Our friend, Brian Stutzman wrote the following article for LDS Living and several publications. Firm Foundation would like to acknowledge this wonderful story by sharing it with our readers.

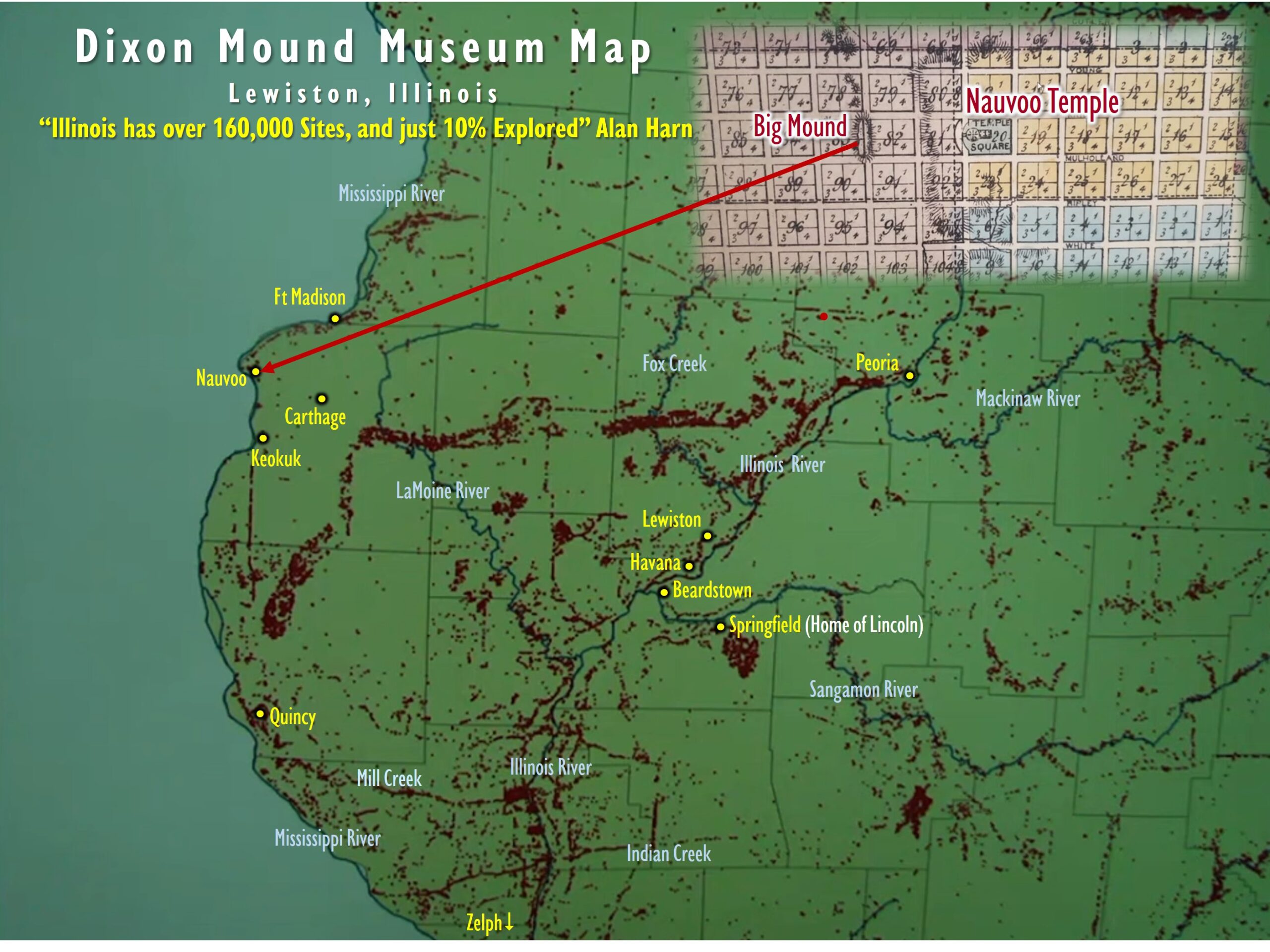

Mr. Stutzman sent me an email saying, “I followed closely the approval by the city of Nauvoo for the new visitor center [Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints approved].

