Next find real artifacts that exist today that are dated during those time frames of 200 BC to 400 AD. Look at their travel patterns and hunter gatherer societies and compare it with the location you have found.

Finally, does the land and these people you are looking for, match these 17 promises and prophecies below as recorded in the Book of Mormon? (I can give you 19 more if you need them). If not, don’t be alarmed. The answer is: “The events of the Book of Mormon happened in the Heartland of the United States of America.” Item 8 below is a {REVELATION}. It shouldn’t be disputed. The way the Meso boys get around this, is they say the entire continent includes the New Jerusalem not just the USA. (So the Promised land could be Greenland, or Nova Scotia, or Venezuela, or Montreal? I guess it could be, but I don’t think it is. The place of the Constitution written by the Lord Himself and the place where the Garden of Eden is located is the Promised Land. What else is an important location of a promised land? Hill Cumorah, Palmyra, Susquehanna, Colesville, Kirtland, Nauvoo, Independence, MO, Salt Lake City? There is overwhelming evidence that as Elder L Tom Perry said, “The United States is the promised land foretold in the Book of Mormon—a palace where divine guidance directed inspired men to create the conditions necessary for the Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ.” Elder L. Tom Perry Ensign Dec. 2012.

Stop looking. The Hopewell Mound builders are the society that match the criteria of what you are looking for.

Historic Hopewell Mounds

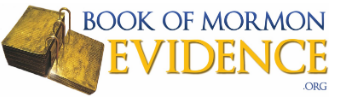

These historic mounds were the ceremonial center of the Hopewell culture from 200 BC – 500 AD. A stretch of land along the North Fork of Paint Creek contains the most striking total set of Hopewell culture remains in Ohio. This enormous legacy of geometric landmarks was created by unknown inhabitants prior to the time of the American Indians living on this land. Their name actually comes from Confederate General Mordecai Hopewell, who owned the land when the mounds were first discovered back in 1840. No one actually knows what name those original builders called themselves.

Interesting similarities, shared by the five mound groups in the Hopewell Culture, make them part of a larger picture. Each field usually has a small circle, a larger circle and a square. Each square is 27 acres and the larger circle would fit perfectly within the square. The large circles all have the same diameter and encompass 20 acres. Many of these appear to have been laid out for their astrological significance.

The main section is often called the “Great Enclosure”, a six foot high, rough, rectangular, earthen enclosure measuring approximately 2800′ X 1800′. Mound 25 is located within this area and was the site of early excavations in the 1800’s. This treasure trove contained shells from the Gulf Coast, copper from Lake Superior region, and obsidian from Wyoming. It appears that when the ceremonial life of a site was finished, they built a mound much like we would put up a headstone or monument”. Source

Why Did the Hopewell People Build Enormous Mounds?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Hopewell_Mica_Claw-56911c573df78cafda8188c8.jpg) Mica Raptor Talon Effigy, Hopewell Culture, Ohio, North America. John Weinstein © The Field Museum

Mica Raptor Talon Effigy, Hopewell Culture, Ohio, North America. John Weinstein © The Field MuseumThe Hopewell culture (or Hopewellian culture) of the United States refers to a prehistoric society of Middle Woodland (c. 100 BC-AD 500) horticulturalists and hunter-gatherers. They were responsible for building some of the largest indigenous earthworks in the country, and for obtaining imported, long distance source materials from Yellowstone Park to the Gulf coast of Florida.

Geographically, Hopewell residential and ceremonial sites are located in the American eastern woodlands, concentrated along the river valleys within the Mississippi watershed including parts of the Missouri, Illinois and Ohio Rivers. Hopewell sites are most common in Ohio (called the Scioto tradition), Illinois (Havana tradition) and Indiana (Adena), but they can also be found in parts of Wisconsin, Michigan, Iowa, Missouri, Kentucky, West Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, Louisiana, North and South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and Florida. The largest cluster of earthworks are found in the Scioto River Valley of southeastern Ohio, an area which is considered by scholars the Hopewell “core”.

Settlement Patterns

The Hopewell built some truly spectacular ritual mound complexes out of sod blocks–the best known is the Newark mound group in Ohio. Some Hopewell mounds were conical, some were geometric or effigies of animals or birds. Some of the groups were enclosed by rectangular or circular sod walls; some may have had a cosmological significance.

Generally, the earthworks were solely ritual architecture, where nobody lived full time but ritual activity included the manufacture of exotic goods for burials, as well as feasting and burial ceremonies. The people are thought to have lived in small local communities of between 2-4 families, dispersed along the fringes of rivers and connected to one or more mound centers by shared material cultural and ritual practices.

Rockshelters, if available, were often used as hunting campsites, where meat and seeds may have been processed before returning to base camps.

Hopewell Economy

At one time, archaeologists thought that anyone who built such mounds must have been farmers: but archaeological exploration has clearly identified the builders of the mounds as horticulturalists, who built earthworks, participated in long-distance exchange networks, and only periodically traveled to earthworks for social/ceremonial gatherings.

