Two thousand years ago an ancient army walked across North America’s largest river. In September 1837 Robert E. Lee finished his survey of the Des Moines Rapids. The survey is one of the best surveys ever made in the early 1800s. From thousands of soundings, and measurements for the depth of the river’s water, it is possible to identify a route that a Lamanite Army took when it walked across the River Sidon. (Alma 43) That crossing was close to Zarahemla. Thank you, Robert E. Lee, for helping us to confirm the location of that great city.

It’s a piece of history that you did not know. Why? Because no one from our Church took the time to study Robert E. Lee’s 1837 Survey and compare it to the text of the Book of Mormon. Why? Because our scholars for the last 50 years spent their time and money looking in the jungles of Central America for evidence of the Book of Mormon. What a sad story. The truth can only come out of the ground if you are looking in the right place. Moroni knew and he told Joseph Smith. The truth will make us free. The truth will unite us.” John C. Lefgren PhD CEO Heartland Research Group in Pennsylvania.

While Robert E. Lee was near the De Moines Rapids in 1834 doing survey work (His survey ended in Sept of 1837), Joseph Smith was just 90 miles south on the Mississippi River crossing with Zion’s Camp near Louisiana, MO. Also on June 4, 1834 Joseph was writing a letter to his beloved Emma from Atlas, Illinois on the banks of the Mississippi which said, “The whole of our journey, in the midst of so large a company of social honest and sincere men, wandering over the plains of the Nephites, recounting occasionally the history of the Book of Mormon, roving over the mounds of that once beloved people of the Lord, picking up their skulls & their bones, as a proof of its divine authenticity… During our travels we visited several of the mounds which had been thrown up by the ancient inhabitants of this country-Nephites, Lamanites, etc.” Joseph Smith Papers Letter to Emma Smith, 4 June 1834 Page 56

Yes, the evidence for a major city at this location of the Mississippi River continues to mount. It is a natural place for a city at the end of the “road” where all kinds of trade could transpire.

A Letter to BYU Geography Department

April, 2020

Dr. _____________________________

Department of Geography

Brigham Young University

Provo, Utah

Dear Dr.___________________________

I am writing with a very unusual idea. I have been working with the Heartland Research Group on Book of Mormon Evidences in the US. I am amazed at what we are finding in terms of evidence for Book of Mormon geography. BUT, today we came across survey maps made by General Robert E. Lee of the Mississippi River right next to Nauvoo. This was Lee’s first field assignment after graduating top of his class at West Point. The only place on the Mississippi river where one could walk across the river was at the Des Moines Rapids literally next to Nauvoo. Lee had about 120 men doing surveys and soundings (15,000 soundings) of these rapids for 3 years only a few years before the Mormons settle the area.

We believe these rapids would have been a barrier to ancient people too that were using the river as a navigational route through this part of the US. It is likely that a major city once was located in this area on the Des Moines side of the river and interestingly, in the D&C 125:3 the Lord commanding Joseph Smith to name the city on the opposite side of the river from Nauvoo – Zarahemla. We have found ~20 foot tall earth mounds in the area, hundreds of burial mounds, thousands of arrow heads and battle axes in the area and we are exploring a possible Temple site. This year we will be flying the area with 2 to 3 inch resolution color infrared imagery and if funding permits, we will be flying selected locations with LiDAR imagery. The imagery will be flown with about 70% overlap so that orthomosaics can be created and used as base maps in a GIS for subsequent geospatial analysis. We will be purchasing a magnetometer to collect readings at sub 1.0 inch resolution and we know from past work in Ohio and Europe that fire pits will jump out at us in the subsurface imagery. If there were a major ancient city in this area, we expect to also find hundreds of buried fire pits.

I was asked by my colleagues why has BYU not had any students do a study on the Des Moines rapids to pull together the significance of this area to our early European navigators of the Mississippi (we believe it may have been called the Sidon River anciently), and possibly a critical navigation barrier to the ancient Nephites and Lamanites? The study could be done without any reference to possible Book of Mormon connections, but I am trying to plant some thoughts in your mind. I know we have been taught for 50 years that the Book of Mormon geography took place in Central America, but after considerable study, many are starting to abandon that idea and looking in what we believe is the Land of Promise as Joseph Smith claimed. In the past year, the church took a neutral position on the Book of Mormon geography, and the reason for this is that the evidence for Central America has not been as compelling as one is led to believe, and increasing evidence is mounting for the Hopewell Native Americas (the Mound Builders) being the Nephites in the US. The fact that the church took a neutral stand means our church leadership is not convinced the Hill Cumorah is in Guatemala. I believe it is in New York state. The neutral stand also does not mean that we are not to keep looking.

We are presently in a fund raising effort and are starting to connect with the promising funding possibilities. If all goes as we hope, we will have funding and the possibility of some very interesting aerial photographs and LiDAR data within this year.

I just wanted to see if you think there is any interest in discussing these ideas and maybe developing some interesting project opportunities for faculty and students?

Best wishes,

Kevin Price PhD

Professor Emeritus Kansas State University

Senior Scientist

Heartland Research Group

785-393-5428

[email protected]

A response would be wonderful. Even better a response with a confirmation to throw a few thousand dollars our way along with the giving millions to Book of Mormon Central for the worn out digging for some news about the Book of Mormon in Mesoamerica. What have we found in Mesoamerica. Huge pyramids that aren’t even spoken of in the Book of Mormon. Nephites built with earth and wood. As Hugh Nibley has said,

“What most impressed me last summer on my first and only expedition to Central America was the complete lack of definite information about anything. Never was so little known about so much… It is just a fact of life that no one knows much at all about these oft-photographed and much-talked-about ruins…

Counterparts to the great ritual complexes of Central America once dotted the entire eastern United States, the most notable being the Hopewell culture centering in Ohio and spreading out for hundreds of miles along the entire length of the Mississippi River. These are now believed to be definitely related to corresponding centers in Mesoamerica…” Hugh Nibley

