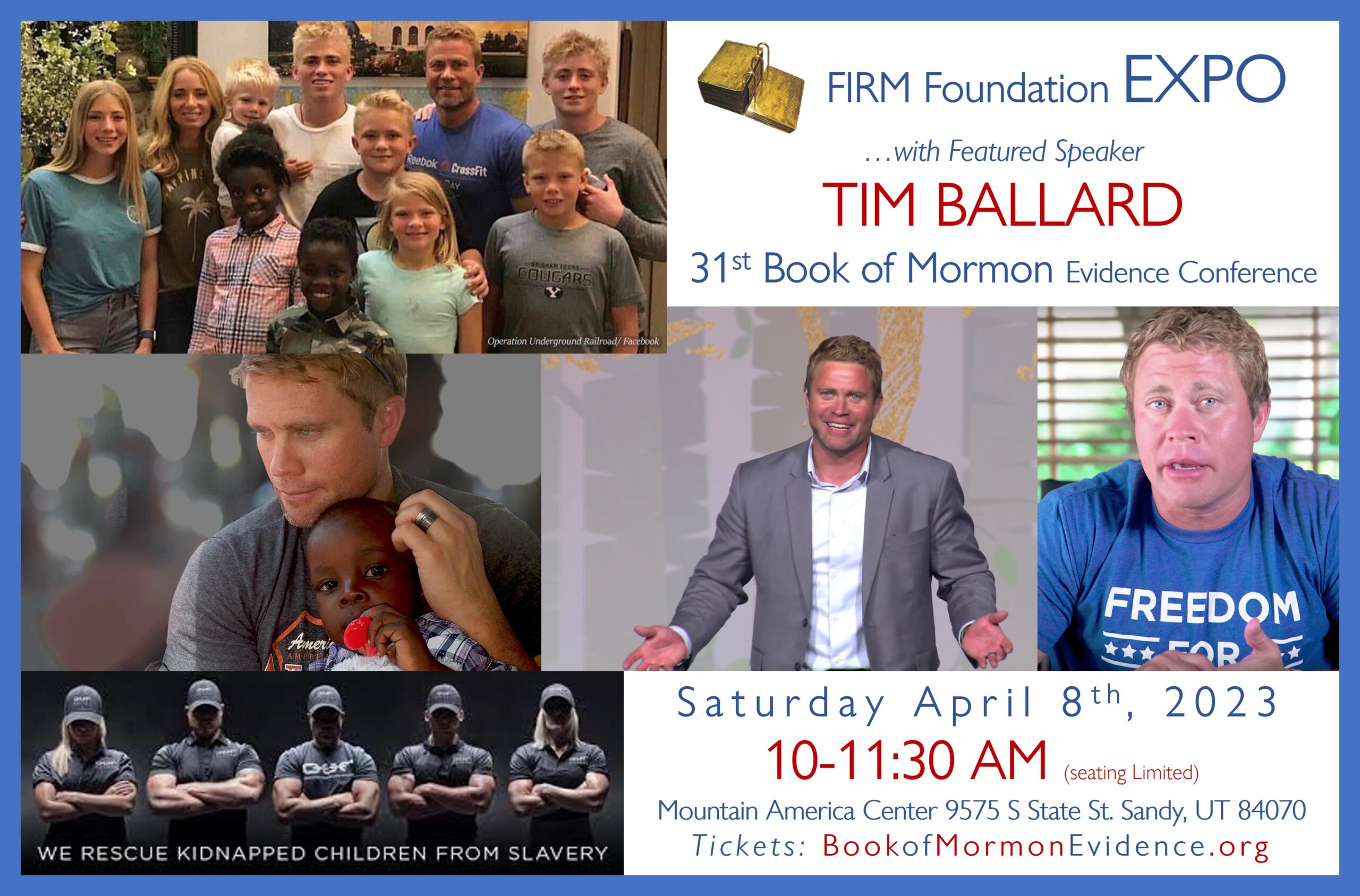

The Firm Foundation’s good friend, Tim Ballard as I’m sure you know, will be a key note speaker at our Conference again. He will speak on Saturday April 8th from 10 to 1130 am, on the subject titled, “Lincoln and the Covenant.”

Not wanting to take any thunder from his talk on Lincoln, I would like to share some amazing information about Washington on this blog. Our Founding Fathers have taken so much ridicule in the world today, it is my privledge to share all the good behind this great man, George Washington.

In a very similar vein running through the world, is a continual put-down of our wonderful Church History and the amazing Prophets of the Restoration. Satan is working overtime to destroy our past history and invalidate Prophets and Founding Fathers. Also as opposition to core beliefs and principles, many within our own Church try and destroy faith and take away from our solid traditions.

Who is Greatly Disturbed in Their Faith?

If you haven’t found physical evidence of the Book of Mormon in North America, you haven’t looked hard enough in my opinion. The Book of Mormon is true by the Spirit and I also believe the Lord has left physical evidences of that fact. Moroni said we may know the truth of all things, didn’t he?

