Lehi’s First Landing

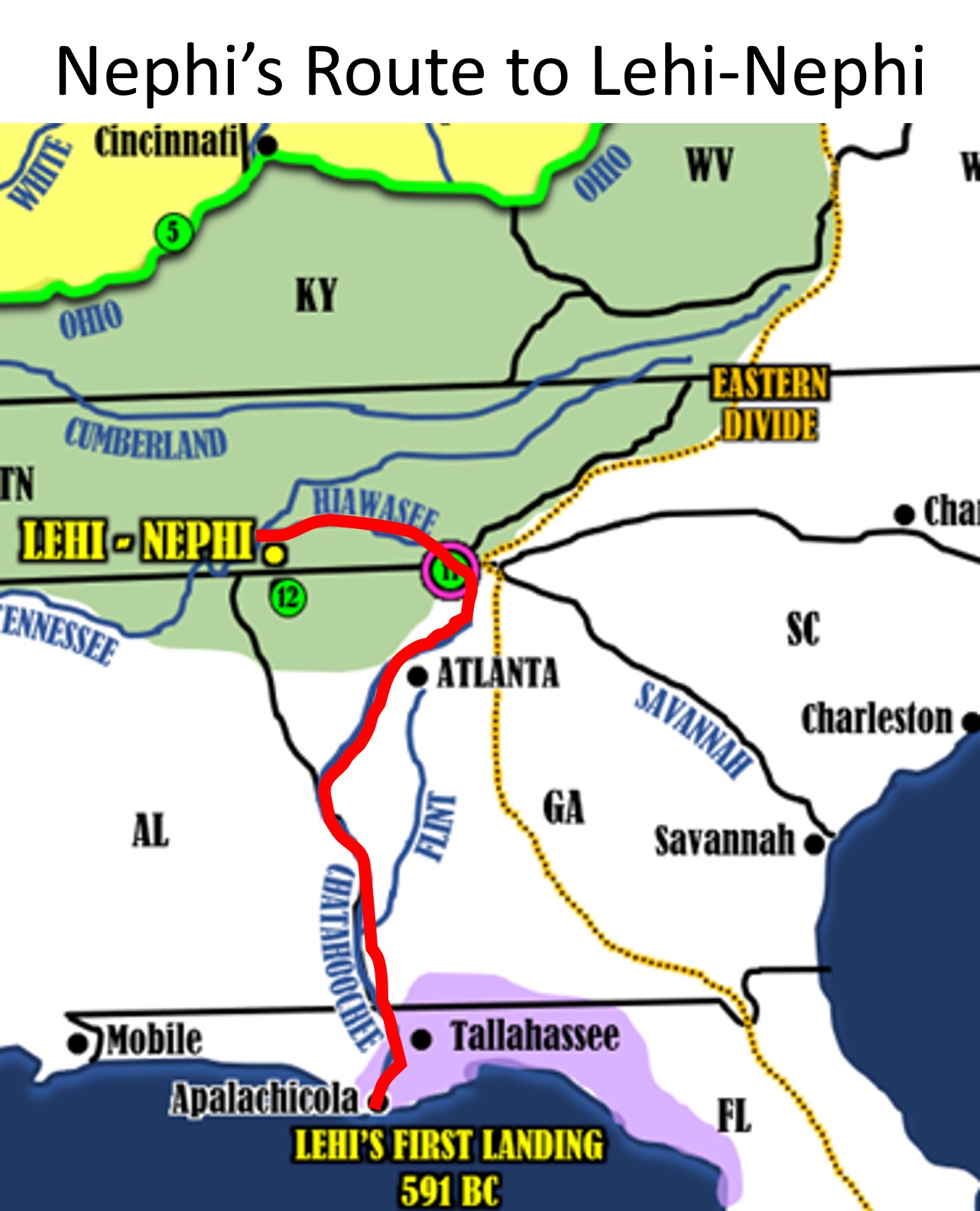

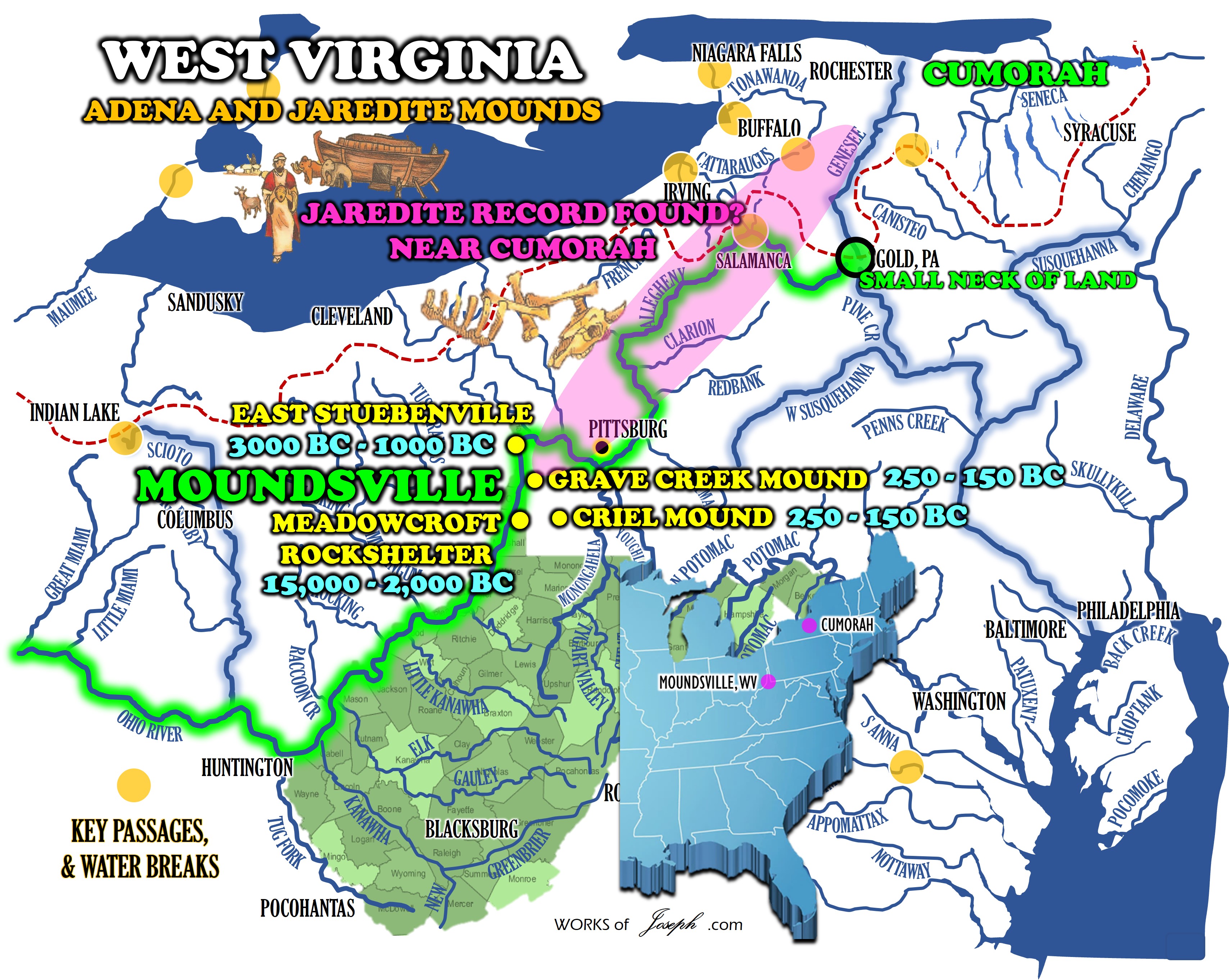

I am proposing a possible location of the Jaredite record which was found by the people of Limhi. [200 B.C. MOSIAH 8:8-9] We believe near Tallahassee FL is where Lehi Landed. Nephi escaped up the Chattahoochee River to Tennessee. We also have an understanding that the City Lehi-Nephi was at Chattanooga, TN. From there in about 329 BC Mosiah left and went down the Tennessee’s River which connects with the Ohio and Mississippi which west directly north to Zarahemla. Read Blog here:

Nephi’s Route

“And after we had journeyed for the space of many days we did pitch our tents.” 2 Nephi 5:7 (Apalachicola, FL to Unicoi Gap, GA is about 400 miles or 8-10 days journey for a Nephite on the river). To escape his brothers, Nephi traveled up the Chattahoochee River to its head at Unicoi Gap, GA. Just 1,700 feet from that head, is also the head of the Hiawasee River which flows north west right to the Tennessee River and on to Chattanooga, TN.