The Des Moines Rapids

In Exploring the Book of Mormon in America’s Heartland by Rod Meldrum pg 80-81

“The Des Moines Rapids between Nauvoo, Illinois on the east and Montrose (Zarahemla) and Keokuk, Iowa on the west was formed by a hard natural limestone shelf that extended across an 11 mile stretch of the Mississippi river. It severely limited Steamboat traffic through the earl 19th century. Prior to the building of locks and dams that have raised water levels 18-20 feet, it was the first location upstream from the Gulf of Mexico where the Mississippi river could be crossed… on foot. Historical records state that these rapids had an average depth of only 2.4 feet*, with most of the crossing being more shallow, especially during late summer, fall and dry seasons…

*”The Mississippi in its natural state widens from 2,500 feet (760 m) to 4,500 feet (1,400 m) in width at Nauvoo as it drops 22 feet (6.7 m) over 11 miles (18 km) over shallow limestone rocks to the confluence with Des Moines. According to records its mean depth through the rapids was 2.4 feet (0.73 m) and “much less” in many places.” Wikipedia

…Why is this important? This would have been one of the most strategic locations in North America due to this crossing of a significant barrier to travel, the Mississippi River. Trade would also occur here bringing goods and people together from across the continent.

This location would also be of strategic importance in securing against foreign invasion. An ancient army would of necessity be faced with either swimming or rowing their men across to launch an attack, which in the case of the Book of Mormon could mean many thousands of men awaiting portage. The element of surprise in battle would be lost if a week were required to ferry men across the river. This major river crossing would, then, be a critical strategic location either to defend of to conquer, by allowing or restricting access to either side.

CROSSING THE MISSISSIPPI ON HORSEBACK

On August 8, 1842, a Warrant was served by Governor Carlin for the arrest of Joseph Smith and Porter Rockwell who had been charged with the near fatal shooting of Gov. Lilburn Boggs. Joseph and Porter went into hiding, knowing their innocence and that this was just another attempt to thwart the work of the Lord.

From Dean C. Jesse’s The Papers of Joseph Smith, in the Illinois journal we read from the entry Aug. 11th, “It is very evident that the whole business is but another evidence of the effects of prejudice, and that it proceeds from a persecuting spirit, the parties having signified their determination to have Joseph taken to Missouri whether by legal or illegal means.” The journal continued, “12 August 1842 – Friday – This AM it appears still more evident that the whole course of Proceedings of Gov. Carlin and others is illegal”

A stratagem was conceived to trick the Sheriff and his Deputies. The journal states,” Accordingly Joseph’s new horse which he rides, (which he named Joe Duncan after the unsupportive former Governor of Illinois) was got ready and Wm. Walker proceeded to cross the river in sight of a number of Persons. One chief design in this procedure was to draw the attention of the Sheriffs and public, away from all idea that Joseph was on the Nauvoo side of the river.”

The next day, “A report came over the river that there is a several small companies of men in Montrose, Nashville, Keokuk, etc., in search of Joseph. They saw his horse go down the river yesterday and was confident he was on that side.” The Mississippi River was shallow enough on this late summer day to ride a horse across it at this location.” Exploring the Book of Mormon in America’s Heartland by Rod Meldrum pg 80-81

Bruce Lloyd

Bruce Lloyd2 days agohttps://www.loc.gov/resource/g3700m.gct00284/?sp=187&q=mississippi+river+iowa&r=0.021,0.325,0.069,0.044,0 has a detailed map of the survey between Nauvoo/Montrose at the upper end and about 10 miles downstream to Keokuk, IA. About 100 miles north of Nauvoo is the 2nd Barrier of the Mississippi River. It is called Rock Island Rapids between LeClaire, Iowa and Rock Island Illinois (about 14 miles). Robert E Lee also surveyed the Rock Island Rapids in Sep and Oct 1837 using a longer pole of 14 feet vice 10 feet at Nauvoo.

See https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3700m.gct00284/?sp=153&r=0.692,0.154,0.346,0.205,0 Migrating Buffalo could have crossed the Mississippi River at either of these 2 sites. The Nauvoo site is about 10 miles long and the Grand Island Rapids site is about 14 miles.” Bruce Lloyd

The Cherokee Landscape and Buffalo Economy

By Wild South | March 4, 2016 By Lamar Marshall, Wild South Cultural Heritage Director Source

At the dawn of the historical era in North America, perhaps earlier than 1400, several ecological events coalesced to change the way of life for native peoples living east of the Mississippi River. For centuries, native people created agriscapes across parts of Eastern America, which included clearing fields, creating grasslands and savannas, and promoting rivercane in large canebrakes.

Rivercane was the highest-yielding native pasturage in the Southeast and provided winter forage for elk, deer, and buffalo. Large savannas along the Mississippi River were maintained by systematic annual burning, with canebrakes being burned every 7 to 10 years. Open woodlands and park-like savannas were widespread.

At some point in time, buffalo crossed the Mississippi River and filled an ecological niche that spanned at least three or four hundred years. This niche is believed to have resulted from a population crash of Pre-Columbian native peoples by European-introduced disease that may have killed 90% of as many as 1.7 million people. Rivercane likely invaded abandoned fields after the crash of native populations. The Cherokees were estimated at 32,000 in 1685, 16,000 in 1700, and 11,200 in 1715

The abandoned towns, fields, and grasslands in the East were perfect habitat for migrating Western buffalo (Bison bison bison,), with herds peaking between conservative estimates of 30 million and more popular estimates of between 45 and 60 million. Records tell that these wild buffalo were shy and advanced away from human settlements. Several crossing places on the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers allowed for eastward expansion through Louisiana and Mississippi to the Gulf States, as well as the Great Lake region and northern states. Biologists agree that the Eastern Buffalo was the same as the Plains buffalo (Bison bison bison) and crossed the Mississippi several hundred years ago.

Although archaeological evidence is scant regarding buffalo material remains, there is overwhelming recorded testimony to substantiate its presence across all regions of the Cherokee territorial claim. Besides meat, the Cherokee and all Southeastern tribes utilized the buffalo for leather, war shields, moccasins, robes, sleeping rugs, bull-boats, horned headdresses, horn spoons, and woven wool clothes and accoutrements.