I know for a fact and believe the Lord is in control of our nation and as long as we stay close to Him we will be blessed. I also trust His words as many in our Church today are deceived in many ways. Joseph Fielding Smith said, “Because of this theory, some members of the Church have become confused and greatly disturbed in their faith in the Book of Mormon.” Doctrines of Salvation Joseph Fielding Smith Chapter 12 [Which Theory is being referred to?]

Is There Complacency in our Church?

I also love the quote, “For it came to pass that they did deceive many with their flattering words, who were in the church, and did cause them to commit many sins” Mosiah 26:6

This is a great warning to us all. “O ye pollutions, ye hypocrites, ye teachers, who sell yourselves for that which will canker, why have ye polluted the holy church of God? Why are ye to take upon you the name of Christ? Why do ye not think that greater is the value of an endless happiness than that which never dies—because of the of the world?” Mormon 8:38

I feel strongly the above quote I have highlighted in red is speaking to we members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. I also believe we are still under condemnation at Scripture says, “And they [We Members] shall remain under this condemnation until they repent and remember the new covenant, even the Book of Mormon and the former commandments which I have given them, not only to say, but to do according to that which I have written.” D&C 84:57

by Tom Holdman (Stained glass)

Hill Cumorah Visitors Center, Palmyra, New York

(Photo courtesy of J. Stephen Conn, June 28, 2009

https://www.flickr.com/photos/jstephenconn/3699664012)

On the late evening of September 22, 1827 (1 Tishrei, 5588),

Joseph Smith Jr. obtained the golden plates

as Moroni gives him a charge to protect them.

These warnings are written to myself as to each of us, and I strive daily to repent and forgive all. I love all people whatever they feel about the geography of the Book of Mormon. I am sure they are great people and love the Lord as much as I do, but we can’t both be right. We all however, can live with the Lord again regardless.

My belief in the Heartland Theory of the Book of Mormon has greatly strengthened my overall testimony, and it may do the same for yours. If it is not important to you, I certainly understand. I report, your decide!

Why is the world and the progressives of this world working so hard to destroy our faith? Because they hate truth and want to dispel any goodness in this world. They want us to put down our Savior Jesus Christ and believe lies. Their subtleties begin often by putting little seeds of doubt into our minds. They may try and take down Joseph Smith just a bit, by distorting one little thing he spoke about. Putting just a little doubt in the proper method of translation, or advocating a climate crisis, or forcing our minds to believe a man came from an ape, it is all a tool of evil.

I want this blog to focus on a sold man of faith, even George Washington. For whatever bad you have ever heard about Washington, it is mostly lies. He is a solid man that the Lord used to begin this quest of fulfilling covenants on this the Promised Land. He and Abraham Lincoln stand out to me, as two faithful Presidents who were sent from the Lord to assist this great Nation.

George Washington: Was he ARROW and BULLET Proof?

You Decide!

George Washington and Belief in Divine Providence

This following story of the young George Washington was standard in textbooks before the modern, liberal atheists and secularists took it out, seeking to accomplish their agenda to rid our kids of patriotism, and belief in God and our Founding Fathers’ belief in God.

Bullet Proof: A Story of George Washington

The French and Indian War: Account of a British Officer July 9, 1755

The American Indian chief looked scornfully at the soldiers on the field before him. How foolish it was to fight as they did, forming their perfect battle lines out in the open, standing shoulder to shoulder in their bright red uniforms. The British soldiers—trained for European war—did not break rank, even when braves fired at them from under the safe cover of the forest. The slaughter continued for two hours. By then 1,000 of 1,459 British soldiers were killed or wounded, while only 30 of the French and Indian warriors firing at them were injured. Not only were the soldiers foolish, but their officers were just as bad. Riding on horseback, fully exposed above the men on the ground, they made perfect targets. One by one, the chief’s marksmen shot the mounted British officers until only one remained.

The American Indian chief looked scornfully at the soldiers on the field before him. How foolish it was to fight as they did, forming their perfect battle lines out in the open, standing shoulder to shoulder in their bright red uniforms. The British soldiers—trained for European war—did not break rank, even when braves fired at them from under the safe cover of the forest. The slaughter continued for two hours. By then 1,000 of 1,459 British soldiers were killed or wounded, while only 30 of the French and Indian warriors firing at them were injured. Not only were the soldiers foolish, but their officers were just as bad. Riding on horseback, fully exposed above the men on the ground, they made perfect targets. One by one, the chief’s marksmen shot the mounted British officers until only one remained.

“Quick, let your aim be certain and he dies,” the chief commanded. The warriors leveled their rifles at the last officer on horseback. Round after round was aimed at this one man. Twice the officer’s horse was shot out from under him. Twice he grabbed a horse left idle when a fellow officer had been shot down. Ten, twelve, thirteen rounds were fired by the sharpshooters. Still, the officer remained unhurt.

The native warriors stared at him in disbelief. Their rifles seldom missed their mark. The chief suddenly realized that a mighty power must be shielding this man. “Stop firing!” he commanded. “This one is under the special protection of the Great Spirit.” A brave standing nearby added, “I had seventeen clear shots at him…and after all could not bring him to the ground. This man was not born to be killed by a bullet.”

