Translation Methods and Understanding with Martin Harris, Samuel Mitchell, Charles Anthon, and Jean-François Champollion.

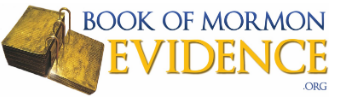

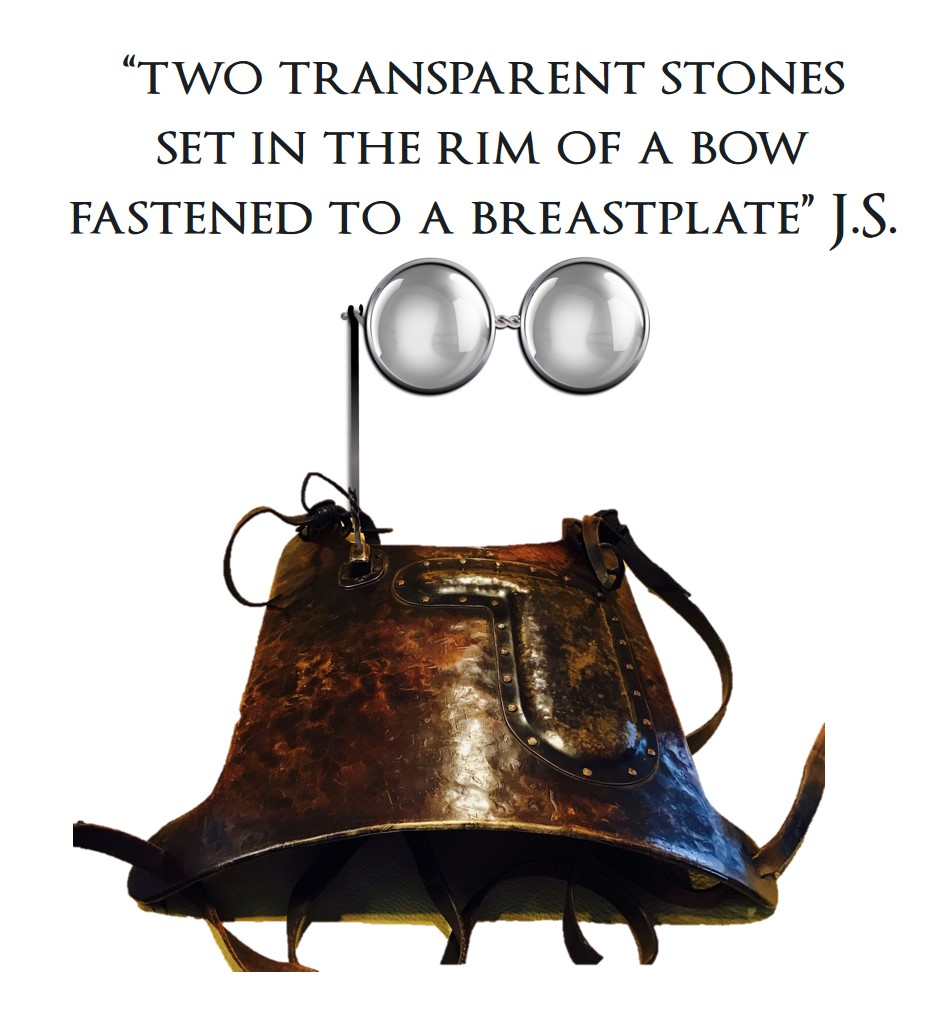

Let us begin looking at the deep understanding of some renowned men. about the possibilities in regard to the translation of ancient records including the Book of Mormon. All the men we will speak about below either contributed, assisted, resisted, new about, or taught about, some methods of translation of ancient records. Some supported Joseph Smith, some did not, and some contributed to understanding methods of translation that make Joseph’s inspired story of translation even more believable than it already is. Many Church Historians and Professors continue to speak about (SITH) Stone in the Hat and (SSS) Silly Seer Stone. I continue to believe the Prophet Joseph and Scripture, some included below which say, “And now he translated them by the means of those two stones which were fastened into the two rims of a bow…” Mosiah 28:13. Also read “And behold, these two stones [different than the previous 16 stones]will I give unto thee, and ye shall seal them up also with the things which ye shall write. For behold, the language which ye shall write I have confounded; wherefore I will cause in my own due time that these stones [2 stones] shall magnify to the eyes of men these things which ye shall write.” Ether 3:23:24 (Parenthesis Added)

