Just as the Book of Mormon tells the story of two main societies at war Nephites vs. Lamanites, there are many instances historically of the same thing as some are called the Iroquois vs. the Algonquian, or the Tallegwi vs the Leni-Lape, or the Cherokee vs the Delaware. These tribes seem to always be at war with each other. The names on the list below (Map 1, 2) each are various sub-tribes under various groups of people. Sometimes in history writers have used various names for the same group of people without understanding the differences.

Leni-Lape = Delaware = Chipewa = Miqmak = ALGONQUIAN!

Alleghewi = Tallegwi = Tsalagi = Cherokee = Allegheny = IROQUOIS!

“There can be no reasonable doubt that the Alleghewi or Tallegwi, who have given their name to the Alleghany River and Mountains, were the mound-builders. The destiny which ultimately befell the Mound-builders can be inferred from what was known of the fate of the Huron themselves in their final was with the Iroquois. The greater portion of the Huron people were exterminated, and their towns reduced to ashes. Of the survivors many were received and adopted among the conquerors. A few fled to the east and sought protection from the France.” Archaeological History of Ohio: The Mound builders and Later Indians pg 438

“It may be considered as beyond dispute that the Cherokees are a branch or off-shoot of the Huron-Iroquois family. Their language proves it. “The striking fact has become evident that the course of the migration of the Huron-Iroquois family has been from eastern Canada, on the Lower St. Lawrence, to the mountains of northern Alabama.” Archaeological history of Ohio : The Mound builders and later Indians / by Gerard Fowke.

Talmage and Mills

“This evening at the hotel I had a long and profitable consultation with Professor Wm. C. Mills, State Archaeologist of Ohio. He is continuing his splendid work of exploration in the Ohio mounds, and I went over with him again the remarkable agreement between his deductions and the Book of Mormon story. He has reached the following (10) conclusions: The area now included within the political boundaries defining the State of Ohio was once inhabited by two distinct peoples, representing two cultures, a higher and a lower.

These two classes were contemporaries; in other words, the higher and the lower culture represented distinct phases of development existing at one time and in contiguous sections, and furnish in no sense an instance of evolution by which the lower culture was developed into the higher.

These two cultural types or distinct peoples were generally in a state of hostility one toward the other, the lower culture being more commonly the aggressor and the higher the defender.

During limited periods, however, the two types, classes, or cultures, lived in a state of neutrality, amounting in fact to friendly intercourse.

The numerous exhumations of human bones demonstrate that the people of the lower type, if not indeed both cultures, were very generally affected by syphilis, indicating a prevalent condition of lasciviousness.

Their (are) two peoples or cultures…the lower culture was most commonly the assailing party, while the people of the higher type defended as best they could but in general fled.

As a further consequence of this belligerent status they buried their dead, with or without previous cremation, in such condition as to admit of expeditious covering up of the cemeteries by the heaping of earth over the sepulchers [sic], in which hurried work the least skilled laborers and even children could be employed.

From a careful collating of data it is demonstrated that the general course of migration through the area now defined as the State of Ohio was inward from the west and outward toward the east.

Professor Mills states that no definite data as to the age of these peoples have as yet been found, but that the mounds may date back a few hundred years or even fifteen hundred or more.

Several years ago I placed a Book of Mormon in the hands of Professor Mills and, while he is reticent as to the parallelism of his discoveries and the Book of Mormon account, he is impressed by the agreement.” James E. Talmage 20 May 1917 See copies from William Mills 1914 publication called Archaeological Atlas of Ohio

The Delaware Nation of Lamanites by Jonathan Neville |

Oliver Cowdery wrote a letter dated April 8, 1831, from Jackson County, Missouri, to the Saints in Kirtland. He described some of the events of the mission to the Lamanites. I think everyone agrees that “early” members of the Church believed the American Indians in the U.S. and its territories were Lamanites. Here, Oliver refers to the Delaware Indians as the “deleware Nation of Lamanites.”

That fits pretty well with what the Lord said in D&C 28, 30 and 32.

_______________

Here is a short history of the Delaware nation:

__________________

Among other things, Oliver wrote:

“I this day received heard from the deleware Nation of Lamanites by the man who is employed by government a smith for that Nation he believes the truth and says he tha[n]ks God he does believe and also says that he shall shortly be baptized which I pray God may be the case for truly my brethren he is a man he also says that we have put more into the lamenites during the short time we we were permited to be with them (which was but a few days[)] then all the devels in the infernal pit and and and all the men on earth can get out of them in four generations he tells me that, that evry Nation have now the name of Nephy who is the son of Nephi & handed down to this very generation, there is only a part of that Nation here now but the remainder are expected this spring the principle chief says he believes evry word of the Book & there are many <more> in the Nation who believe and we understand there are many among the Shawnees who also believe & we trust that when the Lord shall open the <our> way we shall have glorious times for truly my brethren my heart sorrows for them for they are cast out & dispised and know not the God in whom they should trust we have traveld about in this country considerable and proclaimed repentence and very <many> are very anxious serious & honest.”

You can see the entire letter here: http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/letter-from-oliver-cowdery-8-april-1831/1 Source: Book of Mormon Wars

North American Indian Tribes

One of the most important non-LDS books which supports the Heartland Book of Mormon geography! Old World Roots of the Cherokee: How DNA, Ancient Alphabets and Religion Explain the Origins of America’s Largest Indian Nation, by Dr. Donald N. Yates provides the most stunning new research validating the Heartland Model. The Cherokee share DNA and cultural similarities with ancient Jewish populations. This blockbuster book is critical for the true “remnant” of the Book of Mormon

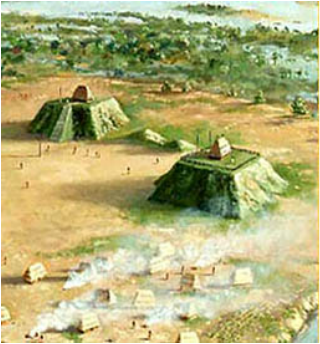

THE CITIES, FORTIFICATIONS AND EARTHWORKS OF THE TALLIGEWI

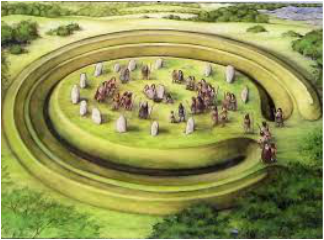

| Heckewelder wrote about the Talligewi earthworks found in the area of Lake Erie where he believed the Talligewi went after being defeated by the Delaware and Iroquois. (See map 3 below) He further stated that he was shown earthen mounds near Sandusky, Ohio, where there were found hundreds of slain Talligewi warriors buried. The Talligewi were said to have regularly built earthen fortifications, that were so strong that the Talligewi defended and protected themselves that the Delaware had to seek assistance from the Iroquois. The fortifications and the power of the Talligewi were so strong that it took the war through many years, The Talligewi were finally defeated and the Talligewi survivors fled. For many years the Talligewi the were at the Great Lakes began migrating south through what was believed is now Indiana. The Talligewi set up settlements east of the Fish River which Heckewelder thought was the Mississippi River. Some information that Mooney wrote in his book stated that the river was called the Big Fish River and the river ran north to south. Some say that if in Indiana and the river ran south, and included lakes and marsh lands, the river may have been the Old Kankakee River, which ran through Indiana. If in fact the river was the Kankakee the Kankakee marsh lands and lakes would have been in St. Joseph County, Indiana. Archaeologists have discovered several ancient burial mounds and ceremonial mounds in Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee which seem to prove, that this country was formerly inhabited by a nation farther advanced than other Indians that were migrating south. R.S. Cotterill, in writing his “History of Pioneer Kentucky” (which, of necessity included Southern Indiana in the area of the falls of the Ohio), remarked on pre-Columbian Kentucky: “There are many traditions to indicate, and a few shreds of evidence to prove, that in the far past that Indiana and Kentucky supported an advanced and extensive civilization. Here they built huge mounds for fortifications, for burial places and for temples |