As the firing slowed, the lieutenant colonel gathered the remaining troops and led the retreat to safety. That evening, as the last of the wounded were being cared for, the officer noticed an odd tear in his coat. It was a bullet hole! He rolled up his sleeve and looked at his arm directly under the hole. There was no mark on his skin. Amazed, he took off his coat and found three more holes where bullets had passed through his coat but stopped before they reached his body.

Nine days after the battle, having heard a rumor of his own death, the young lieutenant colonel wrote his brother to confirm that he was still very much alive.

As I have heard since my arrival at this place, a circumstantial account of my death and dying speech, I take this early opportunity of contradicting the first and of assuring you that I have not as yet composed the latter. But by the all-powerful dispensations of Providence I have been protected beyond all human probability or expectation; for I had four bullets through my coat, and two horses shot under me yet escaped unhurt, although death was leveling my companions on every side of me! This battle, part of the French and Indian War, was fought on July 9, 1755, near Fort Duquesne, now the city of Pittsburgh. The twenty-three-year-old officer went on to become the commander in chief of the Continental Army and the first president of the United States. In all the years that followed in his long career, this man, George Washington, was never once wounded in battle.

Fifteen years later, in 1770, George Washington returned to the same Pennsylvania woods. A respected Indian chief, having heard that Washington was in the area, traveled a long way to meet with him.

He sat down with Washington, and face-to-face over a council fire, the chief told Washington the following:

I am a chief and ruler over my tribes. My influence extends to the waters of the great lakes and to the far blue mountains. I have traveled a long and weary path that I might see the young warrior of the great battle. It was on the day when the white man’s blood mixed with the streams of our forests that I first beheld this chief [Washington].I called to my young men and said, “Mark yon tall and daring warrior? He is not of the red-coat tribe—he hath an Indian’s wisdom and his warriors fight as we do—himself alone exposed. Quick, let your aim be certain, and he dies.”

Our rifles were leveled, rifles which, but for you, knew not how to miss—’twas all in vain, a power mightier far than we shielded you.

Seeing you were under the special guardianship of the Great Spirit, we immediately ceased to fire at you. I am old and shall soon be gathered to the great council fire of my fathers in the land of the shades, but ere I go, there is something bids me speak in the voice of prophecy:

Listen! The Great Spirit protects that man [pointing at Washington], and guides his destinies—he will become the chief of nations, and a people yet unborn will hail him as the founder of a mighty empire. I am come to pay homage to the man who is the particular favorite of Heaven, and who can never die in battle.” Source

This story of God’s divine protection and of Washington’s open gratitude could be found in virtually all school textbooks until 1934. Now few Americans have read it. Washington often recalled this dramatic event that helped shape his character and confirm God’s call on his life. Though a thousand fall at your side, though ten thousand are dying around you, these evils will not touch you. See Psalms 91

The American Covenant Vol. I – Discovery Through Revolution

by Timothy Ballard

REVIEWS:

“An absorbing read into the nature of the American Covenant, how the world’s history, with its many philosophical and religious movements, serves to inform and sometimes define the Restoration that crowns the Covenant. This book compels honest scholars to open their minds and hearts to the cumulative effect of history on the Restoration…. Rather than being some new religion revealed by an angel and taught by a prophet, Mormonism is actually the crowning achievement of a long historical record. By rereading American history in light of the Restoration, Ballard has given readers a clear path to follow in understanding just how God has guided history, resulting in the ushering in of the Dispensation of the Fullness of Times.” –Jeffrey Needle, Book Review Editor, The Association for Mormon Letters

The American Covenant Vol. II – The Constitution by Timothy Ballard

REVIEWS:

“By rereading American history in light of the Restoration, Ballard has given readers a clear path to follow in understanding just how God has guided history, resulting in the ushering in of the Dispensation of the Fullness of Times.” -Jeffrey Needle, Book Review Editor, The Association for Mormon Letters

“Tim Ballard’s The American Covenant is an inspiring and thought-provoking work that will cause Latter-day Saints to think more profoundly about their role in America’s destiny, and better understand America’s place in God’s plan. The American Covenant will stir any God-fearing patriot to reflect anew on the divine origin and destiny of this remarkable nation.” -Mayor Mike Winder, author of Presidents and Prophets: The Story of America’s Presidents and the LDS Church.

George Washington Lived in an Indian World, But His Biographies Have Erased Native People

Colin G. Calloway | an excerpt adapted from The Indian World of George Washington | Oxford University Press COPYRIGHT (c) 1977 Cambridge Theological Seminary

Telling Washington’s story without erasing the people and lands that preoccupied him leads to important new questions; like, just how consequential for American history was the first president’s addiction to land speculation?

Telling Washington’s story without erasing the people and lands that preoccupied him leads to important new questions; like, just how consequential for American history was the first president’s addiction to land speculation?