Many Church Historians and Professors continue to speak about (SITH) Stone in the Hat and (SSS) Silly Seer Stone. I continue to believe the Prophet Joseph and Scripture, some included below which say, “And now he translated them by the means of those two stones which were fastened into the two rims of a bow…” Mosiah 28:13. Also read “And behold, these two stones [different than the previous 16 stones]will I give unto thee, and ye shall seal them up also with the things which ye shall write. For behold, the language which ye shall write I have confounded; wherefore I will cause in my own due time that these stones [2 stones] shall magnify to the eyes of men these things which ye shall write.” Ether 3:23:24 (Parenthesis Added)

Joseph Smith himself said, “With the records was found a curious instrument, which the ancients called “Urim and Thummim,” which consisted of two transparent stones set in the rim of a bow fastened to a breast plate. Through the medium of the Urim and Thummim I translated the record by the gift and power of God.” (History of the Church, 4:537 Wentworth Letter).

This article will now add a few names of renowned reputation who speak about the translation either directly or indirectly and add their witnesses of method, means and possibilities of how Joseph describes the translation as, “by the Gift and power of God.”

Martin Harris Brief

“Few episodes in early Mormon history are as fascinating—and problematic—as the February 1828 visit of Martin Harris to Professor Charles Anthon of Columbia College in New York City…

Harris sought out Mitchill first, who then wrote a letter referring him to Anthon. Harris later recounted that Anthon “stated that the translation was correct, more so than any he had before seen translated from the Egyptian…

He [Harris] carried the engravings from the plates to New York— shewed them to Professor Anthon who said that he did not know what language they were—Told him to carry them to Dr. Mitchell. Doctor Mitchell examined them and compared them with other hieroglyphs—thought them very curious—said they were the characters of a nation now extinct which he named.” Richard E. Bennett

Samuel Mitchill Brief

“Dr. Samuel Mitchill new the origins of the Native Americans of North America. He seems to have known their civilization ended right where Joseph Smith said it did. Mitchell said, “the great last battles between these warring peoples had occurred in upstate New York, a few miles southeast of Rochester…

Mitchill had been studying the origins of the American Indian people for several years and had painstakingly developed his own “two races” theory of ancient America.[29] His interest in the history of the ancient American Indians was therefore at a peak when Harris showed him the transcripts…

Mitchill also said, “they were the characters of a nation now extinct which he named, as the the “Iroquois” Indians of “Tartar descent…

Mitchell was a student of many American Indian languages, hieroglyphs, and native dialects. He also knew of Champollion’s great work…

Mitchill wrote to NY Governor Clinton in 1816, ‘The surviving race in these terrible conflicts between the different nations of the ancient natives residents of North America, is evidently that of the Tartars.'” Archaeologia Americana, 326 Brief Quotes of Richard E. Bennett

Mitchill Quote

“The battles are described as often having culminated in the destruction of previous, superior Native cultures which had taken final refuge in forts at the tops of hills, including the general region of the hill known to Mormons as Cumorah. In the town of Camillus, in the same county of Onondaga . . . there are two ancient forts . . . One is on a very high hill, and its area covers about three acres. . . . The ditch was deep and the eastern wall ten feet high. In the centre was a large lime stone of an irregular shape.” (See Map of the Ancient Nephite Battlegrounds Below)

A Memoir on the Antiquities of the Western Parts of the State of New-York, Addressed to the Honourable Samuel L. Mitchill, a Vice-President of the Literary and Philosophical Society of New York . . . by Dewitt Clinton . . . Read Before the Society November 13th, 1817 De Witt Clinton (1769-1828)

Professor Charles Anthon Brief

“Anthon began his study of Greek and Latin at Columbia when only fourteen years of age…

Professor Charles Anthon, “was probably aware of emerging research interests in Egyptian hieroglyphics and of the recent decodings of the ancient Egyptian writings on the Rosetta Stone by the magnificent French linguist Jean-François Champollion. Richard E. Bennett

Professor Charles Anthon, “was probably aware of emerging research interests in Egyptian hieroglyphics and of the recent decodings of the ancient Egyptian writings on the Rosetta Stone by the magnificent French linguist Jean-François Champollion. Richard E. Bennett

French linguist Jean-François Champollion Brief

“The Translation by Joseph Smith has been compared to “the superlative translator of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic writing, the brilliant French linguist Jean-François Champollion. Just five years before, Champollion had finally decoded the mysterious hieroglyphs of the famed Rosetta Stone found near Alexandria by Napoleon’s army in 1799…

Among the better-known published works on Egyptian hieroglyphics available in 1828 was Jean-Francois Champollion’s famous Lettre a M. Dacier (1822) and his follow-up work, Precis du Systeme Hieroglyphique (1824). The latter two works of Champollion not only gave facsimiles of hieroglyphs but code-breaking translations…

Joseph Smith was not a decoder or a pure translator in the Champollion sense of the word but a transmitter/translator and writer who, with the aid of the interpreters, transposed what “he saw into exquisite English prose and poetry.” Richard E. Bennett

Martin Harris’s 1828 Visit to Luther Bradish, Charles Anthon, and Samuel Mitchill.

