The ancient Adena and Hopewell cultures created pipes in the images that they saw and experienced. Ancient cultures respected all that the Great Spirit created, animals, birds, people, and nature. The Adena culture represents the same time frame as the Jaredites (1500 BC – 200 AD) and the Hopewell culture (200 BC – 400 AD) parallels the time frame of the Nephites.

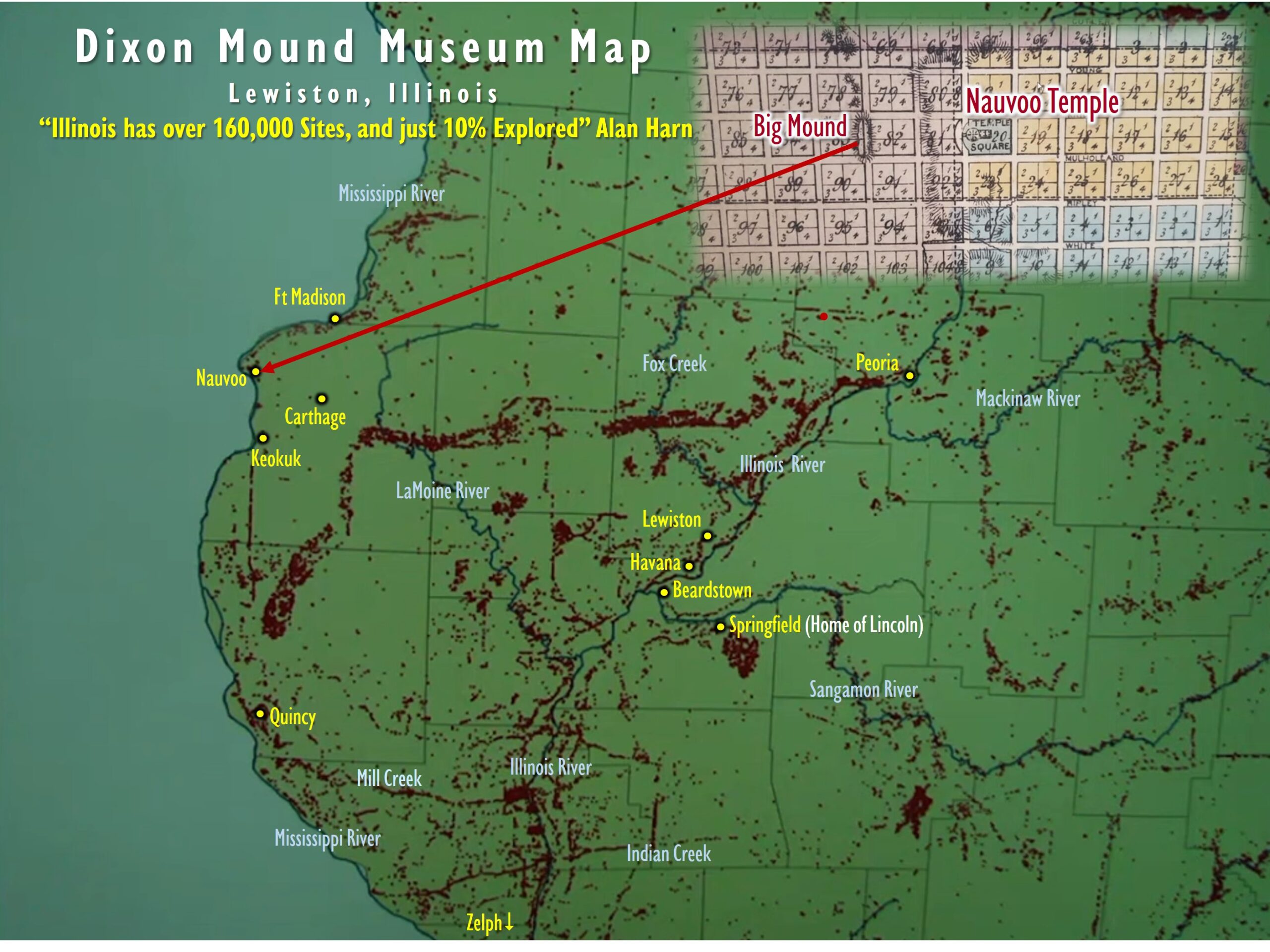

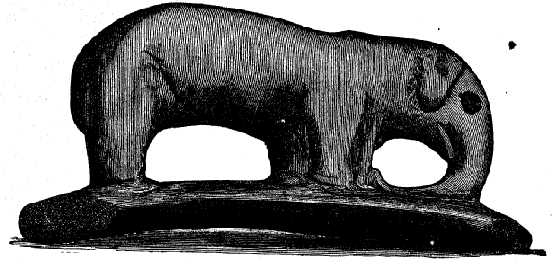

You will read about all the various birds, animals and mammals that the Hopewell spoke about in their effigy design. The Hopewell would obviously create pipes about those things that lived around them including the horse, mammoth, elephant, bison, etc, Most all of these are animals found in North America and mentioned in the Book of Mormon. Another evidence of North America being the land of the Nephites.