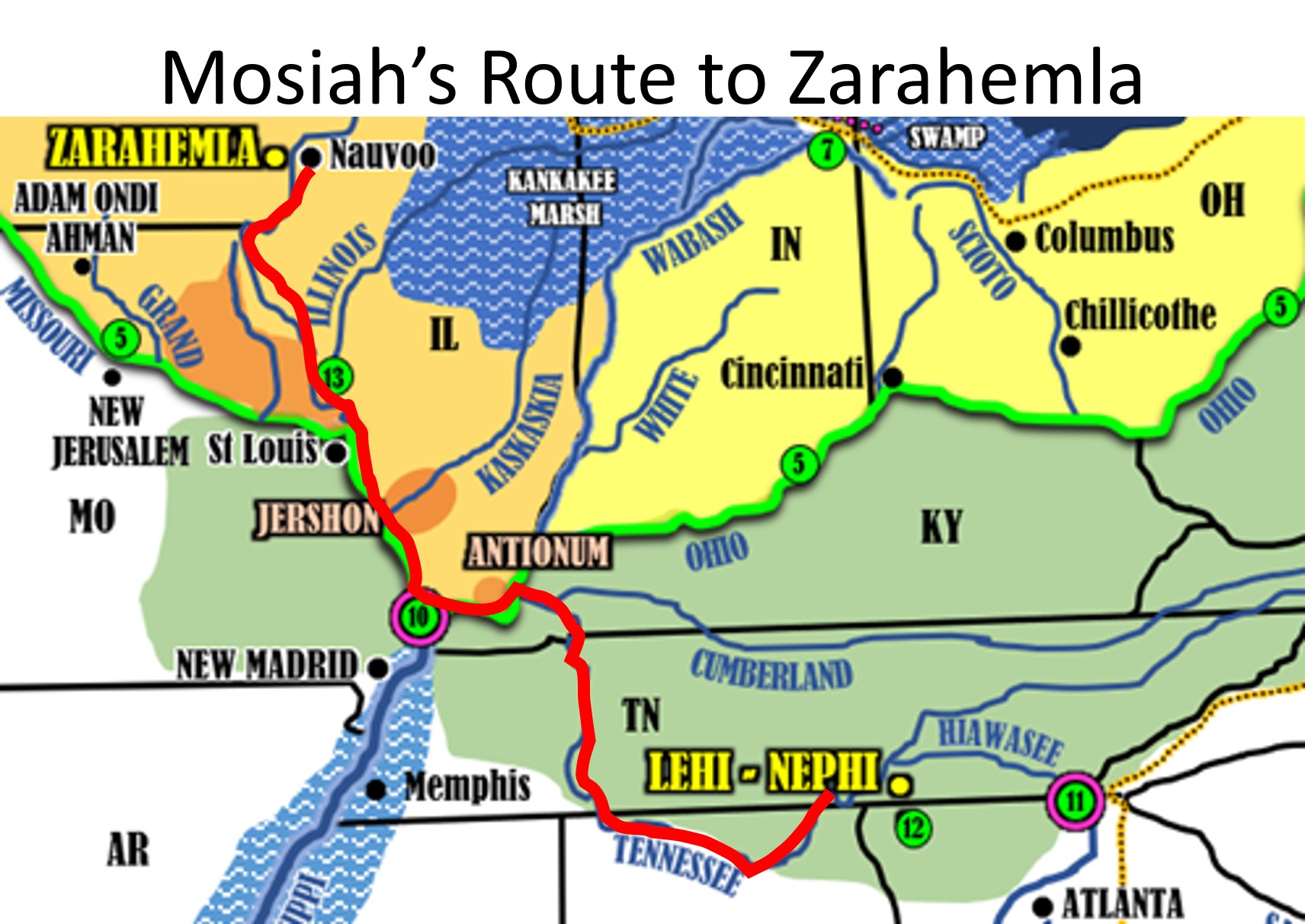

Mosiah’s Route

Mosiah’s Route

From Chattanooga, TN Mosiah would travel downstream the Tennessee River which heads east and then takes a sharp curve north, then to the Ohio River and then take the Ohio west to the Head of River Sidon, (Confluence of Ohio and Mississippi rivers), then travel north upstream on the Mississippi to Zarahemla.