The Lenape-Allegewi War: A Native American Titanomachy

“By the time Europe realized the world wasn’t flat and decided to capitalize on its newly discovered career in real estate speculation, numerous civilizations had risen and fallen in the New World, including a few that were highly literate. This of course, required us to burn all their books and reduce the folk traditions of the “savages” to pagan mythology. When we inconveniently ran across oddly sophisticated, 5000 year old mound complexes stretching across vast swaths of territory, we (1) assumed that the relatively low technology natives or their ancestors could not possibly have been responsible for them (self-servingly muttering about the lost 13th Tribe of Israelites, or in more recent times, Vikings), and (2) if they in any way related to the indigenous populations we encountered, the peoples remaining were the product of collapse, dissolution, and regression. Our teleological inclinations abhor discontinuity, thus when disparate native tribes concurred that a sophisticated civilization of “giants” with serious earthworks construction chops dominated the area until a brutal war eradicated them, historians exerted a great deal of effort trying to prove that it was a fairy tale about the ultimate origins of the Cherokee. The indigenous explanation was that a monstrous tribe called the Allegewi (sometimes Tallegwi, preserved in the names of the Alleghany Mountains and River) were driven from the eastern side of the Mississippi in a genocidal war by an alliance of the migrating Lenni-Lenapes and Mengwe. Unsurprisingly, this hack and slash history of the founders of our respective civilizations battling giants to the last man, is repeated cross-culturally, from the Aesir-Vanir Wars of Teutonic mythology, to the South Indian Asura-Deva War, to the Greek Titanomachy. As a species, we seem to have spent many of our formative years hunting down giants.

By the time Westerners encountered the Lenni-Lenape, they were happily settled in territory in what is modern day Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, and Delaware (hence they are more commonly referred to as “the Delaware tribe”), but Lenni-Lenape legends steadfastly maintain that their ancestors originated from the northwestern shores of the Mississippi River, eventually moving into the Ohio Valley looking for more hospitable climes. The problem is that as they scouted across the Mississippi, they noticed the land was already occupied.

According to tradition handed down from their ancestors, the Lenni-Lenapes resided for many centuries in a very distant country, in the western part of the American continent. Having resolved to move eastward, they set out in a body in search of a new home, and after a long journey and many nights encampment (i.e., half of one year at a place), they reached the Sipee (Mississippi), where they fell in with another nation, the Mengwe, or Iroquois, who had also emigrated from a distant country for the same purpose. The region east of the Mississippi was occupied by the Allegewi (Alleghany), a powerful and partially civilized people, having numerous large towns defended by regular fortifications and entrenchments. In this country the Lenape, on their arrival, asked to settle. This request was denied by the Allegewi, but permission was granted to pass through the territory, and seek a settlement further eastward. No sooner had they commenced to cross the Mississippi, however, than the Allegewi, perceiving the vast number of the Lenapes, furiously attacked them. The result of this treachery was a long and bloody war between the Lenapes and their allies, the Mengwe, on the one side, and the Allegewi on the other. The latter, after a protracted contest, finding themselves unable to make head against the formidable alliance, and that their very existence, as a tribe, was threatened, abandoned their ancient seats and fled down the Mississippi, from whence they never again returned (Waring, 1889, p136-137).

Migration and displacement is pretty much the history of the human race in a nutshell. Bands of unruly folks wander about until they find some prime territory, and determine to grab it, knock some heads and take some names. The Mengwe, understood to be an Iroquoian predecessor, tell similar tales that concur with the Lenni-Lenape version of events. Curiously, these legends emphasize that the Allegewi were not just some unfortunate tribe that happened to be in the way, rather that they were warlike giants, far larger than your average Lenape.

And now the spies, who had been sent forward for the purpose of reconnoitering, returned. They had seen many things so strange, that when they reported them, our people half-believed them to be dreams, and for a while regarded them but as the songs of birds. They told, that they had found the further bank of the River of Fish inhabited by a very powerful people, who dwelt in great villages, surrounded by high walls. They were very tall—so tall that the head of the tallest Lenape could not reach their arms, and their women were of higher stature and heavier limbs than the loftiest and largest man in the confederate nations. They were called the Allegewi, and were men delighting in red and black paint, and the shrill war-whoop, and the strife of the spear. Such was the relation made by the spies to their countrymen. This report of the spies increased the fears and dissatisfaction of the Lenapes to such a height, that part agreed to remain in the lands in which they then were, and not to attempt to cross the river occupied by so many hostile warriors. But the greater part declared that they were men, and rather than turn back from a foe, however strong, or leave a battlefield without a blow or a war-whoop, they would march to certain death, and leave their bones in a hostile camp (Jones, 1830, p160-161).

Early European explorers in Pennsylvania, New York, and Maryland, running across tribes thought to have been Iroquoian in origin, also recorded the indigenous narrative for their presence, noting both the purported monstrous stature of the Allegewi as well as their talent for defensive engineering. It was also said that the Allegewi dominated the local Algonquin tribes and that an isolated remnant of holdouts were holed up in a mountain fortress as late as the 17th Century A.D.

The name Conestogo seems to have applied to this tribe of Indians long before Penn applied it to them. Evidently the stream and township originally may have taken their name from them. They seem to have some features in common with the Allegewi. They were of gigantic size, (Captain John Smith, in 1608, when on an exploring expedition at the mouth of the Susquehanna, met representatives of this tribe whom he described as of gigantic stature and of magnificent proportions); they were also a warrior tribe, having fortifications and entrenchments for defense; (this we will find later was not a general characteristic of the Indians), and they were renowned in the days of their glory for their valor and undaunted bravery “who, when fighting, never fled, but stood like a wall as long as there was one remaining.” Their palisaded town was on a steep mountain, difficult of access. They had guns and small cannon for defense and were practically impregnable in their mountain fastness. Isolated as they were, they kept the various surrounding Algonquin tribes in complete subjection, so that they did not dare to go to war against them. At the close of the Sixteenth century they were at war with the Mohawks, who suffered almost complete annihilation at their hands. In May, 1663, they were engaged with the Senecas, and with the odds sixteen to one, a little band of one hundred of them (the main body having been absent on an expedition to Maryland), defended themselves in their fort, then sallied out in vigorous onslaught, routed the enemy and put them to flight. Later they engaged with the Iroquois, in league, in as furiously contested warfare as history ever chronicled or human passion and the glory of arms ever contrived. Their encounters were, indeed, desperate, and though their forces were much reduced by smallpox, they were frequently victorious against overwhelming odds. They were finally defeated and conquered. In 1675 the Iroquois, urged and aided by Maryland and “Virginia troops under Major Trueman and Colonel Washington (grandfather of General Washington), who perpetrated, at this time, an act of treachery that later was responsible for Bacon’s rebellion, reduced the Susquehannas to complete subjection and forced them to return to their original lands along the Susquehanna (Lancaster County, 1917, p90).

The small number of surviving Allegewi, ravaged by the combined forces of the Lenni-Lenape and Mengwe, were said to have escaped south along the Mississippi, seeking a last refuge among the southerly tribes.

