See the New June 27, 2022 FIRM Foundation Newsletter Now

A Special Zoom Call June 30th 7 pm

Mound Builders

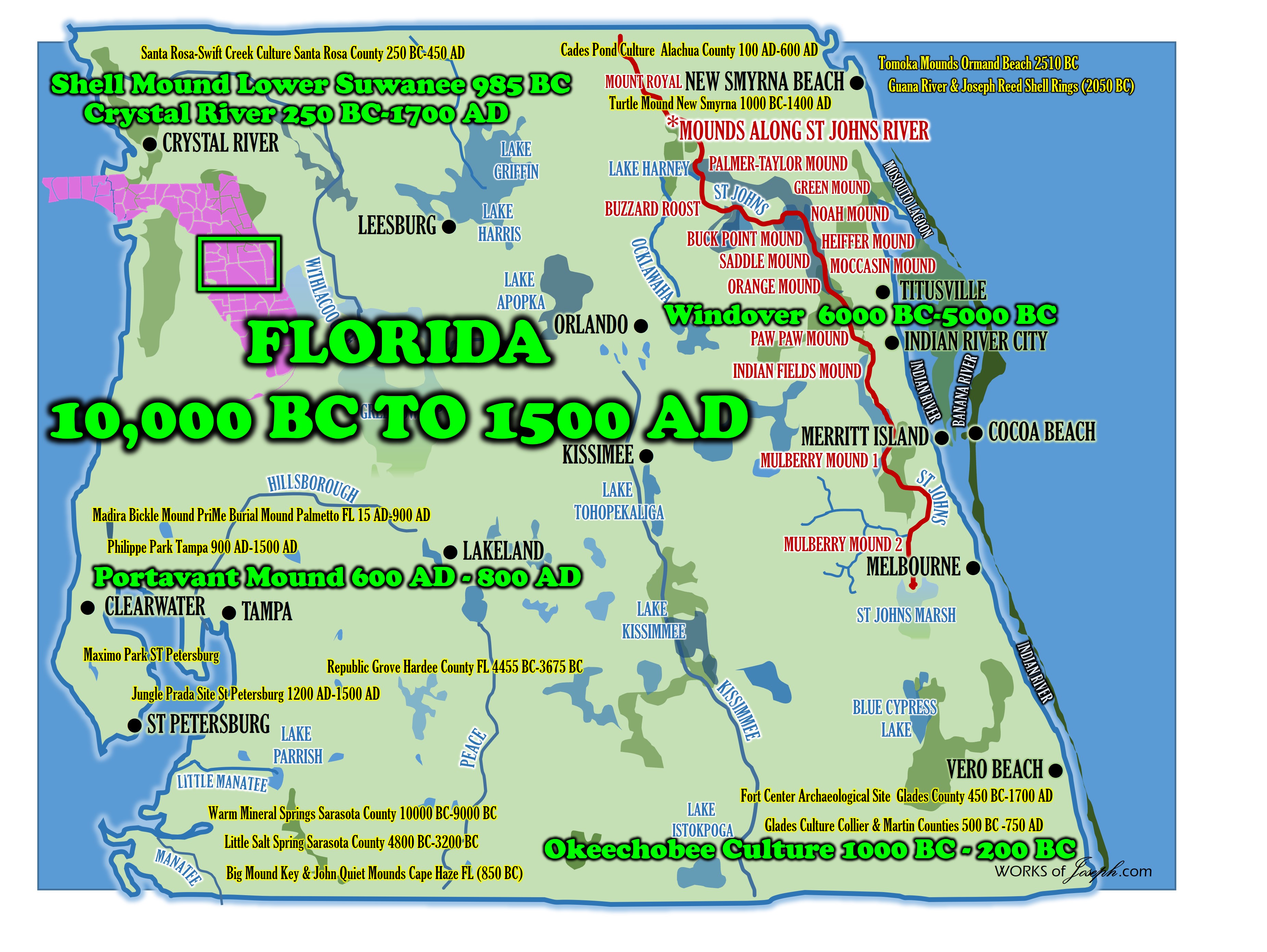

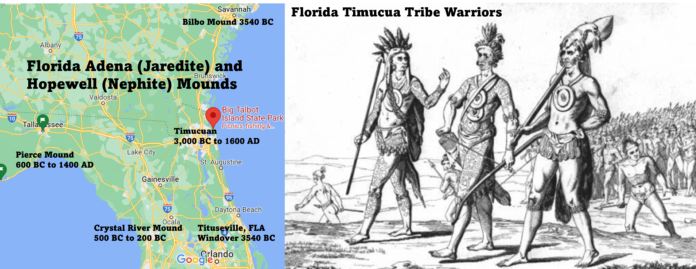

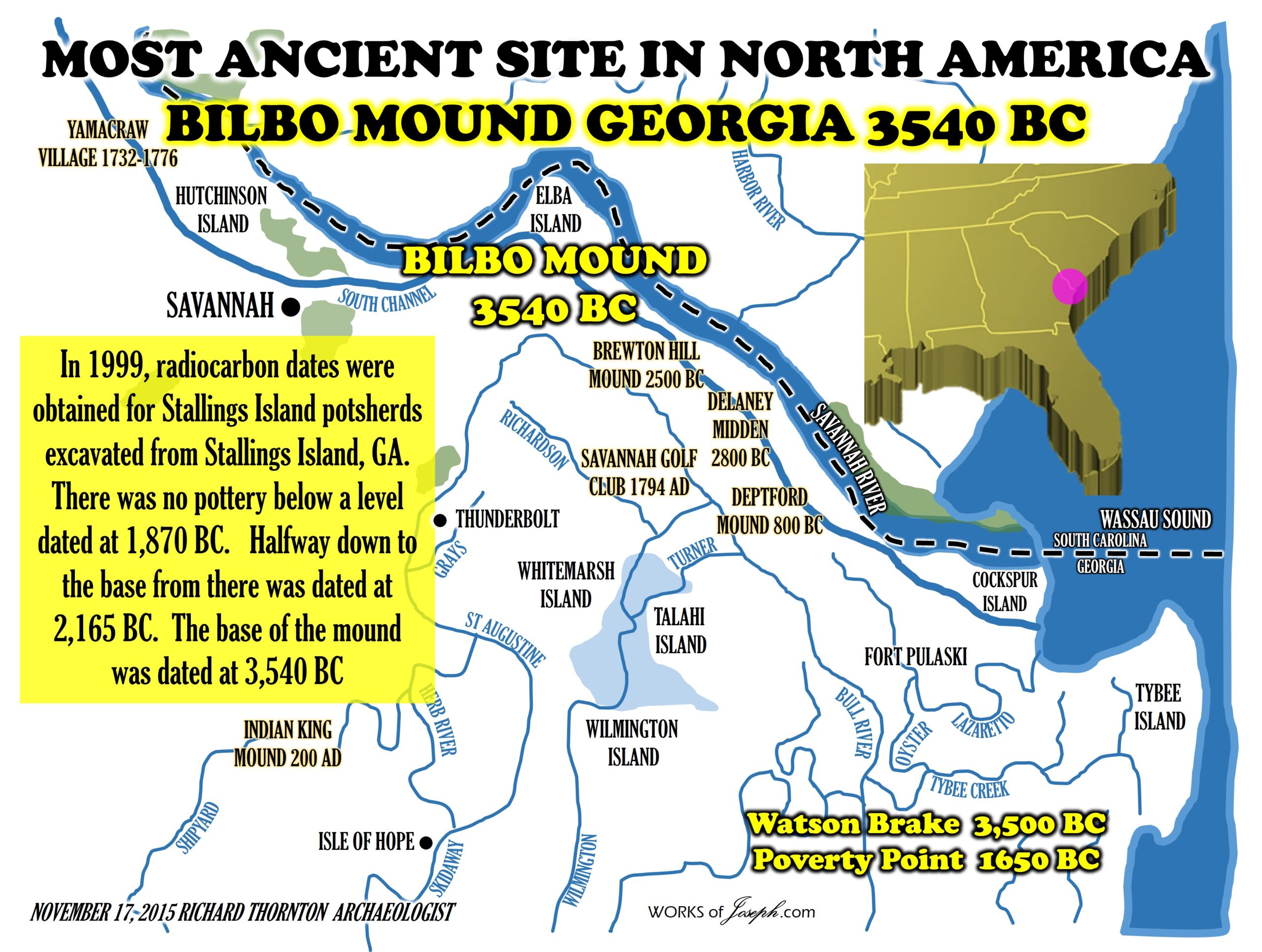

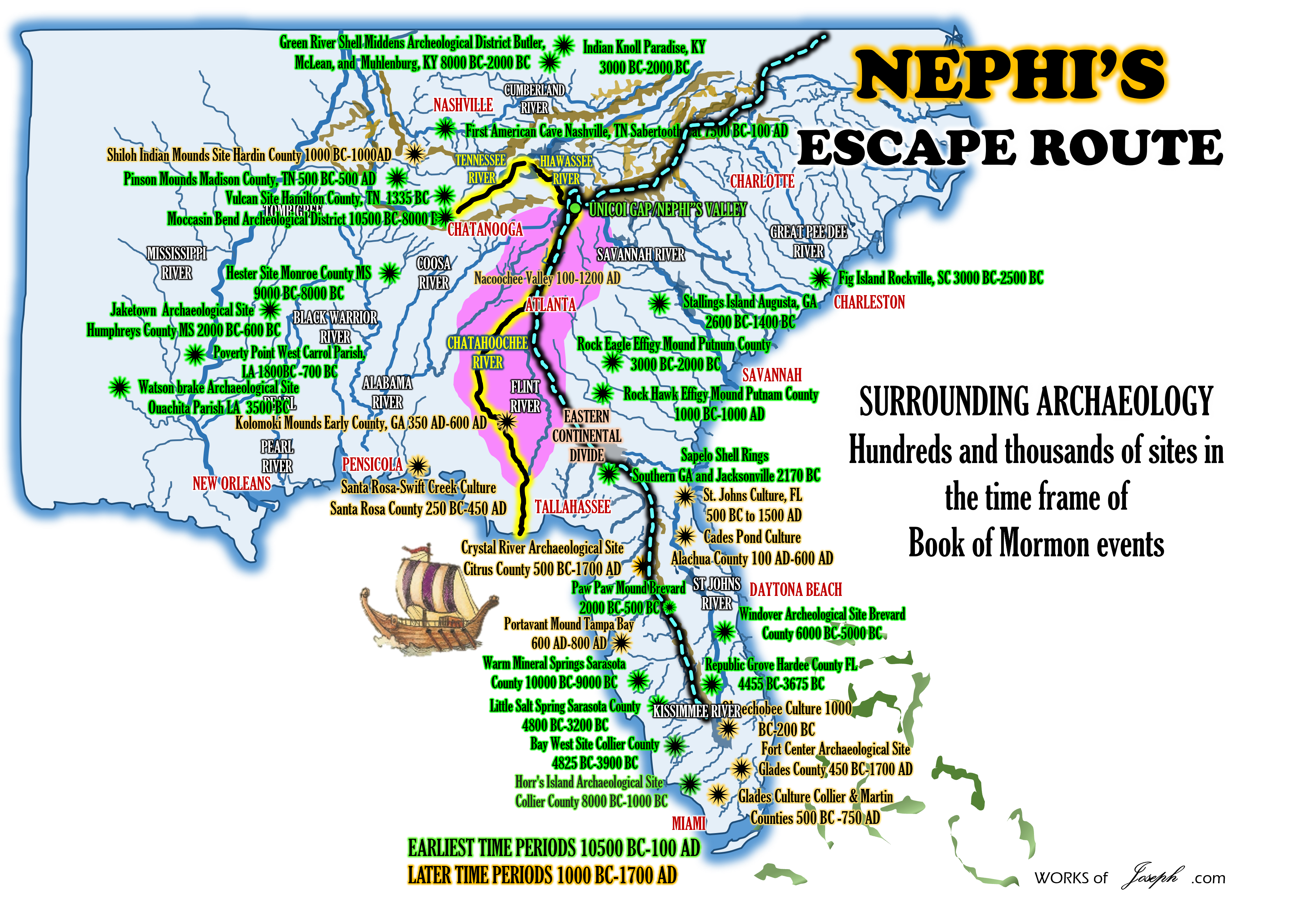

“A number of pre-Columbian cultures are collectively termed “Mound Builders”. The term does not refer to a specific people or archaeological culture, but refers to the characteristic mound earthworks erected for an extended period of more than 5,000 years. The “Mound Builder” cultures span the period of roughly 3500 BCE (the construction of Watson Brake) to the 16th century CE, including the Archaic period, Woodland period (Calusa culture, Adena and Hopewell cultures), and Mississippian period. Geographically, the cultures were present in the region of the Great Lakes, the Ohio River Valley, and the Mississippi River valley and its tributary waters.