The Land of Zarahemla is a lower elevation than the Land Nephi. “Nephites and Lamanites are always traveling up from the land of Zarahemla to the land of Nephi, and down from the land of Nephi to the land of Zarahemla… When you read the text, think of the geography from Alma 22; i.e., the Sidon is the upper Mississippi River, and it flows south. To go from the land of Zarahemla to the land of Nephi, you travel east up the Ohio River and then south upstream on the Tennessee River.” Moroni’s America page 45

Limhi’s Lost Route Trying to Find Zarahemla

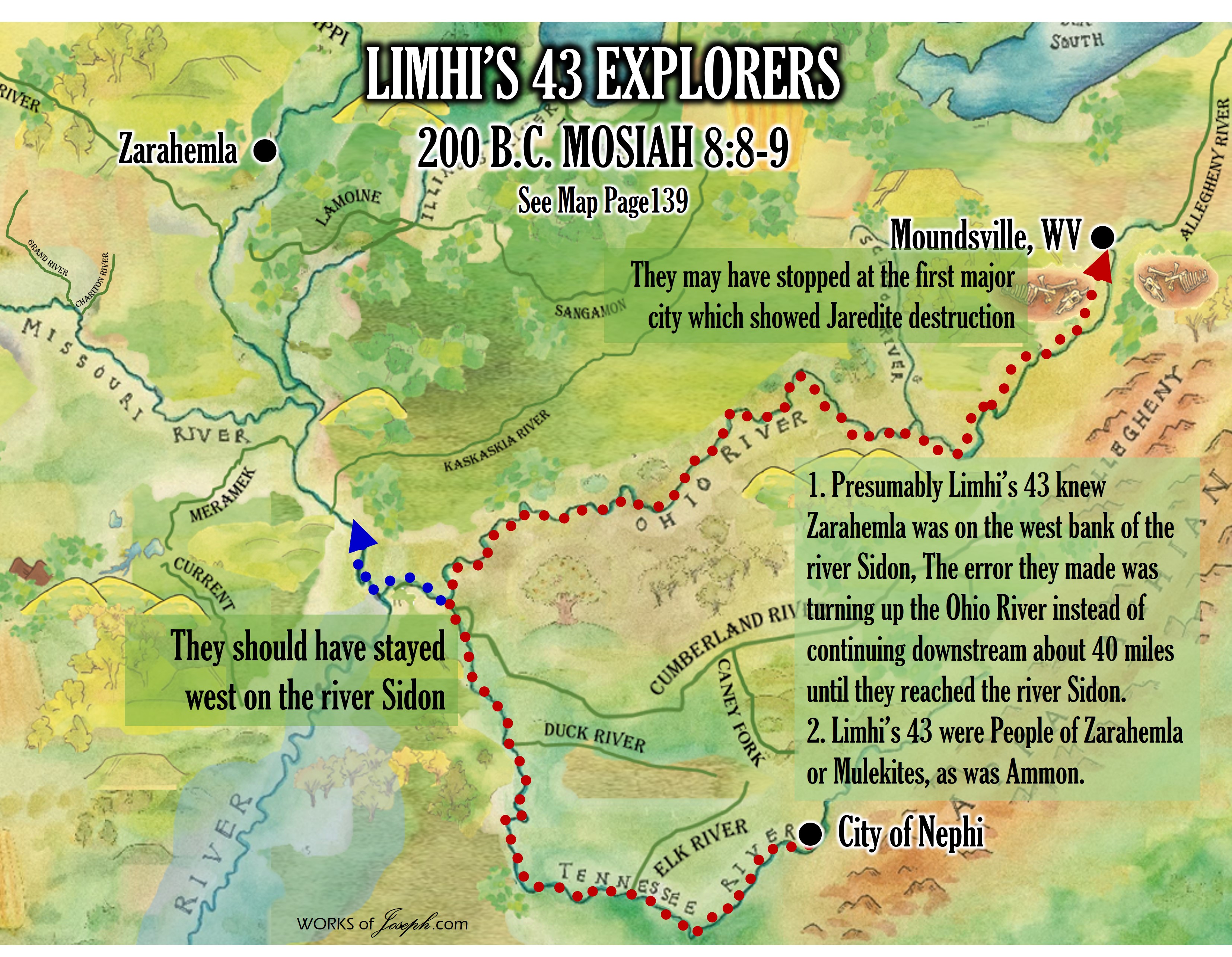

Did they end up in West Virginia? I believe, yes! Presumably, Limhi’s 43 knew Zarahemla was on the west bank of the river Sidon. From Chattanooga to Zarahemla would require traveling up-river or north on the Tennessee River. When the Tennessee meets the Ohio River, Limhi probably went upstream on the Ohio, instead of downstream on the Ohio where it meets the Mississippi River at the Head of River Sidon. The error they made was turning west instead of continuing about 40 miles until they reached the river Sidon [Mississippi], and then continue north to Zarahemla. See Map above.

Presumably, Limhi’s 43 knew Zarahemla was on the west bank of the river Sidon. From Chattanooga to Zarahemla would require traveling up-river or north on the Tennessee River. When the Tennessee meets the Ohio River, Limhi probably went upstream on