Sagwitch Timbimboo (1822 – March 20, 1887) was a nineteenth-century chieftain of a band of Northwestern Shoshone that converted to Mormonism. His group were the ones killed in the Bear River Massacre. Chief Sagwitch himself was injured in the massacre but survived. Sagwitch, whose name meant “orator”, was born in 1822 on the lower Bear River, in present-day Box Elder County, Utah.

In 1873, Sagwitch was baptized a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) by George Washington Hill. The rest of Sagwitch’s band, totalling about 100 people, were also baptized into the LDS Church. Sagwitch was also ordained an Elder in the church. In 1875, Sagwitch and his wife were sealed in the Endowment House, an ordinance performed by Wilford Woodruff.

In 1880, Sagwitch and his band settled Washakie, Utah. They operated a farm there. They also contributed large amounts of labor towards the building of the Logan Utah Temple.

Sagwitch’s son, Frank W. Warner, born Pisappih “Red Oquirrh” Timbimboo, who was largely raised by the Amos Warner family after his mother was killed during the Bear River Massacre, became one of the first Native Americans to serve as a missionary for the LDS Church. Sagwitch’s grandson Moroni Timbimboo was the first Native American to serve as a bishop in the church.

Journey into Southeastern Idaho

Most of the brethren who were called on this Lamanite mission made

preparations at once to fill it and on the 15th of May 1855 President Smith together with other brethren left their homes in Farmington and other places and on the 19th they arrived on Bear River north of Brigham City on the following day the 20th the camp consisting of the following named brethren were organized for traveling. Tho[ma]s S[asson] Smith President of the Mission; Francillo Durfee Captain; Wm Burgess Lieutenant, B F Cummings sergeant, D Moore Historian of the camp, Ezra J Barnard, Thos Butterfield, Wm L Brundage, Nathaniel Leavitt, Pleasant Green Taylor, Israel S Clark, Charles Dalton, George R Grant, Isaac Shepherd, Geo Browning, David H Stephens, Baldwin H Watts, Jos Parry, Ira Ames Jr, Abraham Zundel, Charles Mcgary Wm H Hatchelor and Everet Lish…

On the 15th [June] they selected a site for a fort and a tract for farming land after which President Smith returned to the main camp which moved upon the site chosen on the 18th. They called their location Fort Limhi after Limhi a Nephite king mentioned in the Book of Mormon the distance from Salt Lake City to Fort Limhi the road the missionaries generally traveled in 1855-58 was about 379 miles. source: Wikepidia/Sagwitch

Below in this chapter of “Sagwitch” you will read about incredible faith as hundreds of Shoshone Lamanites join the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

The Corinne Scare Chapter 4

1999 Sagwitch by Scott R. Christensen

“The white man is roaming all over my country and killing my game. Still I make no objection to his doing so, and all I want is to be let alone, with the privilege of making a small farm for the benefit of my people, and to be allowed to live on it in peace. I have not gone into the white man’s country and intruded on him, and I do not think it is fair for him to come into mine and drive me from my own lands without any cause, and I ask the government to take the matter in hand and reinstate me and mine on our own lands, that we may live there in peace and friendship with all men. “Sagwitch” August 31, 1875

