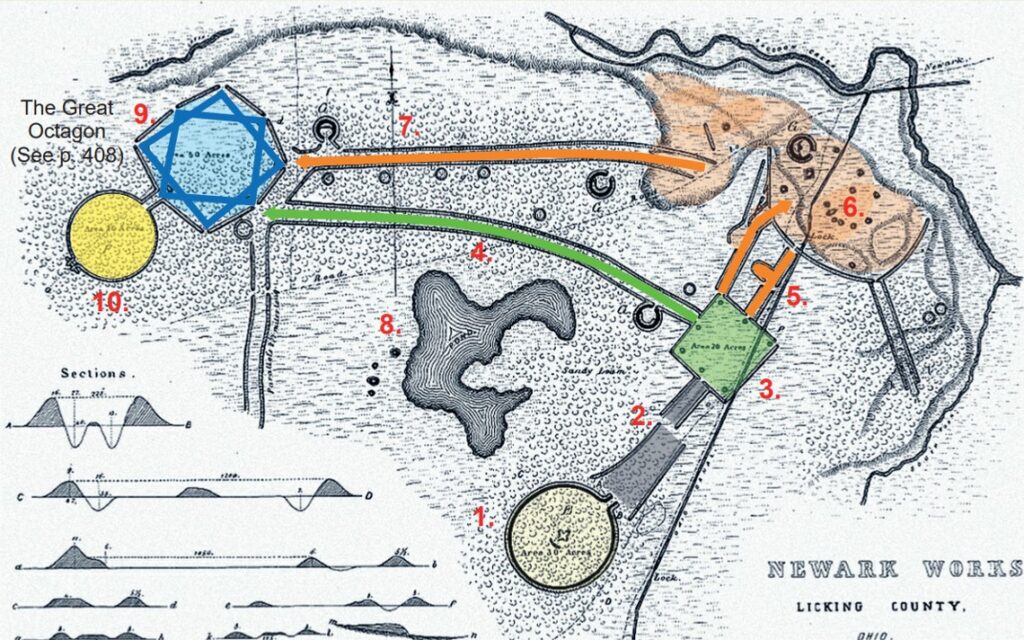

The remains of Ancient civilizations are all around us in the world. We are especially amazed at the importance of civilizations in the Heartland of North America. We have a strong feeling as we search and study the land of Ohio, as the possible location where the Savior appeared after His resurrection to the Nephites. The Newark Earthworks built in 100 BC to 100 AD, has amazing similarities with the Lord’s Plan of Salvation. Near Cincinnati used to be the Hebrew Earthworks, or also called the Menorah Works, until the Army Corp of engineers removed it.

Remnants of Ancient Civilizations in North America

“Mormonism sprang from the mounds,” wrote Roger Kennedy, former director of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

“In the early 1970’s, when they were re-building Joseph’s Red Brick Store, while digging a trench for spot light wiring, they hit some artifacts, which resulted in calling in the archaeologists who then unearthed more artifacts and bones, all carbon dated to the Hopewell civilization of at least 2000 years ago..” Lachlan McKay quoted by Wilson Curlee

“Joseph Smith, his wife Emma, his brother Hyrum and his parents are buried in a Hopewell burial site.” Jonathan Neville

“We learned later that there were ten main mounds that were recognized by the State of Illinois as ancient burials.” Jenny Curlee

“The Mounds, for their part are “steadfast and immovable”, and always greet us with a tender spirit each time we spend time in their presence, which is almost daily from Spring until Fall. To us, and many others, it feels very much like being in the Sacred Grove.” Jenny Curlee

“No other Land fits all the prophecies. And the Book of Mormon happened right here in United States of America. I bear such a powerful testimony of that, and the evidence is all around us.” Jenny Curlee

He [Wayne May] took in everything I told him about the recent information we learned from Lach regarding the burial sites around the Red Brick Store, the tumuli on the old map [Pictured Below] and about us buying some mounds, with enthusiasm. He said, “I’m coming down in a couple of weeks, and we will have some fun!” Jenny Curlee

“In the early 1970’s, when they were re-building Joseph’s Red Brick Store, while digging a trench for spot light wiring, they hit some artifacts, which resulted in calling in the archaeologists who then unearthed more artifacts and bones, all carbon dated to the Hopewell civilization of at least 2000 years ago.” Lachlan Mackay is a member of the Council of Twelve Apostles, for the Community of Christ Church