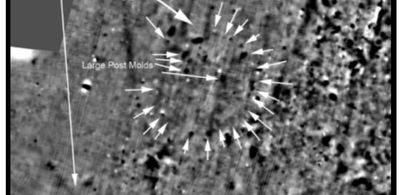

Magnetic Signatures in Ground from Ancient Fires

“First, we are looking for Zarahemla. That is a clear statement required for a thesis. Nothing wrong here. Second, we know where to look. We are looking at the site that Joseph Smith identified as Zarahemla. This then is the test of that hypothesis. Nothing wrong with that approach. We are looking for a confirmation of the truth of Joseph Smith’s statement. Our methods are clear. We know that ancient people kept fires to cook their food, to heat their homes and to bring light to dark places. We know that the heat from these fires changed the magnetic signatures of soil and rock. These changes can be measured with a magnetometer. The SENSYS equipment can survey 100 acres per day within grids that are 1/4″ x 1/4”. Each data point will have GPS coordinates and will measure differences in magnetic forces by +/- 1nT (nanotesla). These readings will be able to identify the location of old fire pits.

The Book of Mormon informs us that in AD 320 there was a Nephite army from the Land of Zarahemla that had 30,000 men. Taking that number as our best indicator, we estimate that the population of Zarahemla was at least 100,000 people. We can find fire pits. We believe that there should be one fire pit for every 10 people or that within a mile or so of the city’s center there would have been 10,000 fire pits. We know that German technology has worked very well on several sites including Stonehenge. We have our own experience with SENSYS from the mounds of Ohio. If we can find anything, we can find fire pits that were kept 1,600 years ago. I like science and I am willing to pay for it. If you can make improvements to our research, I welcome your informed opinion and not just off the cuff speculations. We expect that God’s ancient promises will be fulfilled — “the truth shall spring out of the earth.” Wayne May Ancient America Magazine

Zarahemla, Capital City of a Land that is Choice Above All Other by Wayne May

“You have to look for it before you can find it. We believe that there are good reasons to look on the west bank of the Mississippi in Lee County, Iowa. The reasons come from a reading of the Book of Mormon as it relates to the movements of those ancient people as well as from the surface. We already know that there is ancient human habitation in the area as evidenced by existing earth mounds.

In December 2018 we found 7 roundhouses in Glenford, Ohio that are 2,000 years old. It took less than a day to do this investigation. The results were accepted and printed by the Ohio Archaeological Society. This Society was founded in 1941 and is the oldest and largest archaeological society in the United States. The Society was organized to discover and conserve archaeological sites and material in Ohio; to seek and promote a better understanding among students and collectors of archaeological material, both professional and non-professional; and to disseminate knowledge on the subject of archaeology. The Society’s membership is made up of people from all walks of life, from every state in the nation, many foreign countries, including libraries, historical societies, colleges, and universities. This is the standard of work that the Heartland Research Group has already done. We will apply the same standards of research to our search for the City of Zarahemla. We are working with the best technology in the world coming from Germany. We are ready to begin the search in earnest. Donate $10 a month to help Wayne May find the Lost City of Zarahemla.

There is no other place in the world that can produce more consumable calories of food than the million square miles that are part of the Mississippi and St. Lawrence watersheds. Think of St. Louis, Cincinnati, Columbus, Chicago, Detroit, Madison, and Toronto. North America could not be a great power without its Heartland. Would there be any of the ancient civilizations of Egypt, India, and China without the Nile, Ganges, and Yellow river basins? The Romans were a great empire only as long as they controlled the grain from the Nile and waterways of the European Great Plains. Ancient empires were rooted in soils of riverbasins that provided a surplus of food for the support of large armies. Large armies in the Book of Mormon required good soils and plenty of water from the Heartland.

The large armies in AD 384 at the end of the Book of Mormon required at least 2,000 x 700,000 = 1,400,000,000 pounds of foodstuff to be delivered on the riverways up to Cumorah. That magnitude of food could only have come from the great watersheds of the Mississippi and St. Lawrence. The Great City of Zarahemla was great because it was on the Sidon River. The City of St. Louis is great because it is on the Mississippi River.

My friends, if you want to find the City of Zarahemla, you have to look in a place where a great city would have been supported by great agricultural lands. Those lands, anciently and currently, have soil, water, and climate to produce more than 10 million calories per acre. The early Europeans were surprised to see the tens of thousands of acres of corn that Native Americans cultivated in the St. Lawrence River basin. There are more than 5,000 ancient earth mounds in Ohio which were built by people who controlled the great agricultural regions of the river basins. Of all the places in the world, any good farmer would soon recognize that this place is “bountiful”, “a land of promise”, and “choice above all other”.

We are working with people who have degrees in higher education and have developed the latest technologies for locating the remains of cities and human habitation.

We are using the tools of modern archaeology to locate evidence for the ancient city of Zarahemla. We have successfully used SENSYS Technolgies from Germany in discovering six round houses in Ohio that are 2,000 years old.

We are limiting our research to 10,000 acres of farmland that are on the west bank of the Mississippi across from Nauvoo. Wayne May will take the lead in providing direction for the discovery of the most important city in the Book of Mormon.

“The events of the Book of Mormon took place over about one thousand years and in an area of more than a billion acres. By far, Zarahemla is the most frequently mentioned place name in the Book of Mormon. By focusing on 7,000 acres in Lee County, Iowa, as the likely location for the Lost City of Zarahemla, the research will be confined to less than one-thousandth of a percent of the total area found within the geography of the ancient people in the Book of Mormon. Just as the city of Rome occupied a small space in the entire area of the Roman Empire, so, Zarahemla was in a little place in the total geographical area of the Book of Mormon. Also, like Rome, Zarahemla was a vital place tying together as much as one million square miles of territory. For hundreds of years, Zarahemla was the center of government, military, and trade. These facts confirm the idea that if anyone can find the location of Zarahemla, it would become an essential geographical site for the historicity of the Book of Mormon.” Wayne May

D&C SECTION 125

Revelation given through Joseph Smith the Prophet, at Nauvoo, Illinois, March 1841, concerning the Saints in the territory of Iowa.1–4, The Saints are to build cities and to gather to the stakes of Zion.

1 What is the will of the Lord concerning the saints in the Territory of Iowa?

2 Verily, thus saith the Lord, I say unto you, if those who call themselves by my name and are essaying to be my saints, if they will do my will and keep my commandments concerning them, let them gather themselves together unto the places which I shall appoint unto them by my servant Joseph, and build up cities unto my name, that they may be prepared for that which is in store for a time to come.