“Few episodes in early Mormon history are as fascinating—and problematic—as the February 1828 visit of Martin Harris to Professor Charles Anthon of Columbia College in New York City. Scholars from both within and without the Church—those seeking corroboration for the translation of the Book of Mormon as well as those trying to debunk the authenticity of the whole story—continue to grapple with the details of this event and its implications…

While there are details we do not fully know, it is clear that Harris returned from the East confirmed in his desire to assist in the translation and printing of the Book of Mormon, although perhaps for additional reasons than long supposed.[1]

The outlines of this story are well known in Mormon history. Working with the gold plates, Joseph Smith began the work of early translating in late 1827 from the “Reformed Egyptian” language found on Mormon’s abridgment of the large plates of Nephi. Early on, he transcribed some of the characters from the plates as a sort of alphabet or reference guide.[2] His primary scribe was Martin Harris, a respected Palmyra farmer, an early and keen supporter of Smith’s work who later became one of the Three Witnesses to the Book of Mormon. For a variety of reasons, Harris begged leave to take a transcription of the characters Smith had come across in his translation attempts to New York City, as historian B. H. Roberts writes, “to submit them to men of learning for their inspection.”[3] Roberts says Harris submitted “two papers containing different transcripts, to Professors Anthon and Mitch[i]ll, of New York, one that was translated and one not translated.”[4] According to Anthon’s own accounts, Harris sought out Mitchill first, who then wrote a letter referring him to Anthon.[5] Harris later recounted that Anthon “stated that the translation was correct, more so than any he had before seen translated from the Egyptian,” and after viewing the characters “said that they were Egyptian, Chaldaic, Assyriac, and Arabic, and he said that they were true characters and that the translation of such of them that had been translated was correct.” He even wrote a note “certifying to the people of Palmyra that they were true characters.” However, upon hearing Harris say in answer to his question that an angel of God had revealed such things and that part of the plates were sealed, Anthon promptly tore up his certificate. Denying the possibility of angels and of all such heavenly manifestations, he asked Harris to bring him the plates for him to translate. When Harris replied he could not do so and that parts of the plates were sealed, the man from Columbia brusquely responded, “I cannot read a sealed book.” Harris then returned to Mitchill, “who sanctioned what Professor Anthon had said respecting both the characters and the translation” (Joseph Smith—History 1:65)…

However, before offering his learned opinion on the written characters which Harris brought with him, Mitchill kindly referred him to his colleague, the young and upcoming scholar of linguistics, the thirty-one-year-old Professor Charles Anthon (1797–1867), AB, LLD. Born in New York City, Anthon began his study of Greek and Latin at Columbia when only fourteen years of age. At age twenty-three, he took up a position of professor of languages at Columbia. His famous edition of Lempriere’s Classical Dictionary, first published in 1825, had already marked Anthon as a rising classical scholar. However, in 1828 he was but an adjunct professor of Greek and Latin, more an accomplished grammarian than a prestigious scholar. His first love was the classics, especially the works of Homer and Herodotus. While he knew Greek, Latin, German, and French superbly well, there is little indication he knew much about Egyptian, Hebrew, or any other Middle Eastern language. Because of his love of languages, he was probably aware of emerging research interests in Egyptian hieroglyphics and of the recent decodings of the ancient Egyptian writings on the Rosetta Stone by the magnificent French linguist Jean-François Champollion [27] And, while it is reasonable to conclude that he may have been interested in ancient Near Eastern languages, Anthon was by no means a scholar of such. By force of his own brusque personality, he claimed to know more in this area than he really did.

