Lamanite, A North American Indian

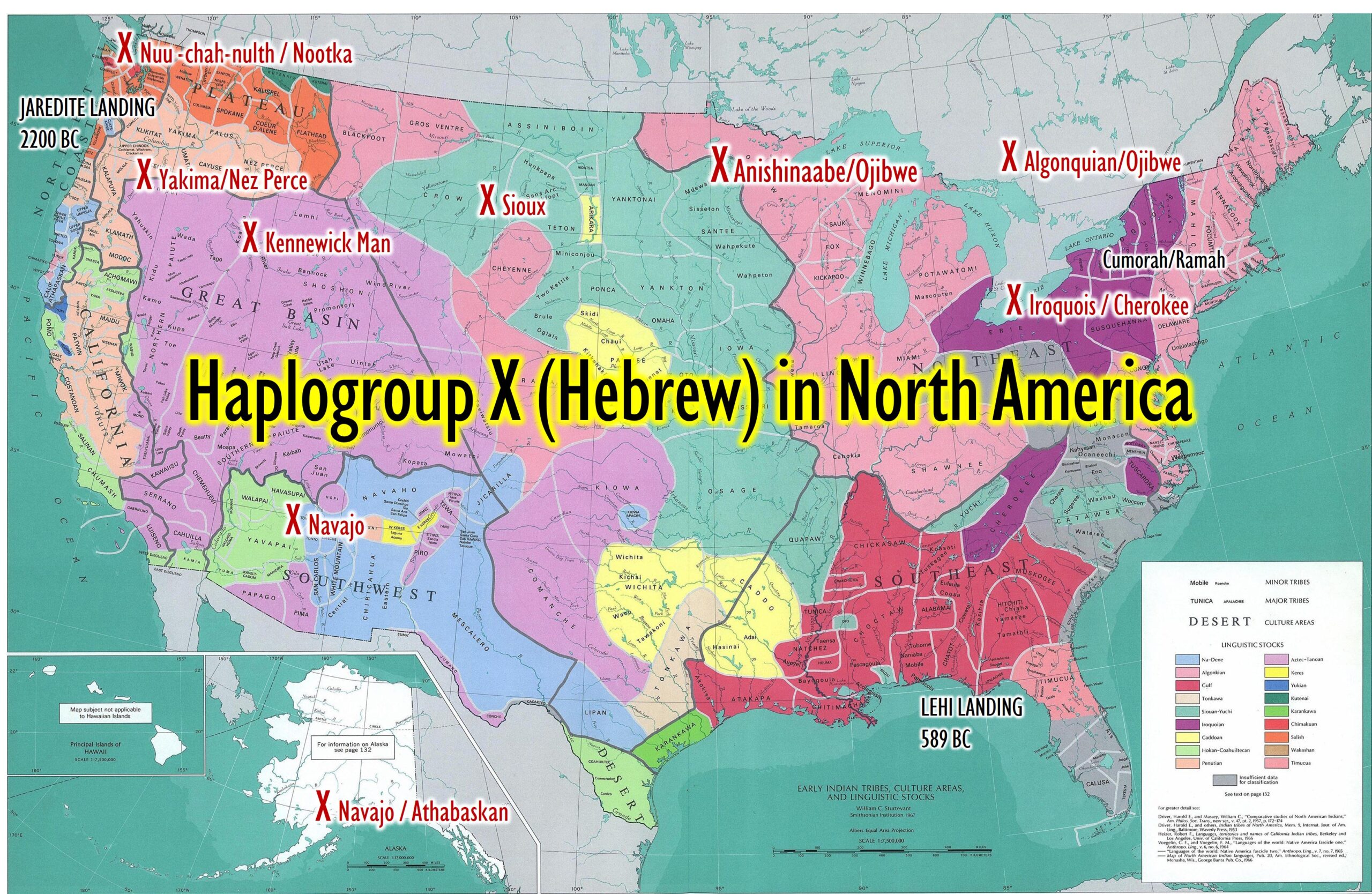

“I think it’s important to realize that the title page of the Book of Mormon says, “written to the Lamanites. That’s one of the very first things it says. I think Latter-day Saints today think well, the Book of Mormon is written for us. Well it was, written for the entire world, but of course Mormon, Moroni in their understanding of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon, they fully realized that this book, this record, would eventually come forth to their descendants to the descendants of Lehi, and his family. And, this is clear to Joseph Smith. There’s no question in my mind that Joseph Smith knows from the very beginning this record needs to be received and given to and accepted by Lamanite descendants. And in 1830, to Joseph Smith and the Church members, a Lamanite meant to them, a North American Indian. There’s just no question.” Alexander L. Baugh BYU Church History Department; transcribed from the documentary “History of the Saints” Mission to the Lamanites Part 1.