The first mound building was an early marker of political and social complexity among the cultures in the Eastern United States. Watson Brake in Louisiana, constructed about 3500 BCE during the Middle Archaic period, is currently the oldest known and dated mound complex in North America. [Maybe it isn’t, it could be Bilbo Mound in GA,see below]. It is one of 11 mound complexes from this period found in the Lower Mississippi Valley. These cultures generally had developed hierarchical societies that had an elite. These commanded hundreds or even thousands of workers to dig up tons of earth with the hand tools available, move the soil long distances, and finally, workers to create the shape with layers of soils as directed by the builders.” Wikipedia

Bilbo Mound Savannah Georgia

Some researchers believe that the Jaredites may have come from the Near East and traveled the Atlantic and arrived up the St Lawrence River near the Great Lakes. Some believe the Jaredites traveled on foot east from the Tower of Babel across Asia and traveled the Pacific arriving at the Columbia River. With the information dating Louisiana and Georgia as places of the oldest North American known civilizations, I am beginning to consider that the Jaredites may have taken the same route to North America as Lehi near Tallahassee Florida, and/or Mulek up the Mississippi River locating near Montrose, Iowa. I believe information is so ancient as to not be very accurate in determining the correct route of the Jaredites, but it is very interesting to speculate on the plausibility of each location.