When Anthon showed Harris the door, Mitchill welcomed him back and sanctioned what Harris showed him for at least two reasons. Like Anthon, Mitchill was a linguist having studied the Oriental languages, the classical languages of Greek and Latin, and was a student of many American Indian languages, hieroglyphs, and native dialects. He also knew of Champollion’s great work.[28]

But, unlike his junior colleague, Mitchill had been studying the origins of the American Indian people for several years and had painstakingly developed his own “two races” theory of ancient America.[29] His interest in the history of the ancient American Indians was therefore at a peak when Harris showed him the transcripts.[30]

Professor Mitchill had, in fact, arrived at the conclusion that “three races of Malays, Tartars, and Scandinavians, contribute to make up the American population.” [31] He believed that the Tartars (as he called the originating stock) were primarily from northeastern Russia and China.[32] He also had concluded that another great race of people had once coinhabited ancient America— a “more delicate race”—which he believed originated in the Polynesian Islands of the South Pacific. These people he called the Australasians or Malays. They were, however, eventually overtaken and exterminated by the more savage, warlike Tartars or Eastern Asiatics to the North—the ancestors of many of the North American Indians—and had long ago become extinct. Mitchill had come to the conclusion that they have probably been overcome by the more warlike and ferocious hordes that entered our hemisphere from the northeast of Asia. These Tartars of the higher latitudes have issued from the great hive of nations, and desolated, in the course of their migrations, the southern tribes of America, as they have done to those of Asia and Europe. The greater part of the North American natives are of the Tartar stock, the descendants of the hardy warriors who destroyed the weaker Malays that preceded them.[33]

Mitchill maintained that the “Iroquois” Indians were of “Tartar descent, who expelled or destroyed the former possessors of the fertile tracts reaching from Lake Ontario south westwardly to the River Ohio.”[34] He went on to argue that the great last battles between these warring peoples had occurred in upstate New York, a few miles southeast of Rochester and not far from Palmyra, Harris’ home.

It was probably for these and perhaps other reasons that Mitchill showed deep interest in the transcript of the characters Harris showed him. Whether or not he wrote anything to substantiate the veracity of the characters is yet unknown; however, we now know what the two men said to each other. According to the 1831 journal of New York newspaper reporter, Gordon Bennett, arguably the earliest account of Harris’ visit to New York,

He [Harris] carried the engravings from the plates to New York— shewed them to Professor Anthon who said that he did not know what language they were—Told him to carry them to Dr. Mitchell. Doctor Mitchell examined them and compared them with other hieroglyphs—thought them very curious—said they were the characters of a nation now extinct which he named.[35]

Notes from Martin Harris’s 1828 Visit to Luther Bradish, Charles Anthon, and Samuel Mitchill.

[27] Among the better-known published works on Egyptian hieroglyphics available in 1828 were Jean-Pierre Rigord’s longstanding Memoire de Trevoux, first published in 1704, Georg Zoega’s Du Origine et Usu Obeliscorum (1797), Les Description d’Egypte, (1809), Thomas Young’s Museum Criticum vi (1815), and Jean-Francois Champollion’s famous Lettre a M. Dacier (1822) and his follow-up work, Precis du Systeme Hieroglyphique (1824). The latter two works of Champollion not only gave facsimiles of hieroglyphs but code-breaking translations. How many of these works Anthon or Mitchill had in their possession or were aware of is impossible to determine. For a good study on this topic, see Maurice Pope, The Story of Decipherment—From Egyptian Hieroglyphs to Maya Script, rev. ed. (London: Thomas and Hudson, 1999), chapters 2 and 3.

[28] Francis, “Reminiscences of Samuel Latham Mitchill,” 16–18. At one time he gave a “profound exegetical disquisition upon Kennicott’s Hebrew Bible in disproof of the interpretations of Gershom Seixas, the great Jewish rabbi of the age.” Beverly Smith, The Lantern, College Papers.

[29] Mitchill, “Discourse on Thomas Jefferson,” 15.

[30] Samuel L. Mitchill, A Lecture on Some Parts of the Natural History of New Jersey. Delivered Before the Newark Mechanic Association . . . 3 June 1828 (New York: Elliott and Palmer, 1828).

[31] Letter of Samuel L. Mitchill of New York to Samuel M. Burnside, Esq, Corresponding Secretary of the American Antiquarian Society, January 13, 1817, as published in Archaeologia Americana: Transactions and Collections of the American Antiquarian Society (1885; repr., Worchester, MA: Johnson Reprint, 1971), 1:314–15.

[32] E. Howitt, Selections from Letters Written During a Tour of the United States, in the Summer and Autumn of 1819 Illustrative of the Character of the Native Indians, and Their Descent from the Lost Ten Tribes of Israel (Nottingham, England: J. Dunn, 1819).

[33] Archaeologia Americana, 324–25. Mitchill went on to write Clinton in 1816 that “the northern tribes were probably more hardy, ferocious, and warlike than those of the south” and that “the hordes dwelling in the higher latitudes have overpowered the more civilized, though feebler inhabitants of the countries situated towards the equator. . . . The surviving race in these terrible conflicts between the different nations of the ancient natives residents of North America, is evidently that of the Tartars.” Archaeologia Americana, 326.

