Many important events happened at the Whitney store in Kirtland, Ohio. This article speaks of one of those events that happened on Feb 27, 1833. On the day before on Feb 26, 1833 a national event also happened in the United States, England and other countries. Most of us don’t understand the importance of these two closely related dates. One within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and one outside of the Church. It is quite amazing when you think about it. The Lord really does love us and shared a message with Joseph Smith on that date in Feb, 1833. a message that was not just for the Latter-day Saints, but for the entire world. “We Thank Thee O God for a Prophet.”

“To become “clean from the blood of this generation” and to set themselves apart from the world, the elders participated in ritual washings [At the Whitney Store]. After each elder washed his own face, hands, and feet, Joseph Smith washed the feet of each, following the example set by Jesus in John 13:4–17 and instructions in Doctrine and Covenants 88:138–141. Joseph washed the feet of each new member of the school and repeated the ceremony at other meetings of the School of the Prophets. Later washings and anointing’s, including foot washing, were part of preparations for the solemn assembly held in the newly dedicated Kirtland Temple, and these washings featured prominently in the solemn assembly itself.

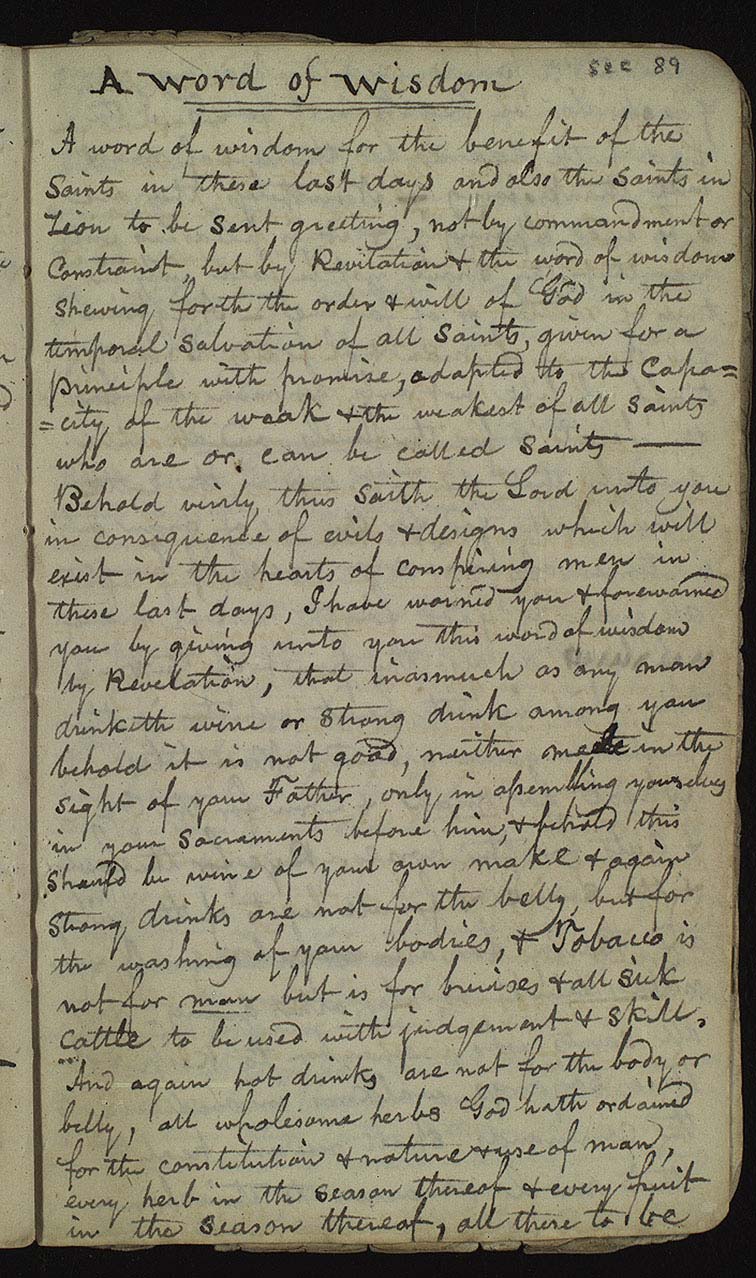

A more mundane concern with cleanliness also played a role in the School of the Prophets. One participant remembered that before each school day, “we washed ourselves and put on clean linen.” And Emma Smith’s complaints about the filth caused by the school members’ chewing tobacco led to the revelation known as the Word of Wisdom.” A School and an Endowment by Nathan Waite June 2015

I Will Pour Out My Spirit upon All Flesh

“Latter-day Saints who learn of the American health reform movements of the 1820s and 1830s may wonder how these movements relate to the Word of Wisdom. Did Joseph Smith simply draw upon ideas already existing in his environment and put them forward as revelation?

Such concerns are unwarranted. Remember that many early Latter-day Saints who took part in temperance societies viewed the Word of Wisdom as inspired counsel, “adapted to the Capacity of the weak & the weakest of Saints who are or can be called Saints.” Moreover, the revelation has no exact analog in the literature of its day. Temperance reformers often tried to frighten their hearers by linking alcohol consumption with a host of horrific diseases or social ills. The Word of Wisdom offered no such rationale. Strong drink, the revelation says simply, is “not good.” Similarly spare explanations are given for the injunctions against tobacco and hot drinks. The revelation can be understood more as an arbiter and less as a participant in the cultural debate.