The traditions of the Lenni-Lenape, another Algonquian tribe, state that they came from the north, doubtless west of Lake Superior, “where it was cold and froze and stormed, to possess milder lands abounding in game.” Fighting their way, they sojourned in the land of firs, and later arrived on the plains of the buffalo land. Then they “longed for the rich east-land” and their passage across the Mississippi in south Minnesota was contested by the Tallegewi (Tsalagi or Cherokee); these were a tall people who had many large towns and fortifications; they were probably the effigy-builders of the Wisconsin-Minnesota-Iowa region of the old mound-builders. Those who crossed the river, being assisted by the Mengwe (an Iroquoian tribe, Hurons?), eventually expelled the Tallegewi, who fled down the Mississippi. Most of the Lenape remained in the Mississippi valley, but some finally settled in the eastern states, part of whom were known as Delaware (Haddon, 1919, p87).

It has been suggested that the last Allegewi, who both Iroquoian and Lenni-Lenape traditions associate with the ancient “Mound-Builders” were absorbed by the more southern Choctaws, Chickasaws, and Creeks. The nearby Cherokee maintain that they originated in the Ohio Valley, fleeing south, and scholars were quick to suggest that the Cherokee tribes represented the amalgamation of the mythical Allegewi with the Choctaw. Now while the Cherokee were no doubt big and tough, they were not giants, but since the sober historian cannot allow for the possibility that giants ever walked the earth, this was greedily seized on as a perfectly reasonable explanation for what is partially recounted in Lenni-Lenape and Iroquoian histories (that is, they kicked some keister and made a successful land grab, herding the decimated Allegewi south), but conveniently ignores multiple indigenous viewpoints that emphasize the Allegewi were a sophisticated race of mound-building giants. This is all wrapped up in a neat little teleological package.

The traditions of the Delawares preserved the remembrance of the Talligew or Tallegewi, a powerful nation whose western borders extended to the Mississippi, over whom they, in conjunction with the fierce warrior race of Wyandots or Iroquois, triumphed. The old name of the Mound-Builders is believed to survive, in modified form, in that of the Alleghany Mountains and River; and the Chatta-Muskogee tribes, including the Choctaws, Chickasaws, Creeks, and other southern Indians of the same stock, are supposed to represent the ancient race. The broad fertile region stretching southward from the Appalachian Mountains to the Gulf of Mexico must have attracted settlers from earliest times. It was latterly occupied by various tribes of this Chatta-Muskogee stock; but intermingled with others speaking essentially different languages, and supposed to be the descendants of the older occupants of the region on whom the Tallegewi intruded when driven out of the Ohio valley. The Cherokees preserved a tradition of having come from the upper Ohio. They have been classed by the Washington ethnologists as a distant branch of the Iroquois stock; but Mr. Hale, finding their grammar mainly Huron-Iroquois, while their vocabulary is largely derived from another source, ingeniously infers that one portion of the despairing Talligewi may have cast in their lot with the conquering race, as the Tlascalans did with the Spaniards in their war against the Aztecs. Driven down the Mississippi till they reached the country of the Choctaws, they, mingling with friendly tribes, became the founders of the Cherokee nation (Wilson, 1892, p103).

It would be mighty inconvenient for historians if civilized giants rose and fell in North America long before Western Europe got its grubby little hands on it. Or that pockets of giants in Scandinavia, India, and Greece struggled futilely against the onslaught of diminutive, upstart Homo sapiens. Such notions run counter to the continuous ascendancy of man, as it suggests that the history of sentience and civilization may not be the sole preserve of our particular subspecies of wise ape. It is nearly impossible to understand the full import for the future of what happens now, but the history of hindsight is less about reality, than aesthetic exercise in appreciation of our current position at the top of the Great Chain of Being, or as Voltaire said, “There certainly is no useful or entertaining history but the history of the day. All ancient histories, as one of our wits has observed, are only fables that men have agreed to admit as true; and with regard to modern history, it is a chaos out of which it is impossible to make anything.” The Lenape-Allegewi War: A Native American Titanomachy

References

Haddon, Alfred C. 1855-1940. The Wanderings of Peoples. Cambridge: The University press, 1919.

Jones, James Athearn, 1791-1854. Traditions of the North American Indians. being a second and revised edition of “Tales of an Indian camp.” London: H. Colburn and R. Bentley, 1830.

Lancaster County Historical Society (Pa.). Historical Papers And Addresses of the Lancaster County Historical Society. Lancaster, Pa: [Lancaster County Historical Society], 1917.

Waring, Clara Ingersoll. Faun-Fa: A Story of the Catskill Mountains In Four Parts. Detroit: Ostler Printing Co., 1889.

Wilson, Daniel, Sir, 1816-1892. The Lost Atlantis: And Other Ethnographic Studies. Edinburgh: D. Douglas, 1892.

THE PROBLEM OF THE OHIO MOUNDS.

BY CYRUS THOMAS. Washington Government Printing Office 1889

“No other ancient works of the United States have become so widely known or have excited so much interest as those of Ohio. This is due in part to their remarkable character but in a much greater degree to the “Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley,” by Messrs. Squier and Davis, in which these monuments are described and figured.

The constantly recurring question, “Who constructed these works?” has brought before the public a number of widely different theories, though the one which has been most generally accepted is that they originated with a people long since extinct or driven from the country, who had attained a culture status much in advance of that reached by the aborigines inhabiting the country at the time of its discovery by Europeans.

The opinion advanced in this paper, in support of which evidence will be presented, is that the ancient works of the State are due to Indians of several different tribes, and that some at least of the typical works, were built by the ancestors of the modern Cherokees. The discussion will be limited chiefly to the latter proposition, as the limits of the paper will not permit a full presentation of all the data which might be brought forward in support of the theory, and the line of argument will be substantially as follows:

First. A brief statement of the reasons for believing that the Indians were the authors of all the ancient monuments of the Mississippi Valley and Gulf States; consequently the Ohio mounds must have been built by Indians.

Second. Evidence that the Cherokees were mound builders after reaching their historic seats in East Tennessee and western North Carolina. This and the preceding positions are strengthened by the introduction of evidence showing that the Shawnees were the authors of a certain type of stone graves, and of mounds and other works connected therewith.

Third. A tracing of the Cherokees, by the mound testimony and by tradition, back to Ohio

Fourth. Reasons for believing that the Cherokees were the Tallegwi of tradition and the authors of some of the typical works of Ohio.

THE CHEROKEES AND THE TALLEGWI.

The ancient works of Ohio, with their “altar mounds,” “sacred enclosures,” and “mathematically accurate” but mysterious circles and squares, are still pointed to as impregnable to the attacks of this Indian theory. That the rays of light falling upon their origin are few and dim, is admitted; still, we are not left wholly in the dark.

If the proof be satisfactory that the mounds of the southern half of the United States and a portion of those of the Upper Mississippi Valley are of Indian origin, there should be very strong evidence in the opposite direction in regard to those of Ohio to lead to the belief that they are of a different race. Even should the evidence fail to indicate the tribe or tribes by whom they were built, this will not justify the assertion that they are not of Indian origin.

If the evidence relating to these works has nothing decidedly opposed to the theory in it, then the presumption must be in favor of the view that the authors were Indians, for the reasons heretofore given. The burden of proof is on those who deny this, and not on those who assert it.

It is legitimate, therefore, to assume, until evidence to the contrary is produced, that the Ohio works were made by Indians.