The White Man

“As yet I know of no species that was exterminated until the coming of the white man … The white man considered animal life just as he did the natural man life upon this continent as “pests.” There is no word in the Lakota vocabulary with the English meaning of this word … Forests were mown down, the buffalo exterminated, the beaver driven to extinction and his wonderfully constructed dams dynamited … and the very birds of the air silenced … The white man has come to be the symbol of extinction for all things natural in this continent. Between him and the animal there is no rapport and they have learned to flee from his approach, for they cannot live on the same ground.” Chief Luther Standing Bear, Land of the Spotted Eagle, Houghton Mifflin, Boston & New York, 1933.

I truly believe the Spirit of Christ was given to all men and women as we each chose to live on this earth. Our challenge is, who will live up to that “Great Spirit’s desires which He has for each of us, and who will not?

We are all equal in God’s eyes, both male and female, bond and free, black and white, and I believe the Lord’s greatest desire is to see all of His children live together in love and peace. It’s unfortunate how the White Man has treated the Native American and their descendants the Hebrews. As you read below, you will come to realize the true Spirit contained within these special Lamanites of North America and all other nationalities on this beautiful Earth. I share the quote below as a tribute to Mike and Betty LaFontaine who truly know they are people from the East.

Thankful to the East

“We are thankful to the East because everyone feels good in the morning when they awake, and sees the bright light coming from the East; and when the Sun goes down in the West we feel good and glad we are well; then we are thankful to the West. And we are thankful to the North, because when the cold winds come we are glad to have lived to see the leaves fall again; and to the South, for when the south wind blows and everything is coming up in the spring, we are glad to live to see the grass growing and everything green again. We thank the Thunders, for they are the Manitou’s that bring the rain, which the Creator has given them power to rule over. And we thank our mother, the Earth, whom we claim as mother because the Earth carries us and everything we need.” Charley Elkhair, quoted in M. R. Harrington, Religion and Ceremonies of the Lenape, Indian Notes and Monographs, Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, vol 19 (1921).

1830

“The Book of Mormon was published the same year the Indian Removal Act passed. It gave Church members a different perspective on the past history and future destiny of American Indians. The early Saints believed that all American Indians were the descendants of Book of Mormon peoples, and that they shared a covenant heritage connecting them to ancient Israel. They often held the same prejudices toward Indians shared by other European Americans, but Latter-day Saints believed Native Americans were heirs to God’s promises even though they now suffered for once having rejected the gospel. This belief instilled in the early Saints a deeply felt obligation to bring the message of the Book of Mormon to American Indians.

Within months of the founding of the Church in 1830, Latter-day Saint missionaries journeyed to Indian Territory, on the borders of the United States. Parley P. Pratt reported that William Anderson (Kik-Tha-We-Nund), the leader of a group of Delaware (Lenape) who had relocated to the area near Independence, Missouri, warmly received the missionaries, and an interpreter told Oliver Cowdery that the “chief says he believes every word” of the Book of Mormon. However, a government agent soon barred them from further evangelizing among Indians in the area because they had not secured proper authorization. Latter-day Saint interactions with American Indians remained sparse for the next few years, though Pratt and others still spoke of a day when Indians would embrace the Book of Mormon.” Church History Topics

Lamanite Tradition

“We can learn much from the Native Americans. At one time they each had the true gospel with the priesthood in their homes. We know through transgression they lost those blessings, but retain many of the oral traditions of the gospel.

