hundred and sixty Indian, of the Kickapoos and Pattowattamies, pitched their tents on the east before this town, and tarried one night. They were on their way to the place assigned them for the land of their inheritance, being gathered by the government of the United States, fulfilling that scripture spoken by the mouth of Isaiah, which says, Behold thus saith the Lord God, I lift up my hand to the Gentiles, and set up my standard to the people, and they shall bring thy sons in their arms, and thy daughters shall be carried upon their shoulders. Their agent remarked that “they drunk no spiritous liquors,” and those who saw them can bear testimony that they were quiet and inoffensive, and different from any other tribes that have been gathered. They have a prophet, in whom they place great confidence, and he instructs them that the day is nigh, when the Great Father will send his Son on the earth; then (as he says) white man and red man be one. Their idea of what is to come to pass in the last days, the resurrection of the righteous, and their living on earth with the Lord while wickedness ceases to trouble the saints, seem to be correct as far as we could ascertain. They are very devout apparently and pray night and morning; even children and all. They have two flat sticks about one foot long, tied together, on which are several characters, which, they say, the Great Father gave to their prophet, and mean as much as a large book. They say one of these sticks, is for the old book that white man has, (the Bible) the other for the new book, (Book of Mormon) white man has it written on paper, Great Father writes it in red man’s heart. They seem to Pray from these sticks– and worship on the Sabbath with great solemnity, commencing with a salutation from the greatest or oldest to the least that can walk, and ending with the same token of friendship. Should we have time to make them a visit, we may be more particular hereafter. *From Arkansas to the Missouri, the remnants are gathering together in rapid succession, and all, as far as we have been able to ascertain, have an idea that the Great Spirit is about to do something great and good for the red man.” Evening and Morning Star (Kirtland 1835-1836 ISRAEL WILL BE GATHERED. Page 201