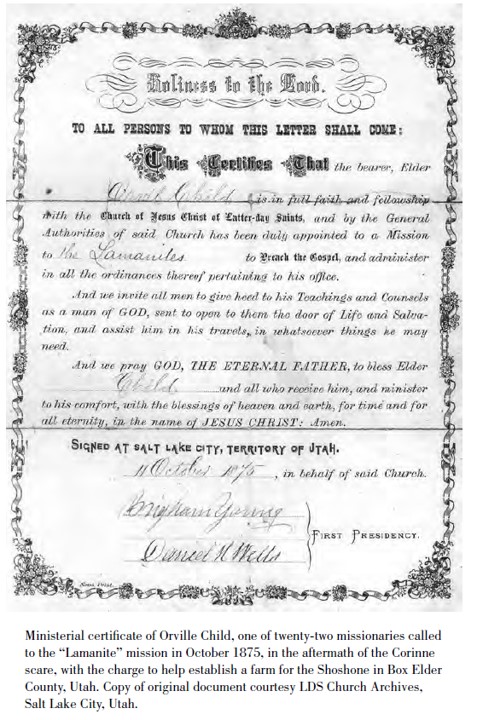

As Brigham Young announced new missionary assignments at the Mormon Church’s general conference in April 1875, he signaled his resounding support of George Washington Hill’s work among the Indians by calling fifteen men for a season of work among the “Lamanites” of northern Utah—eight more men than he called to labor in all the rest of the United States and Canada.1 Young was willing to dedicate so much manpower to the Indian cause because he anticipated a large return in Indian converts. He had been greatly impressed by the positive reports forwarded to his office in 1873 and 1874 concerning Native American converts to Mormonism. Now he wanted to see them transformed from nomadic hunters to sedentary and self-supporting farmers. As Mormonism’s prophet, he was undoubtedly anxious to support a movement that seemed to fulfill scriptural injunctions concerning the “redemption” of the remnants of the “House of Israel,” interpreted by the Mormons to be America’s indigenous peoples. Another practical benefit of the Lamanite Mission, if implemented successfully throughout the Great Basin, was much hoped for relief of white settlers from the temporal demands associated with Young’s “feed rather than fight” policies.

George Washington Hill was one of those called to labor among the Indians, and Young assigned him to head the mission. Hill’s first task was to find a suitable location for a continuation of the farming experiment begun at Franklin the summer before. The search took him north and west of Brigham City to an area about halfway between present-day Plymouth and Tremonton. In a report to President Young, Hill commented, “I went to look for a location[.] selected for permanent location a section of country lying betwen bear river and malad about twenty miles from corinne with good land and plenty of grass[.] water plenty but a heavy job to get it out.”2 The site had merit, including thousands of acres of fertile land needing only a plow and the diverted waters of the Malad River to make it productive. Young approved the location and asked the missionaries to gather there.

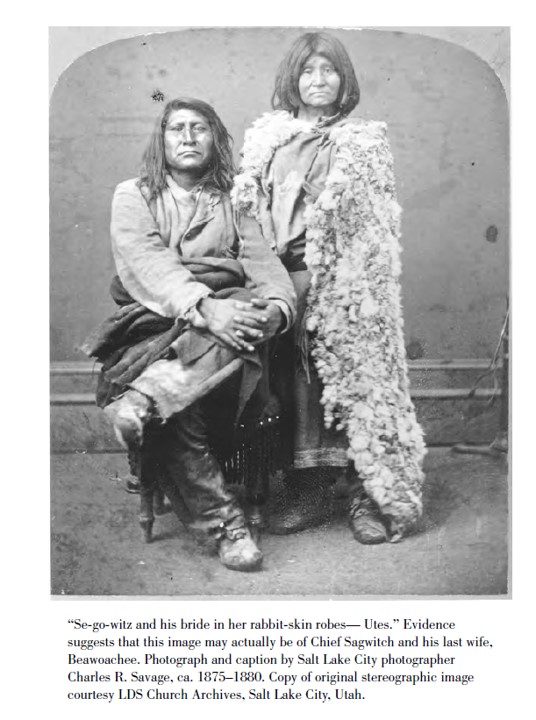

Sagwitch and his band of approximately seventy lodges returned from the Promontory region sometime in late winter. On February 22, 1875, Sagwitch and his wife, listed as Mogogah, but probably Beawoachee, along with fellow Shoshone Ohetocump and his wife, Minnie, entered the Mormon Endowment House located in the northwest corner of the temple block in Salt Lake City. They participated in sacred temple rituals and received the Mormon endowment. Afterward, Apostle Wilford Woodruff performed another ceremony that, according to Mormon belief, “sealed” each couple’s marriage in an everlasting union.3 Only a few Native Americans had received the Mormon endowment, and none had ever been sealed. Woodruff recorded the significant event in his journal: “This is not only the birthday of George Washington. But it was the day when the first Couple of Lamanites were together as man and wife for time & Eternity at the Alter in the Endowment House according to the Holy Priesthood in the last dispensation & fulness of times. Wilford Woodruff Sealed at the Altar two Couple of Lamanites. The first Couple was Indian Named Ohetocump But Baptized and Sealed by the name of James Laman. His wife Named Mine. 2d Couple Isiqwich [Sagwitch] & Mogogah.”4