Nevertheless, Indian people and Indian country loomed large in Washington’s world. His life intersected constantly with them, and events in Native America shaped the direction his life took, even if they occurred “offstage.” Indian land dominated his thinking and his vision for the future. Indian nations challenged the growth of his nation. A thick Indian strand runs through the life of George Washington as surely as it runs through the history of early America.

Washington’s first trips westward were as a surveyor, and he looked on Indian lands with a surveyor’s eye for the rest of his life. Surveyors transformed “wilderness” that disoriented and threatened settler colonists into an ordered landscape they could understand and utilize. In colonial Virginia surveyors enjoyed status; in Indian country they met with suspicion if not outright hostility. Armed with compass, chains, and logbooks, surveyors were the outriders of an advancing settler society intent on turning Indian homelands and hunting territories into a commodity that could be measured and bounded, bought and sold, and Indians knew it. When the frontier trader Christopher Gist did some surveying near the Delaware town of Shannopin, on the southeast side of the Allegheny River, in the fall of 1750, he did so on the quiet: “I… set my Compass privately, & took the Distance across the River, for I understood it was dangerous to let a Compass be seen among these Indians.”

In reality, young Washington found himself out of his depth in a complex world of rumors, wampum belts, and tribal agendas. As events spiraled out of his control, he received a crash course in Indian diplomacy, intertribal politics, and frontier conflict under the tutelage of a formidable Seneca named Tanaghrisson.

Washington never moved west himself, but the West beckoned him and the nation he led. His long association with the region as surveyor, speculator, soldier, landowner, and politician shaped his career and his vision of America’s future tied to western development. As a young man, he pursued wealth in land and a military reputation in the West; in his later years, the West became a key to building national unity. By the end of his life, according to one of the editors of the monumental Papers of George Washington, he probably knew more than any other man in America about the frontier and its significance to the future of his country. He had also accumulated more than 45,000 acres of prime real estate in present-day Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, the Shenandoah Valley, and West Virginia. It was the West, says another of his editors, that “made the Virginia farmer lift his eyes to prospects beyond his own fields and his native Virginia”; the West that “stretched his mind” to embrace an expansive vision of a republican empire; the West that, more than anything else except the Revolutionary War, prepared him for his role as nation builder.

Washington never moved west himself, but the West beckoned him and the nation he led. His long association with the region as surveyor, speculator, soldier, landowner, and politician shaped his career and his vision of America’s future tied to western development. As a young man, he pursued wealth in land and a military reputation in the West; in his later years, the West became a key to building national unity. By the end of his life, according to one of the editors of the monumental Papers of George Washington, he probably knew more than any other man in America about the frontier and its significance to the future of his country. He had also accumulated more than 45,000 acres of prime real estate in present-day Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, the Shenandoah Valley, and West Virginia. It was the West, says another of his editors, that “made the Virginia farmer lift his eyes to prospects beyond his own fields and his native Virginia”; the West that “stretched his mind” to embrace an expansive vision of a republican empire; the West that, more than anything else except the Revolutionary War, prepared him for his role as nation builder.

Washington himself was given or assumed an Indian name, Conotocarious, meaning ‘Town Destroyer’ or ‘Devourer of Villages.’

Washington knew that the frontier was Indian country and that the future he envisioned would be realized at the expense of the people who lived there. He presided over and participated in their dispossession. He dispatched armies into Indian country; he lost an army in Indian country. The bulk of the federal budget during his presidency was spent in wars against Indians, and their affairs figured regularly and prominently in the president’s conferences with his heads of departments. He promoted policies that divested Indians of millions of acres; he sent treaty commissioners into Indian country and signed the treaties they made, even as he sometimes studiously avoided conversations about purchasing land with Indian delegates who came to the capital. His conduct of Indian affairs shaped the authority of the president in war and diplomacy. He participated in, indeed insisted on, the transformation of Indian life and culture. In the course of his life, he met many of the most prominent Native Americans of his day: Shingas, Tanaghrisson, Scarouady, Guyasuta, Attakullakulla, Bloody Fellow, Joseph Brant, Cornplanter, Red Jacket, Jean Baptiste DuCoigne, Alexander McGillivray, Little Turtle, Blue Jacket, Piominko. He also met many lesser-known individuals, who cropped up time and again in dealings between Indians and colonists, men like the Seneca messenger Aroas or Silver Heels, the Oneida-French intermediary Andrew Montour, and the Seneca Kanuksusy, who appeared in colonial negotiations under his English name, Newcastle. Having more than one name was not uncommon. Washington himself was given or assumed an Indian name, Conotocarious, meaning “Town Destroyer” or “Devourer of Villages,” and an Indian messenger who arrived at Fort Harmar in July 1788 was identified as “George Washington, a Delaware.” He was not the only Indian to bear Washington’s name.