Unprecedented’ Native American burial site discovered off Florida

If you are looking for plausible evidence of the Jaredites and Nephites in North America from 3000 BC to 500 AD, you will find all sorts of information by reputable archaeologists and scientists.

DIGGING HISTORY Published February 28, 2018 By Travis Fedschun, | Fox News

Ancient Native American burial spot found off Florida coast

A Native American burial spot has been found underwater off the Florida coast. Researchers say it’s been there for 7,000 years.

A Native American burial site hidden for 7,000 years beneath the Gulf of Mexico off the coast of Florida has been unearthed in what archaeologists are calling an “unprecedented” discovery.

Florida Secretary of State, Ken Detzner, said in a news release on Wednesday the unmarked site near Venice, which measures roughly 0.75 acres, was first discovered by a diver in June 2016, who then reported possible human remains on the continental shelf to the Bureau of Archaeological Research.

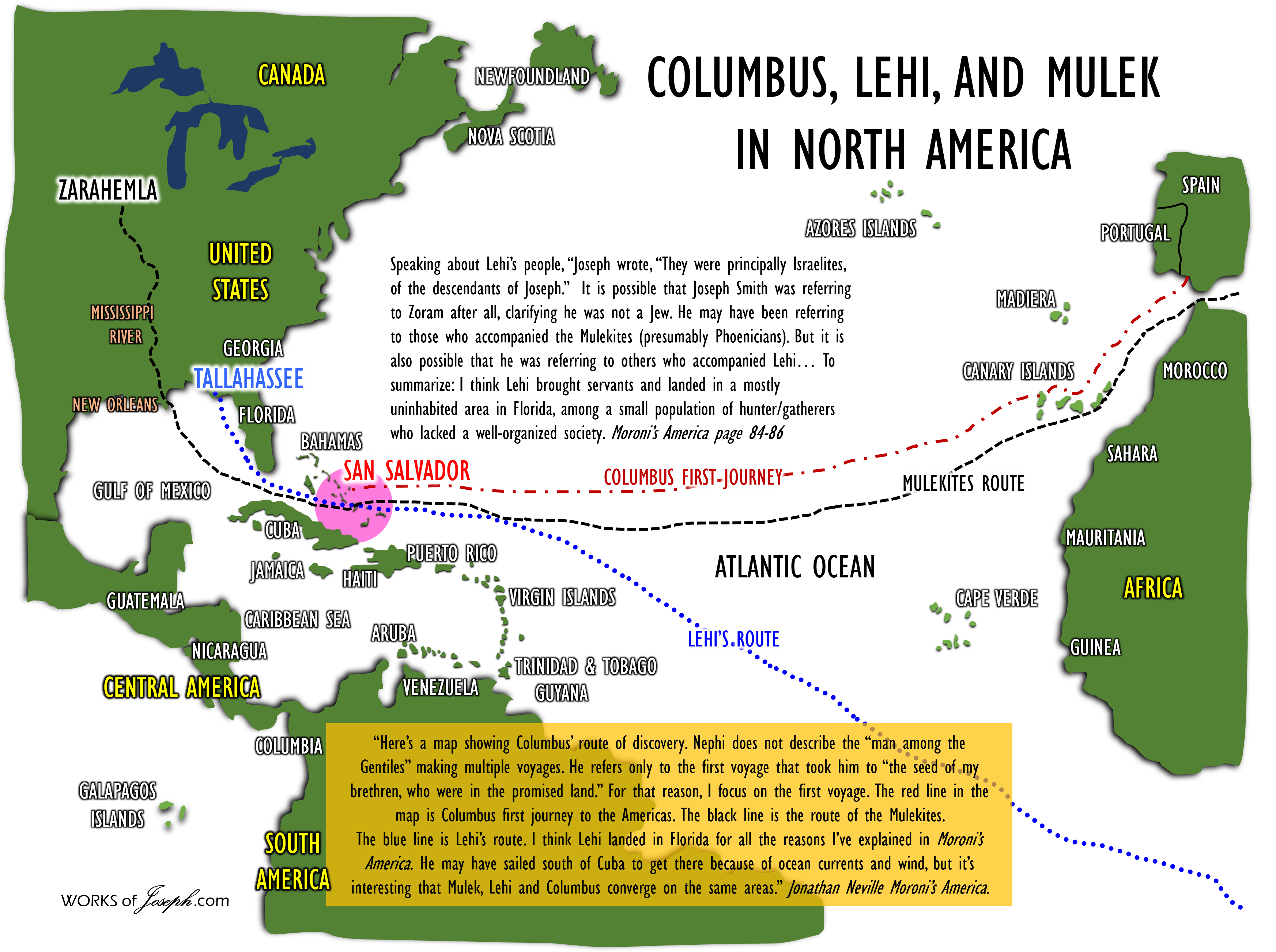

“Speaking about Lehi’s people, “Joseph wrote, “They were principally Israelites, of the descendants of Joseph.” It is possible that Joseph Smith was referring to Zoram after all, clarifying he was not a Jew. He may have been referring to those who accompanied the Mulekites (presumably Phoenicians). But it is also possible that he was referring to others who accompanied Lehi… To summarize: I think Lehi brought servants and landed in a mostly uninhabited area in Florida, among a small population of hunter/gatherers who lacked a well-organized society.” Jonathan Neville Moroni’s America page 84-86“

“Speaking about Lehi’s people, “Joseph wrote, “They were principally Israelites, of the descendants of Joseph.” It is possible that Joseph Smith was referring to Zoram after all, clarifying he was not a Jew. He may have been referring to those who accompanied the Mulekites (presumably Phoenicians). But it is also possible that he was referring to others who accompanied Lehi… To summarize: I think Lehi brought servants and landed in a mostly uninhabited area in Florida, among a small population of hunter/gatherers who lacked a well-organized society.” Jonathan Neville Moroni’s America page 84-86“

I think Lehi landed in Florida for all the reasons I’ve explained in Moroni’s America. He may have sailed south of Cuba to get there because of ocean currents and wind, but it’s interesting that Mulek, Lehi and Columbus converge on the same areas.” [Below are some reasons].” Jonathan Neville Moroni’s America.