Sagwitch’s band likely formed the core group of about two hundred Indians who joined Hill and the recently called missionaries at the new Indian farm in late April or early May. On May 5, 1875, Hill wrote to Brigham Young from the “Camp at Malad Dams,” reporting that “the Indians are doing all they can[,] ploughing with their own horses[,] holding the plows themselves and seem to be very anxious to learn to work[,] are well pleased with their location here.” Hill expressed anxiety over the fact that “the land is drying up very fast” and added that “we want to get to work on the Dam as soon as we can.”5 “Taking hold of their work well,” the Shoshone converts and the missionaries filled the newly plowed ground with a hundred acres of wheat, twenty-five acres of corn, five and one-half acres of potatoes, and between six and eight acres of peas, beans, squashes, melons, and other vegetables.6

The Shoshone who worked alongside Hill exercised great faith in their Mormon hosts and in the farming experiment. By choosing not to pursue their traditional springtime food-gathering activities, they traded a tried and tested lifestyle for one that could promise no results until the autumn harvest. Without the spring harvest, the natives were left nearly destitute, having as usual exhausted most of their food stores during the cold winter. Hill worried about the condition of his charges, and wrote to Young: “The Indians feel well are very much encouraged with their prospects only one thing troubles them and that troubles me as much as it does them and that is something for them to eat until it grows so that they can keep on at their work—they are willing to work every day but they are like other people, they cannot work mutch without eating.”7 It is not known whether Hill’s request for food was granted, but the Shoshone continued to labor diligently at the farm.

After the Indians finished planting their crops, they began working in earnest on damming the Malad River. It soon became apparent, however, that the job could not be completed in time to divert water onto the dry ground and save the already-planted crops. Alvin Nichols, bishop of the Brigham City Ward, recommended the Indians plant their crops instead in the Bear River City field, a communally held Mormon property that he offered to them free of charge for the season.8 Hill also had discovered that water from the Malad was alkali and generally unhealthy. He accepted Nichols’s offer and reported that in “the latter part of may moved our camp on to bear river on account of the water being bad in malad.”9

His decision was based on other considerations as well. In a letter to Young, Hill noted that “taking into consideration the heavy job of getting out the water and fencing the land and the lateness of the season I accepted the offer of what land we wanted in bear river field and went to work.”10 As had been the case with the abandoned Franklin farm the year before, Hill and the other missionaries again told Sagwitch and his people to relocate, leaving behind the freshly turned soil and wilting crops as evidence of their conversion to Mormonism and an agrarian life.

The new farm, located just outside of Bear River City, five miles from Corinne, looked very promising, offering as it did an abundance of land and water for the Indians’ use. The missionaries and the Shoshone immediately went to work, preparing the land and planting “nearly one hundred acres of wheat[,] about twenty five of corn[,] five and a half acres of potatoes[,] three to four acres of other stuff.”11 Hill soon discovered that this land also was not all he had hoped it would be. After farming there all summer, he concluded that “I do not think they could have selected a poorer peace of land in utah of the same size than bear river field.” Hill found the difficulty of irrigating the field especially frustrating: “There was quite an amount of the land that was recommended to me that when we come put the water on, it was higher than the water so that it would not water.” Nevertheless, the crops grew well where they could be watered, and even the wheat that could not be irrigated “was short but [had] tolerably fair heads.”12 Under Hill’s direction, Sagwitch, his people, and the missionaries began building a canal from the Bear River to their fields.

The dedication and civility of the Indians at the camp impressed visiting newspaper reporters. One Deseret Evening News writer viewed the Indians as “exceedingly industrious, working as faithfully and almost as expertly as white people.” He noted that the young Shoshone men “do the laborious work, and attend to it without murmuring . . . They have their own horses, and plow, sow and do other farm work with readiness.”13 It must have been a truly unusual sight—proud Shoshone warriors using their prized Indian ponies at the plow, a people who cherished mobility trading all of their resources for a sedentary farming life. The nature of the new work necessitated the replacement of traditional gender roles with ones that eliminated hunting, raiding, and warring and placed husbands in the fields with their wives. The transition must have been difficult, though Anglo witnesses reported positive responses from the Indians.