In Washington’s administration, the process of creating the “United States” occurred “in dialogue with other nations,” including Native nations. Establishing the sovereignty of the United States required wrestling with the sovereignty of Indian nations and their place in American society. By the time Washington died, Indian power remained formidable in many areas of the continent, and American sovereignty remained contested in many spaces, but the United States had become a central presence in the world of all Indian peoples east of the Mississippi, and American expansion into Indian country was well under way. Washington, in association with men like Henry Knox, developed and articulated policies designed to divest Indians of their cultures as well as their lands and that would shape US-Indian relations for more than a century.

Washington’s paths through Indian country connected his story to indigenous peoples who told their own stories, organized and lived their lives in distinct ways, and had different visions of America and its possibilities. But theirs was not the Indian world Washington saw and knew; the Indian world he saw was the world most Americans saw. He found little to admire in Indian life. Few of its ways of living or thinking rubbed off on him. No gallery of Native American artifacts graced Mount Vernon as it did Monticello. When Washington looked at Indian country, he saw colonial space temporarily inhabited by Indian people. What he regarded as new lands were in fact quite ancient, but he showed little awareness that the ancestors of Shawnees and Cherokees had walked those lands for thousands of years before he set foot or his surveyor’s gaze on them. Jefferson was interested in the ancient petroglyphs on the banks of the Kanawha River; Washington was more interested in the extent and fertility of his lands on those riverbanks. When he looked at Indian people, he saw either actual or potential enemies or allies. They and their lands feature recurrently and prominently in Washington’s correspondence, and on occasion he expressed sympathy for Indian people. But his writings tell us little or nothing about Indians’ family life, clan affiliations, kinship networks, gender relations, languages, subsistence strategies, changing economic patterns, consensus politics, traditional religious beliefs and ceremonial cycles, distinctive Christianity, or social ethics. There was much he did not see or understand. He did not — could not — comprehend how mythic stories, clan histories, and spiritual forces shaped how Indian people perceived their world. He did not understand many of the words and sounds he heard in Indian country. Rarely if ever did he show any appreciation that the societies there functioned according to their own rules, rhythms, beliefs, and values. He demonstrated no understanding of the roles of women in Native society, beyond being farmers, and he wished to see Indian men take over that role. In all of that, he was not much different from most of his contemporaries.

A British officer traveling in the Wabash country in the 1760s was called a ‘D—d son of a b—ch’ by one Indian and given a copy of Shakespeare’s ‘Antony and Cleopatra’ by another.

By the time Washington encountered Cherokees, Iroquois, or Delawares, he met men who wore deerskin leggings and moccasins and displayed body and facial tattoos but who also often wore linen shirts and wool coats, and even the occasional three-cornered hat. He spoke with chiefs who wore armbands of trade silver and displayed European symbols of distinction like the officer’s crescent-shaped silver gorget he himself wore around his neck when he posed for his portrait by Charles Willson Peale in 1772. He would have seen women who wore calico blouses and kept their children warm with blankets of red-and-blue stroud, a durable woolen cloth produced in England’s Cotswolds. Some of the Catholic Indians Washington encountered from the St. Lawrence or the Great Lakes wore crucifixes, spoke French, and had French names. Like anyone else who spent much time on the eighteenth-century frontier, he would also have met white men who wore breechcloths, moccasins, and hunting shirts and bore facial tattoos. Constantly pressing the edges of Indian country were Scots-Irish, Anglo-American, and German settlers, the kind of people that Washington and his kind of people — Tidewater planters and gentlemen — characterized as more savage than savages. He might have seen black faces; at a time when buying and selling people was as common as buying and selling land, traders, Indian agents, army officers, and settler colonists took African slaves with them when they crossed the Appalachians. Indians also sometimes owned and trafficked in African slaves and harbored runaways. Some of the chiefs who ate dinner with Washington in New York or Philadelphia would not have been surprised to be waited on by black slaves; like Washington, they were slaveholders.

Washington sometimes spent days at a time in Indian villages. He would have seen cows, pigs, and chickens: Indians got pigs from Swedish settlers in the Delaware Valley in the seventeenth century, and Delaware people called chickens tipas, mimicking the sound Swedish settlers used to call poultry. If he entered Indian lodges he would have seen many familiar objects: brass kettles, copper pots, candles, looking glasses, awls, needles, and threads. If he shared a meal, he would have eaten indigenous food — corn, beans, squash, pumpkin, venison, elk, bear’s meat, fish, hominy cakes, berries, nuts, acorns, wild onions, maple sugar — perhaps supplemented by beef, chicken, pork, milk, apples, peaches, watermelon, turnips, peas, potatoes, honey, and many European imports that Indians had added to their diets. He might have met Indian people who had developed a taste for tea and sugar; he certainly met people with a taste for rum. He would have spoken with Native people who could speak English and who, their own languages lacking profanity, had learned to swear in it. (A British officer traveling in the Wabash country in the 1760s was called a “D—d son of a b—ch” by one Indian and given a copy of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra by another.)

Washington is the “father of the nation,” and he assumed the role of “great father” to Indian people as well. Yet the Iroquois called him “Town Destroyer,” and with justification. Washington’s dealings with Indian people and their land do him little credit, but on the other hand his achievement in creating a nation from a fragile union of states is more impressive when we appreciate the power and challenges his Indian world presented. Washington’s life, like the lives of so many of his contemporaries, was inextricably linked to Native America, a reality we have forgotten as our historical hindsight has separated Indians and early Americans so sharply, and prematurely, into winners and losers.

