“And now I, Moroni, proceed to give an account of those ancient inhabitants who were destroyed by the hand of the Lord upon the face of this north country.” Ether 1:1

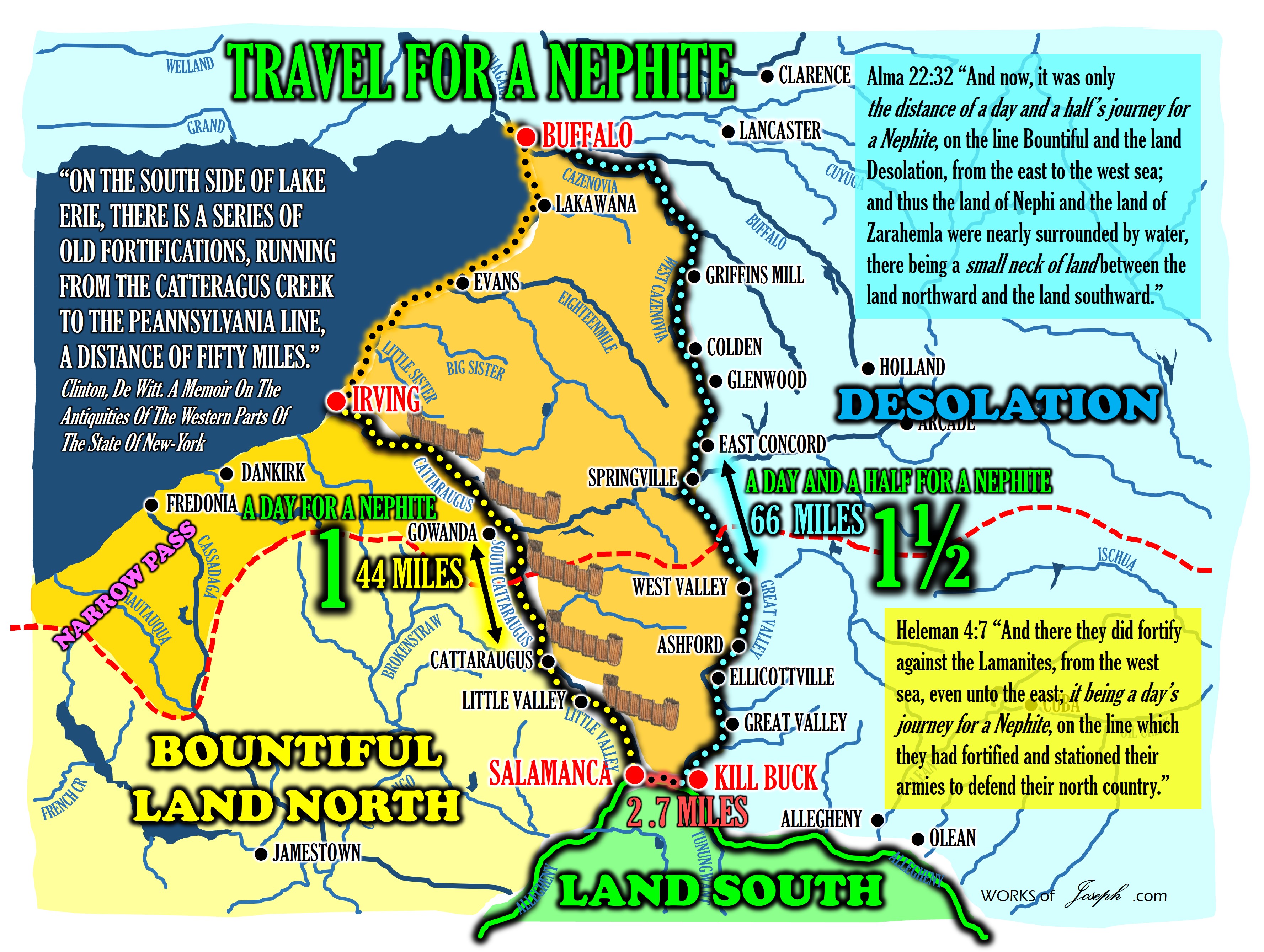

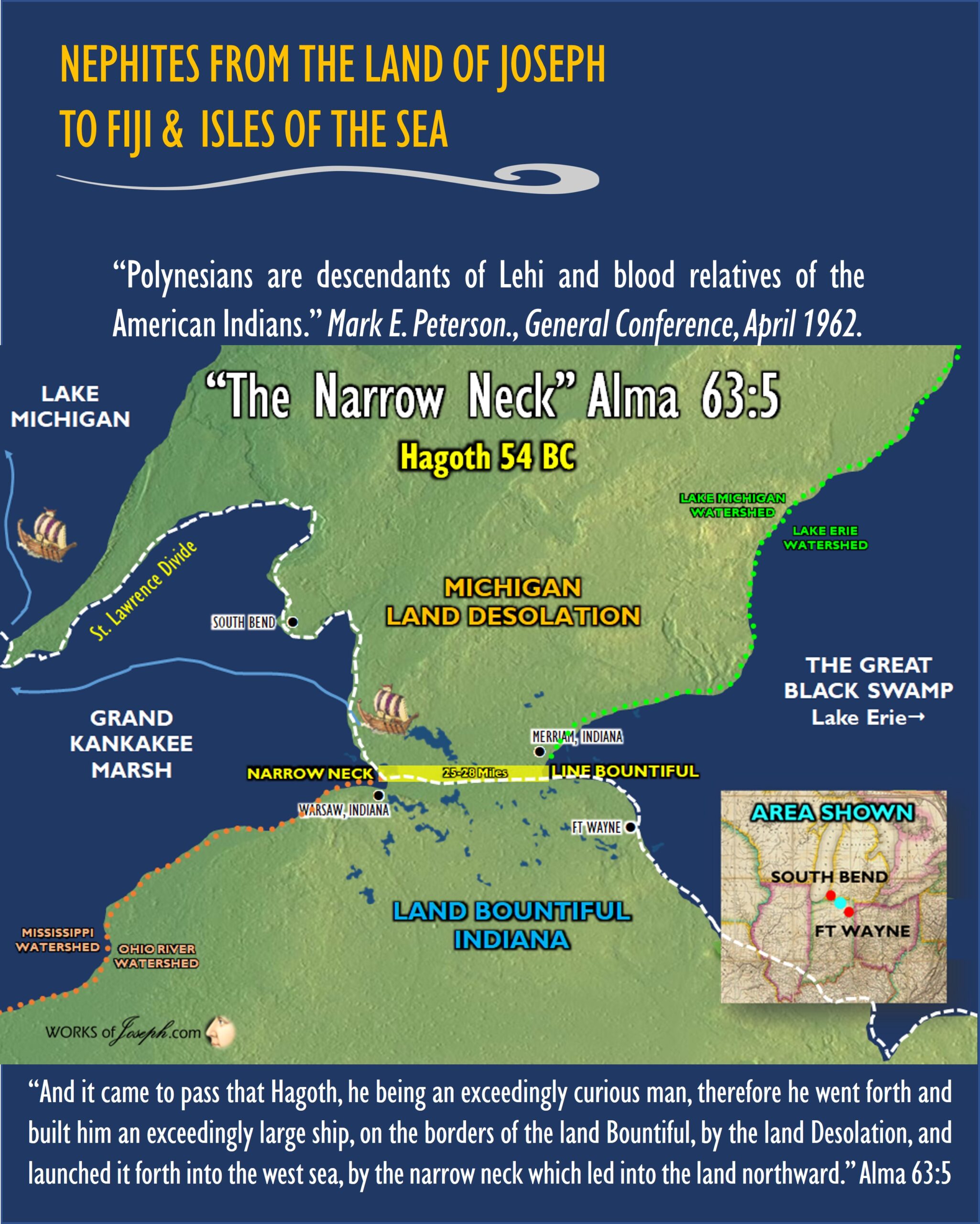

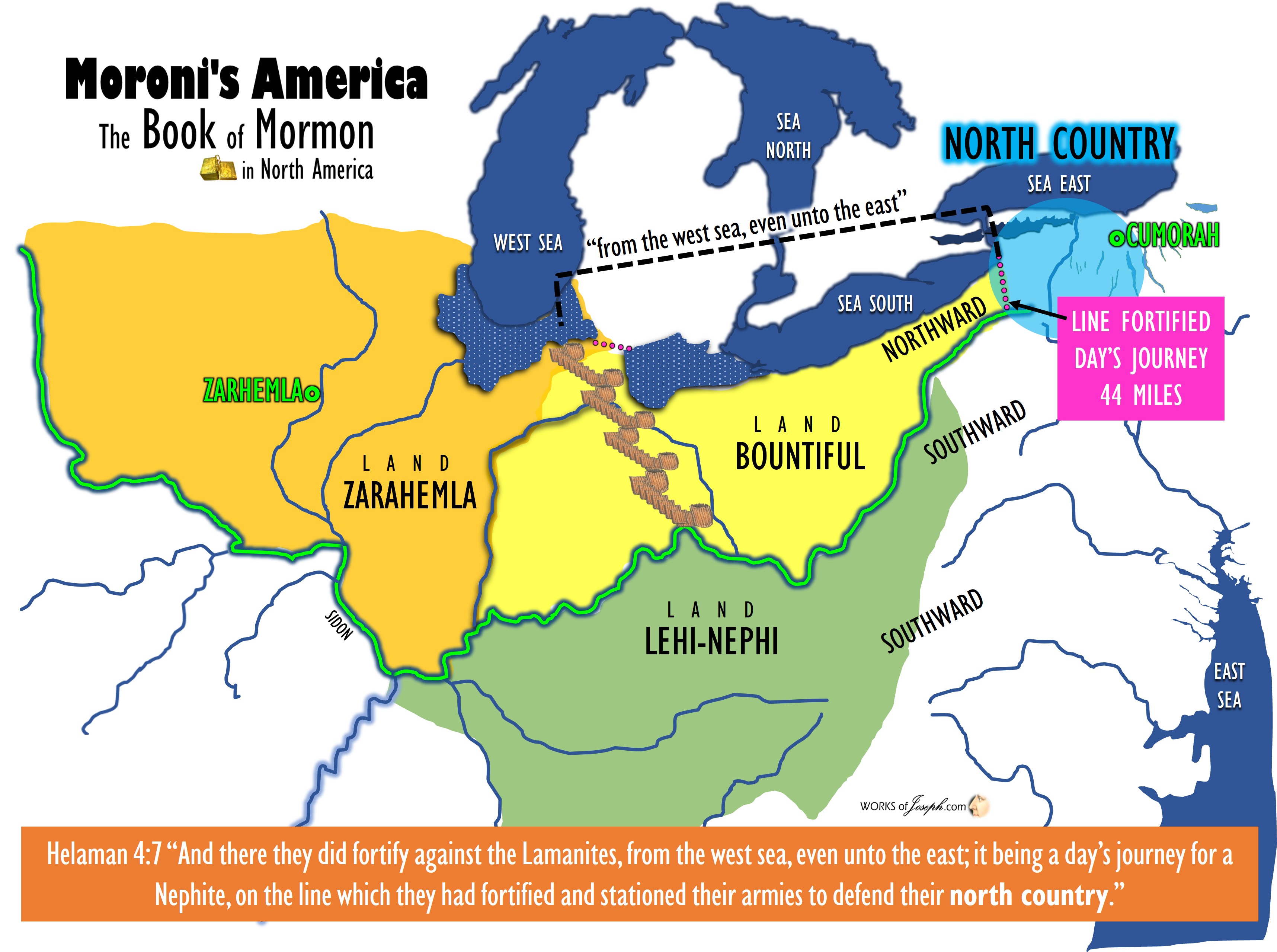