Many of the natives were apparently very happy with the camp

and wished to make it their permanent home. A reporter noted that the Indians “declare their intention to wander about no more, but to lead industrious and respectable lives, at peace with all their fellow creatures.” He added that the Indians were presently camped out, but expressed “great anxiety to begin to build houses and live in them like white people, and as soon as the site of the settlement is decided upon, which will be when a canal now being constructed is fully located, the erection of dwellings will be commenced.”14 In the early part of June, large numbers of Shoshone, “Pah Utes,” and Bannocks began to arrive at the camp from all directions, joining the core group of Indians under Sagwitch.15 The influx amazed Hill. He recorded in his journal, “I did not send any word to those Indians who were situated at a great distance, as I expected to labor only with those who were near the settlements. Still those that were located at a distance of from four to eight hundred miles apparently knew as much about my actions as those did among whom I was then stationed, for they came in from every quarter to see and hear me.”16 Like a magnet, the camp began pulling Native Americans to it from every point on the compass.

Hill’s experience was not unique. He had witnessed only one part of a larger religious movement involving Native Americans and Mormonism. While this movement enjoyed enthusiastic support in Utah’s northern reaches, reports from Nevada, Arizona, Idaho, and all parts of Utah confirmed that the whole region was alive with a kind of Native American religious revivalism. In Salt Lake City, for instance, aging Indian interpreter Dimick B. Huntington became overwhelmed by hosts of Native Americans coming to the territorial capital seeking baptism. In a June 1875 letter to Apostle Joseph F. Smith, Huntington reported: “They are coming in by hundreds. There has been 2,000 baptisms already. I have more or less to baptize every week.” Huntington added that he had become aware of nine tribes on their way to be baptized and then concluded, “O Joseph, how I do rejoice in it! They are coming in by hundreds to investigate, are satisfied and are baptized.” The number of natives demanding baptism became so great that Huntington hired builders to erect a baptismal font in his front yard.17

In the St. George area, photographer Charles R. Savage witnessed the same phenomenon when he happened on a huge gathering of “Shebit” (Shivwit Paiute) Indians who had gathered for Mormon baptism at a pool north of the city. As the religious service began, Savage was impressed that “these swarthy and fierce denizens of the mountains knelt before our Eternal Father with more earnestness of manner than some of their white brethren. I shall not forget the sight—some three or four hundred persons kneeling, Indians and Caucasians, side by side; men who had faced one another with deadly rifles seeking each other’s blood were mingled together to perform an act of eternal brotherhood.”18

A California newspaper reporter noted that all of the Indians in Loanville, Nevada, had gone to Utah to join the Mormon faith,19 and in June 1875 at Kanosh, Utah, Mormon bishop Culbert King baptized eighty-five Indians, including the settlement’s namesake, Chief Kanosh, who reportedly spoke “with much earnestness, exhorting his followers to industry and good works.”20 Meanwhile, at Mount Pleasant, Utah, fifty-two members of Joe’s band personally built a baptismal font by damming up a stream, thus facilitating their entry into Mormonism.21

Mormon leaders expressed their excitement over these events in the church’s newspaper in Salt Lake City. Beginning in late 1874, articles reported that the conversion of hundreds of natives had been in response to appearances of heavenly personages who told the natives to request Mormon baptism, renounce their nomadic ways, and take up farming.22 To the editors, who undoubtedly voiced popular Mormon thought, this turn of events was nothing less than the fulfillment of Book of Mormon prophecies and an additional witness to the truth of the Mormon gospel. A July 1875 editorial answered those of a more cynical bent by assuring the public that the recent baptisms of Indians had only been performed when the elders had “been convinced that they were sincere and had a reasonable understanding of the nature of the ordinance, and the responsibilities involved in accepting it.” The editor also insisted that whether applicants for baptism be of Caucasian, African, or American extraction, they must be allowed membership in the Lord’s kingdom, because “God is no respector of persons.” The editor concluded by assuring his readers that with the Mormon gospel also came instruction in the habits of industry and honesty, which would bring “peaceable fruits of righteousness.”23

While the Mormons openly rejoiced in their new converts and made significant efforts to settle them as farmers, Fort Hall’s Indian agents struggled to support their charges. The reservation that had been home to various Shoshone and Bannock bands since 1869 had never been alloted enough foodstuffs to care adequately for its residents or to meet treaty obligations. Fort Hall agent James Wright soberly wrote to the commissioner of Indian affairs on February 6,