Instead of arguing from a position of fear, the Word of Wisdom argues from a position of confidence and trust. The revelation invites hearers to trust in a God who has the power to deliver great rewards, spiritual and physical, in return for obedience to divine command. Those who adhere to the Word of Wisdom, the revelation says, shall “receive health in their navel and marrow to their bones & shall find wisdom & great treasures of wisdom & knowledge even hidden treasures.” These lines link body to spirit, elevating care for the body to the level of a religious principle.

In the end, some overlap between the Word of Wisdom and the health reform movement of the 19th century is to be expected. This was a time of “refreshing” (Acts 3:19), a moment in history where light and knowledge were pouring down from heaven. On the night Joseph Smith was visited by the angel Moroni for the first time, in the fall of 1823, the angel quoted a line from the book of Joel and said it was about to be fulfilled: “I will pour out my spirit upon all flesh,” the passage read (Joel 2:28; emphasis added). Insofar as temperance reform made people less dependent on addictive substances, prompting humility and righteous action, the movement surely was inspired by God. “That which is of God inviteth and enticeth to do good continually,” the Book of Mormon stated (Moroni 7:13).28 Rather than concerning themselves with cultural overlap, Latter-day Saints can joyously contemplate how God’s Spirit touched so many, so widely, and with such force. “Latter-day Saints can joyously contemplate how God’s spirit touched so many, so widely, and with such force.”

Soon after receiving the Word of Wisdom, Joseph Smith appeared before the elders of the School of the Prophets and read the revelation to them. The brethren did not have to be told what the words meant. They “immediately threw their tobacco pipes into the fire,” one of the participants in the school recalled. Since that time, the inspiration in the Word of Wisdom has been proven many times over in the lives of the Saints, its power and divinity cascading down through the years. In some ways, the American health reform movement has faded from view. The Word of Wisdom remains to light our way.”

Revelations in Context Word of Wisdom by Jed Woodworth 11 June 2013

“LIKE MANY COMMUNITIES across the nation, Kirtland, Ohio became a scene of strong temperance activity immediately before Joseph Smith dictated the Word of Wisdom, his revelatory health code (D&C 89, Kirtland, Ohio, February 27, 1833). Interestingly, the hot-bed for such reform in Ohio was the very

Western Reserve region where the Mormons lived, according to Paul H. Peterson who made a study of this phenomenon in 1972. Churches of the area became particularly interested, reports Peterson, and newspapers editorialized at length in favor of the movement. The Painesville Telegraph near Kirtland “frequently issued warnings against intemperance.” Three months before the Mormon revelation appeared, the Telegraph urged any leading citizens who still felt hesitant about this subject to set aside sectarian differences and to join in promoting temperance (P. H. Peterson, 12-13).