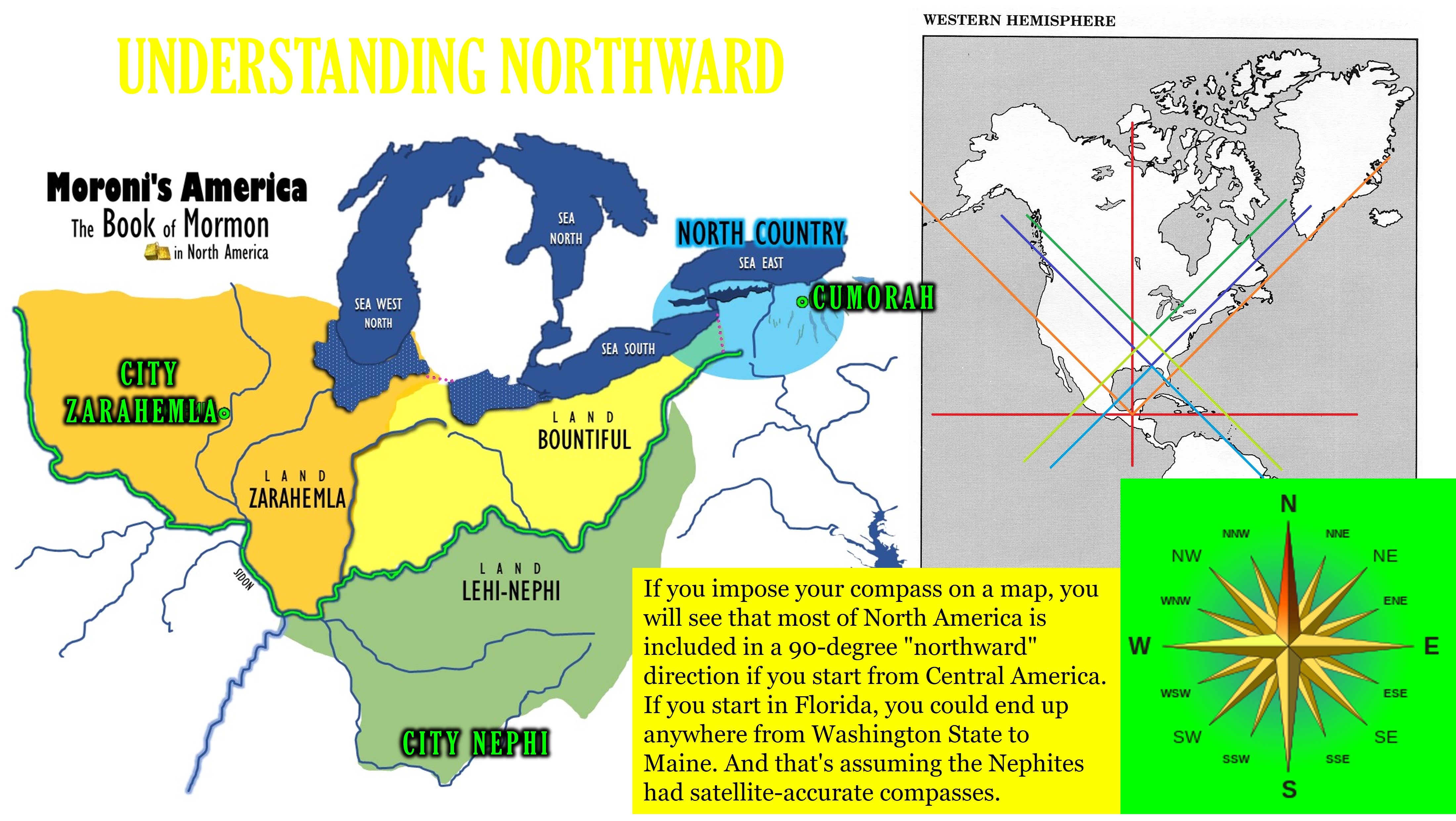

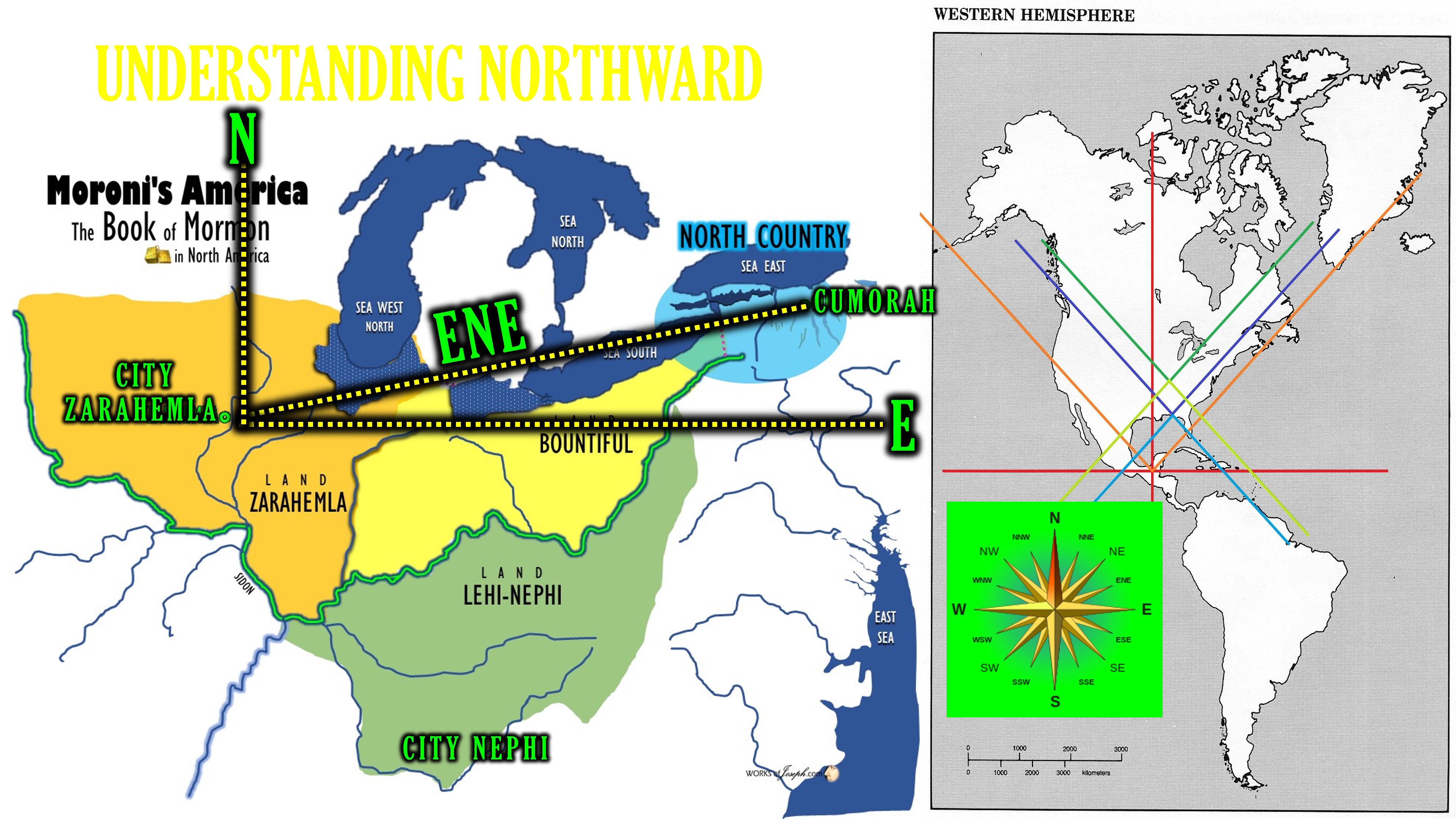

As you read the words and view the maps below, you will have a keen understanding of exactly where the “North Country” is, according to Ether 1:1. Once you understand the Book of Mormon most likely occurred in North America and the Narrow Neck of Land is the Niagara Peninsula, it will be easy to understand where the North County is located.