“We have flour enough on hand to issue to them until April 1st. We can also let them have potatoes occasionally. We have beef for one more issue. Now what will be done with these people . . . They cannot get out to hunt, there are no roots to be had, [and] fishing time will not have come.” Wright pleaded, “Surely the Committee on Indian Affairs will allow us money to subsist these people on their reservation.”24

By the following week, Wright reported that he had purchased some cattle without prior approval to feed the “suffering” Indians and hoped that the department would approve his “act of mercy” on their behalf. He added, “What the Indians are to do after this weeks issue I am unable to tell. I will issue flour, and coffee as long as I have it to issue.”25 Not long after Wright penned these dismal reports, he resigned and was replaced in July 1875 by William H. Danilson. The new agent assessed the reservation’s food supplies and discovered that the resources on hand could only furnish each Indian with one meal a day for two days each week. Faced with the prospect of absolute starvation on the reserve, he broke with policy and sent the Native Americans out from Fort Hall to fend for themselves.26

Conditions were not much better for the Shoshone at the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming Territory. Agent James Irwin reported that after the spring planting “the Indians were permitted to go out and hunt until supplies could reach the agency.”27 Many of the hungry Indians thus evicted chose to join relatives and friends on the lower Bear River, where the Mormons welcomed them and offered both food and lessons in farming.28

George Washington Hill joyfully greeted these refugees and began to teach them the rudiments of agrarian living. He also held meetings almost daily wherein he explained Mormon doctrines and invited the converted to be baptized. Hill soon found that his activities as a proselytizer took most of his waking hours and left little time for farming. To speed up the process, he developed a visual aid to illustrate the tenets of the Mormon faith as well as the Indians’ Israelite origins as expressed in the Book of Mormon. A daughter-in- law of Hill’s described his teaching methods in the following terms:

Sometimes they received [the Mormon gospel] very readily. It seemed as though they were anxious for it. Of course, there were some who were not. He had to talk more to some. But he was a good hand to talk to them. He had a scroll with pictures of the authorities and the Book of Mormon. It was a big scroll, about that square [18 inches], and he used to have that when he talked to the Indians, and turned to different characters and told them about their forefathers. I do not know what became of that scroll, but I know grandpa had it. It had nice large pictures of the different Nephites and different leaders. The Book of Mormon tells about them. He had pictures taken on purpose for that, so that they would have something to look at. They were like children and he could explain it to them better. I have seen him have this scroll and talk to the Indians, and show them the different pictures and they were quite interested in it.29

Hill had ample opportunities to use his teaching scroll. On June 7, 1875, he assembled a large number of recent arrivals and “preached to quite a crowded congregation when they were calling for Baptism so loudly we went to the water and I Baptised one hundred and sixty eight before coming out of the water, and 7 the next morning.”30

Thus went the mounting conversion of Indians to the Mormon faith. So great were the numbers of natives asking for baptism that Hill’s account of his activities in the summer of 1875 eventually omitted all description of farming and settlement activities and instead focused on trying to list each Indian’s name correctly so that it could be forwarded to Salt Lake City for inclusion on the church’s permanent membership record. In a report Hill sent to Brigham Young on August 25, 1875, he tallied the Indian baptisms: “I find by looking over my work that I have baptised this season if I have not made a miss count eight hundred and eight which with 102 that I baptised two years ago and sixteen I baptised last summer and fifteen baptised by James H. Hill makes a total of nine hundred and thirty nine that belong to this mission.”31

The Indians’ enthusiasm, devotion, and desire to emulate their white brethren in many facets of life showed that Hill’s tally represented more than mere statistics. Perhaps no event better epitomizes the apparent Shoshone desire for acculturation than the Pioneer Day festivities held in Brigham City on July 24, 1875. Hill came to the celebration with eight hundred native converts, almost certainly including Sagwitch and his band. At about 11:00 A.M., Brigham City residents witnessed an imposing sight in front of the courthouse as three hundred Shoshone men and women drew their horses into a triangular line on the square while local bands played spirited tunes and artillerymen fired off several blasts. Then an Indian convert called James Brown gave a brief address. Afterward, the Indians corralled their steeds and joined their Scandinavian, English, and Welsh brothers and sisters in the Brigham City bowery. The speakers included the mayor, two city judges, resident Apostle Lorenzo Snow, and James Brown and John, two of the Shoshone converts. They addressed the audience with great zeal and spirit and “bore testimony of the Lord’s visitation among them.” They also said that they “had warm feelings towards the people, admired the fine appearance of the young people, desired to become civilized, build, plant and become like their white brethren.” Before the day was out, all present joined in a mighty shout of Mormonism’s sacred cry: “Hosanna! Hosanna! Hosanna! to God and the Lamb.”32