Christopher Crary, an early non-Mormon settler of Kirtland who was the same age as Joseph Smith, recalled that the Kirtland Temperance Society was organized on October 6, 1830. That organization proved to be “both active and influential,” and according to Crary, “‘prospered beyond the expectation of its most sanguine advocates.'” By February 1, 1833, twenty-six days before the Word of Wisdom was given, the local distillery at Kirtland, “which had existed since 1819 was closed for want of patronage . . .” (P. H. Peterson, 13, citing Christopher G. Crary, Pioneer and Personal Reminiscences [Marshalltown, Iowa:

Marshall Printing Co., 1893]

Two years later, D. Griffiths, Jr., a one-time resident of that region, reflected upon “. . . the changes wrought by the crusade and noted that many distillery houses closed down while numerous merchants gave up the sale of ardent spirits. ‘The inhabitants in general,’ said Griffiths, ‘who have much regard to their reputation practice total abstinence.’ ” (P. H. Peterson, 12, citing D. Griffiths, Residence in the New Settlements of Ohio [London: Westley and Davis, 1835], 129-30). In such a setting, the Mormon parallels which follow from the Temperance Recorder may possibly startle, but they should not surprise.

CHOLERA LINKED TO INTEMPERANCE

While analyzing the complete run of the Journal of Health in 1990, I concluded that, “. . . to some significant degree, the destroying angel in the final verse of the Word of Wisdom (D&C 89:21) can be argued to have been the cholera epidemic which swept the United States in 1832-33.” (See MP 204 for evidence, including a citation from the Temperance Recorder extra issue of November 6, 1832, examined

in this entry). Examples of this connection with cholera appeared throughout the Temperance Recorder. “We do not deem it necessary,” claimed the editor during the summer of 1832, to fill our paper with articles to prove that ardent spirit is the exciting cause to cholera; the most incredulous now acknowledge it, and the political and religious papers are filled with facts to prove it—and are spreading them before the public. Indeed every paper we receive at our office has become the advocate of the cause of temperance. The Cholera speaks out and let every tongue and pen reiterate the warning. [p. 43 (August 7, 1832 issue)] “Necessary” or not, cholera references abound in this volume: pages 15, 25 (left column), 28-29, 30 (“All spirit drinkers will be the first victims of the cholera.”), 38, 40 (illustrated below), 43 (quoted above), 44, 52, 52-53, 55, 59, 59-60, 60-61, 61, 74 and 77. [Mormon Parallels: A Bibliographic Source © 2014 Rick Grunder]

The November EXTRA issue was devoted to a presentation of statistical evidence that cholera was precipitated by intemperate behavior. It showed that of 336 persons sixteen years of age or older recorded dying from cholera in Albany during the summer of 1832, no more than ten could be shown to be nondrinkers. This study was then cited throughout subsequent temperance literature across the nation. The Journal of Health called this “a document of the highest value to those who would shun the visitations of pestilence and subsequent death.” The Journal published extracts from it in January 1833, with the speculation “that returns of a very similar nature might be made from all the places in which the cholera has prevailed.” (Journal of Health IV:152-53) Mormon Parallels: A Bibliographic Source © 2014 Rick Grunder page 1771

A notice on page 40 grabbed readers’ attention by headlining the dreaded word:

TOTAL ABSTINENCE

For the relevance of “total abstinence” to early Mormonism, see (Temperance Almanac, For . . . 1836) and related entries in this bibliography. Examples in the present Temperance Recorder occur on the printed presentation slip described in my bibliographic notes above and on pp. 20, 26, 54, 85 and 87. In addition, an article on page 36 argues that even people who are capable of temperate drinking must abstain completely, in order to support those who might otherwise drink too heavily; compare to D&C 89:3, 5.

