In year 16-18 AD, Lachoneus gathered all the people to the center of the land. 3 Nep 3:21-24. We believe the center of the land to be at the southern tip of Illinois. There is perfect protection with the Mississippi River on the west and the Ohio River or the Wabash River on the East. In the tip of Illinois is an escarpment and remains of old fortifications and walls all the way across. The article below talks all about those stone walls and fortifications of southern Illinois.

It’s an interesting observation that the designated land went “to the line which was between the land Bountiful and the land Desolation.” It makes sense for Lachoneus to use this as a border; he wouldn’t want to be subject to attack from the north, and that land (Desolation) was considered cursed. Moroni’s America page 221 9

It’s an interesting observation that the designated land went “to the line which was between the land Bountiful and the land Desolation.” It makes sense for Lachoneus to use this as a border; he wouldn’t want to be subject to attack from the north, and that land (Desolation) was considered cursed. Moroni’s America page 221 9“But Gidgiddoni saith unto them: The Lord forbid; for if we should go up against them the Lord would deliver us into their hands; therefore we will prepare ourselves in the center of our lands, and we will gather all our armies together, and we will not go against them, but we will wait till they shall come against us; therefore as the Lord liveth, if we do this he will deliver them into our hands.”

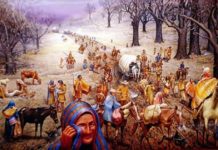

And it came to pass in the seventeenth year, in the latter end of the year, the proclamation of Lachoneus had gone forth throughout all the face of the land, and they had taken their horses, and their chariots, and their cattle, and all their flocks, and their herds, and their grain, and all their substance, and did march forth by thousands and by tens of thousands, until they had all gone forth to the place which had been appointed that they should gather themselves together, to defend themselves against their enemies.

And the land which was appointed was the land of Zarahemla, and the land which was between the land Zarahemla and the land Bountiful, yea, to the line which was between the land Bountiful and the land Desolation. 3 Nephi 3:21-23

Ancient American • Issue Number 50; Article below is by Wayne May

In southern Illinois, down at the tip, there is archaeological evidence revealing a fortification project of massive undertaking. Ancient people of times gone by, constructed fortified hilltops of earth, stone and wood. These stretch from the Ohio River on the east to the Mississippi River on the west. Every hilltop could have possibly seen one fort/wall to the left and one fort/wall to the right. Signals could be passed along the fortified hilltops very fast in the event of an approaching enemy or just to announce some event. The overall distance for this line of defense is approximately 100 miles in length as a crow flies.

At least 14 pre-Columbian stone structures are known to exist in the hills of southern Illinois. There may be others… walls of which most have been taken down to ground level. In fact, the latest find was made when the foundation courses were accidentally observed, two miles east of Makanda, IL.

These walled structures, forming a rough alignment across the southern tip of Illinois between the Mississippi and Ohio rivers have one striking feature in common. Each is located on top of a high bluff that projects outward. From the rear, they can be approached easily over gently sloping ground; and it is across this approach that the walls are built. On every other side, the structures border on sheer cliffs. This would suggest that their primary purpose was defensive. However, only one (near Stonefort in southern Saline County) has a water supply within it. Stone cairns and stone-lined pits are found beside the entrance gateways of many of the enclosures. They are constructed of drystone masonry, using loose stones of moderate size, mainly from the beds of the brooks flowing along the cliff bottoms. Early records, and the recollections of very old people, indicate that the walls were originally six to ten feet high and about as wide.

Puzzling Artifacts, page 59, published by the Source Book Project, William Corliss

They are now greatly diminished, due to farmers hauling away stones from them. Some, such as the one near Stonefort already referred to, were over 600 feet in length. The amount of labor necessary to build such walls, of stones that had to be carried up from the brook beds 200 feet below, is staggering.

The wall at the Stonefort structure forms half of an accurate ellipse with axis of 450 and 190 feet. It is not easy to see how it could have been so accurately laid out, if the area were as heavily forested at the time as it is now.

The stone walls stretch from the Mississippi River to the Ohio River, as though forming a broken, staggered line south of Carbondale, Marion, and Harrisburg, the three cities of the region, and separating off the southern tip of Illinois. The locations of nine of the walls have been positively identified, and doubtless more were destroyed to make way for modern development or are yet to be uncovered in the thickly overgrown areas of the Shawnee National Forest. One of the more recent examples was found in 1970, in Giant City State Park near Makanda, IL.