The leaders in Brigham City must have been fully impressed, because on August 1, a delegation of dignitaries from the county seat, including Apostle Lorenzo Snow, visited the mission on the Malad. They could barely squeeze into a bowery filled with a thousand Indians, including about 450 Shoshone from Wind River, 150 Bannocks from the Idaho area, and a large group of local Indians, including Sagwitch’s band. The silence and attentiveness of the Indians astounded the apostle and his poetess sister, Eliza R. Snow. As Hill concluded his sermon, three hundred Indians demanding immediate baptism swept him out the door and to the river.33 Hill’s success continued, adding scores of Indian converts to the church rolls, including Shoshone chieftain Pocatello.34 Hill must have been a little overwhelmed in early August to hear that an additional five hundred Indians were en route to the camp to join with the Mormons.35

Successes in befriending, teaching, converting, and settling Native Americans made George Washington Hill and the Mormons ecstatic, while agents from the adjoining reservations grew increasingly concerned. Fort Hall agent James Wright visited the Mormon Indian farm in May 1875 and found several hundred Indians there, mostly Shoshone from the Wind River Agency, though he discovered some Indians from Fort Hall who, he noted, must have “run off without my knowledge.” He reported to the commissioner of Indian affairs that “These Indians are being operated upon by the Mormons, many of them Baptized, others taken through the ‘Endowment House’ (whatever that is or means) and then called ‘The Lords Battle Axes.’” He cautioned that “All this means mischief” because it had a demoralizing effect on those Indians left behind at Fort Hall. He urged that all Indians not on their proper reservation be “removed from Utah” as soon as possible.36

Wright was even more certain of his position by the end of June. He reported to the commissioner on June 31 that it was now “impossible” for him to keep the Indians at Fort Hall. “They go away in the night and when they return deny that they have been there and when pressed get mad,” he noted, adding that “Unless the Indians are very soon taken out of Utah there will be trouble.” In the same letter he plead for additional resources that would enable him to adequately supply, and thus keep, the Indians at Fort Hall.37

Wright’s successor, W. H. Danilson, was even more direct. In a July 31 letter to the commissioner, he stated that he “exceedingly” regretted having to release the starving Indians from the reservation, noting that “Large numbers have gone and are still going to Utah to get washed and greased and enrolling themselves in the cause of the Mormons.” He added that the Mormons had been teaching the Indians that they were the “chosen ones” to establish the kingdom of God on earth and that they should hate the government and distrust its agents. “The whole Mormon influence is bad and calculated to turn these people hostile to the government their only true friend,” Danilson declared.38

The presence of so many Indians in the area also annoyed the residents of Corinne, just five miles from the Indian camp. The ever increasing population of Indians on the fringes of the town caused the editor of the Corinne Daily Reporter on July 9, 1875, to write, “The valley is swarming with Indians who belong to the Fort Hall agency, and should be kept on the Snake River reservation. We are informed that the authorities at Fort Hall say that it is impossible for them to keep the Indians where they belong while the people are constantly making them presents and urging them to stay here.”39 The editor’s tone in the following three weeks turned from annoyance to near panic as the number of Hill’s charges swelled to nearly two thousand souls.” Chapter 4 Segwitch by Scott Christensen

This was just Chapter 4. To read the entire book visit HERE! 1999 Sagwitch by Scott R. Christensen

As a small Shoshone boy, Be-shup (Red Clay), told of his survival of the 1863 Bear River Massacre. He had chosen to remain in the collapsed wheatgrass tipi on the frozen ground. When he finally left the tepee, he was cold and scared and wounded seven times, being severely wounded in the shoulder. He wandered around in a daze until he was found by a relative. In his cold little hands he carried a bowl of frozen pine-nut gravy. Food was so precious to this little two year old boy that he had clung to his bowl all day long. The boy was a son of Chief Sagwitch. His father told him that his mother, Tan-dab-itche, was dead and his baby sister was left in a tree in hopes that she would be picked up and cared for. At this moment in his life, the little boy could not utter a word or cry? He was bewildered, frozen in grief, and in shock.1