the Ohio, instead of downstream on the Ohio where it meets the Mississippi River at the Head of River Sidon. The error they made was turning west instead of continuing about 40 miles until they reached the river Sidon [Mississippi], and then continue north to Zarahemla. See Map above.

By traveling up stream on the Ohio, they may have stopped at the first major city which showed Jaredite destruction on the Ohio/Allegheny River between about Moundsville WV to possibly even Pittsburg, PA where the Allegheny and Ohio confluence is. We are confident that the battles of the Jaredites probably went all along the Ohio River from West Virginia through Pennsylvania to New York where it ended at hill Ramah (Same hill the Nephites called Cumorah). See Ether 15:11

It is interesting to know that Limhi’s 43 were People of Zarahemla or Mulekites, as was Ammon. This is why they wanted to find their blood brothers back in Zarahemla.

Ammon a Mulekite (Hebrew)

“And it came to pass that on the morrow they started to go up, having with them one Ammon, he being a strong and mighty man, and a descendant of Zarahemla; and he was also their leader.” Mosiah 7:3

Limhi a Mulekite (Hebrew)

“And he said unto them: Behold, I am Limhi, the son of Noah, who was the son of Zeniff, who came up out of the land of Zarahemla to inherit this land, which was the land of their fathers, who was made a king by the voice of the people.” Mosiah 7:9