Religious Pipes

“There is a bowl for the tobacco in their pipes in the top, and there is a small hole at one end to breathe in the smoke. The pipe was made by Native Americans living in what is today the US state of Ohio. These Native Americans were small-scale farmers who built large burial and ceremonial mounds. There were over 200 pipes buried in a collection of mounds known as the ‘Mound City Group’. The pipe was not simply smoked for pleasure but probably had a religious function. A shaman may have smoked it to evoke the otter as a representative of his clan, or as a spirit guide who would then accompany the shaman on a spiritual journey. Tobacco has been smoked in North America for at least 2300 years and pipe smoking still remains an integral part of modern Native American culture. Tobacco was first brought to Europe in the early 1500s, where it quickly spread across Europe, Africa and Asia.” A History of the World BBC

“On the authority of some older inhabitants of Onondaga, it is stated that on a ledge of rocks, about a mile south of Jamesville, (Near Syracuse and Oneida Castle) is a place which used to be pointed out by the Indians as a spot where the Great Spirit once came down and sat and gave good advice to the chiefs of Onondagas. That there are the prints of his hands and his feet, left in the rocks, still to be seen. In the former years the Onondagas used annually to offer, at this place, tobacco and pipes, and to burn tobacco and herbs as a sacrifice to the Great Spirit, to conciliate his favor and which was a means of preventing diseases.” Author L. Taylor Hansen He Walked the Americas

“Native accounts tell of his arrival [Christ] from the direction of the rising sun, after which he set up his priesthood among his followers known as the “Wau-pa-nu” (the spelling phonetic). They were said to have healed the sick and instituted new laws. Blood sacrifice was forbidden and replaced by the use of tobacco, today an important element in all traditional Native American ceremonies. Among many eastern tribes, East Star Man is regarded as the son of Great Spirit, the Creator.” Wayne May, Christ in North America.

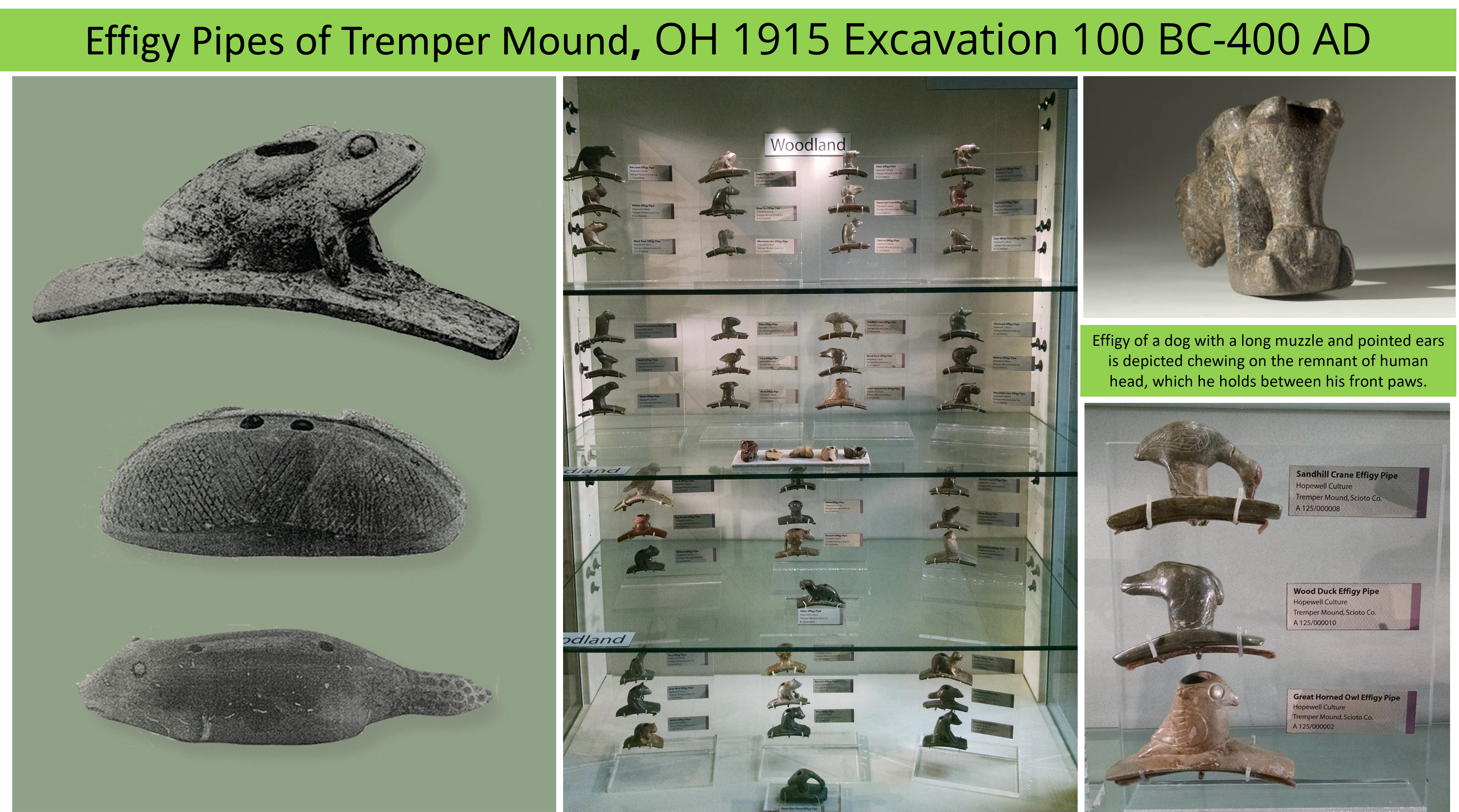

Woodland Animal Effigy Pipes

“During the Woodland period, artisans crafted many ceremonial pipes into the shapes of various animals and sometimes people. The remarkable animal effigy platform pipes of the Hopewell culture are among the most delicate and naturalistic of these sculpted effigies. Archaeologists have found them mainly in ceremonial deposits at two sites, Mound City and Tremper Mound.

The examples shown in the image include an owl, a toad, and a raccoon. The animals may represent the spirit guides of shamans who smoked the pipes to induce a trance state to assist with rituals of healing. Notice how the animal generally would be facing the shaman as he or she smoked the pipe.