We have heard it said “the first shall be last and the last shall be first”. What can we learn from the Native Americans? I have always known the Native American believe in only one God. They worship the Great Spirit. They are a humble and proud people with a wonderful sense of humor. They only allow their High Priest to speak the sacred things of God.

“It is interesting to note, in closing, that I know of no Indian language in which one can take the name of the Lord in vain. Indeed, I do not know of an Indian language in which they can even swear. They have to learn English or some white man’s language before they can defile the name of Deity.” LAMANITE TRADITION by Golden R. Buchanan PRESIDENT, SOUTHWEST INDIAN MISSION IMPROVEMENT ERA APRIL 1955 SPECIAL LAMANITE ISSUE

Turtle Island

For some Indigenous peoples, Turtle Island refers to the continent of North America. The name comes from various Indigenous oral histories that tell stories of a turtle that holds the world on its back. For some Indigenous peoples, the turtle is therefore considered an icon of life, and the story of Turtle Island consequently speaks to various spiritual and cultural beliefs.

Origin and Definition

Origin and Definition

Turtle Island is the name many Algonquian- and Iroquoian-speaking peoples mainly in the northeastern part of North America use to refer to the continent. In various Indigenous origin stories, the turtle is said to support the world, and is an icon of life itself. Turtle Island therefore speaks to various spiritual beliefs about creation and for some, the turtle is a marker of identity, culture, autonomy and a deeply-held respect for the environment.

Story of Turtle Island

The story of Turtle Island varies among Indigenous communities, but by most accounts, it acts as a creation story that places emphasis on the turtle as a symbol of life and earth. The following versions are brief reinterpretations of stories shared by Indigenous peoples. In no way do these examples represent all variations of the tale; they merely seek to demonstrate general characteristics and plots of different stories. Source

North American Indians: the Spirituality of Nature

Every seed is awakened and so is all animal life. It is through this mysterious power that we too have our being and we therefore yield to our animal neighbours the same right as ourselves, to inhabit this land. Sitting Bull

The environmental wisdom and spirituality of North American Indians is legendary.

Animals were respected as equal in rights to humans. Of course they were hunted, but only for food, and the hunter first asked permission of the animal’s spirit. Among the hunter-gatherers the land was owned in common: there was no concept of private property in land, and the idea that it could be bought and sold was repugnant. Many Indians had an appreciation of nature’s beauty as intense as any Romantic poet.

Religious beliefs varied between tribes, but there was a widespread belief in a Great Spirit who created the earth, and who pervaded everything. This was a panentheist rather than a pantheist belief. But the pantheistic tone was far stronger than among Christians, and more akin to the pantheism of William Wordsworth. It was linked to an animism which saw kindred spirits in all animals and plants.

The Indians viewed the white man’s attitude to nature as the polar opposite of the Indian. The white man seemed hell-bent on destroying not just the Indians, but the whole natural order, felling forests, clearing land, killing animals for sport.

Of course, not everything that every Indian tribe did was wonderfully earth-wise and conservation-minded. The Anasazi of Chaco Canyon probably helped to ruin their environment and destroy their own civilization through deforestation. In the potlatch the Kwakiutl regularly burned heaps of canoes, blankets and other possessions simply to prove their superiority to each other; the potlatch is the archetypal example of wanton overconsumption for status. Even the noble plains Indians often killed far more bisons than they needed, in drives of up to 900 animals.

In other words, the Indians were not an alien race of impossibly wonderful people. They were human just like the rest of us. And in that lies hope.

Wisdom derives from way of life, and is as fragile as nature. Many Indians shared their animism, their respect for nature and their attitude to the land with other hunter-gatherers. But when ways of life change, beliefs change to support them. The advent of agriculture and then industry brought massive shifts in attitudes to nature (see How we fell from unity.)

Beliefs can also change ways of life. Our present way of life is laying waste to the environment that supports us. New beliefs can help us to change that way of life, and in arriving at those beliefs, we can learn immensely from the beliefs of the North American Indians. Source North American Indians: the spirituality of nature

Our Brothers and Sisters: 5 Sacred Animals and What They Mean in Native Cultures

Indian Country Today Vincent Schilling 2014

Indigenous cultures carry precious knowledge about the world around us, including human relationship with animals.