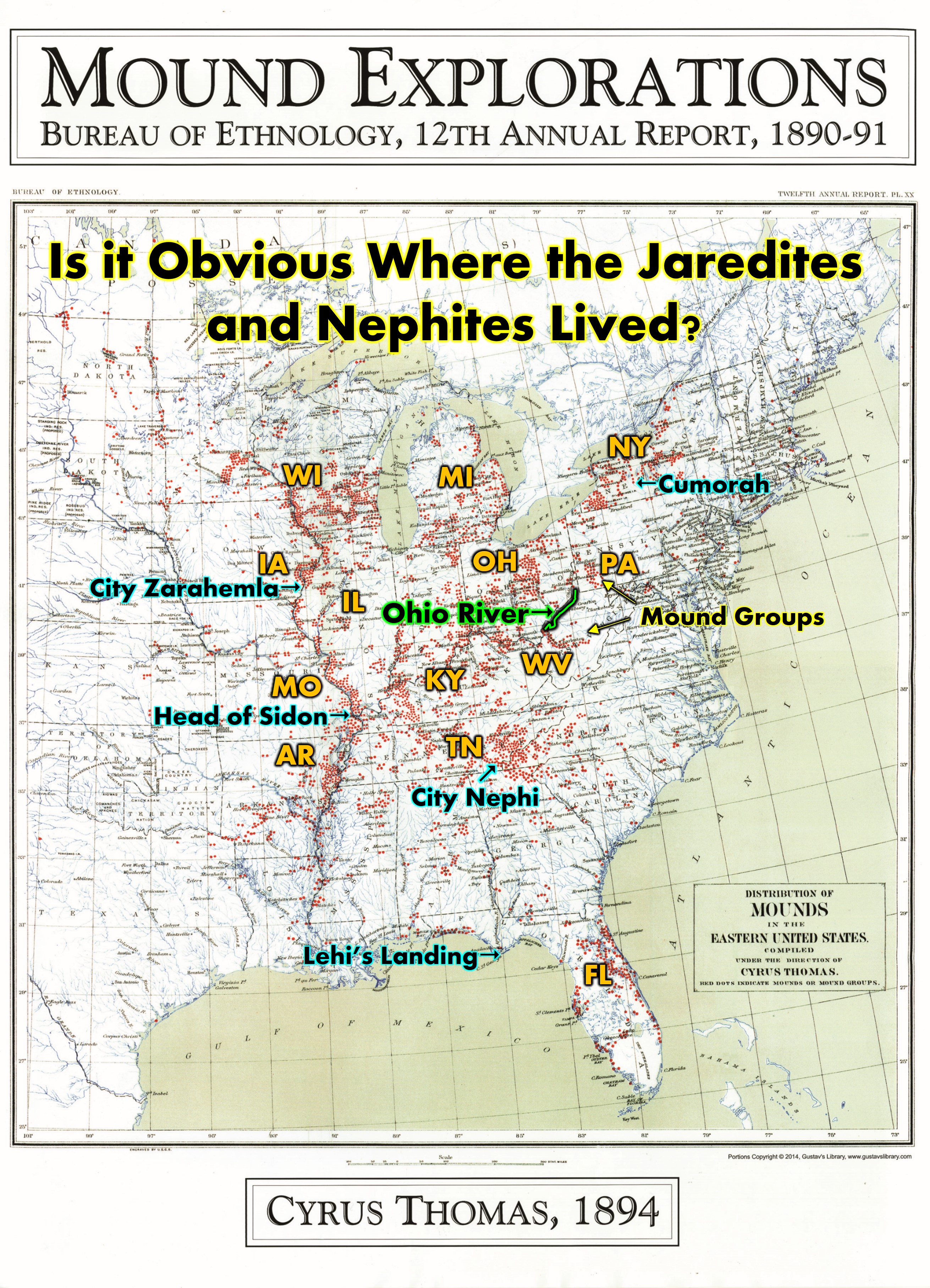

MOSIAH 8:7 LIMHI’S 43 LOST EXPLORERS FOUND JAREDITE RECORD IN WV? Review the map above to better help in understanding.

Known Mounds Today in West Virginia

Meadowcroft Rockshelter may be the oldest known site of human habitation in North America, The artifacts uncovered in these areas give evidence of a village society with a tribal trade system culture that included limited cold worked copper. As of 2009, over 12,500 archaeological sites have been documented in West Virginia.” Extract from ”Catalogue of prehistoric works east of the Rocky Mountains by Cyrus Thomas 1891

Large Yellow Dots on Map shows Important geological areas of Jaredite and Nephite lands. Rivers, Gaps, Confluences, Ridges, Divides, etc.

Now let’s look at two specific mounds that remain today in West Virginia that were, according to scientists, built from about 250-150 BC. This was the exact time of Limhi’s travels.

Follow my blog daily at bookofmormonevidence.org/blog

The Criel Mound

Wikipedia continues, “The Criel Mound is part of the second-largest known concentration of Adena mounds and circular enclosures which Cyrus Thomas called the “Kanawha Valley Mounds”. This area extends for eight miles (13 km) along the upper terraces of the Kanawha River floodplain, in the vicinity of present-day Charleston. In 1894, Cyrus Thomas reported 50 mounds in this area, ranging from 3’ to 35’ in height and from 35’ to 200’ in diameter. He also reported finding eight to ten circular earthworks, enclosing from 1 to 30 acres (120,000 m2). Stone mounds dotted the bluffs above the floodplain.