It used to be thought that the Ohio effigy pipes had been made from Ohio pipestone, which occurs in Scioto County just across the river from Tremper Mound. Chemical studies of the Tremper Mound pipes, however, have shown that most of these are made from a pipestone found Illinois.” http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Woodland_Animal_Effigy_Pipes

Smoking Pipes and Tobacco

“The earliest archaeobotanical evidence of the use of tobacco in eastern North America comes from the central Mississippi Valley between AD 100 and 200 (uncalibrated RCYBP) (Asch 1991, 1994; Haberman 1984; Wagner 2000; Winter 2000), with dates for the rest of eastern North America falling several centuries later (Haberman 1984; Wagner 2000). These dates indicate that tobacco was a major intoxicant from the Early Woodland onward. However, ethnohistoric accounts indicate that a variety of plants were smoked in addition to tobacco, including Cornus sp. (Dogwood), Juniperus species (Juniper), Rhus glabra (Sumac), and Arctostaphylus uva-ursi (Bearberry) (Brown 1989; Hall 1977; Springer 1981; Yarnell 1964).

Although there remains much to be learned about the evolution of smoke plant use, what can be said is that smoking pipes were the primary means of intoxicant ingestion in prehistoric eastern North America…

The Early Woodland Period and Adena (ca. 1000 BC–AD 200)

Tubular smoking pipes’ are widely known as characteristic Early Woodland period artifacts (Rafferty 2002, 2006, 2008; Rafferty et al. 2012; Salkin 1986). The typical morphology is that of a 1–2 cm wide cylinder with a wide hole at one end and a

narrower opening at the other. The narrow opening could be blocked with a pebble to prevent inhalation of tobacco (Gehlbach 1982; Meuser 1952; Stephens 1957) (Fig. 2.1). Earlier shapes of pipes are more conical in form. Alongside “plain” tubes, we also see during this early period tubes with beveled ends, compound forms with right angle bore extensions, as well as the early forms of platform and elbow pipes, though these are minority types. Pipes at this period are made from several different materials, including clay or soft stone, but iconic specimens are made of a soft limestone from the central Ohio River Valley (Stewart 1989; Thomas 1971, p. 77). These earliest pipes tend to be interred in burials, and often show signs of intentional destruction. Webb and Snow (1974, p. 86) suggested that not all “pipes” were used for smoking, and that some may have been sucking or pigment tubes for shamanic rituals (Frison and Van Norman 1993; Howes 1942). At least one researcher has even proposed that pipes may have served as primitive telescopes (Schoolcraft 1845), though this seems unlikely. I do not dispute the fact that some Early Woodland tubes may have had other uses besides smoking, but specimens in museum collections have sooting and sometimes carbonized residues, indicating a smoking function (Jordan 1959). As discussed in other published papers, there is chemical evidence that further supports a smoking function for early tube pipes (Rafferty 2002, 2006; Rafferty et al. 2012). Residues from five tubular pipes dating to between 500 and 300 BC have been analyzed by the author; three showed clear mass spectra for nicotine or related metabolites…

While early pipes have often been associated with Adena mound builder sites of the Ohio Valley and their local contemporaries (Bense 1994, p. 129), smoking pipes predate the Early Woodland (pre-ca. 1000 BC) and were more widely distributed geographically. Pipes have been recovered from Late Archaic Period (ca. 4000– 1000 BC) burials as well, indicating that smoking’s connection with burial rituals had an earlier origin than has been hypothesized for the entirety of Early Woodland mortuary practices (Concannon 1993, p. 74; Custer 1987, p. 42; Dragoo 1963, p. 241, 1976; Walthall 1980, p. 77). One of the earliest pipes documented in eastern North America was recovered from the Eva Site in Tennessee and dates to ca. 2000 BC (Lewis and Kneberg Lewis 1961, p. 66). Webb and Baby (1957, p. 22) reference tubular pipes from Late Archaic shell mounds in Alabama and Kentucky, which were also, at least in part, functioning as burial contexts (Claassen 1991, 1996). These early examples suggest that the ritualistic function of pipes has a long history in eastern North America…

I have attempted to briefly summarize the history of smoking pipes in the eastern half of North America from their earliest evidence to the eve of European contact. This is the merest scratch on a vast surface. Even so, several trends are clear. Smoking pipes were used quite early in the East, though not so early as in western regions of North America. As early as they were adopted, they became important artifacts for a range of significant social practices, including burial rituals and intersocietal trade and exchange. The earliest pipes were made of stone, and tended towards tubular or platform types, while late prehistory was dominated by numerous plain clay pipes with occasionally more elaborate, often effigy, specimens as well. Tobacco smoking likely began as a specialized practice associated with ritual practices, but over time became more ubiquitous and widespread. Smoking pipes remain socially significant artifacts to Native American traditional cultures to the present day. As always, more research is necessary into the earliest origins, chronological development, and cultural significance of smoking pipes from across the

Ohio History Central

Ohio History Central is an evolving, dynamic online encyclopedia that includes information about Ohio’s natural history, prehistory, and history. Ohio History Central is perfect for anyone wanting to learn more about Ohio! Ohio History Central was researched and written by staff at the Ohio History Connection. Pictures and descriptions below are from Ohio History Connection.

Ohio History Central is an evolving, dynamic online encyclopedia that includes information about Ohio’s natural history, prehistory, and history. Ohio History Central is perfect for anyone wanting to learn more about Ohio! Ohio History Central was researched and written by staff at the Ohio History Connection. Pictures and descriptions below are from Ohio History Connection.