Be-shup rejoined his father and the rest of the wounded and frozen children and left with William Hull who saw some of the battle, and helped care for the survivors. He said, “They were very willing to go with us. We took them on our horses to the sleigh, and made them as comfortable as possible.” Sagwitch later camped at the home of Jonathan Packer in Brigham while Mr. Packer cared for him and dressed his wounds. After Sagwitch had recovered he left his son with his brother-in-law, Uncle Tom, and left on a buffalo hunt. The young papoose was too much for his uncle’s patience, so he took the boy to Willard and traded him to Salmon Warner, father of a Mormon family in northern Utah, for “a bag of beans, a sheep, a sack of flour, and a Mormon quilt.”2

Later Salmon Warner traded the boy to his brother, Amos Warner. Be-shup was adopted by Amos and Phebe Warner and given the name of Frank Warner. “Frank remained in this home until he grew to manhood, receiving just as good treatment and advantages at home and in school as the other Warner children. Frank was bright, intelligent, had a happy disposition, a good moral character, and was very fond of fun. He showed marked ability in writing and learned the palmer method and fancy scroll writing.”3

From his Mormon parents and from his father, Sagwitch, Warner inherited a mixed set of beliefs and attitudes that strove within him for the rest of his life. Warner “received a common school education, showing marked ability in penmanship. He made ties, burned charcoal and when the Oregon Short Line Railroad was built from Granger to Pocatello, helped build the grade to Soda Springs Idaho.”4 He graduated from Brigham Young College in Logan and earned a living teaching penmanship and reading to farm families, driving his horse and buggy “from farm to farm, town to town, up and down the Cache Valley.”5

While yet a young man he married an English woman, Edna Davis, of Paradise, Cache County, Utah, in the endowment house in Salt Lake City, Utah. They had four children.

Frank Warner was one of the first Native Americans to serve as a missionary for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Warner was an involved and committed member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as demonstrated by the three missions he served for the church among Assiniboines, Dakotas, Yanktons and Hunkpapas, on the Fort Peck Reservation, and among his own Shoshone people, as well as the Paiutes and Bannocks in Utah and Idaho.6

Frank was known to have great faith, even to the healing of the sick. One instance, while he was on one mission, he knew his wife Edna had a cancer on her nose. Communication in those days was not as we have it now; it was slow and erratic, and he knew of her malady before she wrote him a letter, His diary tells of his awareness, of his prayers and fasting, and of his confidence in the Lord healing her. Upon his return home she was cleared entirely of her ailment.7

His first wife was killed in an automobile accident. He later married an educated lady, Georgianna Flinn “Georgie”, from Vermont. Mr. Warner died of Spanish influenza in January of 1919.”8

1 Mae Parry research. Oral tradition from family and other survivors.

2 Scott R. Christensen, Sagwitch: Shoshone Chieftain, Mormon Elder 1822-1887, (Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 1999), 67.

3 Ernest Wayne Warner, Granddad’s new Heritage.

4 Carter, Our Pioneer Heritage, v. 8, 88.

5 Hart, Bear River Massacre, 157-159.

6 Carter, Our Pioneer Heritage, v. 8, 88.

7 Ernest Wayne Warner, Granddad’s new Heritage.

8 Carter, Our Pioneer Heritage, v. 8, 88.

Compiled from:

Captivity, Adoption, Marriage and Identity: Native American Children in Mormon Homes, 1847-1900. Michael Kay Bennion University of Nevada, Las Vegas, [email protected]

Adopted Father

Amos Warner

Born: May 9, 1839 Sangamon County, Illinois, USA

Died: Apr. 14, 1906 Bear, Adams, Idaho, USA

Married: Oct. 9, 1865 Endowment House, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake, Utah, USA

Adopted Mother

Phebe Eliza Harding Warner

Born: Aug. 23, 1845 Nauvoo, Hancock, Illinois, USA

Died: Sep. 2, 1909 Bear, Adams, Idaho, USA

Source: Findagrave