[34] Samuel L. Mitchill to John W. Francis, September 13, 1816, Samuel L. Mitchill Collection, Rare Books Dept., Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard University Library, Boston.

[35] From an original twenty-nine-page holograph journal of James Gordon Bennett, June 12–August 18, 1831. Bennett’s holograph journal tells of his journey through upstate New York, part of the time in company with Martin Van Buren, Benjamin F. Butler, and Nathaniel S. Benton. Special Collections, New York Public Library, New York City.

Richard E. Bennett, “Martin Harris’s 1828 Visit to Luther Bradish, Charles Anthon, and Samuel Mitchill,” in The Coming Forth of the Book of Mormon: A Marvelous Work and a Wonder, edited by Dennis L. Largey, Andrew H. Hedges, John Hilton III, and Kerry Hull (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 103–15.

Joseph Smith and the First Principles of the Gospel

By Richard E. Bennett Recently published in Joseph Smith, the Prophet and Seer (Provo, UT, and Salt Lake City: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, and Deseret Book, 2010).

French Linguist Jean-François Champollion

“The specifics of translation remain a mystery, but it may be instructive to compare the work of Joseph Smith to that of his magnificent contemporary, the superlative translator of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic writing, the brilliant French linguist Jean-François Champollion. Just five years before, Champollion had finally decoded the mysterious hieroglyphs of the famed Rosetta Stone found near Alexandria by Napoleon’s army in 1799.

Joseph Smith, Oliver Cowdery, and the Process of Translation, 1829

We now come to our third and final episode, that period of translation in which Joseph Smith and his new scribe, Oliver Cowdery, completed the Book of Mormon as we now know it. Virtually the same age as Joseph, Oliver (1806–50) was also from Vermont, had been a store clerk and taught in country schools. While boarding with Joseph Smith’s parents, he learned of the ancient record and the lost 116 pages. What piqued his interest in the work was the fact that he had “inquired of the Lord” on the matter. As recorded in the Doctrine and Covenants, “as often as thou hast inquired thou hast received instruction of my Spirit. If it had not been so, thou wouldst not have come to the place where thou art at this time” (D&C 6:14). Joseph Smith said, “The Lord appeared unto . . . Oliver Cowdery and shewed unto him the plates in a vision and . . . what the Lord was about to do through me, his unworthy servant. Therefore he was desirous to come and write for me to translate.”[12]

The two men met each other for the first time on April 5, 1829, arranged some temporal business together the following day, and began the work of translation on April 7. Partners in the translating process, the great difference between the two men was in their spiritual preparation and academic approach to the task at hand. A teacher by profession who knew well how to read and write and do numbers far better than his partner, Oliver was nevertheless Joseph’s pupil in the first principles.

The profound intellectual difficulties Joseph Smith faced in translating an ancient unknown language even with the aid of the Urim and Thummim are hinted at in Oliver’s parallel failed experience as a translator and afford us yet another view of how repentance was once more taught during the translation process. It is noteworthy that the second elder of the Restoration began his mission by seeking the gift to translate. “Ask that you may know the mysteries of God, and that you may translate and receive knowledge from all those ancient records which have been hid up, that are sacred; and according to your faith shall it be done unto you” (D&C 8:11). However, as Elder Dallin H. Oaks has indicated, Oliver soon “failed in his efforts to translate.”[13] Why? “Behold, it is because that you did not continue as you commenced. . . . You have supposed that I would give it unto you, when you took no thought save it was to ask me. But behold, I say unto you that you must study it out in your mind; then you must ask me if it be right” (D&C 9:5, 7–8).

At issue here was more than Oliver’s attitude of teachability and humility; it was also an aptitude of intellectual application not so well developed in him as to bear results, at least not in the timely way now required. Oliver failed in the intellectually demanding work of translating because he had not thoroughly applied himself mentally to the task. As the Lord indicated, “Behold, you have not understood; you have supposed that I would give it unto you, when you took no thought save it was to ask me. But behold, I say unto you, that you must study it out in your mind; then you must ask me if it be right, and if it is right I will cause that your bosom shall burn within you; therefore, ye shall feel that it is right” (D&C 9:7–8). Joseph Smith had learned both lessons—spiritual and mental—from his previous experiences. He had been schooled in matters of character and spirit for the past nine years and from his past experience with Martin Harris and the translation of the 116 pages, clearly, in hindsight, a preparatory school of remarkable learning. Can we really expect Oliver to have learned them as well after but a few days at the task? We may wish to revise our thinking on who was the student and who was the teacher.