“TOTAL ABSTINENCE” was indeed the slogan of the day. In the woodcut (below left) on the title page of this 1836 almanac, the doctrine assumed an almost revelatory character: This engraving also appeared on the back of the very widely-circulated Temperance Recorder for February 1835 (see MP 434, entry for the Temperance Recorder issue of April 2, 1833, note at end).” Mormon Parallels: A Bibliographic Source © 2014 Rick Grunder

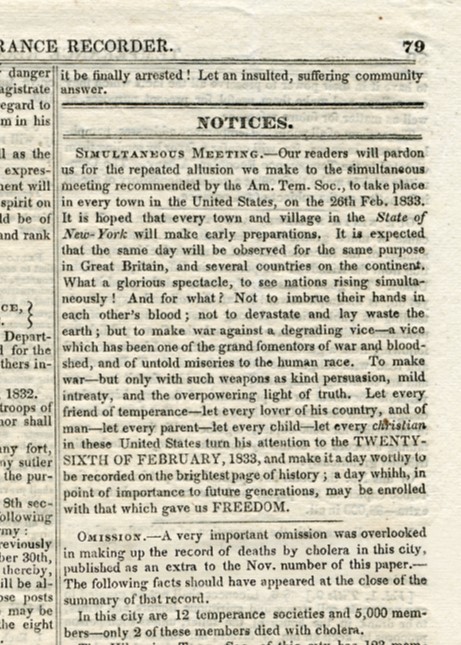

“SIMULTANEOUS TEMPERANCE MEETINGS TO BE HELD TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 26, 1833

Among Mormon parallels that I discovered in the early 1980s, none startled me more than the simple fact that the Word of Wisdom was dictated one day following the most dramatic temperance event of the nineteenth century, America’s first nationwide anti-drinking rally. The volume of the Temperance Recorder considered here contains powerful references and advertisements to that event: Page 64 reports that this event has been proposed by the Executive Committee of the American Temperance Society, convened at Boston on September 21, 1832: . . . unanimously resolved:

1. That it is highly desirable that meetings of temperance societies and friends of temperance, be holden simultaneously on some day that may be designated, in all the cities, town and villages throughout the United States.

2. That Tuesday the 26th day of February, 1833, be designated for that purpose.

3. That measures be immediately taken to accomplish the above-mentioned object. [p. 64; for full text, see MP 13 (American Temperance Almanac for 1833)] Ministers of all denominations are enjoined to read the national circular from their pulpits, calling for this February 26 meeting to be held “in all the cities, towns and villages of our country . . .” “Editors of papers and periodicals” are requested to “give publicity to this circular” in their columns. Five days later, the New York society agrees eagerly: “The President and the Executive Committee of the New-York State Temperance Society, cordially approve of the proposal . . . and . . . will immediately commence making preparations for carrying into full effect the recommendation of the National Society . . .” (at head of this entire notice: “Office New-York State Temperance Society, Albany, September 26, 1832.” p. 64)

A notice in the next issue sees the upcoming rally “as the commencement of a new era in the temperance reform, and as the first shinings of that light which shall soon cast its cheerful and happy influence over all our country . . . ,” p. 70. February 26, 1833, will be a memorable occasion . . . The spectacle which that day will present, will indeed be one of glory, and calculated to swell with emotion the breast of every one who loves his country, and who feels for the woes of those whom intemperance has made wretched. A whole nation—powerful, free, enlightened—will then rise up and with one united effort, crush beneath its feet a hideous monster, which has annually demanded the immolation of thousands and tens of thousands of victims upon its bloody and cruel altar. On that day will be solved, we trust and believe, that problem which has so long baffled the skill of European politicians, whether a

nation can govern itself, and the world be convinced that Americans can conquer, not others, but themselves. . . . . .