The Lewis Wall, at Makanda, is virtually identical to its counterparts. Mr. Allen, a local historian points out, “an inspection of this structure gives a clear idea of the general plan followed for all of them.” The Lewis Wall bisects the top of a steep cliff, running on a linear east-west axis for 285 feet. Six feet high at its highest point, with an average thickness of five feet, the structure is a dry-stone rampart containing an estimated forty thousand stones, all of them apparently conveyed by hand up the sheer incline from the dry streambed two hundred feet below. Stone cairns, or ceremonial rock piles, and pits appear at the rear entrance. The structure was raised ingeniously by fitting together mostly flat stones chosen for moderate size and a rough although uniform fit, the same technique used in building the other walls. “They were not insignificant structures,” Allen insists, “and the amount of manual labor required was great. The many thousands of trips necessary to be made from the brook bed to the top of the bluff, often two hundred feet or more above the creek level, represent a stupendous effort for primitive people, the more so when it is considered that some of these walls were six hundred feet long.”

Archaeologists are unable to confidently associate the Lewis Wall with the Indians, who never engaged in large-scale stonework. Nor do any Native American tribes claim it was the labor of their ancestors. Yet the dating of some of the structures has placed it in the middle to late Hopewell time line. Thanks to the availability of organic material embedded in the structure the wall has been radio carbon-dated to 50 AD, the same time period in which the fortifications of the Hopewell culture took place in the Ohio River Valley. Additional dating has taken place more recently and dates of 400 and 900 AD have been confirmed at the Lewis Wall site.

That this monumental partition has stood fundamentally intact for the last twenty centuries in this major earthquake zone is testimony to its skillful construction. In 1812 the region suffered the most powerful earthquake in U.S. history, when the New Madrid Fault generated enough seismic violence to change the course of the Mississippi River and ring church bells in faraway Virginia. The Ohio and the Mississippi rivers flowed north for 3 days according to pioneer journals of the time. Sadly, farmers have pillaged the stones for building materials since the early nineteenth century, rendering a true conception of its original condition difficult to determine. Other examples, like the wall near Stonefort (a town obviously named after the structure), were more than twice as long, stretching more than 650 feet.

Regional author Judy Magee suggests that the structures may have been originally much larger: “These walls, extending east and west from the gateway, were really one wall almost a quarter of a mile in length. Some believed that this wall and the one around Old Stone Fort on the same mountain were originally eight feet high, while, others believed they were as much as ten or even twelve feet high, especially near the gateways and at the ends.”

Writing of this particular wall, investigator Loren Coleman marveled at its formation of an accurate ellipse with axis of 450 and 190 feet. “It is not easy to see how it could have been so accurately laid out,” he writes, “if the area were as heavily forested at the time as it is now.” Clearly, the organized labor and surveying techniques necessary to construct so many massive ramparts belonged to few if any Native American cultures in the area, but certainly typical of the engineering abilities of Roman-era builders.

The line of stone walls all stand on top of finger like high bluffs thrusting southward, from which they are unassailable. Sheer cliffs fall away on either side, but each structure is easily reached from the north over gently sloping ground.

Allen points out that “a man could scale those cliffs only by careful and strenuous effort. They thus have many of the characteristics that would make them into desirable forts.” Their positions appear to have been not only chosen for specific environmental qualities, but also somewhat modified to meet certain military requirements. The erection of this first-century Maginot Line might well have been aimed at keeping away hostile parties. Any attackers would naturally want to strike up the Mississippi and Ohio, but their passing would have been effectively blocked at these easily defended rivers. But what of the stone cairns at the wall entrances? Could they be collapsed towers?

Beyond these wall fragments, the rest of the fortifications must have disintegrated long ago. The abundant forest timber of southern Illinois and scarcity of buildingstone quarries could well have compelled the people of the time to construct their homes, temples, and palaces of wood. Then, as now, builders made their structures from the local material at hand. In the event of a lost war or lethal epidemic, either of which could have forced abandonment of the site and dispersal of the inhabitants, the buildings-reduced to ashes or left to the natural processes of neglect and decay for tens of centuries- – simply would have dissolved without a trace. Of course, if this was the gathering place of a forgotten people they may have only been in the area for a short time. Could this southern tip of Illinois have been a fortified sanctuary in time of trouble, a place of resort to face some invading foe? We will probably never know for sure. But, with the Ohio River on the east flank and the Mississippi on the west flank and the stone walls meandering across the state from the east to the west, forming an inverted pyramid, it would be a great place for a long defensive siege.” Wayne May Ancient American Magazine Volume 50