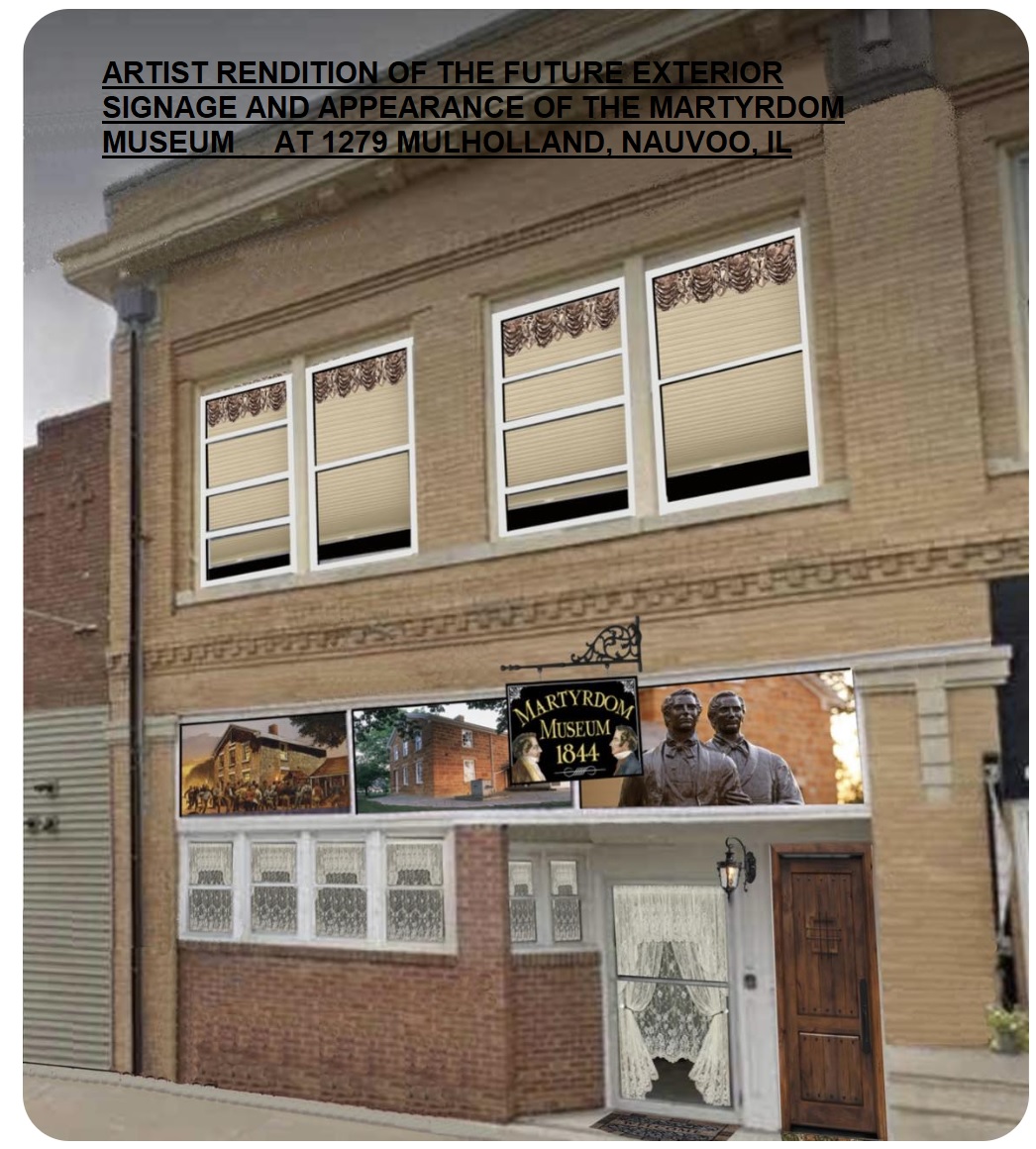

It will be on the west side of the temple just a bit north. Our building [Brian Stutzman] is on the block east of the temple. Right next door to where the Expositor building was!…

We will see you [Firm Foundation] in the fall, and hope to see you in Nauvoo summer 2025 or after. Our focus will be telling the Martyrdom story. It is not being told in Nauvoo or Carthage. Such as the Expositor or the court case after, or my favorite the story of Eliza Graham [See article below], who was the 18 year old church member who was the waitress at the Warsaw House who served the mob who killed Joseph and Hyrum the night of the martyrdom. She testified against the 5 mob leaders the next year.

The Bravest Woman in Church History That You’ve Never Heard Of

by Brian Stutzman

“Eliza Jane Graham may be the bravest woman in church history that you have never heard of. Eliza, a member of the church, was just 19 years old when she became the star witness for the prosecution in the trial of those charged in the death of the Prophet Joseph Smith.