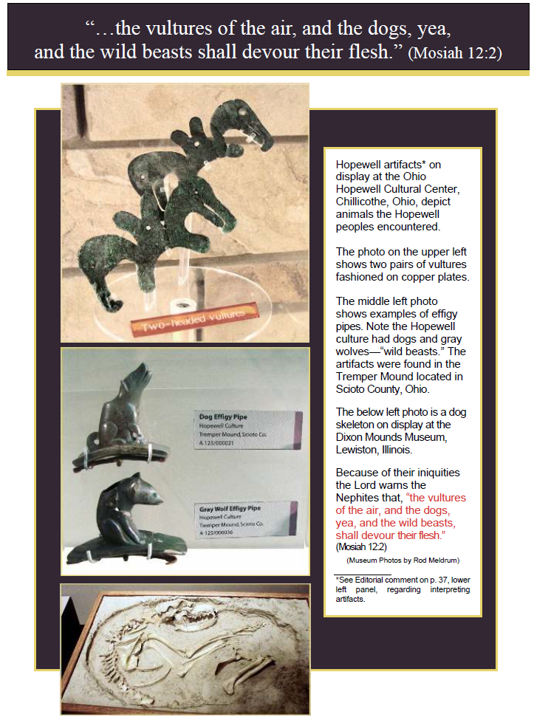

Effigy of a Dog

Description: Effigy of a dog with a long muzzle and pointed ears is depicted chewing on the remnant of human head, which he holds between his front paws. Paws are very blocky and stylized. Left front leg is broken, missing and restored. Part of right rear leg is broken and missing. Tail is tightly curved over the back and attached, forming a ring. Pipe bowl is a roughly rectangular projection in the middle of the dog’s back. Hole for pipe stem is in the dog’s posterior. Stylized human head is upside down. The nose is high relief. The lower jaw is missing. Dog is chewing on occipital region of the head. The artistic style is typical of the Copena Culture from Tennessee region. The effigy is made of dark grayish-brown steatite. Item was excavated from Seip Mound in Paxton Township, Ross County, Ohio.

Description: Effigy of a dog with a long muzzle and pointed ears is depicted chewing on the remnant of human head, which he holds between his front paws. Paws are very blocky and stylized. Left front leg is broken, missing and restored. Part of right rear leg is broken and missing. Tail is tightly curved over the back and attached, forming a ring. Pipe bowl is a roughly rectangular projection in the middle of the dog’s back. Hole for pipe stem is in the dog’s posterior. Stylized human head is upside down. The nose is high relief. The lower jaw is missing. Dog is chewing on occipital region of the head. The artistic style is typical of the Copena Culture from Tennessee region. The effigy is made of dark grayish-brown steatite. Item was excavated from Seip Mound in Paxton Township, Ross County, Ohio.

Description: Large effigy pipe is in the shape of a male dog. It is made of steatite or granite that is mottled very dark grayish-brown and dark gray. The dog’s face has two deep eye sockets and a mouth with indication of teeth carved in the stone. There is a 7-mm hole drilled in the chin. Triangular ears fall forward. The tail curves up over the body and meets the pipe bowl. There is an oval-shaped space carved out between the tail and the body of the dog. The front legs are thinner (24 mm in diameter) than back legs (40.5 mm in diameter) and show distinctive joints. There are holes drilled from front to back in both front legs near the ends. Large chunks are missing from the back legs. There is a hole measuring 21.3 mm at the base of the tail that slopes upward toward the opening of the pipe bowl. Item was excavated from Seip Mound in Paxton Township, Ross County, Ohio.

Description: Large effigy pipe is in the shape of a male dog. It is made of steatite or granite that is mottled very dark grayish-brown and dark gray. The dog’s face has two deep eye sockets and a mouth with indication of teeth carved in the stone. There is a 7-mm hole drilled in the chin. Triangular ears fall forward. The tail curves up over the body and meets the pipe bowl. There is an oval-shaped space carved out between the tail and the body of the dog. The front legs are thinner (24 mm in diameter) than back legs (40.5 mm in diameter) and show distinctive joints. There are holes drilled from front to back in both front legs near the ends. Large chunks are missing from the back legs. There is a hole measuring 21.3 mm at the base of the tail that slopes upward toward the opening of the pipe bowl. Item was excavated from Seip Mound in Paxton Township, Ross County, Ohio.

Description: Front view of an effigy pipe in the form of a dog eating a human head that is grasped between its front paws. The pipe was created by the prehistoric Hopewell people during the Middle Woodland period. It was excavated from Seip Mound in Ross County, Ohio, and is part of the Archeology collections of the Ohio Historical Society.”

As we stated before, It seems the ancient Adena and Hopewell Cultures created pipes in the images in nature that they saw and experienced. Ancient cultures respected all that the Great Spirit created, animals, birds, people, and nature. In the Book of Mormon there are some amazing verses that indicate why the Native Americans may for example created pipes after the image of dogs eating humans.

Alma 16: 9-11 81-77 BC

“And thus ended the eleventh year of the judges, the Lamanites having been driven out of the land, and the people of Ammonihah were destroyed; yea, every living soul of the Ammonihahites was destroyed, and also their great city, which they said God could not destroy, because of its greatness. But behold, in one day it was left desolate; and the carcasses were mangled by dogs and wild beasts of the wilderness. Nevertheless, after many days their dead bodies were heaped up upon the face of the earth, and they were covered with a shallow covering. And now so great was the scent thereof that the people did not go in to possess the land of Ammonihah for many years. And it was called Desolation of Nehors; for they were of the profession of Nehor, who were slain; and their lands remained desolate.”

Mosiah 12:1-3 148 BC

“And it came to pass that after the space of two years that Abinadi came among them in disguise, that they knew him not, and began to prophesy among them, saying: Thus has the Lord commanded me, saying—Abinadi, go and prophesy unto this my people, for they have hardened their hearts against my words; they have repented not of their evil doings; therefore, I will visit them in my anger, yea, in my fierce anger will I visit them in their iniquities and abominations. Yea, wo be unto this generation! And the Lord said unto me: Stretch forth thy hand and prophesy, saying: Thus saith the Lord, it shall come to pass that this generation, because of their iniquities, shall be brought into bondage, and shall be smitten on the cheek; yea, and shall be driven by men, and shall be slain; and the vultures of the air, and the dogs, yea, and the wild beasts, shall devour their flesh. And it shall come to pass that the life of king Noah shall be valued even as a garment in a hot furnace; for he shall know that I am the Lord.”