The intellectual demands of translating were rigorous and extremely challenging. If the experiences and testimony of the Three Witnesses are to be taken at face value, the successful translation of the Book of Mormon was neither magical nor mythical but measured and marvelous, a careful confluence of obedience, recurring repentance, and consequent revelation on the one side, and a rigorous mental exercise of intense study, recall and recognition, and trial and error on the other.”

Editors Note: “The way Brother Bennett explains the translation process above, in my opinion he makes the reading of words from a stone seem too simple, meaningless, and easy to do with any object. Key words Brother Bennett uses are Obedience, Repentance, Revelation, Mental Exercise, Intense Study, Recall, Recognition, and Trial and Error. Those words do not describe Joseph reading words off of a silly seer stone in a hat. My acronym for a Silly Seer Stone is, (SSS).

If a stone had words appear, that means someone (Angel, Christ, Nephite or who?) is having Joseph dictate, not translate. That would mean Joseph only read what he was told. That is not translation. David Whitmer, who was never a transcriber and one who never saw Joseph translate, said a piece of parchment would appear with words that would appear. Many intellectuals also say Joseph never looked at the plates while translating. Then why did Nephi and Moroni keep and protect the records? It doesn’t make sense. I believe Joseph really TRANSLATED an unknown language to English using the three objects that came in the stone box of Cumorah; Plates, Breastplate, and Spectacles. No SSS.” Rian Nelson

Rod Meldrum said, “Foundational to the Restoration is the validity of the translation of the Book of Mormon. The primary editors, Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdrey, maintained that the process was accomplished using an instrument provided centuries in advance by the Lord for the very purpose of sacred inspired translation. Some detractors claimed that Joseph abandoned the Lord’s instrument, the Urim and Thummim, for a more convenient stone in a hat. The Lord Himself in several revelations validated Joseph’s use of this instrument. Yet modern historians point to hostile witnesses to bolster their stone in the hat (SITH) narrative.” Rod Meldrum Endorsement of “These Two Stones, Fastened to a Breastplate”, by Rian Nelson Purchase Here!

Joseph’s Translation Compared to the Rosetta Stone

Bennett continues, “The specifics of translation remain a mystery, but it may be instructive to compare the work of Joseph Smith to that of his magnificent contemporary, the superlative translator of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic writing, the brilliant French linguist Jean-François Champollion. Just five years before, Champollion had finally decoded the mysterious hieroglyphs of the famed Rosetta Stone found near Alexandria by Napoleon’s army in 1799. After a lifetime of studying Coptic, Arabic, Hebrew, Greek, Egyptian, and a dozen other languages, Champollion, in his famous “Lettre à Monsieur Dacier” of September 22, 1822, exactly one year before Moroni’s initial visit, convinced the waiting world that he could read the ancient hieroglyphic writings of Egypt. As a result, Champollion, the man from Grenoble, is still rightfully revered as the father of modern Egyptology.

Whereas Champollion first naively believed that a thorough knowledge of Coptic would allow him to directly decipher ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, he gradually came to the realization that such was quite dauntingly not the case. Hieroglyphic writings were not a single alphabet; they had a wide variety of spellings for the same person or place, and they had no vowels but plenty of shorthand contractions, such as in English one might write “pkg” for “parking” or “unvsty” for “university.” Furthermore, the ancient Egyptian scribes assumed the reader was conversant with their combinations of right vowels and contractions, “but this knowledge had been lost, although Coptic gives clues to it.”[14]

After long and painstaking effort, Champollion concluded that hieroglyphs could not be read alone but in groups or clusters. Intently comparing the Greek to the Coptic, the Coptic to the demotic (a later simplified form of ancient Egyptian writing) and, by extension, the demotic to the hieroglyphic, Champollion noted that there were three times as many hieroglyphic signs as there were Greek words. Therefore, there had to be a combination or grouping of signs to convey a single meaning—in other words, consonants and syllables, essential components to phonetic expressions. Though the hieroglyphs employed no vowels, they were a combination of phonetics and pictures. Unlike others of his scientific contemporaries, such as Thomas Young of England, Champollion was now looking not just for more clues between the hieroglyphic and the demotic, but for the ability to read the maze of what constituted hieroglyphic writing.