The geographical position of the defensive works connected with these remains indicates, as has been often remarked by writers on this subject, a pressure from northern hordes which finally resulted in driving the inhabitants of the fertile valleys of the Miami, Scioto, and Muskingum, southward, possibly into the Gulf States, where they became incorporated with the tribes of that section. [Footnote: Force: “To what race did the mound—builders belong?” p. 74, etc.] If this is assumed as correct it only tends to confirm the theory of an Indian origin.

But the decision is not left to mere assumption and the indications mentioned, as there are other and more direct evidences bearing upon this point to be found in the works of art and modes of burial in this region. That the mound—builders of Ohio made and used the pipe is proven by the large number of pipes found in the mounds, and that they cultivated tobacco may reasonably be inferred from this fact.

The general use of the pipe among the mound—builders is another evidence of their relation to the Indians; while, on the other hand, this fact and the forms of the pipes indicate that they were not connected with the Nahua, Maya, or Pueblo tribes.

Although varied indefinitely by the addition of animal and other figures, the typical or simple form of the pipe of the Ohio mound— builders appears to have been that represented by Squier and Davis [Footnote: Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, 1847, p. 179.] in their Fig. 68; and by Rau in Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, No. 287. [Footnote: 1876, p. 47, Fig. 177.] The peculiar feature is the broad, flat, and slightly—curved base or stem, which projects beyond the bowl to an extent usually equal to the perforated end. Reference has already been made to the statement by Adair that the Cherokees were accustomed to carve, from the soft stone found in the country, “pipes, full a span long, with the fore part commonly running out with a short peak two or three fingers broad and a quarter of an inch thick.” But he adds further, as if intending to describe the typical form of the Ohio pipe, “on both sides of the bowl lengthwise.” This addition is important, as it has been asserted [Footnote: Young Mineralogist and Antiquarian, 1885, No. 10. p. 79.] that no mention can be found of the manufacture or use of pipes of this form by the Indians, or that they had any knowledge of this form.

E. A. Barber says: [Footnote: Am. Nat., vol. 16, 1882, pp. 265, 266]

The earliest stone pipes from the mounds were always carved from a single piece, and consist of a flat curved base, of variable length and width, with the bowl rising from the center of the convex side (Anc. Mon., p. 227).

The typical mound pipe is the Monitor form, as it may be termed, possessing a short, cylindrical urn, or spool—shaped bowl, rising from the center of a flat and slightly—curved base. [Footnote: For examples of this form see Rau: Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, No. 287, p. 47, Fig. 177.]

This 36 page softcover book, RED MAN’S ORIGIN, provides the earliest and most complete account of the story of the origins and migrations of the Cherokee people, as first told by Native Cherokee George Sahkyah Sanders; translated and recorded by Cornsilk (William Eubanks – a Cherokee) from the recitation in Cherokee in the 1890s in Indian Territory. This faithful reproduction by Cherokee Native Donald Panther Yates provides unique insights into Cherokee origin lore and history.

Accepting this statement as proof that the “Monitor” pipe is generally understood to be the oldest type of the mound—builders’ pipe, it is easy to trace the modifications which brought into use the simple form of the modern Indian pipe. For example, there is one of the form shown in Fig. 5, from Hamilton County, Ohio; another from a large mound in Kanawha Valley, West Virginia; [Footnote: Science. 1884, vol. 3, p. 619.] several taken from Indian graves in Essex County, Mass.; [Footnote: Abbott, Prim. Industry, 1881, Fig. 313, p. 319; Bull. Essex Inst., vol. 3, 1872, p. 123.] another found in the grave of a Seneca Indian in the valley of the Genesee; [Footnote: Morgan, League of the Iroquois, p. 356.] and others found by the representatives of the Bureau of Ethnology in the mounds of western North Carolina.

Fig. 5. Pipe from Hamilton County, Ohio.

So far, the modification consists in simply shortening the forward projection of the stem or base, the bowl remaining perpendicular. The next modification is shown in Fig. 6, which represents a type less common than the preceding, but found in several localites, as, for example, in Hamilton County, Ohio; mounds in Sullivan County, east Tennessee (by the Bureau); and in Virginia. [Footnote: Rau: Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, No. 287, p. 50, Fig. 190.] In these, although retaining the broad or winged stem, we see the bowl assuming the forward slope and in some instances (as some of those found in the mounds in Sullivan County, Tenn.) the projection of the stem is reduced to a simple rim or is entirely wanting.

Fig. 6. Pipe from Hamilton County, Ohio.

Fig. 7. Pipe from Sullivan County, Tennessee.

The next step brings us to what may be considered the typical form of the modern pipe, shown in Fig. 8. This pattern, according to Dr. Abbott, [Footnote: Prim. Industry, 1861, p. 329.] is seldom found in New England or the Middle States, “except of a much smaller size and made of clay.” He figures one from Isle of Wight County, Va., “made of compact steatite.” A large number of this form were found in the North Carolina mounds, some with stems almost or quite a foot in length.

Fig. 8. Pipe from Caldwell County, North Carolina.

It is hardly necessary to add that among the specimens obtained from various localities can be found every possible gradation, from the ancient Ohio type to the modern form last mentioned. There is, therefore, in this peculiar line of art and custom an unbroken chain connecting the mound—builders of Ohio with the Indians of historic times, and in the same facts is evidence, which strengthens the argument, disconnecting the makers from the Mexican and Central American artisans.

As this evidence appears to point to the Cherokees as the authors of some of the typical mounds of Ohio, it may be as well to introduce here a summary of the data which bear upon this question.

Reasons which are thought well—nigh conclusive have already been presented for believing that the people of this tribe were mound— builders, and that they had migrated in pre—Columbian times from some point north of the locality in which they were encountered by Europeans. Taking up the thread of their history where it was dropped, the following reasons are offered as a basis for the conclusion that their home was for a time on the Ohio, and that this was the region from which they migrated to their historic locality.

As already shown, their general movement in historic times, though limited, has been southward. Their traditions also claim that their migrations previous to the advent of the whites had been in the same direction from some point northward, not indicated in that given by Lederer, but in that recorded by Haywood, from the valley of the Ohio. But it is proper to bear in mind that the tradition given by Lederer expressly distinguishes them from the Virginia tribes, which necessitates looking more to the west for their former home. Haywood connects them, without any authority, with the Virginia tribes, but the tradition he gives contradicts this and places them on the Ohio.

The chief hostile pressure against them of which we have any knowledge was from the Iroquois of the north. This testimony is further strengthened by the linguistic evidence, as it has been ascertained that the language of this tribe belongs to the Iroquoian stock. Mr. Horatio Hale, a competent authority on this subject, in an article on Indian migrations published in the American Antiquarian, [Footnote: Am. Antiquarian, vol. 5, 1883, p. 26] remarks as follows:

Following the same course of migration from the northeast to the southwest, which leads us from the Hurons of eastern Canada to the Tuscaroras of central North Carolina, we come to the Cherokees of northern Alabama and Georgia. A connection between their language and that of the Iroquois has long been suspected. Gallatin, in his “Synopsis of Indian Languages,” remarks on this subject: “Dr. Barton thought that the Cherokee language belonged to the Iroquois family, and on this point I am inclined to be of the same opinion. The affinities are few and remote, but there is a similarity in the general termination of the syllables, in the pronunciation and accent, which has struck some of the native Cherokees.”

The difficulty arising from this lack of knowledge is now removed, and with it all uncertainty disappears. The similarity of the two tongues, apparent enough in many of their words, is most strikingly shown, as might be expected, in their grammatical structure, and especially in the affixed pronouns, which in both languages play so important a part.