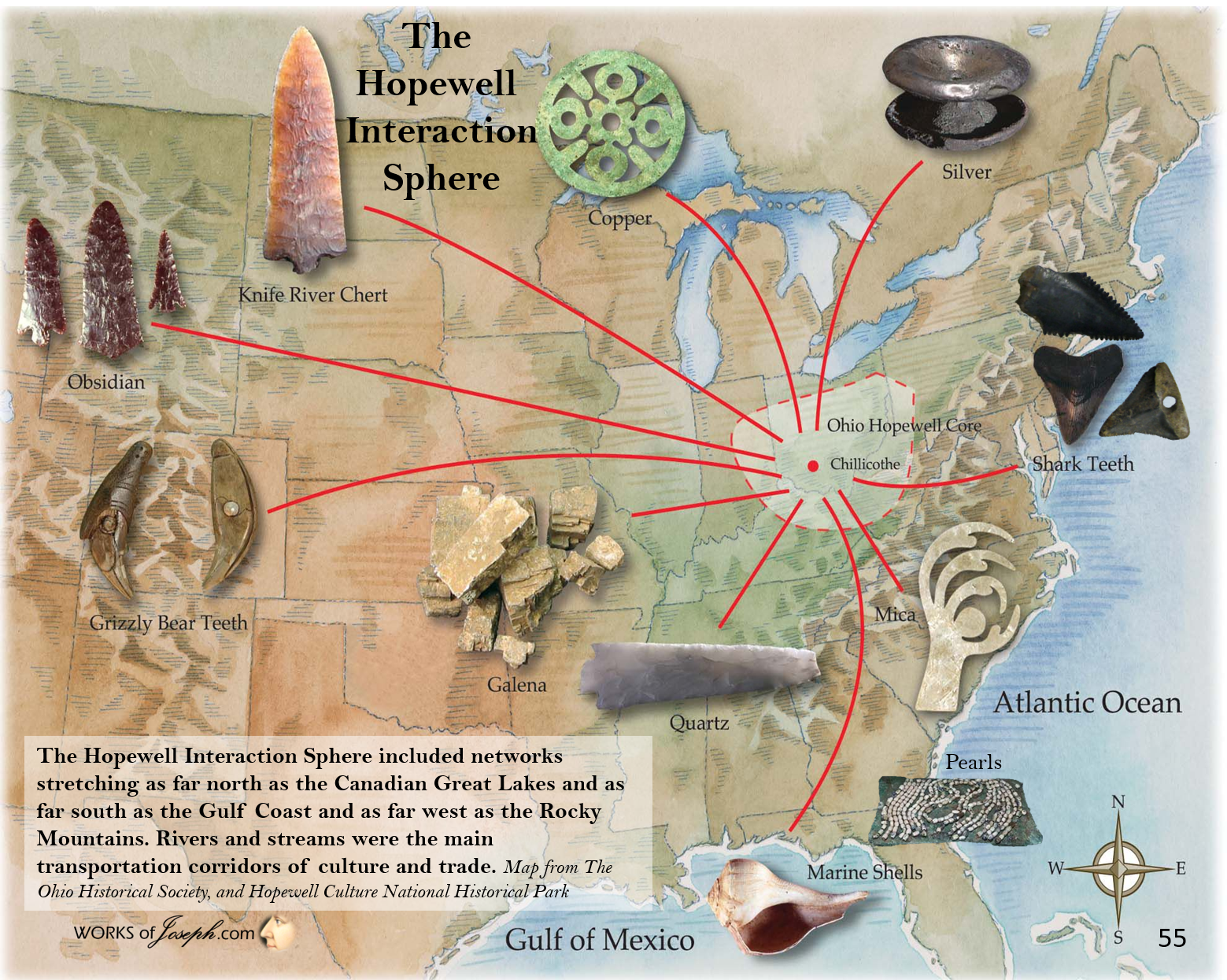

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a dog was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. The dog is seated with its head pointed upward and mouth partially open. A narrow section of bowl (from top edge nearly to the bottom of bowl just behind dog’s left shoulder) and the left forepaw have been restored. The effigy pipe measures approximately 1.5″ x 3.5″ x 1.25″ (3.81 x 8.89 x 3.18 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including dogs, owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. (See map below on how the Hopewell had trade routes to bring mica, pearls, and volcanic rock into their area.) In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a dog was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. The dog is seated with its head pointed upward and mouth partially open. A narrow section of bowl (from top edge nearly to the bottom of bowl just behind dog’s left shoulder) and the left forepaw have been restored. The effigy pipe measures approximately 1.5″ x 3.5″ x 1.25″ (3.81 x 8.89 x 3.18 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including dogs, owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. (See map below on how the Hopewell had trade routes to bring mica, pearls, and volcanic rock into their area.) In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