1- Wind current routes across the Atlantic (in the fall when honey and fruits were available, and the natural currents in the fall take you west) would put them somewhere in the Caribbean. This route was proven to be possible by the Phoenicia Expedition of 2009.

2- They went where the Lord directed them with the Liahona, so I don’t think they would have just landed wherever the wind blew them (which would probably have been Hispaniola or maybe the East Coast of Florida or South Carolina).

3- I think it makes sense they landed about the same latitude [Similar climate for seeds] as Jerusalem, which they could tell from the stars.

Lattitudes Similar 30° 26′ 17″ N (Tallahassee, FL) and 31° 46′ 48″ N (Jerusalem)

Not similar 15° 30′ 0″ N (Guatemala)

4- Crops grew abundantly. This would be difficult in the jungles or islands.

5- It had to be a mostly unoccupied area (not Mesoamerica). Only small groups of hunter/gatherers in Southeastern U.S. at the time. [A large group of people wouldn’t have allowed Nephi to be their king]

6- It had to be the same general land where the Jaredites lived. [Cumorah and Ramah]

7- Should have archaeological evidence. (See Nancy White article below)

8- There should be signs of Hebrew writing or relics. (Holy Stones, Bat Creek Stones, Los Lunas, etc.)

9- Lehi and Nephi brought much honey with them from Bountiful in Oman. 1 Nephi 18:6 “And it came to pass that on the morrow, after we had prepared all things, much fruits and meat from the wilderness, and honey in abundance, and provisions according to that which the Lord had commanded us, we did go down into the ship, with all our loading and our seeds, and whatsoever thing we had brought with us, every one according to his age; wherefore, we did all go down into the ship, with our wives and our children.” It would make sense that the Lord may have led them to another land (Apalachicola FL) that had an abundance of honey producing vegetation, or Lehi may have brought the seeds from Israel to grow the White Tupelo Gum trees, nyssa ogeche, that are found naturally in Florida. Remember the Jaredites also brought bees with them to the Promised land. Ether 2:3 “And they did also carry with them deseret, which, by interpretation, is a honey bee; and thus, they did carry with them swarms of bees, and all manner of that which was upon the face of the land, seeds of every kind.”