It all started when Eliza was a teenager. Her family joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and moved to Nauvoo, Illinois. Her aunt and uncle, Samuel and Ann Graham Fleming, not church members, moved to Warsaw, Illinois. Warsaw was a small but thriving city just 18 miles south of Nauvoo. Situated on the Mississippi River, Warsaw became the hotbed of anti-Mormon feelings in the 1840s. Warsaw Signal newspaper editor Thomas Sharp and others fanned the flames of hate and religious bigotry toward the church and especially its leaders.

The Flemings owned and operated the Fleming Inn, also known as the Warsaw House Hotel. It was a hotel, boarding house, restaurant, saloon, and livery completely with stables. It was at this Warsaw House Hotel that Eliza found employment as a waitress, working for her aunt and uncle. Although a faithful church member, Eliza had not broadcast her religious affiliation to those in town.

The Night To Always Be Remembered

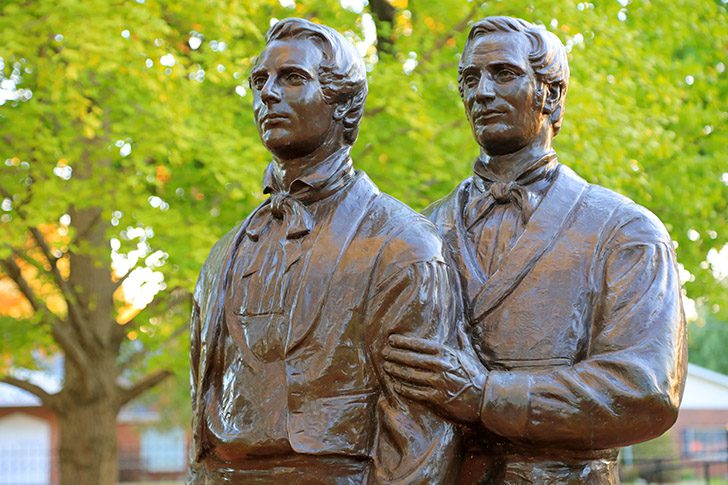

Normal life came crashing to an end for Eliza on the night of June 27, 1844, when a mob, mostly from Warsaw, attacked the Carthage Jail and martyred the Prophet Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum Smith, the Patriarch. Earlier that day, a group of men, about 200, had left Warsaw and gone north toward Nauvoo. They had erroneously heard that Governor Ford had been kidnapped by church members and was awaiting rescue.

The Warsaw group, made up of two military detachments from Warsaw and one from nearby Green Plains, was greeted by a messenger from the governor as they approached a crossroads known as Golden’s Point, about halfway between Warsaw and Nauvoo. It was close to noon. The messenger ordered the Warsaw group to disassemble and return home.

But instead of immediately following the governor’s orders this group decided to discuss their next move. Some, such as the group’s doctor Charles Hay, advocated returning to Warsaw, which he and a few others did. However, Thomas Sharp and Levi Williams, a colonel in the militia from Green Plains, and others, urged the mob to re-direct to Carthage. They reminded the mob that not only did they not like Joseph Smith, but they also had political problems with Governor Ford. Because of this, some told the mob that if they went to Carthage and killed Joseph Smith, the church members in Nauvoo might be so enraged they might immediately kill Governor Ford, thereby potentially removing two enemies of the mob from Warsaw. After more debate, it was decided that the majority of the group would march on to Carthage.

Disguising themselves with mud and gunpowder, this group entered Carthage just after 5 pm. What followed is well known to church members: the cold-blooded murders of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. After this treachery was complete, a shout of “the Mormons are coming” was heard and the cowardly mob hastily returned to Warsaw.

Around 9pm, the mob began to return to Warsaw and went directly to the Warsaw House Hotel where Eliza Jane Graham was on duty in her waitress job. No one in town knew what had occurred in Carthage until Thomas Sharp, the first mob member to return, came into the restaurant and asked for a glass of water. Sharp waited at the Warsaw House Hotel’s restaurant until dozens of his co-conspirators joined him. Eventually, some 50-60 mob members gathered, ordered food and drink, and celebrated their wicked deed.

Eliza Jane Graham, just 18 years old at the time, listened in horror as different members of the group began describing what had happened. She gathered herself and paid close attention to what the various mob members were saying. She memorized where they sat, what they said, and how they said it. At the same time, her aunt, the proprietor of the Warsaw House, remained in the back kitchen cooking and preparing the requested meals. Her husband Samuel was in Boston on business.