Fellow citizens: As one man let us rise and subdue the deadliest foe to our prosperity and happiness. Let us make such an advance as shall consecrate the 26th of February as a national jubilee, to be ever after commemorated as the day on which Americans burst the shackles of a degrading and destroying vice, and regained a moral freedom which shall perpetuate their cherished institutions till the very end of time. [p. 71]

Another notice, placed prominently on page 79 (left)(December 4 issue), enjoins, . . . Let every friend of temperance—let every lover of his country, and of man— let every parent—let every child—let every Christian in these United States turn his attention to the TWENTY-SIXTH OF FEBRUARY, 1833, and make it a day worthy to be recorded on the brightest page of history; a day which in point of importance to future generations, may be enrolled with that which gave us FREEDOM. [p. 79; early state illustrated (left) has a typo, “whihh gave us . . .”] Mormon Parallels: A Bibliographic Source © 2014 Rick Grunder page 1773

Another notice, placed prominently on page 79 (left)(December 4 issue), enjoins, . . . Let every friend of temperance—let every lover of his country, and of man— let every parent—let every child—let every Christian in these United States turn his attention to the TWENTY-SIXTH OF FEBRUARY, 1833, and make it a day worthy to be recorded on the brightest page of history; a day which in point of importance to future generations, may be enrolled with that which gave us FREEDOM. [p. 79; early state illustrated (left) has a typo, “whihh gave us . . .”] Mormon Parallels: A Bibliographic Source © 2014 Rick Grunder page 1773

In an age of conservative typography and restrained composition, this was an assertive ad: Page 81 (the front page of the January 1 issue) promotes an urgent membership drive to increase temperance society membership in the state “before the 26th of February.” Each county society should send at least three delegates “to attend the annual meeting of the State Society on the 26th of FEBRUARY next, . . .” In the annual report, town and county societies will be asked to answer eleven questions, including: “10. Did you observe the 26th of Feb.?” Page 96: “. . . No society should suffer the day to pass without notice; but even if an address cannot be had, meet and converse together respecting the evils and the remedies of intemperance; read the constitution, and devise means for the still farther [sic] progress of the work.” For examples of such addresses which were delivered, see MP 104 (Proceedings and Speeches at a Meeting for the Promotion of the Cause of Temperance . . .) and MP 198 (Ingram). Other mentions of this watershed event occur on pp. 70-71 and 87-88.

TEMPERANCE RECORDER. Published Monthly, by the Executive Committee of the New-York State Temperance Society. Albany, [New York], for April 2, 1833 [II:2]. Quarto. Paged 9-16. With strong relevance to the timing of the Word of Wisdom (D&C 89) which Joseph Smith dictated in Kirtland, Ohio, on February 27, 1833: The simultaneous meeting of the 26th February, presented a spectacle of deep interest . . . a large and cheerful audience, filled at an early hour, every part of the 2d Presbyterian Church, and many could not find room within the walls of this spacious edifice. . . . we must congratulate the friends of the cause every where, on the efforts of that day. Letters from every state in the union speak the same language, and all unite in giving this simultaneous meeting an importance that will, it is believed, result in one of the most successful efforts that has yet been devised to perfect the reform. [p. (9). The pastor of the Second Presbyterian Church, Albany, was William Buell Sprague (see DAB), who corresponded with Chief Justice John Marshall – presumably about this event – at this very time; see MP 433 (Temperance Recorder, Volume I)]

The 26th of Feb. was observed as a day of special united effort in behalf of temperance, in, we believe, every part of the Union. A whole nation then called up its energies, and the cry . . . was heard reverberating from hill to hill, and from vale to vale. It was an interesting day, and as such, will be referred to in later ages by those who shall come after us . . . [p. 14] On the 26th inst. the day appointed by the American Temperance Society for simultaneous meetings in all the cities, towns and villages of the United States, a meeting of members of Congress was holden in the Senate Chamber, at the Capitol in Washington, for the purpose of forming a Congressional Temperance Society. [p. 16; see MP 104 (Proceedings and Speeches at a Meeting for the Promotion of the Cause of Temperance . . .]