The Hopewell Interaction Sphere

Description: This is a plaster cast of an effigy pipe known as the Mound City Horned Head. There is a human face with ears on either side. A knob on the forehead and two knobs equidistant on the back of the head represent a headdress. The pipe base is slightly convex in shape. This piece is from Hopewell Culture. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large – the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This is a plaster cast of an effigy pipe known as the Mound City Horned Head. There is a human face with ears on either side. A knob on the forehead and two knobs equidistant on the back of the head represent a headdress. The pipe base is slightly convex in shape. This piece is from Hopewell Culture. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large – the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a gray wolf was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. The animal is seated with all four legs incised in bas relief on bowl; only the front toes are indicated. Its facial features consist of an incised mouth and drilled eyes. The right eye is inset with copper. A section of the upper part of the bowl on the right side and small sections of anterior platform are restored. The effigy pipe measures approximately 1.5″ x 3.5″ x 1.25″ (3.81 x 8.89 x 3.18 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a gray wolf was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. The animal is seated with all four legs incised in bas relief on bowl; only the front toes are indicated. Its facial features consist of an incised mouth and drilled eyes. The right eye is inset with copper. A section of the upper part of the bowl on the right side and small sections of anterior platform are restored. The effigy pipe measures approximately 1.5″ x 3.5″ x 1.25″ (3.81 x 8.89 x 3.18 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a mink was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. The body of the mink winds around the top of the bowl with the animal’s head and tail facing the smoker. Parts of the platform have been restored. Made of dark olive gray stone, the pipe measures approximately .88″ x 1.67″ x 3.75″ (2.2 x 4.1 x 9.5 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a mink was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. The body of the mink winds around the top of the bowl with the animal’s head and tail facing the smoker. Parts of the platform have been restored. Made of dark olive gray stone, the pipe measures approximately .88″ x 1.67″ x 3.75″ (2.2 x 4.1 x 9.5 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of an American crow was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. Effigy consists of the head and neck of the bird. Eyes are drilled. The pipe has been restored. Made of dark gray stone, the pipe measures approximately 1.5″ x 1.5″ x 3.4″ (3.6 x 3.6 x 8.7 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of an American crow was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. Effigy consists of the head and neck of the bird. Eyes are drilled. The pipe has been restored. Made of dark gray stone, the pipe measures approximately 1.5″ x 1.5″ x 3.4″ (3.6 x 3.6 x 8.7 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a raccoon, made of gray and brown mottled pipestone, was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. The animal is shown crouched on bowl of pipe with legs flexed, and its tail extends to the platform. The details of the face–“mask”, mouth, and nostrils–were carefully carved in low relief. The left front leg and adjoining section of bowl, right side of bowl, and right shoulder of effigy are restored, as is the section of the tail that is completely in the round and a small section of the platform. This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 BC-AD 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a raccoon, made of gray and brown mottled pipestone, was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. The animal is shown crouched on bowl of pipe with legs flexed, and its tail extends to the platform. The details of the face–“mask”, mouth, and nostrils–were carefully carved in low relief. The left front leg and adjoining section of bowl, right side of bowl, and right shoulder of effigy are restored, as is the section of the tail that is completely in the round and a small section of the platform. This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 BC-AD 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a porcupine was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. The animal stands with head extended forward and tail extending backward. Some restoration work has been done to the platform. The pipe measures approximately 1.25″ x 1.25″ x 3.75″ (3.1 x 3.1 x 9.5 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a porcupine was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. The animal stands with head extended forward and tail extending backward. Some restoration work has been done to the platform. The pipe measures approximately 1.25″ x 1.25″ x 3.75″ (3.1 x 3.1 x 9.5 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a saw-whet owl was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. The eyes of this owl are set are drilled and set with pearls. Some restoration work has been done to the pipe, which measures approximately 1.15″ x 2″ (2.8 x 4.9 x 7.2 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a saw-whet owl was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. The eyes of this owl are set are drilled and set with pearls. Some restoration work has been done to the pipe, which measures approximately 1.15″ x 2″ (2.8 x 4.9 x 7.2 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a duck was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. Archaeologist William C. Mills identified this as a Buffelhead duck. Made of mottled dark olive gray stone, the pipe measures approximately 1.75″ x 1.5″ x 3.25″ (4.2 x 3.6 x 8.25 cm). Some parts of the pipe have been restored. This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a duck was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. Archaeologist William C. Mills identified this as a Buffelhead duck. Made of mottled dark olive gray stone, the pipe measures approximately 1.75″ x 1.5″ x 3.25″ (4.2 x 3.6 x 8.25 cm). Some parts of the pipe have been restored. This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a mountain lion was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. Mountain lions are also known as pumas, cougars, catamounts, or panthers. The animal stands on platform with its tail extended onto the platform. Mouth is slightly open and ears extend from head. Parts of the pipe have been reconstructed. Made of mottled red and brownish-gray stone, the pipe measures approximately 1.34″ x 1.33″ x 3.6″ (3.3 x 3.25 x 9 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a mountain lion was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. Mountain lions are also known as pumas, cougars, catamounts, or panthers. The animal stands on platform with its tail extended onto the platform. Mouth is slightly open and ears extend from head. Parts of the pipe have been reconstructed. Made of mottled red and brownish-gray stone, the pipe measures approximately 1.34″ x 1.33″ x 3.6″ (3.3 x 3.25 x 9 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a black bear was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. Only the front quarters of the bear are represented. Eyes are drilled and inset with copper. Ears extend from head. Some parts of the pipe have been damaged and other parts have been restored. Made of light olive gray stone, the pipe measures approximately 1.87″ x 1.4″ x 3.33″ (4.8 x 3.6 x 8.5 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a black bear was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. Only the front quarters of the bear are represented. Eyes are drilled and inset with copper. Ears extend from head. Some parts of the pipe have been damaged and other parts have been restored. Made of light olive gray stone, the pipe measures approximately 1.87″ x 1.4″ x 3.33″ (4.8 x 3.6 x 8.5 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River. The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior.

Description: This composite photograph is a front, side and back view of the Adena Pipe. The Adena Pipe is carved out of Ohio pipestone into the likeness of an ancient American Indian man, and was discovered by William C. Mills in 1901 during an excavation of the Adena Mound in Chillicothe, Ohio. Tubular pipes such as this one were common in the Adena culture (800 B.C. – A.D. 1), although effigy pipes are unusual, rendering this particular pipe very unique. As of 2013, it is now recognized as the state artifact of Ohio.

Description: This composite photograph is a front, side and back view of the Adena Pipe. The Adena Pipe is carved out of Ohio pipestone into the likeness of an ancient American Indian man, and was discovered by William C. Mills in 1901 during an excavation of the Adena Mound in Chillicothe, Ohio. Tubular pipes such as this one were common in the Adena culture (800 B.C. – A.D. 1), although effigy pipes are unusual, rendering this particular pipe very unique. As of 2013, it is now recognized as the state artifact of Ohio.