3 Let them build up a city unto my name upon the land opposite the city of Nauvoo, and let the name of Zarahemla be named upon it.

4 And let all those who come from the east, and the west, and the north, and the south, that have desires to dwell therein, take up their inheritance in the same, as well as in the city of Nashville, or in the city of Nauvoo, and in all the stakes which I have appointed, saith the Lord.

Alma 43- See Map Below

I also include Alma 43 about the battle of Moroni against the Lamanites at the River Sidon. The battle is done in a shallow part of the River, (Maybe Des Moines Rapids or more south towards St. Louis).

Alma 43:25 Now Moroni, leaving a part of his army in the land of Jershon, lest by any means a part of the Lamanites should come into that land and take possession of the city, took the remaining part of his army and marched over into the land of Manti.

26 And he caused that all the people in that quarter of the land should gather themselves together to battle against the Lamanites, to defend their lands and their country, their rights and their liberties; therefore they were prepared against the time of the coming of the Lamanites.

27 And it came to pass that Moroni caused that his army should be secreted in the valley which was near the bank of the river Sidon, which was on the west of the river Sidon in the wilderness.

Alma 43 Continued at the end of the blog:

“What a Beautiful Country It Is”

Robert E. Lee on the Mississippi By Rick Britton

“The old steamboat sat alongside the rapids, perched atop the river rocks that had stoved in her thin hull. The lower deck was partly submerged, but her upper cabin deck, along with its staterooms, was dry and habitable. Yawning holes in the steamer’s flooring, holes through which the engines had been hoisted, gave notice of her recent abandonment. And perhaps served as a reminder that her predicament—along this treacherous stretch of the Mississippi—was not unique

While members of the surveying party fished from the stern for pike and blue catfish, their leader—a thirty-year-old lieutenant of engineers—composed a letter on one of the stranded ship’s few remaining tables. “I assure you we were not modest,” he wrote to a fellow engineer of his appropriation of the vessel, “and [we] helped ourselves to everything that came our way. . . . I need not tell you what a beautiful country it is and I think at some time, some future day, must be a great one. You would scarcely recognize it. Villages have sprung up everywhere and some quite pretty ones too. . . . Some ten years hence, many . . . will have grown into cities. . . . The formation of a good channel through these rapids will be of immense advantage to the country, and great anxiety seems to be felt on the subject.”[note 1] The date was October 11, 1837, the site a section of the Mississippi’s Upper Rapids near the mouth of the Rock River. The letter-writer, of course, was Robert E. Lee, and this letter in particular, to Andrew Talcott, would prove prophetic. Many of the river towns indeed grew into cities for the coming decade of the 1840s would feature a massive boom in Mississippi-borne commerce. Commercial tonnage transported on the upper Mississippi, in fact, tripled in the ten years following 1839 (from 400,000 to 1.2 million).[note 2] Many would later claim that the Virginia engineer’s work on the river played a significant role in that growth.

Robert E. Lee is best remembered, of course, as the commander of the Confederacy’s premier fighting force—the Army of Northern Virginia. At the helm of the A.N.V. for almost three years, he not only turned back several Federal attempts at Richmond but also launched two invasions of the North. Lee’s performance during the May of 1863 Chancellorsville Campaign, despite being outnumbered two-to-one, is still studied as a masterpiece of military science. He is also well remembered for the position he accepted after the war. As president of Washington College, Lee set the standard for the South in terms of acquiescence to the conflict’s outcome, and reconciliation between the previously warring sections. By comparison, however, little is remembered of Lee’s first profession—that to which he devoted the most years of his life—engineering. Perhaps his finest efforts in the Army Corps of Engineers were those directed toward improving navigation on the “Father of Waters”—the Mississippi River.

Born at Stratford Hall in Westmoreland County on January 19, 1807, Robert E. Lee was home-schooled until he was thirteen. At that age he entered the Alexandria Academy and came under the tutelage of William B. Leary, an Irishman who for the next three years provided the young Virginian with a rudimentary classical education. “In mathematics he shone,” wrote biographer Douglas Southall Freeman, “for his mind was already of the type that delighted in the precise reasoning of algebra and geometry.”[note 3]

Seeking to further his education, but not wanting to burden his mother with the expense, Lee then sought an appointment to the United States Military Academy. With the endorsement of five U.S. senators and three representatives to his favor—as well as, of course, the military reputation of his father, General Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee—Robert E. Lee was appointed to West Point in March of 1824. The War Department letter, however—signed by then secretary, John C. Calhoun—notified him that because of the large number of applicants, he could not be admitted until July of the following year. In order to avoid getting rusty, Lee studied mathematics during the intervening period under Benjamin Hallowell, the headmaster of a new boys’ school in Alexandria. “He was a most exemplary pupil in every respect,” Hallowell noted years later. “His specialty was finishing up. He imparted a finish and a neatness, as he proceeded, to everything he undertook. One of the branches of mathematics he studied with me was Conic Sections, in which some of the diagrams are very complicated. He drew the diagrams on a slate: and although he well knew that the one he was drawing would have to be removed to make room for another, he drew each one with as much accuracy and finish, lettering and all, as if it were to be engraved and printed.”[note 4]

Robert E. Lee arrived at West Point in June of 1825. Thirty-seven miles up the Hudson from New York City, the United States Military Academy then consisted of but a handful of fairly plain structures arranged upon a commanding plateau 190 feet above the river. Historian Emory Thomas has called the institution “a military monastery, a single-sex community of vigorous study, rigid discipline, and Spartan living.”[note 5] But it was much more. The Academy was the first and, at the time, the finest engineering school in the United States—the special province of the Army Corps of Engineers. The two, in fact, were inseparable, having been created simultaneously by an 1802 act of Congress which read that the Corps “shall be stationed at West Point . . . and shall constitute a military academy.” The act also stipulated that the Army’s principal engineer would be West Point’s superintendent.[note 6]

During the demanding four-year course of study, Robert E. Lee proved that diligence and self-control were his in abundance. Early on he displayed a special proficiency in mathematics. In his second year, in fact, he was made an acting assistant professor of that subject, and spent many long hours tutoring those cadets who were struggling. Mathematics, naturally, was at the heart of the West Point curriculum and formed the foundation for the courses in engineering and the sciences. At the Academy, Lee studied, among other subjects, chemistry, physics, optics, mineralogy, and astronomy. The courses on advanced mathematics covered trigonometry, calculus, analytical and descriptive geometry, and those pesky conic sections. (One of the math textbooks, by the way, was Treatise on Descriptive Geometry and Conic Sections by French engineer Claudius Crozet, one of the founders of the Virginia Military Institute.)