— SUBSEQUENT ISSUES of the Temperance Recorder continued to enshrine this date as a sacred anniversary to be observed. The December 1834 issue reminded readers that February 26 was still “the day of simultaneous meeting of all societies throughout the Union. We need not state the vast importance of these yearly meetings. . . . friends of the cause in various parts of the world, unite with us on the same day to promote this great work . . . ,” p. 80. — The February 1835 issue reminded readers of the February 26 meeting on its page 89. On its back page appeared the “TOTAL ABSTINENCE” engraving which lent a religious, revelatory tone to this movement (see MP 431, Temperance Almanac, For . . . 1836, for illustration and discussion). Below that engraving in this issue was reproduced a certificate endorsed with the facsimile signatures of then-living Presidents Madison, Jackson and John Quincy Adams, advocating temperance, though not specifying if they themselves abstained.

TEMPERANCE RECORDER. Albany, [New York], September, 1834 [III:7]. 27 X 21½ cm. Paged [49]-56. One of the several copies examined was unopened and untrimmed, and bore a contemporary manuscript distribution note in the upper margin of the first page, “Doct T M Nott 8 Copies.” Contains an engaging, first-hand account of a poor family’s rescue from ruin, thanks to a local temperance meeting. As in the Word of Wisdom’s warning about “evils and designs . . . of conspiring men in the last days” leading people to drink (D&C 89:4), we read of similar “wicked and designing men” in this story of a reformed drunkard who was nearly destroyed by his old companions who plotted carefully to get him drunk again. Once stimulated, he called for more and yet more, till these wretches had the pleasure of seeing him who had so long stood firm, reeling from the shop, to mar at once all that was pleasant and peaceful at home. . . . The dram-seller knew my husband—knew of his reform—that from being a nuisance to the town, he had become an orderly and respectable citizen—and now that he had been seduced from the right way, instead of denying him the cause of all our former misery instead of a little friendly advice—with his usual courteous smile, he put the fatal glass into his hand. . . . But he was not thus to become the dupe of wicked and designing men. . . . He called one evening to see the president of the temperance society, confessed his weakness in yielding to temptation . . . requested to have his name, which had been erased from the temperance list, renewed, and promised never again to violate the pledge. [p. 51]

My source for much of this information above is a 2,307 page book called Mormon Parallels: A Bibliographic Source © 2014 Rick Grunder. It is a fantastic resource of Mormon related events paralleling with modern day events.

The following is from Revelations in Context Word of Wisdom by Jed Woodworth 11 June 2013

Tobacco

“This episode in the Whitney store occurred in the middle of a massive transformation within western culture. In 1750, personal cleanliness and hygiene were infrequent, haphazard practices, mostly the concern of the wealthy and aristocratic. By 1900, regular bathing had become routine for a large portion of the population, especially the middle classes, who had adopted gentility as an ideal. Tobacco spitting shifted from being a publicly acceptable practice among most segments of the population to becoming seen as a filthy habit beneath the dignity of polite society. In the midst of this cultural shift, at the very moment when everyday people started to concern themselves with their own cleanliness and bodily health, the Word of Wisdom arrived to light the way.