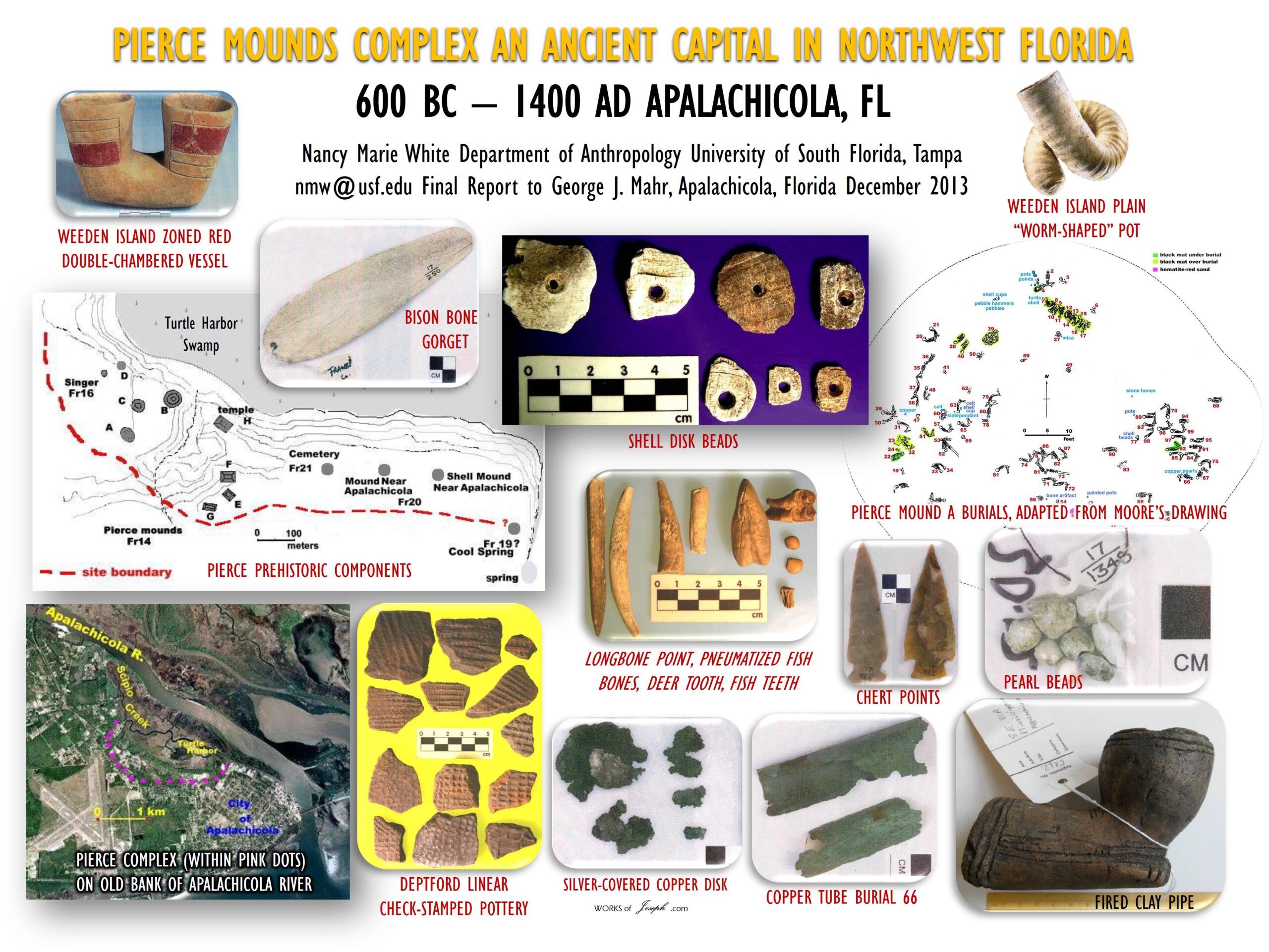

Pierce Mounds Florida

“Pierce Mounds, [600 BC to 1400 AD] at the mouth of the river (Apalachicola) and overlooking both north-south and east-west traffic, were part of a major multi-component center with remarkable Middle Woodland mounds. Materials clustered around the Apalachicola delta and coast close to Pierce and spread from there up the river. Prestige goods were possibly traded down to major mound centers then moved to other centers along the valley, ending up in burial mounds all over the valley, perhaps interred with important people during Swift Creek times, (100-800 AD) and interred in mass deposits in slightly later Weeden Island times. Such items likely were transported down the river to Pierce, where they were distributed to the inhabitants of nearby coastal mounds involved in the procurement and management end of the trade network, and then traded up the river to other trade partners. Since nearly all the mound sites documented in this thesis have both Swift Creek and Weeden Island pottery, the suggestion is also that these systems endured for a long time as ceramic styles and possibly associated archaeological cultures changed. This research should contribute to a better understanding of Middle Woodland ceremonialism in the Southeastern United States and the Apalachicola watershed, and the systems through which ceremonial artifacts moved around the land.