George Washington dominates the formative events of American nation-building like no one else. He commanded the Continental Army that secured American independence, he presided over the convention that framed the Constitution of the United States, and he was the nation’s first president, serving two terms and setting the bar by which all subsequent presidents have been measured in terms of moral character and political wisdom. Ignoring or excluding Native America from Washington’s life, like excluding it from the early history of the nation, contributes to the erasure of Indians from America’s past and America’s memory. It also diminishes our understanding of Washington and his world. Restoring Indian people and Indian lands to the story of Washington goes a long way toward restoring them to their proper place in America’s story.

With the exception of his expeditions in the Ohio Valley during the French and Indian War, the key events of Washington’s life occur in the East — Mount Vernon, Philadelphia, Yorktown. But Washington’s involvement with the West was lifelong, and he consistently looked to western land for his own personal fortune and for the nation’s future. Securing Indian country as a national resource was essential to national consolidation and expansion, and few people knew more about securing Indian land than he did.

In one of the most iconic images in American history, Washington stands resolutely in the prow of a boat facing east. Emanuel Leutze’s epic 1851 painting, Washington Crossing the Delaware, captures a pivotal moment during the War of Independence. After a string of demoralizing defeats and with the rebel army on the verge of disintegration, the Revolution faced its darkest hour. Then, on Christmas night 1776, Washington led what was left of his army in a daring and desperate attack. In the teeth of a storm, they crossed the ice-clogged Delaware River from Pennsylvania to New Jersey and roundly defeated a garrison of Hessian soldiers at Trenton. A week later, they defeated a British force at Princeton. The Revolution, for the moment, was saved, and the twin victories breathed life into a cause that had seemed lost. After he died, Washington achieved almost godlike status as the savior of the Revolution and the father of the Republic,

But the Revolution was not only a war for independence and a new political order; it was also a war for the North American continent. Washington and the emerging nation faced west as well as east. If Washington did resemble a god, he perhaps most resembled the Roman Janus. Depicted with two faces, looking in opposite directions, Janus was not “two-faced” in the modern, negative sense of the term as duplicitous. As the god of passages and transitions, beginnings and endings, he looked simultaneously to the past and to the future. As America’s god of the passage from colony to nation, Washington looked east to the past and west to the future. And when he faced west, he faced Indian country.

*Note from the Author: There is no general agreement about the appropriate collective term to apply to the indigenous peoples of North America. Although I occasionally, throughout my book, use Native, Native American, indigenous, or, as in the title, First Americans, I most often use Indians or Indian people, which was the term most commonly used at the time. In writing a book aimed at a broad readership, I have used the names for Indian nations that seem to be the most readily recognizable to the most people: Iroquois rather than Haudenosaunee; Mohawks rather than Kanienkehaka; Delawares rather than Lenni Lenapee; and Cherokee, which derives from other people’s name for them, rather than how Cherokees referred to themselves, Ani-Yunwiya, “the principal people.” Applying the same criteria to individuals necessarily involves some inconsistencies, such as Joseph Brant rather than Thayendanegea and White Eyes instead of Quequedegatha or Koquethagechton, but Attakullakulla rather than Little Carpenter and Piominko rather than Mountain Leader.

Colin G. Calloway is John Kimball Jr. 1943 Professor of History and Native American Studies at Dartmouth College. His previous books include A Scratch of the Pen and The Victory with No Name. Longreads Editor: Dana Snitzky

George Washington Letter to the Tuscarora

June 6, 2013 by Roberta Estes

The French and Indian War took place from 1754 to 1763. During this time, a significant amount of land was disputed, and fighting took place primarily in these regions and in borderlands. The Native American tribes were key players, often because they already lived in these regions, understood the lay of the land, and had been recruited through promises of their lands being returned if the French won.

The French and Indian War took place from 1754 to 1763. During this time, a significant amount of land was disputed, and fighting took place primarily in these regions and in borderlands. The Native American tribes were key players, often because they already lived in these regions, understood the lay of the land, and had been recruited through promises of their lands being returned if the French won.

We often don’t think of George Washington as a player in the French and Indian War, more often in conjunction with the Revolutionary War, but he was clearly involved. In the letter below, he wrote to the Tuscarora Indians of North Carolina asking for their support. An underscored word means I couldn’t read it clearly, or at all in some cases.

George Washington Papers, 1741-1799

To King Blount, Capt Jack and the rest of the Tuscarora Chiefs.

Brothers and Friends. This will be delivered you by our brother Tom, a warrior of the Nottoways who with others of that nation have distinguished themselves in our service this summer against our great and perfidious enemies.

The intent of this is to assure you of our real friendship and love and to confirm and strengthen that chain of friendship which has subsisted between us for so many years past….a chain like ours founded on sincere love and friendship must be strong and lasting and will I hope endure while the sun and stars give light.