The final term at West Point featured an intense focus on engineering. The comprehensive course was divided into five sections—field and permanent fortifications, the science of artillery, grand tactics, and civic and military architecture. This last topic covered drafting, the various orders of architecture, the design and construction of arches, bridges, buildings, canals, and other public works, and a detailed description of the machines used in that construction. “In this subject [Lee] found especial satisfaction,” wrote Freeman. “As among the sciences, the applied meant more to him than the theoretical. . . . When he began engineering he may have felt, also, that this more fully than anything else represented the profession he had chosen.”[note 7]

Robert E. Lee graduated second in the class of 1829—without incurring a single demerit—and, exercising the right accorded class leaders, asked to be assigned to the Engineers. Because engineering had fascinated him more than any other subject it would now become his profession. Thanks to his hard work, Lee was commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers.

The Army wasted no time in putting the twenty-two-year-old to work. In August of 1829 Robert E. Lee was posted to Cockspur Island in the Savannah River, twelve miles downstream from the port city of Savannah. There he helped prepare for the construction of a large earthwork—eventually named Fort Pulaski—which would command the river. Lee remained at Cockspur for the 1829 and 1830 work seasons, spending much of his time, legend has it, armpit deep in the muddy Savannah. His final months there he was under the command of Lieut. Joseph Mansfield, who was later killed at the Battle of Sharpsburg leading a Union Army corps.

Lee was next assigned to Fortress Monroe in Virginia. Located on Old Point Comfort, a narrow spit of land forming the extreme tip of the peninsula between the James and York Rivers, it had been the site of a military work since 1609. Lee reported for duty in May of 1831. The following month, furlough in hand, Lee was married to Mary Anne Randolph Custis at Arlington. Returning to Fort Monroe with his bride—but a few weeks prior to the slave insurrection led by Nat Turner—Lee went to work as assistant to Captain Andrew Talcott, the post’s constructing engineer. The fort was nearly complete but the outworks and moat needed attention. Additionally, Lee supervised work on Fort Calhoun, a steadily sinking mound of stone just offshore. During his three-year stay on the Virginia Peninsula he designed buildings, wharves, and fortifications; oversaw the preparation of accounts and reports; learned how to deal with laborers; and gained a great amount of experience in estimating construction costs. He had arrived with but limited experience—he was now completely qualified to independently direct a large engineering project.[note 8]

Unfortunately, the Corps of Engineers had other plans. Far from receiving an independent project, Lee was instead ordered to Washington. In November of 1834, he reported for duty in the capital city as assistant to the Army’s chief engineer, Brigadier General Charles Gratiot (pronounced “grass-shot”). Initially excited about the assignment, he quickly discovered that the office work was sheer drudgery—a daily shuffling of accounts, budgets, queries, clarifications, complaints, reports, and vouchers. On the plus side, Lee was in charge of the office whenever the general was away, which was frequently, and the proximity to Arlington meant he could ride to work and back across the Potomac. Despite one shining moment, however—a summer of 1835 assignment surveying the Ohio-Michigan border—Lee became extremely frustrated with his position, as well as with the Corps itself.

“You ask what are my prospects in the Corps?” he wrote Andrew Talcott on February 2, 1837. “Bad enough—unless [the Corps] is increased and something done for us. . . . As to what I intend doing, it is rather hard to answer. There is one thing certain, I must get away from here. . . . I am waiting, looking and hoping for some good opportunity to bid an affectionate farewell to my dear Uncle Sam, and I seem to think that said opportunity is to drop in my lap like a ripe pear.”[note 9] Luckily for Lee, and Uncle Sam, that pear had just ripened.

The independent assignment Lee longed for lay out west, on the mighty Mississippi. In the 1830s the railroads had yet to conquer the West—the region’s rivers, therefore, still served as its principal highways. Only thirty-some years had passed since the Louisiana Purchase, however, and commerce along the upper section of the Mississippi River was just getting up a head of steam. St. Louis had welcomed its first steamboat in 1817, but it was underpowered. Steamboats with more horsepower began plying the “Father of Waters” in the 1830s but the upper Mississippi—the portion above the mouth of the Ohio—posed several significant navigational problems. Specifically, two long sets of dangerous rapids were forcing vessels—at times of low water—to lighten their loads and reduce their draft, before attempting passage. Many steamers, despite this measure, were being lost to the rocks. One of the rapids, eleven miles long, was upstream from where the Des Moines River empties into the Mississippi near Keokuk, Iowa. The other, a fifteen-mile white-knuckler, lay just above the mouth of the Rock River at Rock Island, Illinois.

There was another, entirely different, problem at St. Louis. Founded by the French in the 1760s—on the Mississippi’s right bank where a forty-foot-high limestone bluff commands the water—St. Louis had boasted over 14,000 residents in the census of 1830. River commerce was its lifeblood—the city’s entire riverfront, in fact, was one continuous bustling wharf. By the 1830s, however, that harbor was endangered—the very real possibility existed that St. Louis would become landlocked. Just opposite the city, a large sand and silt island had grown in the Mississippi River. Over a mile in length, 500 yards wide, and thick with cottonwood trees, it was known as Bloody Island because of the large number of duels fought there. In 1830, for example, Maj. Thomas Biddle had faced off against the Hon. Spencer Pettis—a Missouri member of the 21st Congress—after being infuriated over charges Pettis had made against Biddle’s brother, Nicholas Biddle, president of the Bank of the United States. On August 27, the two met on Bloody Island, beyond the jurisdiction of local authorities. Both, unfortunately, were mortally wounded at the first exchange.