Much of the diet of the Hopewell people was based on hunting white-tailed deer and freshwater fish, nuts and seeds, supplemented by the tending and shifting slash and burn methods of growing local seed-bearing plants such as maygrass, knotweed, sunflowers, chenopodium and tobacco.

This defines the Hopewell semi-sedentary horticulturalists, who exercised a varying degree of seasonal mobility, following the various plants and animals as the weather changed throughout the year.

Artifacts and Exchange Networks

It is really unknown how much of the exotic materials found in the mounds and residential areas got there as a result of long-distance trade or as a result of seasonal migrations or long distance travels. But, quite nonlocal artifacts are found in many Hopewell sites, and were manufactured into a variety of ritual objects and tools.

- Appalachian mountains: black bear teeth, mica, steatite

- Upper Mississippi valley: galena and pipestone

- Yellowstone: obsidian and bighorn sheep horns

- Great Lakes: copper and silver

- Missouri River: Knife River Flint

- Gulf and Atlantic coast: marine shell and shark’s teeth

Craft specialists made pottery, lithic tools, and textiles, in addition to exotic ritual artifacts.

Status and Class

It seems inescapable: there is evidence for the presence of an elite class, in the form of non-utilitarian grave goods from imported and local materials, complex burial mounds, and elaborate mortuary processing facilities, all used for a segment of the society. Selected deceased individuals were processed in ritual center charnel houses and then buried in mounds with exotic funerary offerings.

What additional control those individuals had while living, apart from earthbound construction, is difficult to establish. It may have been kin-based councils or non-kin sodalities; it may have been some hereditary elite group who arranged for the feasting and earthwork construction and maintenance.

Archaeologists have used stylistic variations and geographic localities to identify tentative peer polities, small collections of groups that were centered around in one or more mound centers, particularly in Ohio. Relations between the groups were typically nonviolent among different polities based on the relative lack of traumatic injuries on Hopewell skeletons.

The Rise and Fall of the Hopewell

The reason why hunter-gatherer/horticulturalists built big earthworks is a puzzle–but one shared by the earlier American Archaic tradition. It is possible that the florescence of mound construction occurred because of the uncertainty of the small communities, created by greater sedentism, territoriality, population aggregation along the waterways. If so, then economic relationships might have been established and maintained through public ritual, or mark territory or corporate identity. Some evidence exists suggesting at least some of the leaders were shamans, religious leaders.

Little is known about why Hopewell mound-building ended, either about AD 200 in the lower Illinois Valley and about AD 350-400 in the Scioto river valley. There is no evidence of failure, no evidence of widespread diseases or heightened death rates: basically, the smaller Hopewell sites simply aggregated into larger communities, located away from the Hopewell heartland, and the valleys were largely abandoned.

Hopewell Archaeology

Hopewell archaeology began in the early 20th century with the discovery of spectacular artifacts of stone, shell, and copper from mounds in a complex on Mordecai Hopewell’s farm on a tributary stream of the Scioto River in southcentral Ohio.

A few more sites:

- Ohio: Mound City, Tremper mounds, Fort Ancient, Newark Earthworks, Hopewell site

- Illinois: Pete Klunk, Ogden Fettie,

- Georgia: Kolomoki

Sources

https://www.thoughtco.com/hopewell-culture-north-americas-mound-building-170013brams EM. 2009. Hopewell Archaeology: A View from the Northern Woodlands. Journal of Archaeological Research 17(2):169–204.

Bolnick DA, and Smith DG. 2007. Migration and social structure among the Hopewell: Evidence from ancient DNA. American Antiquity 72(4):627-644.

DeBoer WR. 2004. Little Bighorn on the Scioto: The Rocky Mountain Connection to Ohio Hopewell. American Antiquity 69(1):85-108.

Giles B. 2013. A Contextual and Iconographic Reassessment of the Headdress on Burial 11 From Hopewell Mound 25. American Antiquity 78(3):502-519.

Magnani M, and Schroder W. 2015. New approaches to modeling the volume of earthen archaeological features: A case-study from the Hopewell culture mounds. Journal of Archaeological Science 64:12-21.

McConaughy MA. 2005. Middle Woodland Hopewellian Cache Blades: Blanks or Finished Tools? Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 30(2):217-257.

Miller GL. 2015. Ritual economy and craft production in small-scale societies: Evidence from microwear analysis of Hopewell bladelets. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology39:124-138.

Van Nest J, Charles DK, Buikstra JE, and Asch DL. 2001. Sod blocks in Illinois Hopewell mounds. American Antiquity 66(4):633-650.

Wright AP, and Loveland E. 2015. Ritualised craft production at the Hopewell periphery: new evidence from the Appalachian Summit. Antiquity 89(343):137-153.

Yerkes RW. 2005. Bone chemistry, body parts, and growth marks: Evaluating Ohio Hopewell and Cahokia Mississippian seasonality, subsistence, ritual, and feasting.American Antiquity 70(1):241-266.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Hopewell_Culture_National_Historic_Park-8cb6d5088aba48a4992b076ec9d7e9e8.jpg)