In the future, data from higher up the river in Georgia and Alabama could be compared to help create a picture of Middle Woodland manifestation in the entire valley for comparison with the rest of the Southeast and discussion of differences between trade routes along major waterways and overland historic trails. Further testing of the exotic materials in the mounds for trace elements or other data could shed light on trade routes along which these artifacts and raw materials were traded. With better understanding of the major and minor routes, questions regarding the role of sites in Middle Woodland exchange can be answered. Mounds like Poplar Springs Mound are facing destruction from development and looting. It is essential that these sites are studied before they are gone.

Timucua Tribe – Lost Today

The Florida peninsula in those days was twice as wide as it is today because the sea was lowered by Ice Age glaciers that locked up frozen sea water in northern areas. This exposed more dry land, making Florida wider, and by 4,000 B.C…, the Paleo-Indians were living in villages year-round along the St. Johns River. Some years later they were joined by people who spoke Timucua, and by 2,000 B.C. these Volusia residents were fashioning clay pottery made sturdy by using the plant fiber of Spanish moss.

Then 3,500 years later, the Spanish came to Florida, and they encountered these long-time settlers who spoke Timucua, the predominant language, possibly dating back to 2,000 B.C. Timucua was the “Latin” or its day, much as English is now the language used by all commercial airlines; and the heritage of the Timucua language is perpetuated today in the name Tomoka (Timucua)…

North of the Timucuans on the west of Florida were the Apalachees who lived along the Florida Gulf coast, and south of the Timucuans along the Gulf coast were the Calusas who lived west of Lake Okeechobee to Tampa Bay and also south of the bay down to Naples and likely farther. South of the Timucuans along the Atlantic coast were the Ais (Indian River), the Jeagas (Palm Beach), and the Tekestas (Miami and the Keys).” By Denny Bowden

Volusia History – Retracing Florida’s Past

Traveling through American history, destinations & legends since 2003.

by Kathy Weiser

“They be all naked and of goodly stature, mighty, faire and as well shapen…as any people in all the worlde, very gentill, curtious and of good nature… the men be of tawny color, hawke nosed and of a pleasant countenance…the women be well favored and modest…” — French explorer Jean Ribault

The Timucua were the Native American people living in the Northeast and North Central portions of Florida. Their name may derive from the Spanish pronunciation of the Timucuan word atimoqua, which means “lord” or “chief.” The Timucua probably numbered between 200,000 and 300,000 people organized into various chiefdoms speaking a common language. The earliest evidence of their presence dates from around 3000 BC.

Semi-nomadic, during the mild Fall and Winter months, the Timucua lived in the inland forests. They planted maize, beans, squash, melons, and various root vegetables as part of their diet employing “slash and burn” technology. Large growth would be cut, and then the fields would be cleared with fire. The soil would be turned and broken utilizing the nitrates in the ash as an effective fertilizer. They would also collect wild fruits and berries and bake bread made from the root starch of the koonti plant. They cultivated tobacco and utilized a communal food storage system suggesting crop surpluses.

Timucuans also hunted game, including deer, alligator, bear, turkey, and possibly eastern bison. They would migrate to the cooler seashores during the hot summers, where they would fish and collect oysters and shellfish. The evidence of their culture still exists in the many shell middens, essentially Indian trash piles, still found in Florida’s coastal areas.

The Spanish sent several expeditions through the Central Florida area during the first half of the 16th century, primarily looking for gold and other exploitable natural resources. Most of their impact fell on the Timucua. Juan Ponce de Leon landed near present St. Augustine in 1513, claiming Eastern North America for the Spanish crown and giving it the name La Florida. Later, in 1528, the Panfilo de Narvaez expedition landed at Tampa Bay and explored the western fringes of the Timucua territory. In 1539, Hernando de Soto led more than 500 men in a devastating entrada through central and north Florida. His army seized food, took women for consorts, and forced men to serve as guides and bearers. The army fought two battles with the Timucua, killing hundreds. De Soto also released hogs into the forests to breed a food supply for later expeditions; these preyed on traditional Timucuan food sources and were in turn hunted by them, further changing their habitat and lifestyle.

Spanish explorers were shocked at the size of the Timucua, well built and standing four to six inches or more above them. Perhaps adding to their perceived height was that Timucuan men would wear their hair in a bun on top of their heads. All were heavily tattooed, and such tattoos were gained by deeds, usually in hunting or war. These elaborate decorations were created by poking holes in the skin and rubbing ashes into the holes. The Timucua were dark-skinned with black hair. They wore minimal clothing woven from moss or crafted from various animal skins.

Much of what we know about early Timucuan culture comes not from the Spanish but from the French. In 1564, French Huguenots seeking refuge from persecution in France founded Fort Caroline along the St. Johns River in present-day Jacksonville. After the initial conflict, the Huguenots established friendly relations with the local natives in the area. Sketches and notes of the Timucua by Jaques le Moyne, one of the French settlers, are one of the few primary resources about these people.