Without a doubt, animals are a huge part of Native culture. They are considered our brothers and sisters, among our winged, four-legged and swimming family members. They are part of our creation stories, they are messengers to the ancestors and the Creator, and they are our teachers on this world.

In an attempt to give a bit of respect to our sacred animals, we have compiled a bit of cultural information about our brother and sister brethren. Here are six sacred animals and what they mean.

The Eagle

Because the eagle is the animal that flies the highest in the animal kingdom, many tribes have believed they are the most sacred, the deliverers of prayers to the Creator. Additionally, the eagle feather as a gift is considered the highest honor to be given.

The eagle is an animal of leadership, and in most cultures it is considered a dishonor to kill one. As a certain Cherokee legend demonstrates, you simply don’t mess with an eagle. One night, according to The Eagle’s Revenge as recounted on the website FirstPeople.us, a hunter kills an eagle that he finds eating a deer hung on the drying pole. The following day seven warriors are felled mid-dance by seven whoops from a warrior who enters in the middle of the ceremony. The tribe later learns that it was the eagle’s brother, come to avenge the death.

The Coyote

Most commonly viewed as the trickster by many tribes, the coyote figure is also called Isily by the Cahuilla, Yelis by the Alsea and Old Man Coyote by the Crow Tribe, which views the animal as both creator and trickster. Regarded by some tribes as a hero who creates, teaches and helps humans, the coyote also demonstrates the dangers of negative behaviors such as greed, recklessness and arrogance in other tribes.

Overall, the coyote is often referred to as a creature of both folly and intelligence that seeks to fulfill its own needs at the expense of others. The coyote is also known as a master of disguise.

The Buffalo

As one of the most important life sources for the Plains tribes, the American buffalo, or bison, is a sacred and strong giver of life. Their horns and hides were used as sacred regalia during ceremony. They are also tied to creation, medicine and bringers of sacred messages by the ancestors such as White Buffalo Calf Woman, the bearer of the peace pipe to the Lakota people.

In an Apache story, a powerful being by the name of Humpback had always kept the buffalo from the tribes of Earth, thanks to Coyote, who tricked Humpback and his son into believing that he was a dog, waited for them to fall asleep and then barked to scare the buffalo. The buffalo in turn trampled Humpback’s house flat, which allowed the bison to roam the Earth and feed the people.

The Raven

Another trickster, the raven is a big part of many tribes including the Tlingit of Alaska, who tell many stories about how the raven created the stars and the moon. The raven is the creator god of Gwich’ in mythology—mischievous and loud, and in many ways a sarcastic troublemaker, he is also known as a thief.

In one Tlingit story the raven changes himself into a small piece of dirt, and a young girl, the daughter of a rich man, swallows the transformed raven in a drink. The girl has a child, who cries until bundles are opened to create the stars and the moon. Finally the child takes the bundle, which is in fact daylight, and the raven is revealed.

In the trickster vein, this one hilarious, the Raven places dog feces near the rear end of his brother-in-law in order to trick him. While he is distracted, the Raven takes all of the water in his brother-in-law’s nearby spring.

The Turtle

Known as the carrier of Turtle Island by the Great Spirit, the turtle plays a fundamental role in the creation stories of many East Coast tribes. The name Turtle Island is literal: Having placed a large amount of dirt on a great turtle’s back in order to create North America, the Creator designated the turtle as its eponymous caretaker.

While Plains tribes associate the turtle with long life and fertility, other tribes associate the turtle with healing, wisdom, spirituality and patience. The Hopi know the turtle spirit as Kahaila, while it is Mikcheech to the Micmac and Tolba to the Abenaki.