Description: This pipe in effigy (a likeness or representation) of a deer (Or is it?) was excavated from Tremper Mound, a Hopewell culture site located five miles north of Portsmouth in Scioto County. Effigy consists of the upturned head of a deer resting on a platform. The bowl for tobacco is between the ears and eyes. Parts of the platform have been restored. Made of dark gray stone, the pipe measures approximately 1.25″ x 1.25″ x 3.33″ (3.2 x 3.3 x 8.5 cm). This pipe is part of a large collection of pipes found at Tremper Mound. The pipes were carved of Ohio pipestone, a silica-based material that can be easily carved when freshly quarried from the hills east of the Scioto River.

The pipes represent a variety of animals significant to the Hopewell, including owls, wolves, deer and beaver. Skilled Hopewell craftsmen carved the pipes with flint knives and some are embellished with pearls or copper. In Ohio, the Hopewell Indians (100 B.C.-A.D. 500) built burial mounds and large earthen enclosures in geometric shapes (circles, squares, and octagons) to mark the places where the people gathered periodically to participate in many social and ceremonial events. Some of these sites were quite large–the Newark Earthworks complex extends over a 4-square-mile area. The Hopewell people also maintained a large trade network extending as far as the Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, the Florida coast and Appalachians, and northern Lake Superior. View on Ohio Memory.

Is the above picture a Deer or a Horse? The Ohio History Connection lists this as a deer. I agree with Rod Meldrum and think it looks more like a horse.

“And it came to pass that we did find upon the land of promise, as we journeyed in the wilderness, that there were beasts in the forests of every kind, both the cow and the ox, and the ass and the horse, and the goat and the wild goat, and all manner of wild animals, which were for the use of men. And we did find all manner of bore, both of gold, and of silver, and of copper.” 1 Nephi 18:25

For information about horses found in North America see our blog article here:

Native American Tobacco

Tobacco has long played a significant role in the American Indian culture (Paper, 1988; Seig, 1971). Tobacco provides American Indian people a connection between their own culture and the spirit world (Flannery, Sisk-Franco, & Glover, 1995; Hirschfelder & Molin, 1992; Paper, 1988; Winter, 2000). Historically, tobacco was used in medicinal and healing rituals, in ceremonial or religious practices, and as an instructional or educational device. Sacred tobacco was seen as a gift of the earth. It was burned, and the rising smoke was used to cleanse and heal. Often, sacred tobacco was sprinkled around the bed of the ailing individual to protect and to act as a healing agent. Tobacco was also used for social and peaceful purposes to promote well-being and good thoughts (Linton, 1924). Prior to important meetings, sacred tobacco was smoked as a ritualistic exchange and was also used as a powerful teaching tool. Elders, healers, and tribal leaders used tobacco leaves in their storytelling. Symbolically, smoke from sacred tobacco was called “spirits paths” (Linton, 1924, p. 1). It served as a channel to the evil or bad spirits.

Specific rules are to be followed when smoking sacred tobacco, which are just as important as the act of smoking itself. Small puffs of smoke were taken and held in the mouth. Deep inhaling was not encouraged because the smoke was not to be enjoyed but was a symbolic gesture meant to cleanse the air, the heart, and the mind. It became a facilitator to the spirits so that peaceful exchange could be obtained and prayers could be heard (Hodge, 2001).

The Origin of Sacred Traditional Tobacco Kinnikinic

“The key informants on the three Ojibwe reservations talked about the origin of sacred traditional tobacco among their people. Tobacco was described as “one of the first things that the Creator [higher being] gave us to talk to him, was that spirit of tobacco.” All key informants could pinpoint the origin and the actual story of how tobacco came to Anishinabe (Ojibwe) people. However, due to oral tradition, the story or stories could not be told in an interview session like this one and could traditionally be articulated only during approved times of the year. All key informants agreed that a long time ago the original sacred tobacco the Anishinabe used was red willow (kinnikinic). One key informant shared the following:

I know a story that relates to Waynaboozhoo and when in the beginning the Creator told Waynaboozhoo that we wouldn’t be able to communicate directly with the Creator. And so he gave Waynaboozhoo a seed to plant the kinnikinic, which is the red willow. And he said to go and tell the Anishinabe people to plant the seed and that is where they would get the kinnikinic. Then that is the way we would talk to the Creator. That is the way we would communicate with him by smoking our pipes and whatever message we had to convey to the Creator, that the smoke would relay that message. And to put that tobacco, asemaa, on the ground also, near a tree, and this would serve the purpose also of communicating with our Creator.

Also, the Creator said that when we come into this world we have nothing. We come naked and we have nothing to offer. So that is why he gave Waynaboozhoo that seed to give to the Anishinabe people for that offering. Waynaboozhoo refers to the spirit of Anishinabe or original man (Benton-Benai, 1988). To obtain the original sacred tobacco, kinnikinic has to be gathered: “Get the bark off, then shave it down and dry it.” However, when commercial tobacco became available, because it was grown readily, it was easier for many Anishinabe people to just smoke it rather than gather and prepare the kinnikinic. “People just started using it [commercial tobacco] because it was a lot easier.” One key informant added that some quit gathering, preparing, and utilizing the traditional kinnikinic tobacco because “I think they eventually got addicted. So, the nicotine that is in here is the prime reason why they switched over. So that is what I feel like, that eventually this [commercial tobacco] just wiped out the original tobacco.”

Even though Winter (2000) speculated that tobacco may have been the first plant to be domesticated in the New World, one spiritual leader disagrees: I’ve been out in the woods for many years and I have never come across a tobacco plant other than red willow….I never heard my grandparents, they are the ones who raised all of us, ever talk about tobacco like that [commercial tobacco]. But they talked about kinnikinic. They taught us how to make it. I never heard them talk about tobacco or leaves. We never used it [commercial tobacco] or passed it on to the next generation. It is not our way. . . . I think the tobacco that we have nowadays, that started when they did the big tobacco farms. Another added that it seemed “if tobacco was natural, they would be perennials” that would not have to be “replanted every year, because our medicines and sacred plants grow in the bush [the woods] naturally.” There are a few Ojibwe who still harvest kinnikinic.