More complete vocabularies of the Cherokee language than have hitherto been accessible have recently come into possession of the Bureau of Ethnology, and their study serves to confirm the above conclusion that the Cherokees are an offshoot of Iroquoian stock.

On the other hand, the testimony of the mounds all taken together or considered generally (if the conclusion that the Cherokees were the authors of the North Carolina and East Tennessee mounds be accepted) seems to isolate them from all other mound—building people of that portion of the United States east of the Rocky Mountains. Nevertheless there are certain remains of art which indicate an intimate relation with the authors of the stone graves, as the engraved shells, while there are others which lead to the opinion that there was a more intimate relation with the mound—builders of Ohio, especially of the Scioto Valley. One of these is furnished by the stone pipes so common in the Ohio mounds, the manufacture of which appears also to have been a favorite pursuit of the Cherokees in both ancient and modern times. (Map 4)

In order to make the force of this argument clear it is necessary to enter somewhat further into details. In the first place, nearly all of the pipes of this type so far discovered have been found in a belt commencing with eastern Iowa, thence running eastward through northern Illinois, through Indiana, and embracing the southern half of Ohio; thence, bending southward, including the valley of the Great Kanawha, eastern Tennessee, and western North Carolina, to the northern boundary of Georgia. It is not known that this type in any of its modifications prevailed or was even in use at any point south of this belt. Pipes in the form of birds and other animals are not uncommon, as may be seen by reference to Pl. XXIII of Jones’s Antiquities of the Southern Indians, but the platform is a feature wholly unknown there, as are also the derivatives from it. This is so literally true as to render it strange, even on the supposition here advanced; only a single one (near Nashville, Tenn.), so far as known, having been found in the entire South outside of the Cherokee country.

This fact, as is readily seen, stands in direct opposition to the idea advanced by some that the mound—builders of Ohio when driven from their homes moved southward, and became incorporated with the tribes of the Gulf States, as it is scarcely possible such sturdy smokers as they must have been would all at once have abandoned their favorite pipe.

Some specimens have been found north and east of this belt, chiefly in New York and Massachusetts, but they are too few to induce the belief that the tribes occupying the sections where they were found were in the habit of manufacturing them or accustomed to their use; possibly the region of Essex, Mass., may prove to be an isolated and singular exception.

How can we account for the fact that they were confined to this belt except upon the theory that they were made and used by a single tribe, or at most by two or three cognate tribes? If this be admitted it gives as a result the line of migration of the tribe, or tribes, by whom they were made; and the gradual modification of the form indicates the direction of the movement.

In the region of eastern Iowa and northern Illinois, as will be seen by reference to the Proceedings of the Davenport Academy of Natural Sciences [Footnote: Vol. 1, 1876, Pl. IV.] and the Smithsonian Report for 1882, [Footnote: Smithsonian Report for 1882 (1884), Figs. 4—8, pp. 689—692] the original slightly—carved platform base appears to be the only form found.

Moving eastward from that section, a break occurs, and none of the type are found until the western border of Ohio is reached, indicating a migration by the tribe to a great distance. From this point eastward and over a large portion of the State, to the western part of West Virginia, the works of the tribe are found in numerous localities, showing this to have long been their home.

In this region the modifications begin, as heretofore shown, and continue along the belt mentioned through West Virginia, culminating in the modern form in western North Carolina and East Tennessee.

As pipes of this form have never been found in connection with the stone graves, there are just grounds for eliminating the Shawnees from the supposed authors of the Ohio works. On the other hand, the engraved shells are limited almost exclusively to the works of the Shawnees and Cherokees (taking for granted that the former were the authors of the box—shaped stone graves south of the Ohio and the latter of the works in western North Carolina and East Tennessee), but are wanting in the Ohio mounds. It follows, therefore, if the theory here advanced (that the Cherokees constructed some of the typical works of Ohio) be sustained, that these specimens of art are of Southern origin, as the figures indicate, and that the Cherokees began using them only after they had reached their historical locality.

Other reasons for eliminating the Shawnees and other Southern tribes from the supposed authors of the typical Ohio works are furnished by the character, form, and ornamentation of the pottery of the two sections, which are readily distinguished from each other.

That the Cherokees and Shawnees were distinct tribes, and that the few similarities in customs and art between them were due to vicinage and intercourse are well—known historical facts. But there is nothing of this kind to forbid the supposition that the former were the authors of some of the Ohio works. Moreover, the evidence that they came from a more northern locality, added to that furnished by the pipes, seems to connect them with the Ohio mound—builders. In addition to this there is the tradition of the Delawares, given by Heckewelder, which appears to relate to no known tribe unless it be the Cherokees. Although this tradition has often been mentioned in works relating to Indians and kindred subjects, it is repeated here that the reader may judge for himself as to its bearing on the subject now under consideration:

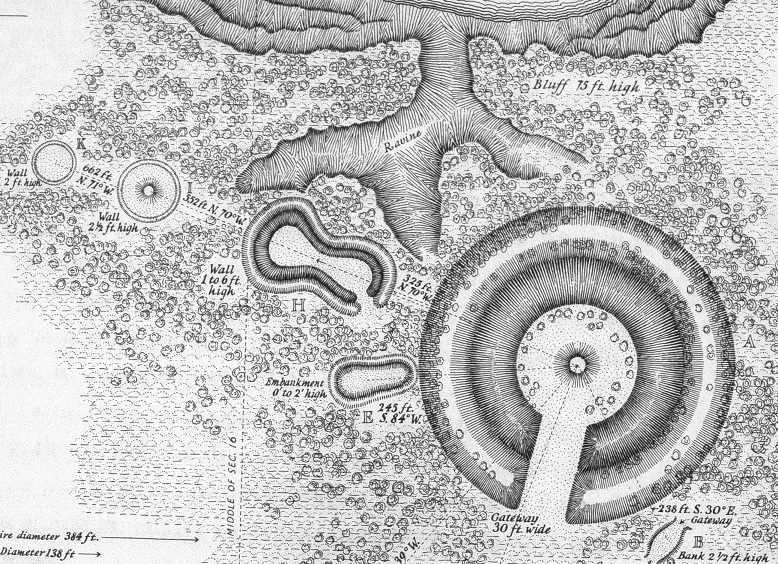

The Lenni Lenape (according to the tradition handed down to them by their ancestors) resided many hundred years ago in a very distant country in the western part of the American continent. For some reason which I do not find accounted for, they determined on migrating to the eastward, and accordingly set out together in a body. After a very long journey and many nights’ encampments [Footnote: “Many Nights’ encampment” is a halt of one year at a place.] by the way, they at length arrived on the Namaesi—Sipu, [Footnote: The Mississippi or The River of Fish; Namaes, a fish, and Sipu a river.] where they fell in with the Mengwe, [Footnote: The Iroquois, or Five Nations.] who had likewise emigrated from a distant country, and had struck upon this river somewhat higher up. Their object was the same with that of the Delawares; they were proceeding on to the eastward, until they should find a country that pleased them. The spies which the Lenape had sent forward for the purpose of reconnoitring, had long before their arrival discovered that the country east of the Mississippi was inhabited by a very powerful nation who had many large towns built on the great rivers flowing through their land. Those people (as I was told) called themselves Talligew or Tallgewi. Many wonderful things are told of this famous people. They are said to have been remarkably tall and stout, and there is a tradition that there were giants among them, people of a much larger size than the tallest of the Lenape. It is related that they had built to themselves regular fortifications or intrenchments, from whence they would sally out, but were generally repulsed. I have seen many of the fortifications said to have been built by them, two of which, in particular, were remarkable. One of them was near the mouth of the river Huron, which empties itself into the Lake St. Clair, on the north side of that lake, at the distance of about 20 miles northeast of Detroit. This spot of ground was, in the year 1776, owned and occupied by a Mr. Tucker. The other works, properly intrenchments, being walls or banks of earth regularly thrown up, with a deep ditch on the outside, were on the Huron River, east of the Sandusky, about six or eight miles from Lake Erie. Outside of the gateway of each of these two intrenchments, which lay within a mile of each other, were a number of large flat mounds in which, the Indian pilot said, were buried hundreds of the slain Talligewi, whom I shall hereafter, with Colonel Gibson, call Alligewi. Of these intrenchments Mr. Abraham Steiner, who was with me at the time when I saw them, gave a very accurate description, which was published at Philadelphia in 1789 or 1790, in some periodical work the name of which I can not at present remember.