As the evening got later and more alcohol was consumed, the group began to get louder and more boisterous. Jacob C. Davis and William Grover openly discussed the killing of the Smiths with Grover bragging that he had been the actual killer of “Old Joe.” Little did the crowd know that Eliza Graham was a church member and was taking mental notes of the various conversations. The boastful crowd finished dinner and the last of the group dispersed about 2am. A few, including Davis and Grover, retired upstairs to their rented rooms at the Warsaw House.

Almost immediately, Eliza left her employment and moved to Nauvoo to live with her parents. It was a traumatic time in Nauvoo as church members mourned the deaths of their prophet leader and the church’s patriarch. Governor Ford, horrified that his promise of safety given to the Smith brothers was not honored by the mobs and militias in the area, promised swift legal justice.

The Trial

A few months later, in October 1844, Eliza’s uncle Thomas Graham, a non-church member, was asked to sit on a Grand Jury that was convened in Carthage. The purpose of the Grand Jury was to see if there was enough evidence to warrant a trial be held on this matter. On Saturday, October 26, 1844, this Grand Jury decided to charge nine people for the crime committed in Carthage. These nine were Thomas Sharp, Levi Williams, William Grover, Jacob Davis, Mark Aldrich, John Wills, William Voras, John Allen, and William Gallaher.

Some of those who faced these charges were celebrated as heroes. For example, Gallaher and Voras were bought new suits by the residents of Green Plains. But others felt those charged were criminals, including Governor Ford, who wrote that the mob committed “mutiny and treachery.” Out of these nine that were charged, four fled the area, leaving only Sharp, Williams, Grover, Davis, and Aldrich to stand trial about seven months later. All of these five lived in Warsaw except for Levi Williams, who lived, as noted, in nearby Green Plains.

In regards to this case, the prosecutor acknowledged that it might never be known who actually pulled the trigger at Carthage. Therefore, the charge filed was not murder but rather “the conspiracy to commit murder.” Therefore, instead of seeking the actual murderers, the charge would instead be against community ringleaders and others who conspired to stir up the mob to commit the crimes. The charges, therefore, were brought against prominent men in the area who had influence enough to lead the crowd. Regarding this charge, Thomas Sharp clearly had the lead role in inciting anti-Mormon feelings and whipping the mob up to march on to Carthage on June 27, 1844.

Court cases were not regularly heard in this part of the country in the 1840s, but rather cases were heard twice a year in what was known as “Court Week.” For this case, Court Week began in Carthage in May 1845. Mormon leaders counseled their members not to attend, noting that not even Joseph Smith was safe in that town. The prosecution wanted Mormon leaders to come and testify, but the leaders avoided being served subpoenas as they realized the trial was likely to be a sham anyway. For good measure, however, the anti-Mormons posted a mob of nearly 1000 people outside Carthage in an effort to keep any Mormons or their friends from attending and possibly testifying.

The case was officially called “The People vs. Levi Williams,” and the courthouse was overflowing when the proceedings began. The audience was a rough crowd and many openly carried rifles and other weapons inside and around the courthouse.

The mob and their guns intimidated the judge and the prosecution. At the start of this trial, it was noted this was an important case where the lives of five men were at stake and the eyes of the nation were watching. The judge was Richard Young, an experienced and respected former member of the Illinois Supreme Court.

The attorney for the prosecution was Josiah Lamborn and the defendants were represented by Oliver H. Browning, Archibald Williams, and Calvin Warren, all of Quincy, and William Richardson of Rushville. Warren, ironically, had previously represented Joseph Smith several times. While attendance wasn’t kept, it is safe to say that many residents of Warsaw were at the trial to see the fate of their neighbors, friends, and militia leaders. In fact, the prosecutor publicly acknowledged that the crowd was anti-Mormon when, near the start of the trial, he told the jury that, “There are hundreds here I have no doubt who are ready to applaud you and rejoice with you if you should return a verdict of not guilty against these men.”

After the prosecution had called a few witnesses who didn’t give much testimony, they called on their star witness Eliza Graham. Mr. Lamborn had recently found and interviewed her and asked her to come to the trial. Even though Brigham Young and the other church members felt Carthage was unsafe and had decided not to be involved in the trial, Eliza went and testified. She was just 19 years old when she gave her testimony.

Once on the stand, Eliza recounted her experience the night of the crimes. She told of how she served those boasting of the murders. Attorney Lamborn asked Eliza to tell the jury what was said by those she served. She testified that someone said “he had killed Old Jo” but then another would insist that no, they had killed Smith. Eliza testified she heard William Grover say he had committed the murders. She said that all around the Warsaw House the men were bragging and rejoicing concerning their deeds. In her concluding remarks, Eliza testified that Sharp and Davis had said “we have finished the leading men of the Mormon Church.”