The Timucua’s history changed even more dramatically after the establishment of St. Augustine in 1565 as a Spanish Presidio. Having eliminated the French settlements, the Spanish began to establish missions among the Timucuan chiefdoms. The Franciscan missionaries Christianized and Hispanized the Indians. Fortunately, through their scholarship, the friars preserved the Timucuan language, one of the few eastern tribal languages to have survived.

Timucuans Near Extinction

By 1595, contact with Europeans and the diseases they brought with them had decimated the majority of the Timucuans. By 1700, the Timucuan population had been reduced to a mere 1000. Spanish colonization, which relied on intermarriage with local populations, also absorbed many of the Timucuans into the mestizo, i.e., “mixed blood” colonial culture

British incursions during the early 18th century further reduced the Timucua. The rival European nations relied on Indian allies to fight their colonial wars. The English allied tribes, the Creek, Catawba, and Yuchi, killed and enslaved the Timucua, who were associated with the Spanish. By the end of the French and Indian War and the acquisition of Florida by Britain in 1763, there were perhaps 125 remaining. This last remnant either migrated with the Spanish colonists to Cuba or were absorbed into the Seminole population. They are now considered an extinct tribe.

More Information:

Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve

12713 Fort Caroline Road Jacksonville, Florida 32225 904-641-7155

Source: National Park Service

Compiled by Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated July 2021.

Unique Archaeological Finds Point To The Lost Indigenous Town Of Sarabay In Florida

The UNF team first found artifacts and building posts that confirmed their discovery in 2020. This summer, the team has identified four more building posts to add to the seven uncovered last year, indicating a large Indigenous structure approximately 50-60 feet in diameter, possibly the community council house. Another unique find this summer was a small, shell artifact made by Indigenous people that displays Catholic imagery.

If it is a council house, it was the center of life for a significant village of about 100 people, UNF Archaeology Lab Director Keith Ashley told the Jacksonville. [Small number of Timucuan’s but all very important].

“It’s really important,” Ashley said. “There has not been any council house or any large structure like this found in North Florida.

We would have the first Timucuan council house if this is what it turns out to be, and it lets us know what it is like right here in the center of the community and the artifacts associated with council meetings.”

This year the team has also uncovered large amounts of Indigenous pottery dating to ca 1580-1620 CE, a date range corroborated by a series of radiocarbon dates; 10 to 15 pieces of Spanish olive jar, a large type of storage vessel made in Spain, bringing the total found by the team to more than 100; about 10 pieces of Spanish majolica, a painted tableware form of pottery from Spain; parts of Colonoware pottery made by Indigenous women but the vessel forms are European (pitcher handles, mug handles, plate forms); and bone and shell tools.

Students tell they have found bone and shell tools. An estimated 10,000 small and big pieces of indigenous pottery have been found, some carbon-dated to around 1580 to 1620. Some can be traced to St. Augustine chiefdoms, indicating trade among those who lived here centuries ago.

These discoveries offer evidence of Spanish contact in this region. As reported by Jacksonville, “the piece of majolica pottery, one side glazed blue and white, is Spanish and not Native American. Its discovery in this dig site means it may have been given or traded to a member of the Mocama tribe who flourished in this area from the 1400s to early 1600s. Even more important, it was unearthed in what appears to be a 50- to 60-foot-diameter community council house in what is believed to be the Mocama village of Sarabay.”

In the late 1500s and early 1600s, French and Spanish settlers moved into Northeast Florida met members of the Mocama. That Timucua-speaking Native American chiefdom had prospered for centuries in an estimated 19,000-square-mile area, including what is now Big Talbot Island. Mocama translates to “sea,” researchers said.”

Scientists think there was a large community on the island 1,000 years ago. However, the situation changed around 1250 when people started moving around the island and mainland. Around 1450 people started to settle down and the place eventually became the comminuty we see now.

According to Jackosnville, “early French accounts in the late 1500s said the dominant chief in the Jacksonville area was Saturiwa, whose village may have been in the Mayport area. There is mention of the village of Sarabay on an island north of the St. Johns River from a Spanish priest living in San Juan del Puerto on Fort George Island in 1602. And a sea captain in 1609 mentions the islands of San Juan (Fort George Island), Santa Maria (Amelia Island) and Sarabay.

This dig is part of the UNF Archaeology Lab’s ongoing Mocama Archaeological Project that focuses on the Timucua-speaking Mocama people who lived along the Atlantic coast of northern Florida at the time of European arrival in 1562. The Mocama were among the first indigenous populations encountered by European explorers in the 1560s.” Written by Jan Bartek

Mounds all over Florida show Nephite Civilizations.