What finally enabled Champollion to do what neither Young nor any others were able to accomplish was applying his mastery of Coptic to the problem. As one leading scholar has written, “His knowledge of Coptic enabled him to deduce the phonetic values of many syllabic signs, and to assign correct readings to many pictorial characters, the meanings of which were made known to him by the Greek text on the Stone.”[15] The system of decipherment that Champollion had been methodically developing over several years was that hieroglyphic script was mainly phonetic but not entirely so, that it also contained logograms or a sort of shorthand symbols used to write native names and common nouns from the Pharaonic period. The combination of both constituted an ancient alphabet, which he now could prove and sufficiently read or decipher. Champollion thus came to the rightful conclusion that the hieroglyphic writings were not just of the later periods of Egyptian history but of the very earliest Pharaonic era as well. He therefore decoded the entire system and showed that hieroglyphic, hieratic, and demotic all corresponded to the same language. Whereas Young may well have discovered parts of the alphabet, it was “Champollion [who] unlocked an entire language.”[16]

Editors Note: Doesn’t this paragraph confound the (SSS) spoken of before? By reading about the painstaking knowledge, wisdom, and focus of one Mr. Champollion, it confirms my belief that an unlearned Joseph needed spiritual help from the Lord to translate from an unknown language to English, a record that we may enjoy, even the Book of Mormon.

Bennett continues, “Joseph Smith, on the other hand, could barely read or write one language, English.[17] Joseph Smith had neither the time, scholarly training, nor linguistic knowledge to decode one symbol after another; indeed his mission was not to master the linguistics required to read an ancient language but to translate or convey their meanings into English. His initial work of translation consisted of copying the various “characters,” letters, phrases, or hieroglyphs found on the large plates of Nephi into some sort of working alphabet. “I copied a considerable number of them,” he records, clear evidence of the strong mental exercise and careful study he too would need before translating could actually begin. Then only gradually did he begin to use what neither Champollion nor any other translator had at their command, the Interpreters. With the aid of these ancient instruments, Joseph Smith began to translate some of the characters.”

Editors Note: There are over 9 scriptures that validate to our Spirits, that joseph used “these stones, fastened to a breastplate, constituted what is called the Urim and Thummim—deposited with the plates; and the possession and use of these stones were what constituted “seers” in ancient or former times; and that God had prepared them for the purpose of translating the book.” JSH 1:35 PDF Below:

Book of Mormon Hard Evidence Proper Translation

Bennett continues, “It would appear that the process was less one of decoding or deciphering the precise meaning of the individual characters and inscriptions found on the plates, as Champollion had so painstakingly done with the Rosetta Stone, and more one of discerning the meanings conveyed thereon and then, in addition, struggling to transliterate such meanings into acceptable, King James Bible–vintage literary English. The translators seemed to have functioned on two levels: conveying meaning from the ancient text while simultaneously suggesting wording in biblical-sounding English far beyond the reach then in Joseph’s limited grasp. Thus we might argue that Joseph Smith was not a decoder or a pure translator in the Champollion sense of the word but a transmitter/translator and writer who, with the aid of the interpreters, transposed what he saw into exquisite English prose and poetry.

For all of this, Oliver was ill prepared. The customized reprimand and gentle reproof he received in section 9 of the Doctrine and Covenants were less a rebuke and more a reminder that God had already called and prepared his prophet; what was needed now was a humble, penitent scribe and devoted supporter and trusted eyewitness to visions soon to occur. “Do not murmur my son, for it is wisdom in me that I have dealt with you after this manner; . . . it is not expedient that you should translate now. Behold it was expedient when you commenced; but you feared, and the time is past, and it is not expedient now; for, do you not behold that I have given unto my servant Joseph sufficient strength, whereby it is made up? And neither of you have I condemned. . . . Be faithful, and yield to no temptation” (D&C 9:6, 10–13). It was a lesson in repentance not missed by either man.

If Joseph and Oliver learned repentance at the outset of translating, they were repeatedly reminded of its central importance as their work progressed. Well known is David Whitmer’s 1882 remembrance of a time Joseph Smith could not translate, despite all the gifts he had at his command. “He could not translate unless he was humble and possessed the right feelings towards everyone,” Whitmer recalled.

To illustrate so you can see. One morning when he was getting ready to continue the translation, something went wrong about the house and he was put out about it. Something that Emma had done. Oliver and I went upstairs [obviously this was at the Whitmer home] and Joseph came up soon after to continue the translation, but he could not do anything. He could not translate a single syllable. He went downstairs, out into the orchard, and made supplication to the Lord; was gone about an hour—came back to the house, and asked Emma’s forgiveness and then came up stairs where we were and then the translation went on all right. He could do nothing save he was humble and faithful.[18]

Thus, to borrow B. H. Roberts’s phraseology, the translation “was not a merely mechanical process” but rather a laboratory of spiritual and mental application governed by the principles found in the very book they were now translating. Even after almost 10 years of preparation, Joseph Smith relearned the lesson that even the smallest sins or senseless hurts prevented the free flow of inspiration and revelation. By faith, faith unto repentance that led, in turn, to the guiding and revealing influence of the Spirit of the Lord, he lived his way through to the end of the translation process.”