Brothers you can be no strangers to the many murders and cruelties committed on our countrymen and friends by that false and faithless people the French who are constantly endeavoring to corrupt the minds of our friendly Indians and Lord have stirred up the Shawnee and Delaware with several other nations to take up the hatchet against us and at the head of many of their Indians have invaded our country, laid waste our lands, plundered our plantations, murdered defenseless women and children, burnt and destroyed wherever they came….which has enraged friends the Six Nations, Cherokees, Nottoways, Cattawbas, and all our Indian allies and prompted them to take up the hatchet in our defense against these disturbances of the common peace.

I hope Brothers you will likewise take up the hatchet against the French and their Indians as our other friends have done and send us some of your young men to protect our frontiers and go to war with us against our notiss and ambitious Frenchmen and to encourage your warriors, I promise to furnish them with arms, ammunition, clothes, provision and ever necessary for war…and the sooner you send them to our assistance the greater ___ will give us of your friendship and the better shall we be enabled to take just revenge on the cruelties.

May you live a happy prosperous people and may we act with sincere love and friendship and while rivers run and trees grow is the sincere wish of your friend and Brother.

Signed with George Washington’s signature

In confirmation of the above and in hopes of your compliance with my request…I give you this string of wampum.

http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=mgw4&fileName=gwpage030.db&recNum=411

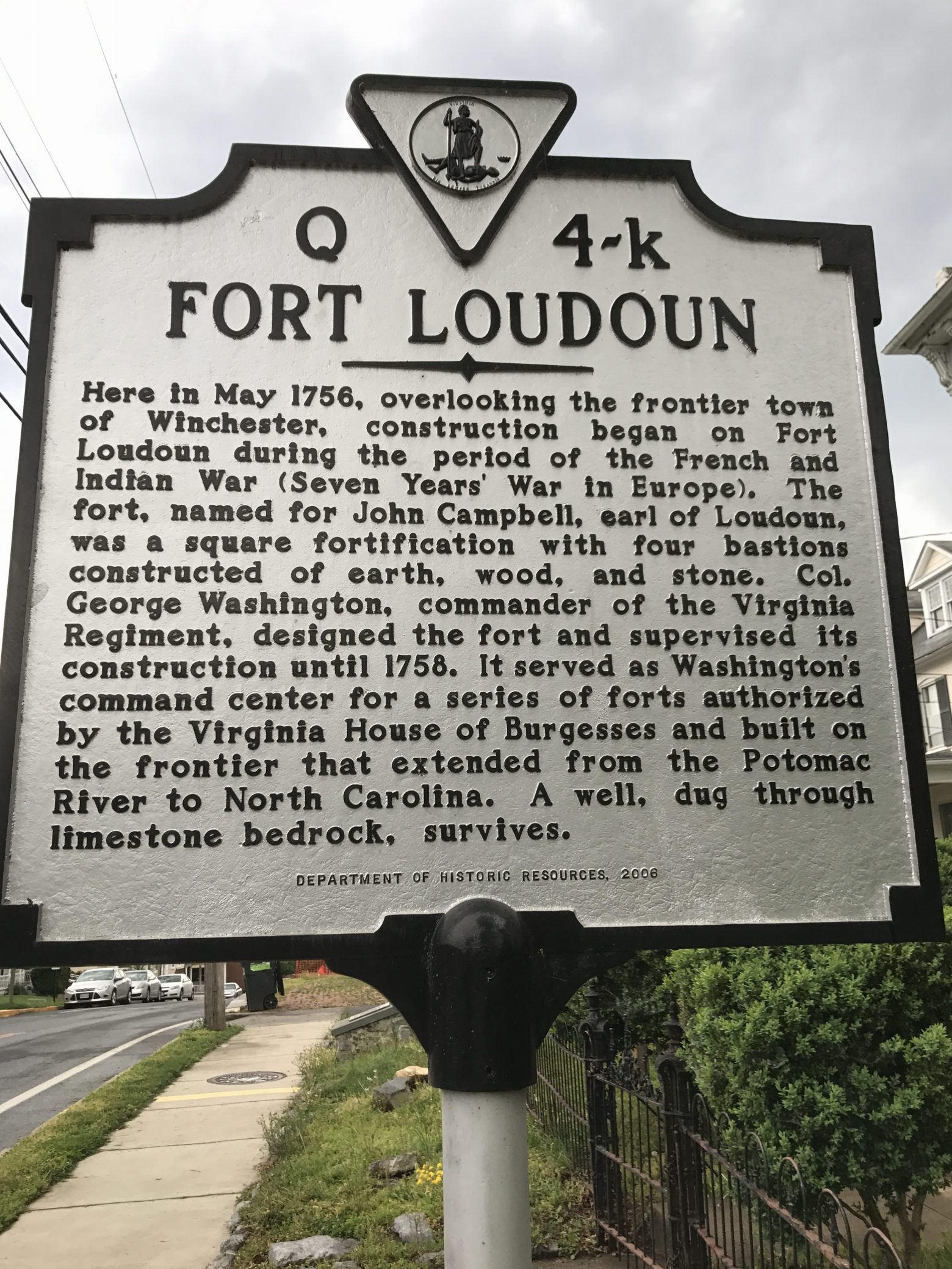

During the year of 1754. United States first president was colonel of the Virginia colonial militia, while he was colonel he headed a project to build fort London in Winchestor Virginia.