Eliza also testified she had often heard Thomas Sharp threatening to kill the Smiths. Sharp had even allegedly threatened this on the morning of the murders. Eliza held strong during cross-examination and that she only found out a week prior that she was to testify at this trial.

Her testimony was received with enough prejudice that the defense was able to convince the jury to discount it. Writing about Miss Graham some years later, former Warsaw resident and famous town son John Hay shared what is probably more of a community memoir, since he was only a child at the time of the trial. Concerning Graham, John Hay wrote, “The evidence of Miss Graham, delivered with all the impetuosity of her sex, was all that could be desired-and more too. She had assisted in feeding the hungry mob at the Warsaw House as they came straggling in from Carthage, and she should remember where every man sat, and what he said, and how he said it. Unfortunately, she remembered too much.”

Returning to the trial, the defense next had their turn. Near the end of their sixteen witnesses, the defense called on Eliza Graham’s aunt, Ann Fleming. Ann testified she had remembered a large group of men coming for dinner late on the night of the murders but none had mentioned the killing of the Smiths. Although she was in the back kitchen cooking, Ann testified she specifically did not see Sharp or Grover at her business that night. It was said that because Ann viewed the accused, as well as their friends and neighbors, as valuable customers whom she didn’t want to offend, she blatantly contradicted the testimony of her niece Eliza Graham.

On Friday, May 30, 1845, after six days of testimony, the court broke for lunch and the jury met to deliberate and decide their verdict. At 2pm that day the jury returned with a “Not Guilty” verdict. Very few were surprised. The Mormons had already figured they would never see a conviction in Carthage. The Nauvoo Neighbor newspaper did not even mention the trial. A second trial, one for the murder of Hyrum Smith, was never held because the prosecution failed to appear. When it was all over there were two murdered men, five known ringleaders, and no convictions.

In the public’s mind, at least for some, these acquittals exonerated those that stood trial for the crime. It allowed the five who stood trial not only to fit back into society free of any stigma and allowed them to excel in their professions, including being leaders in government. In the same article noted above, John Hay summarized that “there was not a man on the jury, in the court, in the county, that did not know the defendants had not done the murder. But it was not proven, and the verdict of NOT GUILTY was right in the law.” Sometime later, Thomas Sharp was asked if he had murdered Joseph Smith and he simply replied, “Well, the jury said not.”

Moving to Utah

Shortly after the trial, Eliza became a plural wife of John Pack, an illustrious pioneer and famous Mormon settler. While walking across the plains from Nauvoo to Salt Lake City, John Pack felt his wives’ dresses were too long and kicked up too much dust. Pack demanded that his wives cut their dresses so they would not kick up so much dust. Eliza refused. Angered, Pack took Eliza over his knee like a child and cut her dress shorter. When they arrived in Utah, she obtained a divorce.

Once settled in Utah, John Pack helped found the University of Utah. At the “This is the Place” monument outside of Salt Lake City, Utah, a cabin with some of John Pack’s items on display still stands.

After her divorce, Eliza then married Robert Porter and had five children. For a time they settled in Salt Lake. Feelings over the conflicting testimony at the trial in Carthage must have healed because the Flemings sold the Warsaw House and decided to move to California as part of the Gold Rush of 1849. During their move West, the Flemings went out of their way to pay a visit Eliza in Salt Lake City. Although Ann Fleming was partly responsible for the mob leader’s acquittal, she was treated respectfully and cordially on her visit to Utah.

Eliza and Robert eventually moved to Wyoming. They settled on a ranch about eighteen miles south of Evanston near Hillyard on the Bear River. Sadly, Eliza died during the childbirth of her daughter Sady. At the time of this birth, a group of Indians had trapped the family in their home. Because they feared these Indians, Eliza’s family was forced to bury her in an unmarked grave near their home.

Lessons Learned

Eliza Jane Graham stands as a hero in church history. She stood by her story of what she saw and heard in the most intimidating courtroom setting imaginable. And although she risked potential physical harm for showing up at the trial in Carthage, and suffered her courtroom testimony being belittled and discredited, and not believed, Eliza stood true. Perhaps more importantly, Eliza stayed true to her larger convictions of the truth of the restored Gospel. She died a faithful member of the church and her posterity has been blessed by her example and testimony.” Brian Stutzman