The problem with the island, of course, was not the affairs of honor being settled there. By the early 1830s, the Mississippi’s current was beginning to cut along the eastern, or Illinois, side of the island. During any major flood season, it was feared, the mercurial river might shift its main channel in that direction. Additionally, as the river in front of the city slowed and shallowed, another large sandbar—Duncan’s Island, just as big as its bloody brother—was building up below the harbor and fast approaching. When these two land masses merged, St. Louis would be stranded about a mile away from its livelihood.

In 1833, city leaders had paid John Goodfellow almost 3,000 dollars to plow up the islands. It was thought that the river, when high, would then wash away the loosened sand. When that plan failed the mayor wrote to the House Committee on Roads and Canals asking for assistance from the Federal government. Three years later, in 1836, Congress appropriated first $15,000 and then an additional $50,000 to solve the growing problems at St. Louis. That year, too, Robert E. Lee’s superior, General Charles Gratiot—a proud native of St. Louis and one of four Louisiana Territory boys appointed to West Point by President Thomas Jefferson—spent several weeks personally examining the river. Gratiot believed that the Corps of Engineers could solve the problems along the upper Mississippi, the rapids as well as the islands at St. Louis, and at first assigned Captain Henry Shreve to the task. Shreve—who had made a name for himself by developing a steam-driven snagboat—was extremely busy, however, clearing the western rivers. Gratiot then remembered that back east, at Corps headquarters, his assistant was not only very capable but also very eager to get out into the field.[note 10]

Lee’s orders for this, his first independent assignment, were dated April 6, 1837. Because his wife was expecting a baby, however—their third—he did not depart until mid June. From Arlington Lee, now a first lieutenant, journeyed to Philadelphia to purchase the necessary surveying equipment, then by way of the Pennsylvania Canal to Pittsburg, where he boarded a steamer and descended the Ohio to Louisville. His traveling companion—and assistant for this engineering project—was Second Lieutenant Montgomery C. Meigs, but one year out of West Point. (A native of Georgia, Meigs later served as quartermaster general of the Federal Army during the Civil War.) At Louisville Lee met up with Captain Shreve and inspected the equipment the experienced engineer had ordered for improving the rapids. This included two “machine boats” especially designed for raising submerged rocks, and an open barge in which to transport them. These were not quite completed so Lee directed that they follow him to St. Louis. At Louisville, too, First Lieutenant Lee, according to Meigs, “organized and outfitted a strong surveying-party of river-men.”[note 11]

Arriving at St. Louis on August 5, 1837, Lee and Meigs took up rooms in a hotel—“excellently kept though the building itself is bad,” Lee noted—and made a preliminary investigation, on foot, of their immediate surroundings. The Virginian was not impressed with St. Louis. “It is,” he wrote, “the [most expensive] and dirtiest place I was ever in. Our daily expenses about equal our daily pay.”[note 12] A week later he complained to his wife: “It is astonishingly hot here, thermometer 97 degrees in the House.” The dust “is now only ankle deep in the streets,” but “put in motion by the slightest wind . . . penetrates every where.”[note 13] The city’s saving grace, according to Lee, was its pretty girls, which he had yet to encounter but knew must be somewhere.

After sixteen days in St. Louis, Lee and Meigs, along with a fourteen-man surveying party, headed upriver. One hundred and fifty miles upstream, at the Des Moines Rapids, “the party attempted to pass . . . in their steamer,” Meigs wrote in the third person, “and quickly experienced the difficulties of the navigation by finding themselves fast on the rocks. . . . All efforts to float the steamer failed, and the party proceeded to make their survey of these rapids while using the steamer as a base of operations, the surveying-parties leaving the steamer in small boats in the morning and returning at night.”[note 14] Their work involved collecting data at the rapids—sounding the water depth at various intervals, taking sightings for an accurate map, etc.—so that the problem could be approached scientifically. Low water—during three months of the year—made passage all but impossible. Lee planned to blast a permanent, year-long-lasting channel through the white water.

When not working the engineers fished amongst the rocks, and penned long letters home. They also admired the untouched, unimproved countryside. The land along the upper Mississippi had yet to be surveyed or brought into the market. When the party tired of living aboard the steamer Lee quartered the men in an abandoned log cabin nearby. He and Meigs, meanwhile, “took up our blankets and walked a short mile to [a so-called city] composed of the worst kind of a small log cabin which contained the Proprietor and the entire population. Here we were kindly received and accommodated.”[note 15] His host, Lee wrote his wife, “the Nabob of this section of country,” was a “hard featured man of about fifty, a large talker, and has the title of Doctor, whether of Law, Medicine or Science, I have never learned but infer all three.”[note 16] This gentleman told Lee of his plans for a mill, a distillery, and a bridge spanning the Mississippi.

From the Des Moines Rapids the party next proceeded another 100 miles upstream, to the tail end of the Rock Island Rapids. “There they discovered another steamer wrecked upon a rock,” wrote Meigs. “Lieutenant Lee made this wreck his base of operations during the survey of the upper rapids. . . . About the end of October the work on this part of the river was finished and they returned to the Des Moines Rapids on a passing steamer. At these rapids they found the banks lined with birch-bark canoes and Indian tepees, a tribe of Chippewas having assembled there to receive the fall distribution of presents from the agents.”[note 17] Picking up their original steamboat, the party rode the current back to St. Louis.

The Lee-Meigs surveying party returned to the river town on October 8. The surveys of the upper rapids had convinced Lee that channels could be cut through them without too much trouble. Now it was necessary to produce the requisite maps and write up the recommendations. It was also time to tackle the largest portion of Lee’s assignment: the Mississippi at St. Louis. Therefore—after renting the second story of a levee-facing warehouse as an office, and turning over the map illustration to Meigs and Henry I. Kayser, a German-born cartographer—Lee focused his attention on saving the harbor. First, wrote Meigs, “parties were placed in the field on each bank of the river. Signals were established, and the river was thoroughly triangulated and sounded from the mouth of the Missouri to some distance below St. Louis.”[note 18] (Meigs makes the task sound simple, but he is referring here to at least twenty miles of river.)

With the harbor data thus collected, Lee devised a scheme to deepen the original channel in front of the city and wash away Duncan’s Island. Based, in part, upon the investigations performed by Shreve and Gratiot, Lee presented his formal report on December 6, 1837. It was deceptively simple. From the Illinois bank of the Mississippi, a 600-yard-long dam, or dike, would be laid to the head of Bloody Island. Hopefully, this structure would permanently divert the river to the Missouri side of the sandbar and eventually attach Bloody Island to the State of Illinois. The western face of the island below this dam was to be shielded by a stone revetment one-third of a mile long. Additionally, at the foot of Bloody Island another dam—this one at least 1,000 yards long, running parallel with the banks of the Mississippi—would be constructed to throw the full force of the river against the head of Duncan’s Island.[note 19] Lee admitted that the dams could only be built with “great difficulty,” and estimated the total cost at $158, 554.

Lee’s proposal, if it worked, would manhandled the Mississippi into its original channel—by cutting off its alternative route, east of Bloody Island—and then use the river itself for the demise of Duncan’s Island. Obviously, the construction of the two dams was crucial to the plan’s success. For each, Lee proposed driving two parallel rows of pilings, twenty-five feet apart, into the riverbed. The space between them was to be filled with sand and small stones. On both of the outer faces, brush weighted with rocks would be dumped into the water until it extended out a good forty feet. It was anticipated that sand and silt would soon thereafter fill in all the open spaces.[note 20]

Taking stock of the river’s problems, and putting together his report, had consumed the balance of 1837. So, after preparing for the upcoming work season—including ordering four more flatboats—Lee and Meigs headed back east. Henry Kayser, the German mapmaker, would hold down the fort until Lee returned. The trip home to Arlington was memorable for Lee because it included a ride on the newly opened Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. It was Lee’s first. In Washington, Lee and Meigs parted company. Although the two engineers would never again work together Montgomery Meigs would later profoundly affect the Lee family.” Rick Britton

Alma 43 Continued

I also include Alma 43 about the battle of Moroni against the Lamanites at the River Sidon. The battle is done in a shallow part of the River, (Maybe Des Moines Rapids or more south towards St. Louis).

Alma 43:25 Now Moroni, leaving a part of his army in the land of Jershon, lest by any means a part of the Lamanites should come into that land and take possession of the city, took the remaining part of his army and marched over into the land of Manti. (Manti dark orange, Zarahemla in bright orange in map below)

26 And he caused that all the people in that quarter of the land should gather themselves together to battle against the Lamanites, to defend their lands and their country, their rights and their liberties; therefore they were prepared against the time of the coming of the Lamanites.

27 And it came to pass that Moroni caused that his army should be secreted in the valley which was near the bank of the river Sidon, which was on the west of the river Sidon in the wilderness.

Alma 43- See Map Below

Alma 43 Continued- See Map Below

Alma 43;30 And he also knowing that it was the only desire of the Nephites to preserve their lands, and their liberty, and their church, therefore he thought it no sin that he should defend them by stratagem; therefore, he found by his spies which course the Lamanites were to take.

31 Therefore, he divided his army and brought a part over into the valley, and concealed them on the east, and on the south of the hill Riplah;

32 And the remainder he concealed in the west valley, on the west of the river Sidon, and so down into the borders of the land Manti.

33 And thus having placed his army according to his desire, he was prepared to meet them.

34 And it came to pass that the Lamanites came up on the north of the hill, where a part of the army of Moroni was concealed.

35 And as the Lamanites had passed the hill Riplah, and came into the valley, and began to cross the river Sidon, the army which was concealed on the south of the hill, which was led by a man whose name was Lehi, and he led his army forth and encircled the Lamanites about on the east in their rear.

36 And it came to pass that the Lamanites, when they saw the Nephites coming upon them in their rear, turned them about and began to contend with the army of Lehi.

37 And the work of death commenced on both sides, but it was more dreadful on the part of the Lamanites, for their nakedness was exposed to the heavy blows of the Nephites with their swords and their cimeters, which brought death almost at every stroke.

38 While on the other hand, there was now and then a man fell among the Nephites, by their swords and the loss of blood, they being shielded from the more vital parts of the body, or the more vital parts of the body being shielded from the strokes of the Lamanites, by their breastplates, and their armshields, and their head-plates; and thus the Nephites did carry on the work of death among the Lamanites.

39 And it came to pass that the Lamanites became frightened, because of the great destruction among them, even until they began to flee towards the river Sidon.

40 And they were pursued by Lehi and his men; and they were driven by Lehi into the waters of Sidon, and they crossed the waters of Sidon. And Lehi retained his armies upon the bank of the river Sidon that they should not cross.

41 And it came to pass that Moroni and his army met the Lamanites in the valley, on the other side of the river Sidon, and began to fall upon them and to slay them.

42 And the Lamanites did flee again before them, towards the land of Manti; and they were met again by the armies of Moroni.

43 Now in this case the Lamanites did fight exceedingly; yea, never had the Lamanites been known to fight with such exceedingly great strength and courage, no, not even from the beginning.

44 And they were inspired by the Zoramites and the Amalekites, who were their chief captains and leaders, and by Zerahemnah, who was their chief captain, or their chief leader and commander; yea, they did fight like dragons, and many of the Nephites were slain by their hands, yea, for they did smite in two many of their head-plates, and they did pierce many of their breastplates, and they did smite off many of their arms; and thus the Lamanites did smite in their fierce anger.

45 Nevertheless, the Nephites were inspired by a better cause, for they were not fighting for monarchy nor power but they were fighting for their homes and their liberties, their wives and their children, and their all, yea, for their rites of worship and their church.

46 And they were doing that which they felt was the duty which they owed to their God; for the Lord had said unto them, and also unto their fathers, that: Inasmuch as ye are not guilty of the first offense, neither the second, ye shall not suffer yourselves to be slain by the hands of your enemies.

47 And again, the Lord has said that: Ye shall defend your families even unto bloodshed. Therefore for this cause were the Nephites contending with the Lamanites, to defend themselves, and their families, and their lands, their country, and their rights, and their religion.

48 And it came to pass that when the men of Moroni saw the fierceness and the anger of the Lamanites, they were about to shrink and flee from them. And Moroni, perceiving their intent, sent forth and inspired their hearts with these thoughts—yea, the thoughts of their lands, their liberty, yea, their freedom from bondage.