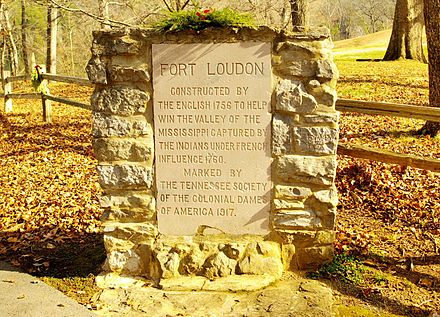

During the French and Indian War, Colonel George Washington designed and supervised the construction of a fort in Winchester, Virginia. Named Fort Loudoun, after John Campbell, the fourth Earl of Loudoun and Commander-in-Chief of British forces in North America, the fort was constructed to protect citizens from attack and served as a headquarters for Washington and his militia.

During the French and Indian War, Colonel George Washington designed and supervised the construction of a fort in Winchester, Virginia. Named Fort Loudoun, after John Campbell, the fourth Earl of Loudoun and Commander-in-Chief of British forces in North America, the fort was constructed to protect citizens from attack and served as a headquarters for Washington and his militia.

During excavation for the fort’s foundation, Washington’s men dug up skeletons—skeletons which measured seven feet in length.

The first written report of such large Indians dates back to 1707, when Swiss explorer Louis Michelle visited the Shenandoah Valley. Local Indians who lived or hunted in the Winchester area, showed Michelle huge stones, thought to be sacrificial altars. He was also shown burial mounds of ancient warriors known to have been over seven feet tall. Michelle’s diaries and maps relating to his adventures in the Shenandoah Valley are currently stored in the Royal Archives in London.

A monument that mentions the Indian grave site is located in Virginia but the artifacts and skeletons have not been seen since.

A monument that mentions the Indian grave site is located in Virginia but the artifacts and skeletons have not been seen since.

George Washington an Honest Man

George Washington was an American politician and soldier who served as the first President of the United States from 1789 to 1797 and was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. He served as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, and later presided over the 1787 convention that drafted the United States Constitution. He is popularly considered the driving force behind the nation’s establishment and came to be known as the “father of the country,” both during his lifetime and to this day.

During the year of 1754. United States first president was colonel of the Virginia colonial militia, while he was colonel he headed a project to build fort London in Winchestor Virginia.

During the French and Indian War, Colonel George Washington designed and supervised the construction of a fort in Winchester, Virginia. Named Fort Loudoun, after John Campbell, the fourth Earl of Loudoun and Commander-in-Chief of British forces in North America, the fort was constructed to protect citizens from attack and served as a headquarters for Washington and his militia.

During excavation for the fort’s foundation, Washington’s men dug up skeletons—skeletons which measured seven feet in length.

The first written report of such large Indians dates back to 1707, when Swiss explorer Louis Michelle visited the Shenandoah Valley. Local Indians who lived or hunted in the Winchester area, showed Michelle huge stones, thought to be sacrificial altars. He was also shown burial mounds of ancient warriors known to have been over seven feet tall. Michelle’s diaries and maps relating to his adventures in the Shenandoah Valley are currently stored in the Royal Archives in London.

A monument that mentions the Indian grave site is located in Virginia but the artifacts and skeletons have not been seen since.

George Washington and the Cherry Tree

George Washington is known for telling the truth. What was once taught as an eyewitness account of young Washington’s “honesty” has been pushed into the fable section by deconstructionists. Here is one account of Washington’s honesty: “One day, in the garden, where he often amused himself hacking his mother’s pea-sticks, he unluckily tried the edge of his hatchet on the body of a beautiful young English cherry-tree, which he barked so terribly, that I don’t believe the tree ever got the better of it. The next morning the old gentleman finding out what had befallen his tree, which, by the by, was a great favourite, came into the house, and with much warmth asked for the mischievous author, declaring at the same time, that he would not have taken five guineas for his tree. Nobody could tell him any thing about it. Presently George and his hatchet made their appearance. George, said his father, do you know who killed that beautiful little cherry-tree yonder in the garden? This was a tough question; and George staggered under it for a moment; but quickly recovered himself: and looking at his father, with the sweet face of youth brightened with the inexpressible charm of all-conquering truth, he bravely cried out, “I can’t tell a lie, Pa; you know I can’t tell a lie. I did cut it with my hatchet.”–Run to my arms, you dearest boy, cried his father in transports, run to my arms; glad am I, George, that you killed my tree; for you have paid me for it a thousand fold. Such an act of heroism in my son, is more worth than a thousand trees, though blossomed with silver, and their fruits of purest gold.” Story by Mason Locke Weems, 1809

George Washington “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen”