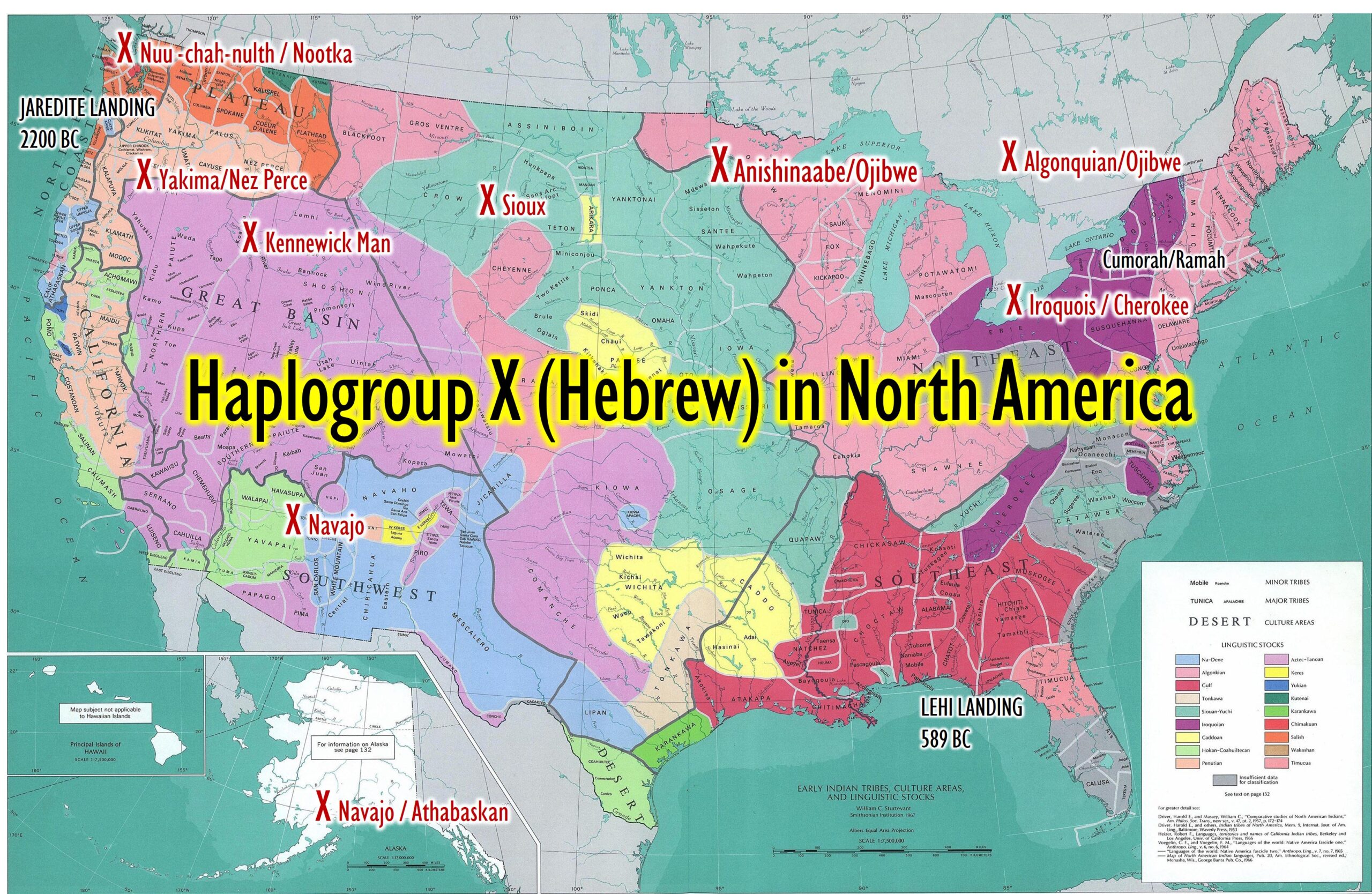

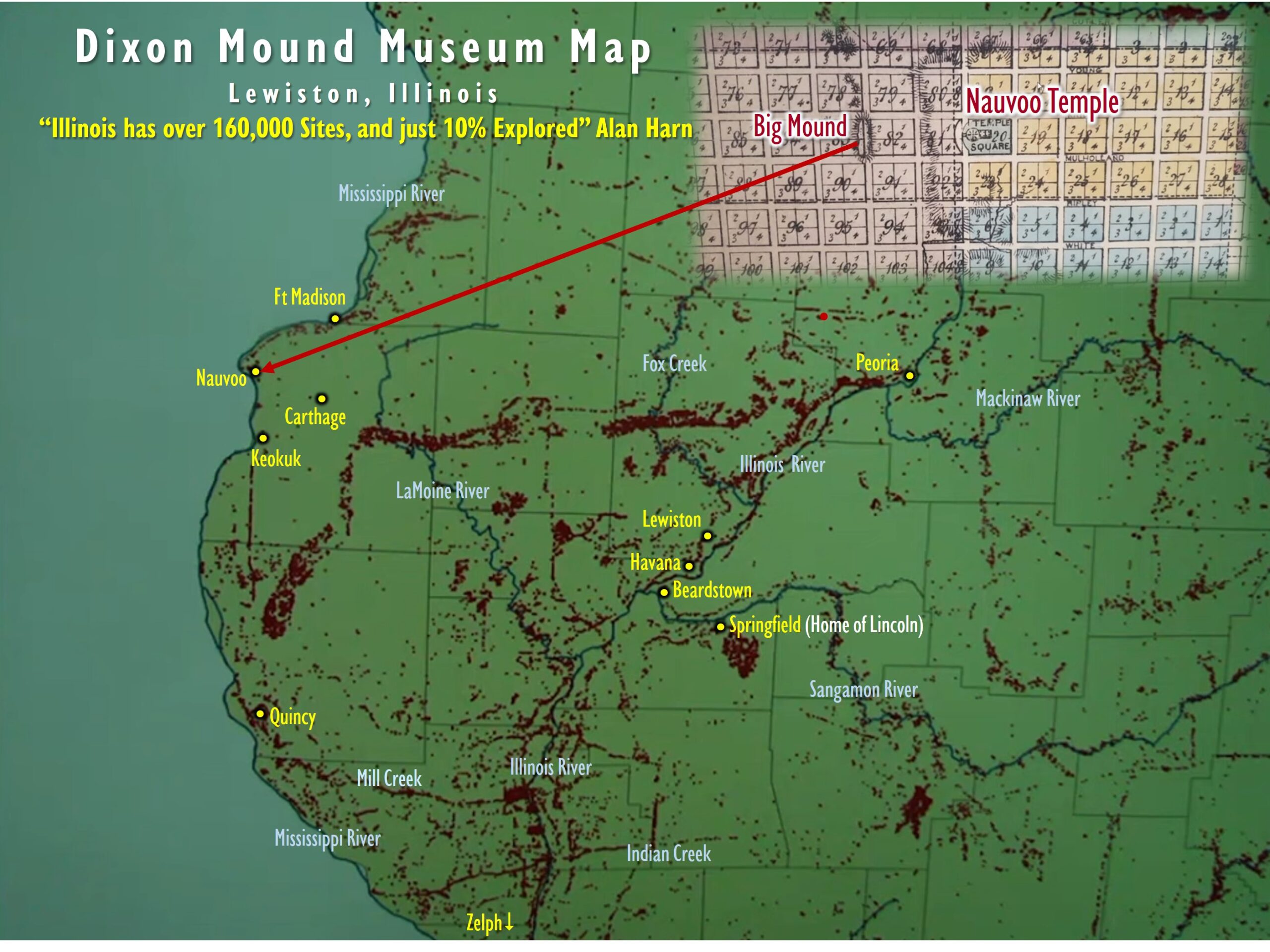

There are many connections between the ancient People of Judah and the Native Americans of North America. DNA has been found that matches the Jews of Israel with the DNA of Great Lake Tribes east of the Mississippi. The Yuchi Tribe is one of those.

The Yuchi Indians find the area around Chattanooga, Tennessee to be their homeland. The Heartland Model suggest the same area is where the Nephites lived after being chased from Florida by Laman and Lemuel. The Cherokee lived in that same area and were at war with the Yuchi. Some of the descendants of the Nephites could very well be the Yuchi or the Cherokee.

Old World Roots of the Cherokee by Donald Yates (Book)

One of the most important non-LDS books which supports the Heartland Book of Mormon geography! Old World Roots of the Cherokee: How DNA, Ancient Alphabets and Religion Explain the Origins of America’s Largest Indian Nation, by Dr. Donald N. Yates provides the most stunning new research validating the Heartland Model. The Cherokee share DNA and cultural similarities with ancient Jewish populations. This blockbuster book is critical for the true “remnant” of the Book of Mormon

“Great Surprise”—Native Americans Have West Eurasian Origins. Oldest human genome reveals less of an East Asian ancestry than thought. National Geographic

We need to look no further than the scriptures to know the Lamanites ARE DESCENDANTS of the JEWS.

11 “And again, I command thee that thou shalt not covet thine own property, but impart it freely to the printing of the Book of Mormon, which contains the truth and the word of God—Which is my word to the Gentile, that soon it may go to the Jew, of whom the Lamanites are a remnant, that they may believe the gospel, and look not for a Messiah to come who has already come.” D&C 29:26-27

12 “Which is my word to the Gentile, that soon it may go to the Jew, of whom the Lamanites are a remnant, that they may believe the gospel, and look not for a Messiah to come who has already come.” D&C 19:27

13 “And then shall the remnant of our seed know concerning us, how that we came out from Jerusalem, and that they are descendants of the Jews.”

2 Nephi 30:4

“As I read the Book of Mormon, it seemed to me that it was about my American Indian ancestors. It tells the story of a people, a part of which were later described as “Lamanites,” who migrated from Jerusalem to a “land of promise” (1 Nephi 2:20) about 600 B.C.” Larry Echo Hawk, “Come Unto Me, O Ye House of Israel,” Ensign, [Nov. 2012].

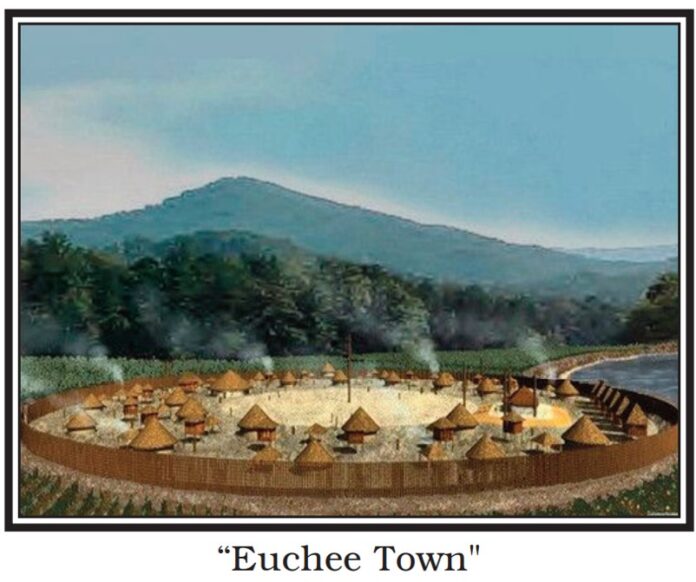

Yuchi Tribe

The Yuchi Indians are a North American Indian tribe belonging to the Southeastern Indian cultural group. Ethnohistorians indicate that during the historic period there were three principal bands of Yuchi: one on the Tennessee River, one in west Florida, and one on the Savannah River. The last of these relocated to the Chattahoochee River around 1715 and became part of the Creek Confederacy. The combined populations of all three groups probably never exceeded 3,000-5,000 persons. Unfortunately, frequent changes in location and confusion over the names applied to the tribe limits information regarding their inhabitancy of Tennessee.

The most outstanding hallmark of the Yuchis is their language, Uchean, which is distinct from all other Native American languages. While a linguistic isolate, Uchean does bear some structural resemblances to the Muskhogean and Siouan linguistic families and has occasionally been misclassified as Algonquian. Because Uchean was a difficult language to speak, most early historical sources refer to the Yuchis using a variety of non-Uchean names, including Hogologue, Tahogale, Chiska, Westo, Rickohockan, and Tamahaita.

The Yuchis referred to themselves as Tsoyahá, meaning “children of the sun.” The term Yuchi probably derives from a reply yú tcí, meaning “at a distance / sitting down,” to a standard southeastern Indian salutation: “Where do you come from?”…

In general, the social customs and lifeways of the Yuchi are similar to other southeastern Indians. They relied on intensive hoe agriculture of corn, beans, and squash, and hunting of white-tailed deer, bear, and elk. Before 1715 the Yuchis lived in permanent towns which were considered either red (war) or white (peace). Each town typically contained a square ground, a hot house, and a ball field, as well as one-room domestic structures. The square ground was the focus of male daily life, and it surrounded the sacred fire. The Busk, or Green Corn Ceremony, was the ceremonial focus of the year….

The Yuchis likely moved up the Tennessee River in the first decade of the eighteenth century, and by 1712 the South Carolina board of Indian trade affairs noted the presence of “Uche or Round Town people” among the Cherokees. Their town was known as Chestua and was probably located near the mouth of the Hiwassee River. The Cherokees referred to this Yuchi town as Tsistu’yi, or “Rabbit place.”… Tennessee Encyclopedia

Yuchi Towns

“Euchee Town” (also called Uche Town), a large settlement on the Chattahoochee River, was documented from the middle to late 18th century. It was located near Euchee (or Uche) Creek, about ten miles downriver from the Muscogee Creek settlement of Coweta Old Town. The naturalist William Bartram visited Euchee Town in 1778. In his letters he ranked it as the largest and most compact Indian town he had ever encountered, with large, well-built houses. US Indian agent Benjamin Hawkins also visited the town and described the Yuchi as “more orderly and industrious” than the other tribes of the Creek Confederacy. The Yuchi began to move on, some into the Florida panhandle

Unexpected Connection: Leviticus, O.T.

“A harvest festival comparison tradition with the Old Testament has revealed remarkable similarity. Native festivals such as their harvest celebration gave cause for early colonials to suspect a tie to the lost tribes of Israel. The connection to the lost tribes is unlikely yet a Hebrew presence within North America is very favorable. Old Testament Leviticus is compared to Yuchi tradition.”

Yuchi Harvest Festival: A Comparison

“It is their [the Yuchis’] agricultural festival that is so amazing, for it is described in detail in the Bible — in the 23rd chapter of Leviticus. [Dr. Joe] Mahan points out that there are far too many resemblances for this to be accident or shear coincidence.

This is the Feast of Booths (Tabernacles or Succoth), which includes

(1) an eight-day festival

(2) that starts on the 15th day or full moon of the holy harvest month,

(3) living in ‘booths’ throughout the festival

(4) at the religious center of the tribe, and

(5) maintaining a sacred fire.

The first three of these same observances are carried on by some Jews to this very day. The Yuchis make a pilgrimage to their religious center on the 15th day of their harvest month. During the 8-day festival, they live in ‘booths’ that have open spaces in the roofs, and are covered with foliage and tree branches. There is a sacred area in which a fire is kept burning, and they celebrate by walking around the fire in a circle. Two, large, decorated branches are carried by two men during the circling walk, and other men during other parts of the observance shake similar branches. During identical time periods, Jews today who celebrate this festival dwell in booths open to the sky, but covered with fruits, vegetables and foliage. They take circular walks or ‘circumambulations’, and plants tied together into a staff are used for ceremonial shaking. Although the Jewish celebration of Tabernacles no longer has the sacred fire, it is referred to in Leviticus.” Vincent H. Gaddis, “Native American Myths and Mysteries”, CA: Borderland Sciences, 1991, pages 73, 74 Ancient American Magazine

Leviticus 23

34 Speak unto the children of Israel, saying, The fifteenth day of this seventh month shall be the feast of tabernacles for seven days unto the Lord.

35 On the first day shall be an holy convocation: ye shall do no servile work therein.

36 Seven days ye shall offer an offering made by fire unto the Lord: on the eighth day shall be an holy convocation unto you; and ye shall offer an offering made by fire unto the Lord: it is a solemn assembly; and ye shall do no servile work therein.

37 These are the feasts of the Lord, which ye shall proclaim to be holy convocations, to offer an offering made by fire unto the Lord, a burnt offering, and a meat offering, a sacrifice, and drink offerings, every thing upon his day:

38 Beside the sabbaths of the Lord, and beside your gifts, and beside all your vows, and beside all your freewill offerings, which ye give unto the Lord.

39 Also in the fifteenth day of the seventh month, when ye have gathered in the fruit of the land, ye shall keep a feast unto the Lord seven days: on the first day shall be a sabbath, and on the eighth day shall be a sabbath.

40 And ye shall take you on the first day the boughs of goodly trees, branches of palm trees, and the boughs of thick trees, and willows of the brook; and ye shall rejoice before the Lord your God seven days.

41 And ye shall keep it a feast unto the Lord seven days in the year. It shall be a statute for ever in your generations: ye shall celebrate it in the seventh month.

42 Ye shall dwell in booths seven days; all that are Israelites born shall dwell in booths:

43 That your generations may know that I made the children of Israel to dwell in booths, when I brought them out of the land of Egypt: I am the Lord your God.

44 And Moses declared unto the children of Israel the feasts of the Lord.

Yuchi Ceremonies

There is a great significance of community ceremonies for the Yuchis today. For many Yuchis, traditional rituals remain important to their identity, and they feel an obligation to perform and renew them each year at one of three ceremonial grounds, called “Big Houses.” The Big House acts as a periodic gathering place for the Yuchis, their Creator, and their ancestors. There most important rituals are the Stomp Dance, the Green Corn Ceremony, and the Soup Dance.

Green Corn Dance

The Green Corn Festival (also called Green Corn Dance or Ceremony) is a Native American celebration and religious ceremony. The dance is held by the Creek, Cherokee, Seminole, Yuchi, and Iroquois Indians as well as other Native American tribes. The festival typically lasts for three days for all tribes and includes numerous different activities that vary from tribe to tribe. For example, the Yuchi tribe celebration begins in late April and early May and last until about the third week of July. The opening day of the ceremony varies across tribes depending when the corn is ripe. This can be any time from May to October and is determined by the “Keepers of the Faith.” Corn is not to be eaten until the Great Spirit has been given his proper thanks.

During the festival, members of the tribe give thanks for the corn, rain, sun, and a good harvest. The thanksgiving is sacred to the Indians. Folk tales are popular telling what happens when thanks is not given. Some tribes even believe that they were made from corn by the Great Spirits.

The Green Corn Festival is also a religious renewal . Members of the tribe join at a religious gathering and stand with heads bent to show reverence. (Indians never kneel.) After a minute a prayer is said (see Appendix A for a copy of the prayer). In between the thanksgivings is the Great Feather Dance. Depending on the tribe women, may or may not be included in this dance.

Although it is not part of the ceremonial purpose of the Green Corn Dance, council meetings are also seen during the dance and festival. With the exceptions of murder and infractions of marriage rules, the old year’s minor problems are forgiven at the council meetings. Youth who have come of age and babies are given their names. This is a distinct part of Indian life.

The ball game is included in the festival. It is played at different times and the rules vary depending on the tribe. The Yuchi tribe plays a tournament in the early spring (see Appendix B for the Yuchi Tribe’s annual calendar). The Iroquois tribes throw a ball at a pole to see who can throw it the highest. The Yuchi tribes have teams (boys against girls) that try to get the ball into baskets at opposite ends of a field. The Yuchi tribe has four tournament games beginning in April and lasting for four weekends. In the Yuchi tribe the boys throw and catch the ball but may not run with the ball. The girls may run with the ball as well as catch and throw the ball in order to get it into the basket.

Another part of the religious ceremony is the busk. The word busk comes from the word boskita and means to fast. The Creek New Year is marked with this part of the ceremony. At this time, members of the tribe clean out homes, throw out ashes, and buy or make new clothes. All the “filth” and broken items from the tribe are put into one common heap and burned. It is an outward sign of the inward renewal to their religion.

The “Black Drink” is also a way the Indians cleanse themselves and is another sign of renewal. The drink causes vomiting. It purifies participants from minor sins and leaves them in a state of perfect innocence. It also give them courage to be daring during war and strength to keep friendships.

At the end of every day, the people feast. Everyone can participate and enjoy the food and good harvest. Slabs of beef, corn soup, beans, squash are eaten. The tribes celebrate a good harvest and eat many different meals made from corn: tortillas, corn meal, corn bread, corn soup, and others as well.

The Green Corn Festival varies across tribes. This makes it difficult to give you all the information you will need to teach a well thought out unit. However, as I read the overriding theme of diversity and respect was evident. Although the Natives Americans traditions varied they still had respect and gratitude for what they had been blessed with in their lives.

Stomp Dancing

Stomp dancing is an important aspect of Yuchi culture. Historically, stomp dancing has its roots in the Green Corn Ceremony, springtime celebrating harvest, redemption and forgiveness. Men sing stomp dance songs in a call-and-answer format, following a male song leader, who often sets the dance rhythm using a handheld turtle shell rattle.

Women enhance the rhythms with shakers made from box turtle shells worn on their legs. The use of turtle shells is intended to show respect and gratitude to the animal world for providing so many good things for the people.

Yuchi’s believe that the fire at the center of the dance circle is the embodiment of Aba’ Binni’li’ (the Creator) on earth and that the smoke carries our prayers to the Creator. Stomp dancers move counterclockwise around the fire, so their hearts are closest to the fire, and the smoke lifts their prayers to Aba’ Binni’li’.

Soup Dance

Yuchi ceremonial life that are unique. He thus argues for their recognition as a group that is distinct from the Creek, with whom they have been identified for over two hundred years. What is unique for them often is not any substantive differences in content or meaning from that of Creek, Shawnee, or other Woodlands cultures, but in how ceremonial life is “configured” there. For example, the Yuchi Soup Dance, Iroquois Dead Feast, and Shawnee Ghost Feast all share several overarching themes, including the assemblage of ancestors, divisions between male and female roles, and a mood of “dignified gaiety” (p. 258). However, these rites are performed in substantively different configurations. These configurations should not be dismissed as irrelevant, and Jackson provides ample evidence that they result in shifts of primary significance for ritual performance. In the example above, the focus for the Yuchi rests on the communally shared responsibility of the living for maintaining connection with the dead; other tribes’ rites may focus on familial rather than communally shared responsibilities, or they may even shift focus more dramatically to the gendered exchange of food.