D&C 89 on JosephSmithPapers.org

D&C 89 on JosephSmithPapers.org Review the Annotated Book of Mormon Here:

Review the Annotated Book of Mormon Here:

The scene in the School of the Prophets would have been enough to give any non-tobacco user like Joseph Smith cause for concern. Joseph’s wife, Emma, told him that the environment concerned her. He and Emma lived in the Whitney store, and the task of scrubbing the spittle from the hardwood fell upon her. She may have complained of being asked to perform this thankless task, but there was also a more practical consideration: “She could not make the floor look decent,” Brigham Young recalled. The stains were impossible to get out. The whole situation seemed less than ideal for those who were called of God as these elders were, especially when we remember that the room with the filthy floor was Joseph’s “translation room,” the same place where he received revelations in the name of God. Joseph began inquiring of the Lord about what could be done, and on February 27, scarcely a month after the school started, he received the revelation later canonized as Doctrine and Covenants 89. The answer was unequivocal: “Tobacco is not for man but is for bruises & all sick cattle; to be used with judgement & skill.”

Strong Drinks

Tobacco was just one of a host of substances pertaining to bodily health and cleanliness whose merits were hotly debated on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean at the time the Word of Wisdom was received. Discussion was so frequent because abuse was so widespread. Frances Trollope, a British novelist, reported disdainfully in 1832 that in all her recent travels in the United States, she hardly ever met a man who was not either a “tobacco chewer or a whisky drinker.”

Drinking, like tobacco chewing, had clearly gotten out of hand. For centuries nearly all Americans had consumed large quantities of alcoholic beverages, much like their European counterparts. The Puritans called alcohol the “Good Creature of God,” a blessing from heaven to be imbibed in moderation. Alcohol was consumed at virtually every meal, in part because the unpurified water of the time was so unhealthy. Home-brewed beer was a favorite, and after 1700, British-American colonists drank fermented peach juice, hard apple cider, and rum either imported from the West Indies or distilled from molasses made there. By 1770, per capita consumption of distilled spirits alone—to say nothing of beer or cider—stood at 3.7 gallons per year.

The American Revolution only exacerbated this reliance on alcohol. After molasses imports were cut off, Americans sought a substitute for rum by turning to whiskey. Grain farmers in western Pennsylvania and Tennessee found it cheaper to manufacture whiskey than to ship and sell perishable grains. As a consequence, the number of distilleries grew rapidly after 1780, boosted by settlement of the corn belt in Kentucky and Ohio and the vast distances to eastern markets. To the astonishment of observers like Trollope, Americans everywhere—men, women, and children—drank whiskey all day long. American consumption of distilled spirits climbed precipitously, from two and a half gallons a person in 1790 to seven gallons in 1830, the highest amount of any time in American history and a figure three times today’s consumption rate.

This elevated alcohol consumption offended religious sensibilities. As early as 1784, both Quakers and Methodists were advising their members to abstain from all hard liquor and to avoid participation in its sale and manufacture. A more aggressive temperance movement took hold among the churches in the early decades of the 19th century. Alcohol became viewed more as a dangerous tempter and less as a gift from God. In 1812, the Congregational and Presbyterian churches in Connecticut recommended strict licensing laws limiting the distribution of alcohol. Lyman Beecher, a leader in this reform movement, advocated even more extreme measures, endorsing full abstinence from alcoholic beverages. The idea soon became a central plank of the American Temperance Society (ATS), organized in Boston in 1826. Members of the organization were encouraged to sign a temperance pledge not just to moderate their alcohol intake but to abstain altogether. A capital “T” was written next to the names of those who did so, and from this the word “teetotaler” was derived. By the mid-1830s, the ATS had grown to well over a million members, many of them teetotalers.

Encouraged by the ATS, local temperance societies popped up by the thousands across the U.S. countryside. Kirtland had its own temperance society, as did many small towns. Precisely because alcohol reform was so often discussed and debated, the Saints needed a way of adjudicating which opinions were right. Besides rejecting the use of tobacco, the Word of Wisdom also came down against alcoholic beverages: “Inasmuch as any man drinketh wine or Strong drink among you behold it is not good, neither mete in the sight of your Father.”