Ancient bobcat buried like a human being

Science Magazine By David Grimm Jul. 2, 2015

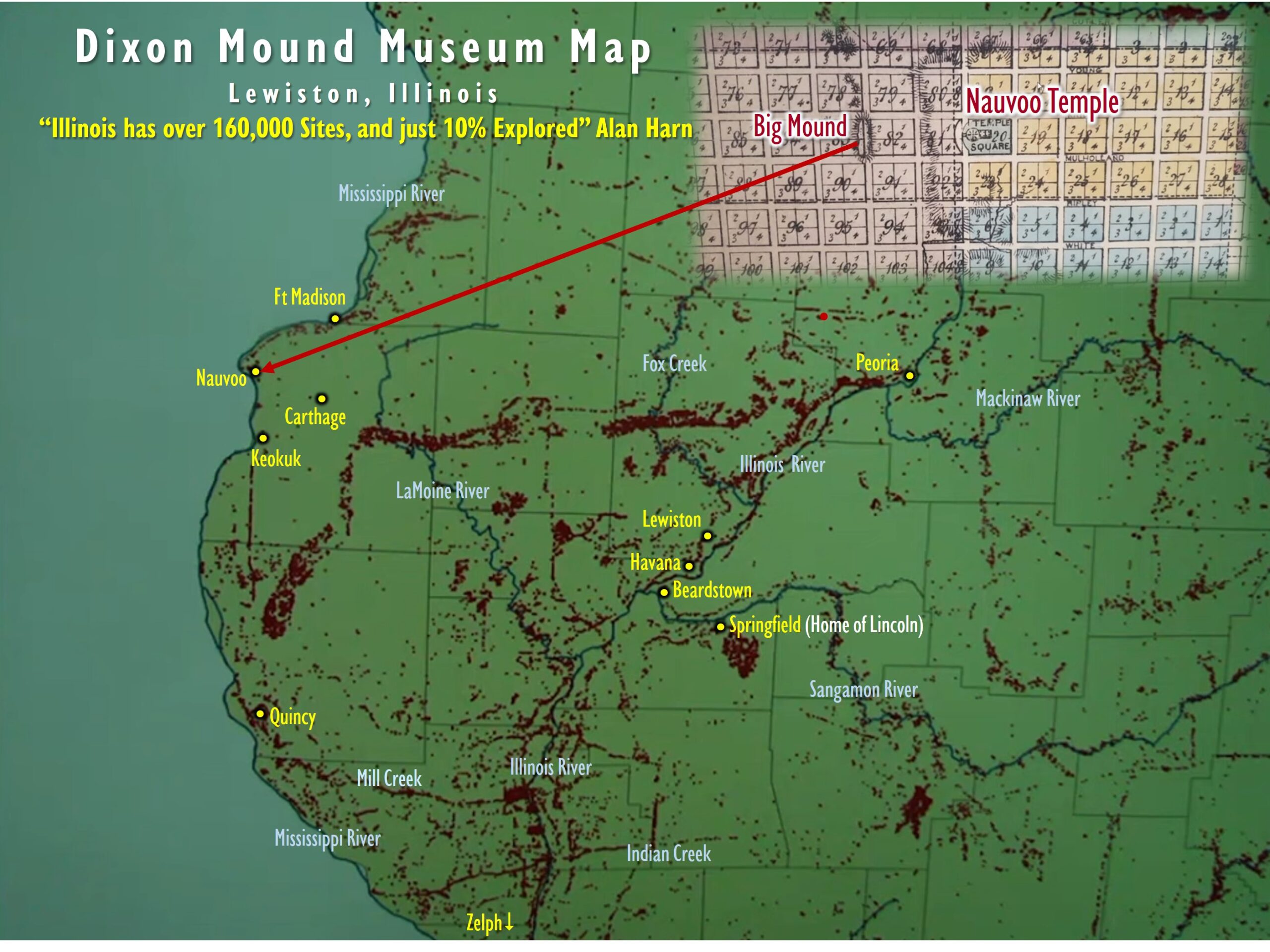

About 2000 years ago in what is today western Illinois, a group of Native Americans buried something unusual in a sacred place. In the outer edge of a funeral mound typically reserved for humans, villagers interred a bobcat, just a few months old and wearing a necklace of bear teeth and marine shells. The discovery represents the only known ceremonial burial of an animal in such mounds and the only individual burial of a wild cat in the entire archaeological record, researchers claim in a new study. The villagers may have begun to tame the animal, the authors say, potentially shedding light on how dogs, cats, and other animals were domesticated.

“It’s surprising and marvelous and extremely special,” says Melinda Zeder, a zooarchaeologist at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. But Zeder, who was not involved in the study, says it’s unclear whether these people treated the bobcat as a pet or invested the animal with a larger spiritual significance.