When the Lenape arrived on the banks of the Mississippi they sent a message to the Alligewi to request permission to settle themselves in their neighborhood. This was refused them, but they obtained leave to pass through the country and seek a settlement farther to the eastward. They accordingly began to cross the Namaesi—Sipu, when the Alligewi, seeing that their numbers were so very great, and in fact they consisted of many thousands, made a furious attack upon those who had crossed, threatening them all with destruction, if they dared to persist in coming over to their side of the river. Fired at the treachery of these people, and the great loss of men they had sustained, and besides, not being prepared for a conflict, the Lenapi consulted on what was to be done; whether to retreat in the best manner they could, or to try their strength, and let the enemy see that they were not cowards, but men, and too high—minded to suffer themselves to be driven off before they had made a trial of their strength and were convinced that the enemy was too powerful for them. The Mengwe, who had hitherto been satisfied with being spectators from a distance, offered to join them, on condition that, after conquering the country, they should be entitled to share it with them; their proposal was accepted, and the resolution was taken by the two nations, to conquer or die.

Having thus united their forces the Lenape and Mengwe declared war against the Alligewi, and great battles were fought in which many warriors fell on both sides. The enemy fortified their large towns and erected fortifications, especially on large rivers and near lakes, where they were successfully attacked and sometimes stormed by the allies. An engagement took place in which hundreds fell, who were afterwards [pg 45]buried in holes or laid together in heaps and covered over with earth. No quarter was given, so that the Alligewi at last, finding that their destruction was inevitable if they persisted in their obstinacy, abandoned the country to the conquerors and fled down the Mississippi River, from whence they never returned.

The war which was carried on with this nation lasted many years, during which the Lenape lost a great number of their warriors, while the Mengwe would always hang back in the rear leaving them to face the enemy. In the end the conquerors divided the country between themselves. The Mengwe made choice of the lands in the vicinity of the great lakes and on their tributary streams, and the Lenape took possession of the country to the south. For a long period of time, some say many hundred years, the two nations resided peacefully in this country and increased very fast. Some of their most enterprising huntsmen and warriors crossed the great swamps, and falling on streams running to the eastward followed them down to the great bay river (meaning the Susquehanna, which they call the great bay river from where the west branch falls into the main stream), thence into the bay itself, which we call Chesapeake. As they pursued their travels, partly by land and partly by water, sometimes near and at other times on the great salt—water lake, as they call the sea, they discovered the great river which we call the Delaware.

This quotation, although not the entire tradition as given by Heckewelder, will suffice for the present purpose.

The traces of the name of these mound—builders, which are still preserved in the name “Allegheny,” applied to a river and the mountains of Pennsylvania, and the fact that the Delawares down to the time Heckewelder composed his work called the Allegheny River “Allegewi Sipu,” or river of the Allegewi, furnish evidence that there is at least a vein of truth in this tradition. If it has any foundation in fact there must have been a people to whom the name “Tallegwi” [Footnote: There appears to be no real foundation for the name Allegewi, this form being a mere supposition of Colonel Gibson, suggested by the name the Lenape applied to the Allegheny River and Mountains.] was applied, for on this the whole tradition hangs. Who were they? In what tribe and by what name shall we identify them? That they were mound—builders is positively asserted, and the writer explains what he means by referring to certain mounds and inclosures, which are well known at the present day, which he says the Indians informed him were built by this people.

It is all—important to bear in mind the fact that when this tradition was first made known, and the mounds mentioned were attributed to this people, these ancient works were almost unknown to the investigating minds of the country. This forbids the supposition that the tradition was warped or shaped to fit a theory in regard to the origin of these antiquities.

Following the tradition it is fair to conclude, notwithstanding the fact that Heckewelder interpreted “Namaesi Sipu” by Mississippi, that the principal seats of this tribe or nation were in the region of the Ohio and the western slope of the Allegheny Mountains, and hence it is not wholly a gratuitous supposition to believe they were the authors of some of the principal ancient works of eastern Ohio (including those of the Scioto Valley) and the western part of West Virginia. Moreover, there is the statement by Haywood, already referred to, that the Cherokees had a tradition that in former times they dwelt on the Ohio and built mounds.

These data, though slender, when combined with the apparent similarity between the name Tallegwi and Cherokee or Chellakee, and the character of the works and traditions of the latter, furnish some ground for assuming that the two were one and the same people. But this assumption necessitates the further inference that the pressure which drove them southward is to be attributed to some other people than the Iroquois as known to history, as this movement must have taken place previous to the time the latter attained their ascendancy. It is probable that Mr. Hale is correct in deciding that the “Namaesi Sipu” of the tradition was not the Mississippi. [Footnote: Am. Antiquarian, vol. 5, 1883, p. 117.] His suggestion that it was that portion of the great river of the North (the St. Lawrence) which connects Lake Huron with Lake Erie, seems also to be more in conformity with the tradition and other data than any other which has been offered. If this supposition is accepted it would lead to the inference that the Talamatau, the people who joined the Delawares in their war on the Tallegwi, were Hurons or Huron—Iroquois previous to separation. That the reader may have the benefit of Mr. Hale’s views on this question, the following quotation from the article mentioned is given:

The country from which the Lenape migrated was Shinaki, the “land of fir trees,” not in the West but in the far North, evidently the woody region north of Lake Superior. The people who joined them in the war against the Allighewi (or Tallegwi, as they are called in this record), were the Talamatan, a name meaning “not of themselves,” whom Mr. Squier identities with the Hurons, and no doubt correctly, if we understand by this name the Huron—Iroquois people, as they existed before their separation. The river which they crossed was the Messusipu, the Great River, beyond which the Tallegwi were found “possessing the East.” That this river was not our Mississippi is evident from the fact that the works of the mound—builders extended far to the westward of the latter river, and would have been encountered by the invading nations, if they had approached it from the west, long before they arrived at its banks. The “Great River” was apparently the upper St. Lawrence, and most probably that portion of it which flows from Lake Huron to Lake Erie, and which is commonly known as the Detroit River. Near this river, according to Heckewelder, at a point west of Lake St. Clair, and also at another place just south of Lake Erie, some desperate conflicts took place. Hundreds of the slain Tallegwi, as he was told, were buried under mounds in that vicinity. This precisely accords with Cusick’s statement that the people of the great southern empire had “almost penetrated to Lake Erie” at the time when the war began. Of course in coming to the Detroit River from the region north of Lake Superior, the Algonquins would be advancing from the west to the east. It is quite conceivable that, after many generations and many wanderings, they may themselves have forgotten which was the true Messusipu, or Great River, of their traditionary tales.