Nevertheless, it required time to wind down practices that were so deeply ingrained in family tradition and culture, especially when fermented beverages of all kinds were frequently used for medicinal purposes. The term “strong drink” certainly included distilled spirits such as whiskey, which thereafter the Latter-day Saints generally shunned. They took a more moderate approach to milder alcoholic beverages like beer and “pure wine of the grape of the vine, of your own make.” For the next two generations, Latter-day Saint leaders taught the Word of Wisdom as a command from God, but they tolerated a variety of viewpoints on how strictly the commandment should be observed. This incubation period gave the Saints time to develop their own tradition of abstinence from habit-forming substances. By the early 20th century, when scientific medicines were more widely available and temple attendance had become a more regular feature of Latter-day Saint worship, the Church was ready to accept a more exacting standard of observance that would eliminate problems like alcoholism from among the obedient. In 1921, the Lord inspired President Heber J. Grant to call on all Saints to live the Word of Wisdom to the letter by completely abstaining from all alcohol, coffee, tea, and tobacco. Today Church members are expected to live this higher standard.

Hot Drinks

American temperance reformers succeeded in the 1830s in no small part by identifying a substitute for alcohol: coffee. In the 18th century, coffee was considered a luxury item, and British-manufactured tea was much preferred. After the Revolution, tea drinking came to be seen as unpatriotic and largely fell out of favor—the way was open for a rival stimulant to emerge. In 1830, reformers persuaded the U.S. Congress to remove the import duty on coffee. The strategy worked. Coffee fell to 10 cents a pound, making a cup of coffee the same price as a cup of whiskey, marking whiskey’s decline. By 1833, coffee had entered “largely into the daily consumption of almost every family, rich and poor.” The Baltimore American called it “among the necessaries of life.” Although coffee enjoyed wide approval by the mid-1830s, including within the medical community, a few radical reformers such as Sylvester Graham and William A. Alcott preached against the use of any stimulants whatsoever, including coffee and tea.

The Word of Wisdom rejected the idea of a substitute for alcohol. “Hot drinks”—which Latter-day Saints understood to mean coffee and tea—“are not for the body or belly,” the revelation explained. Instead, the revelation encouraged the consumption of basic staples of the kind that had sustained life for millennia. The revelation praised “all wholesome herbs” and explained that “all grain is for the use of man & of beasts to be the staff of life . . . as also the fruit of the vine that which beareth fruit whether in the ground or above ground.” In keeping with an earlier revelation endorsing the eating of meat, the Word of Wisdom reminded the Saints that the flesh of beasts and fowls was given “for the use of man with thanksgiving,” but added the caution that meat was “to be used sparingly” and not to excess.”

Revelations in Context Word of Wisdom by Jed Woodworth 11 June 2013

“Like many other revelations in the early Church, Doctrine and Covenants 89, also known today as the Word of Wisdom, came in response to a problem. In Kirtland, many men in the Church were called to preach in various parts of the United States. They were to cry repentance unto the people and gather in the Lord’s elect. To prepare these recent converts for their important labors, Joseph Smith started a training school called the School of the Prophets, which opened in Kirtland on the second floor of the Newel K. Whitney mercantile store in January 1833.

Every morning after breakfast, the men met in the school to hear instruction from Joseph Smith. The room was very small, and about 25 elders packed the space. The first thing they did, after sitting down, was “light a pipe and begin to talk about the great things of the kingdom and puff away,” Brigham Young recounted. The clouds of smoke were so thick the men could hardly even see Joseph through the haze. Once the pipes were smoked out, they would then “put in a chew on one side and perhaps on both sides and then it was all over the floor.” In this dingy setting, Joseph Smith attempted to teach the men how they and their converts could become holy, “without spot,” and worthy of the presence of God.”

Revelations in Context Word of Wisdom by Jed Woodworth 11 June 2013 (I organized this information to hopefully give the reader a combined and organized narration of the article by Jed Woodworth and the bibliography by Rick Grunder)