My husband will gather that kinnikinic for me again this summer. That is what we give to the ceremonies then, when we have ceremonies.” Another said that you will see right here on our reservation “that there is a lot of the elderly people that actually go out and make a daily offering of that original tobacco, kinnikinic. It is still used among the people.” Another key informant added that sacred tobacco “is pretty good tobacco, what the Indians make. They have varieties of tobaccos, too, that they made their own ways.” There are different mixes of sacred tobacco; one said dogwood may also be used. “I used to smoke pipe and my ma used to make a certain type of tobacco. That really smelled good and tasted good. I don’t remember what she used. It was some of the old stuff.” Irwin, Lee & Hirschfelder, Arlene & Molin, Paulette. (1993). The Encyclopedia of Native American Religions: An Introduction. The Western Historical Quarterly.

Natives only had One God

The Hopewell and Adena people had a strong religious affinity. The way they lived may seem unlike what we think of today, but in their own way they believed in “One God” or the “Great Spirit” and He was a central role in their lives. We know the Jaredites lived the gospel in righteousness for many years, as did the Nephites and Lamanites. In Ether 20 we read, “so great was his faith in God, that when God put forth his finger he could not hide it from the sight of the brother of Jared, because of his word which he had spoken unto him, which word he had obtained by faith.”

Ammon converted many of the Lamanites as we read in Alma 19:35-56, “And it came to pass that there were many that did believe in their words; and as many as did believe were baptized; and they became a righteous people, and they did establish a church among them. And thus the work of the Lord did commence among the Lamanites; thus the Lord did begin to pour out his Spirit upon them; and we see that his arm is extended to all people who will repent and believe on his name.”

The Ancient Hopewell and Adena utilized the pipe and tobacco as a way to worship the Great Spirit.

Native Traditions Today

Indian tribes have their own ceremonies. They have their own religions. This was particularly true before the advent of the so-called Christian churches among them. Even today the faithful still cling to their native tradition. Some of them profess Christianity and give token obedience to the so-called Christian churches, but deep in their hearts they still are waiting for the return of the Great White Spirit and the truth.

In many dances, which are largely prayers, significant handclasps are sometimes given. Connected with some of these kiva ceremonies is the wearing of certain types of clothing, and in these clothing are certain marks sacred to the people. I have been told that only the faithful may wear these marks in their clothing, and that only the very good and true may receive these ordinances.

Certain washings and anointing’s are common in many tribes. Usually these are done with water and corn pollen or corn meal, all of which are sacred to the Indian. If it were not for violating confidences I could take you among the Utes and Piutes, and tell of certain “ordinances for the dead.” Among many of the tribes there is a tradition that some day the people will lose their dark color and become white.

Some months ago I spent a few days in the hinterlands of the reservation. Among others that I visited was an old medicine man. His home was so remote that up to this time he had never heard the gospel. As we sat in his home, I began the story of the gospel, using his lovely daughter as an interpreter. As the story progressed, I could see his interest rising, and by the time our story reached the part of the visit of the Savior to this continent and his choosing of the Twelve, he could contain his eagerness no longer.

In his native tongue, for he could speak no English, he said, “I know of that,” and putting up his hands he named the Twelve disciples chosen by the Savior. He gave them all names and in order. As the story continued, more and more he entered into the discussion, supplying parts of it. He was so completely enthralled that he seemed not to notice that we were white people. He fitted in the stories of the people with the message of the restoration.

Later on in the day, as we sat in the shade visiting, I asked him if he would let me have and write the names of the Twelve as he had given them. He thought a while and then cautioned that should I write, I must never give them to the world. They were sacred, and not to be used lightly. But, since I was his friend and knew the story anyway, he would give them to me and I might write them if I would keep them to myself. He then named them one by one, each in its place; there could be no variation.

As we sat there visiting, I thought to try him on another point. “Which of these Twelve are the three that did not die?” I asked. His eyes flashed, he looked at me searchingly. I seemed to read the thoughts in his mind, which were something like this. “How could you white men know about such things?” I said further to him, “Yes, I know about it. It is here in your book, the Book of Mormon. It is no secret. Your forefathers wrote it, and we have it here. I just wanted to see if you could give me the names of the three.”

He sat for some time with his head bowed, and then finally looked up and said, “The names of the Twelve I have just given you, are not the Twelve that he chose on this continent, they are the Twelve that were with him across the waters before he came here. Their names are sacred and must not be used lightly.” After some little time I asked him if he would give me the names of the Twelve chosen here. He looked up at me with a twinkle in his eye and said, “My friend, you have had enough for one time. Come again some other time.” He got up from the log and hurried away and busied himself with some sheep that were in the pen. As I sat there pondering, his wife came over and warned me again of the sacredness of what I had learned and suggested that they should only be used on rare occasions.

On other occasions I have been told the story of the three who never died. Some of the old patriarchs claim that they have seen the three, that they have sat with them in conference and have discussed the program of the Navajo people. But, said one, “They are not just like us although they look like it. They are not dead, but something has happened to their bodies because they can sit with us in council and then, quick as a flash, they are clear across the reservation with another group of Navajos. I do not know how they do it, but I know them and have talked with them many times.” I have scarcely scratched the surface of even the few things that I know, and I am sure that there are countless items of interest and information that have not come to my attention.

It is interesting to note, in closing, that I know of no Indian language in which one can take the name of the Lord in vain. Indeed, I do not know of an Indian language in which they can even swear. They have to learn English or some white man’s language before they can defile the name of Deity.” LAMANITE TRADITION by Golden R. Buchanan PRESIDENT, SOUTHWEST INDIAN MISSION IMPROVEMENT ERA APRIL 1955 See Full Blog Here

Source: https://archive.org/stream/improvementera5804unse/improvementera5804unse_djvu.txt