The passage already quoted from Cusick’s narrative informs us that the contest lasted “perhaps one hundred years.” In close agreement with this statement the Delaware record makes it endure during the terms of four head—chiefs, who in succession presided in the Lenape councils. From what we know historically of Indian customs the average terms of such chiefs may be computed at about twenty—five years. The following extract from the record [Footnote: The Bark Record of the Leni Lenape.] gives their names and probably the fullest account of the conflict which we shall ever possess:

“Some went to the East, and the Tallegwi killed a portion.

“Then all of one mind exclaimed, War! War!

“The Talamatan (not—of—themselves) and the Nitilowan [allied north—people] go united (to the war).

“Kinnepehend (Sharp—Looking) was the leader, and they went over the river. And they took all that was there and despoiled and slew the Tallegwi.

“Pimokhasuwi (Stirring—about) was next chief, and then the Tallegwi were much too strong.

“Tenchekensit (Open—path) followed, and many towns were given up to him.

“Paganchihiella was chief, and the Tallegwi all went southward.

“South of the Lakes they (the Lenape) settled their council—fire, and north of the Lakes were their friends the Talamatan (Hurons!).”

There can he no reasonable doubt that the Alleghewi or Tallegwi, who have given their name to the Allegheny River and Mountains, were the mound—builders.

This supposition brings the pressing hordes to the northwest of the Ohio mound—builders, which is the direction, Colonel Force concludes, from the geographical position of the defensive works, they must have come.

The number of defensive works erected during the contest shows it must have been long and obstinate, and that the nation which could thus resist the attack of the northern hordes must have been strong in numbers and fertile in resources. But resistance proved in vain; they were compelled at last, according to the tradition, to leave the graves of their ancestors and flee southward in search of a place of safety.

Here the Delaware tradition drops them, but the echo comes up from the hills of East Tennessee and North Carolina in the form of the Cherokee tradition already mentioned, telling us where they found a resting place, and the mound testimony furnishes the intermediate link.

If they stopped for a time on New River and the head of the Holston, as Haywood conjectures, [Footnote: Nat. and Aborig. Hist. Tenn., p. 223.—See Thomas, “Cherokees probably mound—builders,” Magazine Am. Hist., May. 1884, p. 398.] their line of retreat was in all likelihood up the valley of the Great Kanawha. This supposition agrees also with the fact that no traces of them are found in the ancient works of Kentucky or middle Tennessee. In truth, the works along the Ohio River from Portsmouth to Cincinnati and throughout northern Kentucky pertain to entirely different types from those of Ohio, most of them to a type found in no other section.

On the contrary, it happens precisely in accordance with the theory advanced and the Cherokeee traditions, that we find in the Kanawha Valley, near the city of Charleston, a very extensive group of ancient works stretching along the banks of the stream for more than two miles, consisting of quite large as well as small mounds, of circular and rectangular inclosures, etc. A careful survey of this group has been made and a number of the tumuli, including the larger ones, have been explored by the representatives of the Bureau.

The result of these explorations has been to bring to light some very important data bearing upon the question now under consideration. In fact we find here what seems to be beyond all reasonable doubt the connecting link between the typical works of Ohio and those of East Tennessee and North Carolina ascribed to the Cherokees.

The little stone vaults in the shape of bee—hives noticed and figured in the articles in Science and the American Naturalist, before referred to, discovered by the Bureau assistants in Caldwell County, N. C., and Sullivan County, Tenn., are so unusual as to justify the belief that they are the work of a particular tribe, or at least pertain to an ethnic type. Yet under one of the large mounds at Charleston, on the bottom of a pit dug in the original soil, a number of vaults of precisely the same form were found, placed, like those of the Sullivan County mound, in a circle. But, though covering human remains moldered back to dust, they were of hardened clay instead of stone. Nevertheless, the similarity in form, size, use, and conditions under which they were found is remarkable, and, as they have been found only at the points mentioned, the probability is suggested that the builders in the two sections were related.

There is another link equally strong. In a number of the larger mounds on the sites of the “over—hill towns,” in Blount and Loudon Counties, Tenn., saucer—shaped beds of burnt clay, one above another, alternating with layers of coals and ashes, were found. Similar beds were also found in the mounds at Charleston. These are also unusual, and, so far as I am aware, have been found only in these two localities. Possibly they are outgrowths of the clay altars of the Ohio mounds, and, if so, reveal to us the probable use of these strange structures. They were places where captives were tortured and burned, the most common sacrifices the Indians were accustomed to make. Be this supposition worthy of consideration or not, it is a fact worthy of notice in this connection that in one of the large mounds in this Kanawha group one of the so—called “clay altars” was found at the bottom of precisely the same pattern as those found by Squier and Davis in the mounds of Ohio.

In these mounds were also found wooden vaults, constructed In exactly the same manner as that in the lower part of the Grave Creek mound; also others of the pattern of those found in the Ohio mounds, in which bark wrappings were used to enshroud the dead. Hammered copper bracelets, hematite celts and hemispheres, and mica plates, so characteristic of the Ohio tumuli, were also discovered here; and, as in East Tennessee and Ohio, we find at the bottom of mounds in this locality the post—holes or little pits which have recently excited considerable attention. We see another connecting link in the circular and rectangular inclosures, not combined as in Ohio, but analogous, and, considering the restricted area of the narrow valley, bearing as strong resemblance as might be expected if the builders of the two localities were one people.

Talligewi Citys, Fortifications, Mounds and Earthworks.

It would be unreasonable to assume that all these similarities in customs, most of which are abnormal, are but accidental coincidences due to necessity and environment. On the contrary it will probably be conceded that the testimony adduced and the reasons presented justify the conclusion that the ancestors of the Cherokees were the builders of some at least of the typical works of Ohio; or, at any rate, that they entitle this conclusion to favorable consideration. Few, if any, will longer doubt that the Cherokees were mound builders in their historic seats in North Carolina and Tennessee. Starting with this basis, and taking the mound testimony, of which not even a tithe has been presented, the tradition of the Cherokees, the statement of Haywood, the Delaware tradition as given by Heckewelder, the Bark Record as published by Brinton and interpreted by Hale, and the close resemblance between the names Tallegwi and Chellakee, it would seem that there can remain little doubt that the two peoples were identical.

It is at least apparent that the ancient works of the Kanawha Valley and other parts of West Virginia are more nearly related to those of Ohio than to those of any other region, and hence they may justly be attributed to the same or cognate tribes. The general movement, therefore, must have been southward as indicated, and the exit of the Ohio mound—builders was, in all probability, up the Kanawha Valley on the same line that the Cherokees appear to have followed in reaching their historical locality. It is a singular fact and worthy of being mentioned here, that among the Cherokee names signed to the treaty made between the United States and this tribe at Tellico, in 1798, are the following: [Footnote: Treaties between the United States of America and the several Indian tribes (1837), p. 182.] Tallotuskee, Chellokee, Yonaheguah, Keenakunnah, and Teekakatoheeunah, which strongly suggest relationship to names found in the Allegheny region, although the latter come to us through the Delaware tongue.

If the hypothesis here advanced be correct, it is apparent that the Cherokees entered the immediate valley of the Mississippi from the northwest, striking it in the region of Iowa. This supposition is strengthened not only by the similarity in the forms of the pipes found in the two sections, but also in the structure and contents of many of the mounds found along the Mississippi in the region of western Illinois. So striking is this that it has been remarked by explorers whose opinions could not have been biased by this theory.