While many of the original Adena mounds were destroyed during later development of the area, a few remain. The Wilson Mound is in a private cemetery in South Charleston. A recreation of the original Shawnee Reservation Mound exists in Institute, West Virginia.” Wikepedia

The Grave Creek Mound

(See the art as the featured image above) “The Grave Creek Mound in the Ohio River Valley in West Virginia is one of the largest conical-type burial mounds in the United States, now standing 62 feet (19 m) high and 240 feet (73 m) in diameter. The builders of the site, members of the Adena culture, moved more than 60,000 tons of dirt to create it about 250–150 BC.

Present-day Moundsville has developed around it near the banks of the Ohio River. The first recorded excavation of the mound took place in 1838, and was conducted by local amateurs Abelard Tomlinson and Thomas Biggs. The largest surviving mound among those built by the Adena, this was designated a National Historic Landmark in the mid-20th century.

Grave Creek Mound is the largest conical type of any of the mound builder structures. Construction of the earthwork mound took place in successive stages from about 250–150 B.C., as indicated by the multiple burials at different levels within the structures. In 1838, road engineers measured its height at 69 feet (21 m) and its base as 292 feet (89 m).” Wikipedia

West Virginia Archives and History

Mounds & Mound Builders

The Adena people were the first Native Americans to build ceremonial mounds. In other parts of the world, ceremonial burials had occurred much earlier. The Egyptian pyramids date to 2700 BCE; in England, stone chambers called barrows were used as early as 2000 BCE; between 1700 and 1400 BCE, keirgans were used in central Siberia; and the burial mounds of the Choo Dynasty in northern China date to 1000 BCE.

We know little about how or why the mounds were built. Historian Otis Rice suggests these early Americans “built mounds over the remains of chiefs, shamans, priests, and other honored dead.” For their “common folk,” the Adenas cremated the dead bodies, placing the remains in small log tombs on the surface of the ground. Virtually all of these graves have been destroyed by nature and later settlement. Therefore, the more substantial mounds are our only physical records of Adena burials.

The Grave Creek Mound in Moundsville (Marshall County) is the largest conical type burial mound in the United States, approached in size by only the Miamisburg, Ohio mound.  The mound, 62 feet high and 240 feet in diameter, contains approximately 57,000 tons of dirt and originally stood nearly 70 feet high. The digging of so much earth left a sizeable moat or ditch surrounding the mound, no longer in existence. By testing the soil, archaeologists estimate the mound was built between 250 and 150 BCE by the Adena culture, which occupied the area from about 1000 BCE to 200 CE. The mound and two forts were the essential features of an Adena village in the shape of a triangle. “The mound construction probably began with the death of a very important person. There is no way to know who this person was — great warrior, chieftain or religious leader. We know that 25-30 years later another important personage died and his remains were placed in an 8 by 12 foot vault on the top of the mound when it was approximately 35 feet high. The natives then covered this with dirt until the mound reached its maximum height.”1

The mound, 62 feet high and 240 feet in diameter, contains approximately 57,000 tons of dirt and originally stood nearly 70 feet high. The digging of so much earth left a sizeable moat or ditch surrounding the mound, no longer in existence. By testing the soil, archaeologists estimate the mound was built between 250 and 150 BCE by the Adena culture, which occupied the area from about 1000 BCE to 200 CE. The mound and two forts were the essential features of an Adena village in the shape of a triangle. “The mound construction probably began with the death of a very important person. There is no way to know who this person was — great warrior, chieftain or religious leader. We know that 25-30 years later another important personage died and his remains were placed in an 8 by 12 foot vault on the top of the mound when it was approximately 35 feet high. The natives then covered this with dirt until the mound reached its maximum height.”1