From Moroni’s America we read, “As I read this scripture, there is little doubt that Moroni lived near Hill Cumorah as he abridged the Jaredite record near where he would later bury the record along with the Nephite records. Is there any common sense doubt, that this is so?

“Ether 7:6… “near the land” is fairly vague… but at least we know it is around the Great Lakes, in the “north country” where Moroni lived when he wrote this record.

From Moroni’s perspective, writing in the north country, Zarahemla would be southward… the great Jaredite city was between the land northward (sometimes referred to as Desolation) and the land southward (which Ether 9 called Zarahemla, which included Bountiful). .. In reference to Buffalo [NY] (the proposed site of the great city), the land northward was the Niagara peninsula and further north and west of there.” Moroni’s America

Chapter 22 Moroni’s America

– Moroni

Moroni focuses on the geography of the soul.

He writes nothing about the lands of the Nephites. He includes an epistle from his father that references sites not otherwise mentioned in the text: the tower and land of Sherrizah and the abominations of the Nephites in Moriantum. Both locations symbolize the darkest recesses of the human soul, and the end of the epistle contrasts that darkness to the light of Christ.

Sherrizah had a tower, presumably a fortress but possibly a steep ridge or hill, from which the Lamanites took prisoners, men, women and children. They killed the men and fed their flesh to their wives and children (Moroni 9:7-8). The Lamanites left some widows and daughters behind in Sherrizah but took all the food, so “many old women do faint by the way and die.” Mormon was unable to rescue them because the Lamanite armies were “betwixt Sherrizah and me” (Moroni 9:16-17).

Moriantum was another Nephite land, but here, it was the Nephites who were depraved. They took Lamanite daughters prisoner, raped them, tortured them to death, and then ate their flesh (Moroni 9:9-10).

Mormon concludes his epistle in Chapter 9 by looking away from the darkness of the souls of his people and turning to Christ:

25 My son, be faithful in Christ; and may not the things which I have written grieve thee, to weigh thee down unto death; but may Christ lift thee up, and may his sufferings and death, and the showing his body unto our fathers, and his mercy and long-suffering, and the hope of his glory and of eternal life, rest in your mind forever.

26 And may the grace of God the Father, whose throne is high in the heavens, and our Lord Jesus Christ, who sitteth on the right hand of his power, until all things shall become subject unto him, be, and abide with you forever. Amen.

Moroni’s writings also display the geography of his own soul.

Even when he is pursued by the Lamanites, those fierce warriors who will kill him because he will not deny the Christ, Moroni risks his life to “write a few more things that perhaps they may be of worth unto my brethren, the Lamanites, in some future day, according to the will of the Lord” (Moroni 1:4).

In his final chapter, Moroni writes about how each individual can navigate through the geography of his or her own life. He shows that the power of the Holy Ghost lets each person know “the truth of all things” (Moroni 10:5), including the record of the Nephites. He explains how spiritual gifts guide us through the challenges of life, avoiding or overcoming obstacles we encounter.

The one place where Moroni writes about borders is metaphorically, in speaking of the establishment of Zion.

31 And awake, and arise from the dust, O Jerusalem; yea, and put on thy beautiful garments, O daughter of Zion; and strengthen thy stakes and enlarge thy borders forever, that thou mayest no more be confounded, that the covenants of the Eternal Father which he hath made unto thee, O house of Israel, may be fulfilled.

This seems to be Moroni’s hope not only for the promised land—for America—but for every land and nation and people who embrace the covenants.