Mr. William McAdams, in an address to the American Association for the Advancement of Science, remarks: “Mounds, such as are here described, in the American Bottom and low—lands of Illinois are seldom, if ever, found on the bluffs. On the rich bottom lands of the Illinois River, within 50 miles of its mouth, I have seen great numbers of them and examined several. The people who built them are probably connected with the Ohio mound—builders, although in this vicinity they seem not to have made many earthen embankments, or walls inclosing areas of land, as is common in Ohio. Their manner of burial was similar to the Ohio mound— builders, however, and in this particular they had customs similar to the mound—builders of Europe.” [Footnote: Proc. Am. Assoc. Adv. Sci., 29th (Boston) meeting, 1880 (1881), p. 715.] One which he opened in Calhoun County, presented the regular form of the Ohio “altar.”

A mound in Franklin County, Ind., described and figured by Dr. G. W. Homsher, [Footnote: Smithsonian Report for 1882 (1884), p. 722.] presents some features strongly resembling those of the North Carolina mounds.

The works of Cuyahoga County and other sections of northern Ohio bordering the lake, and consisting chiefly of inclosures and defensive walls, are of the same type as those of New York, and may be attributed to people of the Iroquoian stock. Possibly they may be the works of the Eries who, we are informed, built inclosures. If such conclusion be accepted it serves to strengthen the opinion that this lost tribe was related to the Iroquois. The works of this type are also found along the eastern portion of Michigan as far north as Ogemaw County.

The box shaped stone graves of the State are due to the Delawares and Shawnees, chiefly the former, who continued to bury in sepulchers of this type after their return from the East. Those in Ashland and some other counties, as is well known, mark the location of villages of this tribe. Those along the Ohio, which are chiefly sporadic, are probably Shawnee burial places, and older than those of the Delawares. The bands of the Shawnees which settled in the Scioto Valley appear to have abandoned this method of burial.

There are certain mounds consisting entirely or in part of stone, and also stone graves or vaults of a peculiar type, found in the extreme southern portions of the State and in the northern part of Kentucky, which can not be connected with any other works, and probably owe their origin to a people who either became extinct or merged into some other tribe so far back that no tradition of them now remains.

Recently a resurvey of the remaining circular, square, and octagonal works of Ohio has been made by the Bureau agents. The result will be given in a future bulletin. Read More Here:

Mound-Builders, Mormons, and Joseph Smith

The Mound Builders of North America are connected with the Hopewell Culture of 600 BC to 400 AD which is connected to the Nephite civilization. WOW!

“This linking of the biblical world with the treasure-seeking environment of nineteenth-century New York through the indisputable presence of Native Americans likely impacted how the origins of the Book of Mormon were viewed upon its publication. Not surprisingly, local residents of Palmyra confused Joseph Smith’s claims about the ancient inhabitants described in the Book of Mormon with his earlier money digging experiences. Dahl even categorized the Book of Mormon as Mound Builder literature.

There was little difference between ancient angels, like the one that showed Joseph the plates, and ancient treasure guardians in the minds of some of the local residents when they reflected back upon what Joseph experienced in the early 1820s. This was in spite of the fact that interest in buried Native American artifacts was a deep-seated American interest closely associated with Christianity. Interest in Native American ruins or treasures buried in the New York landscape was not just a money digger’s preoccupation.

Curtis Dahl explained, “The Romantic love of the distant past, the desire to provide the new country with an antique and glorious history, and the controversy over American natural history between nationalistic Americans and the followers of the French naturalist Buffon prompted a number of archaeological books and articles on these mysterious ancient inhabitants of America [from 1800–1840],”

Curtis Dahl, “Mound-Builders, Mormons, and William Cullen Bryant,” New England Quarterly 34 (June 1961): 178. The idea of ancient mound builders was fairly well known and even supported and perpetuated by local Palmyra newspapers.

For examples, see “Indian Antiquities,” Palmyra Register, 21 January 1818, and Palmyra Herald, 19 February 1823. Dahl, “Mound-Builders,” 178–90. See also William A. Ritchie, The Archaeology of New York State (Garden City, NY: Natural History Press, 1965).

North America Inhabited by a White People before the Ancients (Jaredites)

By D. C. Miller. Batavia, N. Y., October 18, 1822. Vol. 11, No. 553.

AMERICAN ANTIQUITIES.

To the editors of the Louisiana Republican.

Gentlemen: —

In the course of my observation & travels through several parts of the United States, I have kept minutes of the most remarkable events which have occurred under my own observation, extracts from which I design, occasionally, to submit to you, and if you think them worthy of insertion in your useful paper, you are at liberty to use them accordingly.

All accounts extant, relative to the size of the ancient settlers of our country, agree that this race of beings must have been larger than the present; but none that I have seen give any evidence of this fact. From my own observation, I have evidence at least of one person of gigantic stature.

In the year 1810, I opened, with several other persons who accompanied me for the purpose, one of the flat mounds common in the western country. It was built of regular layers of flat stones, and covered lightly with earth. This was 4 miles west of the town of Worthington, in Ohio, and within a few rods of the banks of the river Scioto. — In this mound we found the skeletons of a number of bodies, some of a very large size, they were deposited directly due east and west, the heads to the west; precisely as is the practice in Christian burials.

After several hours fatigue in opening & examining this mound, we retired to a house of a Mr. Miller, about 200 yards from the spot, who informed us that he had taken a skeleton from the mound adjoining the one we had examined, which was supposed to be, when living, a man of at least 7 feet 4 inches. He stated that such was the opinion of all who had seen the bones in his possession — that the bone of the leg, which had lost a little at each end, was then longer than the bone of the tallest man in the settlement, measuring from the heel to the cap of the knee.

Mr. Miller stated that he had also in his possession, the jaw bone of this skeleton, which he said, would cover loosely the face of any of his neighbors; and that, when he found the skeleton, he picked from one of the joints of the neck bone, (which was also much larger than any he had seen before,) a stone arrow point; from which circumstances, it was thought his death had been occasioned. I made many inquiries of Mr. Miller, who seemed to be a very intelligent man. He informed me that he had been living at his residence on the Scioto, for many years; — that when he first settled there, he was told by all the old Indians that these mounds existed at a period beyond the recollection of the oldest of them, and that the tribe of Indians before them could give no account of the mounds, other than that they were burying places before they inhabited the country.

From these circumstances, together with some others, which have come under my observation, I have been of opinion, that the bones frequently found in these mounds, must have been the skeletons of a race of beings inhabiting the country, of whom the Indians had no knowledge. The most remarkable circumstance stated by Mr. Miller was, that when ploughing his field, he traced plainly the remains of an ancient building in the form of a house, as there was a manifest difference in the appearance of the earth; and pointing at the same time to the hearth stone in his fire-place, he observed “the hearth-stone which you see there, I took myself from the place where I suppose the fire-place was in the ancient building of which I speak.” The Indians, he added, gave him the same account of the appearance of this old building as they had of the mounds; that it existed before their time. During the war, and while on my way to Detroit, I intended calling on Mr. Miller, for more particular information, but upon my arrival at Worthington, I learned that he was dead.

Every information tending to prove the existence of a vast ancient population of any part of our country, ought to be preserved — but few persons can or will afford to spend time and money to the attainment of such an object. I have occasionally noted what had passed under my observation since the year 1807 in the western country; and, as I find leisure, will transmit them to you to be filed away through the medium of your paper, till better proof can be obtained of the existence of a vast ancient population of our country.