The first person of European descent to discover the mound was early settler Joseph Tomlinson, who literally stumbled off the top while hunting in 1770. In 1838, descendants Jesse and Abelard Tomlinson, and Thomas Briggs gutted the mound, destroying much of the archaeological evidence provided by the scientific study of other mounds. Tunneling from the side and top, the two men discovered a burial chamber in the center containing two skeletons and large amount of jewelry and another room with one skeleton and jewelry. Tomlinson opened the center chamber as a museum, charging 25 cents admission. Five years later, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft mapped the area. In 1909, the state acquired possession of the mound, placing it under the care of West Virginia Penitentiary warden M. S. White. In 1975, Dr. E. Thomas Hemmings of the West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey conducted the first scientific excavation of the area, locating among other items the previous existence of a moat. During the last two hundred years, the top of the mound has been home to a saloon, dance platform, and artillery pieces during the Civil War. Today, the state operates the Grave Creek Mound State Park and Delf Norona Museum and Culture Center, featuring numerous Native American artifacts from the mound and region.2

The Criel Mound in South Charleston is the largest of approximately fifty conical type mounds of the Adena culture in an area west of Charleston extending to Institute.  The precise age of the Criel Mound is unknown, but archaeologists believe it dates to the time of the Grave Creek Mound in Moundsville, probably built between 250 and 150 BCE. It was the burial ground for an Indian village located on the site of the city of South Charleston some 2,000 years ago. It is unknown when the village disappeared, although some have suggested it remained until as late as 1650 CE In West Virginia, the 35-foot high and 175-foot diameter Criel Mound is exceeded in size only by the Grave Creek Mound.3

The precise age of the Criel Mound is unknown, but archaeologists believe it dates to the time of the Grave Creek Mound in Moundsville, probably built between 250 and 150 BCE. It was the burial ground for an Indian village located on the site of the city of South Charleston some 2,000 years ago. It is unknown when the village disappeared, although some have suggested it remained until as late as 1650 CE In West Virginia, the 35-foot high and 175-foot diameter Criel Mound is exceeded in size only by the Grave Creek Mound.3

The Criel Mound was first excavated by Professor P. W. Norris of the Smithsonian Institute in 1883 and 1884. Tunneling from the top down, the archaeologists discovered the following:

At the depth of 3 feet, in the center of the shaft, some human bones were discovered, doubtless parts of a skeleton said to have been dug up before or at the time of the construction of the judges’ stand. At the depth of 4 feet, in a bed of hard earth composed of mixed clay and ashes, were two skeletons, both lying extended on their backs, heads south, and feet near the center of the shaft. Near the heads lay two celts, two stone hoes, one lance head, and two disks.4

As they dug to a depth of 31 feet, numerous other skeletons were found, including a burial vault containing the remains of eleven Native Americans thought to have been killed in battle. There was also evidence that some may have been buried alive. As was the custom, various jewelry and weapons were placed in the buried vaults. Today, all the artifacts and skeleton remains are maintained at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C. 5″ West Virginia Archives and History

Notes

1. History of Marshall County West Virginia 1984 (Marshall County Historical Society, 1984), 6.

2. History of Marshall County West Virginia 1984, 6-7; Phil Conley and William Thomas Doherty, West Virginia History (Charleston: Education Foundation, Inc., 1974), 51-52.

3. Stephen B. Preston, “An Introduction to the Mound Builders and the Criel Mound, `D’ Street, South Charleston,” in J. Alfred Poe and Albert Giles, “The History of South Charleston, West Virginia, Volume I,” (hereafter Preston, “Mound Builders”), 16, 18.

4. “Ancient Works Near Charleston,” U. S. Bureau of Ethnology, Twelfth Annual Report, 1890-91 (Washington, D.C.), as quoted in Preston, “Mound Builders,” 14.

5. Phil Conley and William Thomas Doherty, West Virginia History (Charleston: Education Foundation, Inc., 1974), 52-53; Otis K. Rice, West Virginia: A History (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1985), 5-6.

Truth is amazing. It is so important to ask questions and research. Truth is everywhere. Today our governments, politicians, corporate heads, Big Pharma, Big Tech, social media and main street media, continue to lie to us to maintain power and create a slave state. Even this amazing geography information has been kept from us. Thanks to Rod Meldrum, Wayne May, and Dean Sessions for being brave enough to share truth at the expense of all the evil that try’s and keep us bound. And thank to all those who read this and share it with family and friends.