Chapter 23 – Evidence, Proof, and Historicity

People often ask me, “How much evidence does it take to prove something?” My answer: “It depends on the individual and what he or she wants to believe.”

When I was a prosecutor, preparing a case for trial involved assembling and presenting evidence to prove elements of a crime beyond a reasonable doubt. In civil cases, the burden of proof is a preponderance of the evidence, meaning more likely than not. There are statutes and rules and court decisions about the fine points of these formal standards of proof.

But no such rules apply to our individual lives.

A person who wants to believe something will be convinced by little, or no, evidence. A person who doesn’t want to believe something may not be convinced by any amount of evidence. But most people, in most aspects of their lives, do tend to want to know the truth, even if it is “hard” because it contradicts what they’ve been taught or what they’ve believed before.

I wrote this book to offer evidence about the historical authenticity—the historicity—of the Book of Mormon.

In my view, the Mesoamerican theory has eroded faith in the Book of Mormon among those who look objectively at the evidence and arguments. The “evidence” usually cited to support Mesoamerica as the setting for the Book of Mormon narrative is illusory. Proponents find similarities between Mesoamerican culture and the culture described in the text of the Book of Mormon, but such similarities occur in many human cultures. Worse, they contradict the plain meaning of the text, which describes a Hebrew culture, not a Mayan one.

These similarities or “correspondences” are often dressed up in sophisticated rhetoric, but they boil down to this:

Therefore, Nephi was a Mayan.

I realize no Mesoamerican proponents have made that specific argument, but the correspondences you read about—John Sorenson alone had 140 such correspondences in his book, Mormon’s Codex—follow that logic.

Meanwhile, the Mesoamerican proponents distort the text so it will fit their theory. Mormon’s Codex and many other publications and web pages that support the Mesoamerican theory claim the textual term “north” doesn’t really mean north. They substitute Mayan animals and plants for those mentioned in the text. They also insist Joseph Smith was merely speculating about where the Book of Mormon took place.

If you’re wondering where the Mesoamerican theory originated, Chapter 29 (Moroni’s America) addresses that.

Any standard of proof is subjective. Proof is whatever is sufficient to satisfy an individual about the truth or falsity of a given proposition. Because of different backgrounds, priorities, and values, some people require more proof of a given proposition than others. This subjectivity explains why we use juries in courts of law and peer reviews in science. In both cases, we assume that if evidence persuades a group, it is more likely to be accurate. Convince enough people—members of a jury, qualified scientists—and the law and public opinion will generally go along with the conclusion.

Yet human judgments are fallible. History is replete with examples of a “consensus” being wrong. Einstein famously challenged the consensus of his day with his own theory of relativity. The germ theory revolutionized medicine. Technology in all its forms has challenged prior consensus and dramatically changed the way people live and think.

Along the way, every challenge to the consensus faced opposition. Individuals with strong convictions used evidence and rational arguments to persuade others, but it is almost always a gradual process. What may be considered as “fact” in one time and place may be shown to be error in another time and place. New knowledge supersedes old, but old knowledge may be sustained when seen from a different perspective. Even where people agree on a set of facts (which itself can be a challenge), they differ regarding the interpretation and importance of those facts.

Religious leaders face similar obstacles. Moses presented a tremendous challenge, not only to the Egyptians but to the Israelite slaves who had grown accustomed to their status. Many prophets and religious leaders have been killed for what they preached. Jesus was crucified. Stephen was stoned. Many of the original apostles were killed.

When it comes to personal convictions, the views of a majority are irrelevant. Belief in God is an individual choice, not the product of a vote. In the same way, one’s acceptance or rejection of the Book of Mormon is highly personal, and may be the product of objective reasoning based on facts, spiritual insights based on personal experience, or a combination of the two.

In my view, even spiritual choices are improved with consideration of the best available evidence.” Moroni’s America by Jonathan Neville Page 261-267