Conclusion Joseph Smith and the First Principles of the Gospel

“I suggest a new and different perspective from that offered by some of Joseph Smith’s biographers. No where have I argued that Joseph Smith was a perfect man or without blemish. His sins and imperfections were real, and while I have not dwelt upon them in any way to discredit his life, they surely caused him a great deal of grief and hardship. Yet our theme has been that if God called a prophet, he prepared that prophet in the first principles of the gospel. The mission of Moroni, in preparing the way for the translation of the Book of Mormon, was the charge given to angelic visitors: “to minister according to the word of his command, showing themselves unto them of strong faith and a firm mind in every form of godliness. And the office of their ministry is to call men unto repentance, and to fulfil and to do the work of the covenants of the Father” (Moroni 7:30–31). Time after time, Moroni, the master prophet, trained Joseph Smith, the apprentice prophet, in matters of the soul, of honesty and integrity, in humility and patience, in repentance and forgiveness. Joseph Smith’s partners in translation, Martin Harris and Oliver Cowdery, were likewise taught the same principles and learned from hard experience that the message of the gospel had to be lived by the messengers of the gospel to have any lasting effect. Integrity, not hypocrisy, would attract the best of men and women and make for a lasting movement. This injunction was repeated all the way up to Fayette and the organization of the Church in April 1830 and indeed, for years afterward. “Preach naught but repentance:” and “the thing that will be of the most worth unto you will be to declare repentance unto this people, that you may bring souls unto me, that you may rest with them in the kingdom of my Father” (D&C 19:21; 15:6; see also 16:6). Indeed, this lesson of repentance and forgiveness would be repeated numerous times throughout the pages of later Church history, including the famous vision in the Kirtland Temple in April 1836 when the Savior pronounced once again to Joseph and Oliver, “Behold, your sins are forgiven you; you are clean before me; therefore, lift up your heads and rejoice” (D&C 110:5).”

Notes “from Joseph Smith and the First Principles of the Gospel”

[12] The Papers of Joseph Smith, vol. 1: Autobiographical and Historical Writing, ed. Dean C. Jessee (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1989), 1:10.

[13] Dallin H. Oaks, “Our Strengths Can Become Our Downfall,” BYU Speeches of the Year, June 7, 1992, 6.

[14] Lesley and Roy Adkins, The Keys of Egypt: The Obsession to Decipher Egyptian Hieroglyphs (New York: Harper Collins, 2000), 84.

[15] Ernest Alfred Wallis Budge, The Rosetta Stone in the British Museum (New York: AMS Press, 1976), 4.

[16] Richard B. Parkinson, Cracking Codes: The Rosetta Stone and Decipherment (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 40.

[17] Emma Smith later retold the experience of the translation period to her son as follows: “I am satisfied that no man could have dictated the writing of the manuscripts unless he was inspired; For, when acting as his scribe, your father would dictate to me hour after hour; and when returning after meals or after interruptions, he could at once begin where he had left off, without seeing either the manuscript or having any portion of it read to him. This was a usual thing for him to do. It would have been improbable that a learned man could do this; and, for one so ignorant and unlearned as he was, it was simply impossible” (“Last Testimony of Sister Emma,” Saints’ Herald, October 1, 1879, 290).

[18] Statement of David Whitmer to William H. Kelley and G. A. Blakeslee of Gallen, Michigan, September 15, 1882, from the Baden and Kelley debate on the divine origin of the Book of Mormon, 186, as cited in Brigham Henry Roberts, The Essential B. H. Roberts, ed. Brigham D. Madsen (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1999), 139.”

Joseph Smith and the First Principles of the Gospel Richard E. Bennett Recently published in Joseph Smith, the Prophet and Seer (Provo, UT, and Salt Lake City: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, and Deseret Book, 2010). https://rsc.byu.edu/vol-11-no-2-2010/joseph-smith-first-principles-gospel

Editor’s Note: What impresses me most about Brother Bennett’s two articles above, I can tell he has an amazing amount of love and respect for the Prophet Joseph as I do. Though a man, Joseph in my opinion and the words of scripture, “has done more, save Jesus only, for the salvation of men in this world, than any other man that ever lived in it.” D&C 135:3