The mound is one of 14 dirt domes of various sizes that sit on a bluff overlooking the Illinois River, about 80 kilometers north of St. Louis. Their builders belonged to the Hopewell culture, traders and hunter-gatherers who lived in scattered villages of just a couple of dozen individuals each and created animal-inspired artwork, like otter-shaped bowls and ceramics engraved with birds. “Villages would come together to bury people in these mounds,” says Kenneth Farnsworth, a Hopewell expert at the Illinois State Archaeological Survey in Champaign. “It was a way to mark the area as belonging to your ancestors.”

Archaeologists rushed to excavate the mounds in the early 1980s because of an impending highway project. When they dug into the largest one—28 meters in diameter and 2.5 meters high—they unearthed the bodies of 22 people buried in a ring around a central tomb that contained the skeleton of an infant. They also discovered a small animal interred by itself in this ring; marine shells and bear teeth pendants carved from bone lay near its neck, all containing drill holes, suggesting they had been part of a collar or necklace. The Hopewell buried their dogs—though in their villages, not in these mounds—and the researchers assumed the animal was a canine. They placed the remains in a box, labeled it “puppy burial,” and shelved it away in the archives of the Illinois State Museum in Springfield.

Decades later, Angela Perri realized that the team had gotten it wrong. A Ph.D. student at the University of Durham in the United Kingdom, Perri was interested in ancient dog burials and came across the box in 2011 while doing research at the museum. “As soon as I saw the skull, I knew it was definitely not a puppy,” says Perri, now a zooarchaeologist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany. “It was a cat of some kind.”

When Perri analyzed the bones, she found that they belonged to a bobcat, likely between 4 and 7 months old. The skeleton was complete, and there were no cut marks or other signs of trauma, suggesting to Perri that the animal had not been sacrificed. When she looked back at the original excavation photos, she saw that the bobcat had been carefully placed in its grave. “It looked respectful; its paws were placed together,” she says. “It was clearly not just thrown into a hole.”

When Perri told Farnsworth, he was floored. “It shocked me to my toes,” he says. “I’ve never seen anything like it in almost 70 excavated mounds.” Because the mounds were intended for humans, he says, somebody bent the rules to get the cat buried there. “Somebody important must have convinced other members of the society that it must be done. I’d give anything to know why.”

Perri, who reports the discovery with Farnsworth and another colleague this week in the Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology, has her suspicions. The pomp and circumstance of the burial, she says, “suggests this animal had a very special place in the life of these people.” And the age of the kitten implies that the villagers brought it in from the wild—perhaps as an orphan—and may have tried to raise it. Bobcats, she notes, are only about twice the size of a housecat and are known to be quite tamable. The necklace seals the deal for her. She thinks it may have been a collar, a sign that the animal was a cherished pet. “This is the closest you can get to finding taming in the archaeological record,” says Perri, who believes the find provides a window into how other animals—whether they be dogs or livestock—were brought into human society and domesticated. “They saw the potential of this animal to go beyond wild.”

That’s certainly possible, Zeder says. “Taming can be a pathway to domestication.” But she cautions against reading too much into one find. “It’s just a single specimen in a very special context. Talking about domestication might be stretching it.” If the Hopewell really viewed the bobcat as a pet, she says, they would probably have buried it in the same place as their dogs. Instead, she suspects that the cat may have had a symbolic status, perhaps representing a connection to the spiritual world of the wild. “This could be more of a cosmological association.”

Jean-Denis Vigne, a zooarchaeologist at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, calls the find “a very unique and important discovery.” He says it reminds him of hunter-gatherer societies in South America that bring young monkeys and other wild animals into their homes, rearing and sometimes breastfeeding them as a way to thank nature for bountiful game and crops. Still, Vigne says he’s not aware of people burying these animals. “There’s a lot that still needs to be explored.”

Unfortunately, further work on the bobcat may not be possible. The museum where the bones are housed is facing a shutdown due to state budget cuts, and Perri says she can no longer access the samples. Public groups and museum staff are fighting hard to stop the closure, she says.