49 And it came to pass that they turned upon the Lamanites, and they cried with one voice unto the Lord their God, for their liberty and their freedom from bondage.

50 And they began to stand against the Lamanites with power; and in that selfsame hour that they cried unto the Lord for their freedom, the Lamanites began to flee before them; and they fled even to the waters of Sidon.

51 Now, the Lamanites were more numerous, yea, by more than double the number of the Nephites; nevertheless, they were driven insomuch that they were gathered together in one body in the valley, upon the bank by the river Sidon.

52 Therefore the armies of Moroni encircled them about, yea, even on both sides of the river, for behold, on the east were the men of Lehi.

53 Therefore when Zerahemnah saw the men of Lehi on the east of the river Sidon, and the armies of Moroni on the west of the river Sidon, that they were encircled about by the Nephites, they were struck with terror.

54 Now Moroni, when he saw their terror, commanded his men that they should stop shedding their blood.

ALMA 44:21 Now the number of their dead was not numbered because of the greatness of the number; yea, the number of their dead was exceedingly great, both on the Nephites and on the Lamanites.

22 And it came to pass that they did cast their dead into the waters of Sidon, and they have gone forth and are buried in the depths of the sea.“

(Notice here how the word Sea is related with the River. Sea could be a River and a River could be a Sea)

Another Amazing Des Moines River Map of 1829

Map above is an 1829 Survey by Napoleon Bonaparte Buford of the section of the Mississippi River, showing the Des Moines Rapids between Nauvoo, Illinois and Keokuk, Iowa-Hamilton, Illinois.

The Des Moines Rapids was one of two major rapids on the Mississippi River that limited Steamboat traffic on the river through the early 19th century.

The survey was commenced by Napoleon B. Buford of the US Army Corps of Topographical Engineers in 1829 and corrected by Henry Miller Shreve in 1836.

The map was published as part of a concerted effort between 1825 and 1843 to survey and improve commercial navigation and flooding on major American Rivers, undertaken by the US Army

Napoleon Bonaparte Buford (January 13, 1807 – March 28, 1883) was an American soldier, Union general in the American Civil War, and railroad executive. He was the half-brother of the famous Gettysburg hero, John Buford, but never attained his sibling’s military distinction.

Survey Description

Map shows settlements and some structures along the border between Iowa and Illinois during the early nineteenth century. Relief shown by hachures, (short parallel lines used in hill-shading on maps, their closeness indicating steepness of gradient), and contours, (an outline, especially one representing or bounding the shape or form of something). Depths shown by shading and spot heights. Scale not given.

Physical Description

1 map : col. ; 16 x 32 cm.

Creation Information

Shreve, Henry Miller, 1785-1851 1836.

Context

This map is part of the collection entitled: Map Collections from the University of Texas at Arlington and was provided by University of Texas at Arlington Library to The Portal to Texas History, a digital repository hosted by the UNT Libraries. It has been viewed 607 times, with 5 in the last month.

Abraham Lincoln used Robert E. Lee’s 1837 Survey Map

‘Lincoln was already an experienced railroad lawyer when he accepted the case. From 1852 to 1860, he handled cases for the Illinois Central. Three times as an attorney for the Alton & Sangamon Railroad, he won cases that eventually came before the U.S. Supreme Court. He also had previously argued two cases in the U.S. District Court involving the question of the obstruction of navigable rivers by the construction of bridges. In one of these cases, he was legal counsel on the side of the river interests.

Lincoln almost always sought out the fundamental facts on which to base his case. He had a reputation of being very well prepared. He apparently was not satisfied with the explanations of the accident given by the bridge master, bridge engineer, and others. A few days after he took the case, he traveled to Rock Island to see the bridge firsthand. He walked out onto the bridge and, as the story goes, met a boy sitting out on one of the spans. He asked the boy if he lived around here and the boy replied, “Yes, sir. I live in Davenport. My dad helped build this railroad.” Lincoln then asked the boy if he knew much about the river. When the boy answered in the affirmative, Lincoln laughed and said, “I’m mighty glad I came out here where I can get a little less opinion and more fact. Tell me now, how fast does this water run under here?

Lincoln and the boy figured out the speed of the river current under the bridge by timing how fast a log traveled from the island to the bridge. The boy who told this story was Benjamin R. Brayton, son of B. B. Brayton, resident engineer on the project, and who later was also a Rock Island engineer. Lincoln, with his customary thoroughness, studied other information concerning the current, speeds, eddies, and the traffic of the river, including the survey of the river done by Robert E. Lee. During the trial, Lincoln scored points with the jury with his intimate knowledge of the measurements of the bridge and the river.

Rock Island Bridge used Lee’s Survey

The Rock Island Bridge was built for the purpose of uniting the Chicago and Rock Island Railroad, which had just reached Rock Island from Chicago in 1854, and the Mississippi and Missouri Railroad in Iowa, which was building from Davenport toward Council Bluffs on the western end of the state during 1853. Proponents of the project touted Rock Island as an ideal location for the bridge as it provided a direct rail link between the city and state of New York, the Mississippi Valley, and the Far West. Project engineers, drawing on an 1837 topographical survey by Lt. Robert E. Lee and other surveys, deemed the site ideal.

Because the boundary between Illinois and Iowa was in the center of the main channel of the Mississippi River and both railroad’s charters differed on their legal origin and terminal points, special legislation and a new charter was necessary to unite the two railroads. The problem was solved by an act of the Illinois legislature in 1853 incorporating the Railroad Bridge Company with the power to “build, maintain, and use a railroad bridge over the Mississippi River . . . in such a manner as shall not materially obstruct or interfere with the free navigation of said river.” This condition would become a crucial point in future litigation.

The construction of the bridge started on July 16, 1853, and lasted for three years. The construction involved three sections—a bridge across a narrow portion of the river between the Illinois shore and the island, a line of tracks across Rock Island, and the long bridge between the island and the Iowa shore.” Prologue Magazine, Bridging the Mississippi The Railroads and Steamboats Clash at the Rock Island Bridge Summer 2004, Vol. 36, No. 2 By David A. Pfeiffer