Blog here called Nauvoo- Sacred Hopewell Mounds

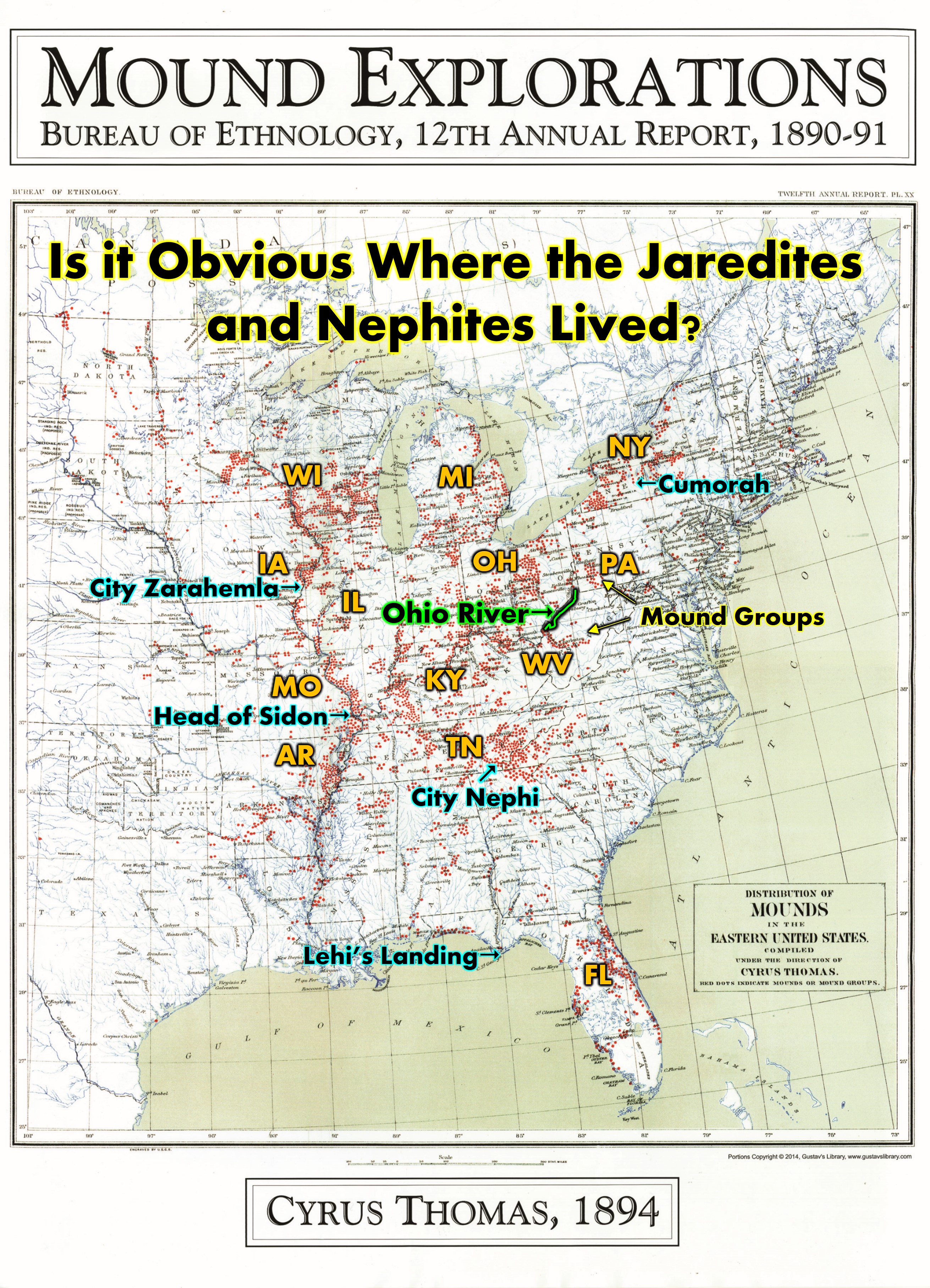

Why Montrose, Iowa?

In our publication called the “Annotated Edition of the Book of Mormon” by David Hocking and Rod Meldrum, they speak to the amazing importance of the City Zarahemla as spoken of in D&C 125. They strongly believe this ancient city was indeed in the United States of America near Nauvoo, Illinois and across the river at Montrose, Iowa.

What are Latter-Day Saints and specifically, FIRM Foundation, The Heartland Research Group, and Ancient American Archaeology, doing to continue the research on this sacred area today?

What about the recent purchase of the replica 600 BC ship called, Phoenicia?

This blog will explore much evidence to the existence of Ancient Civilizations in North America. The Heartland is indeed a special place. Elder Perry said, “The United States is the promised land foretold in the Book of Mormon—a place where divine guidance directed inspired men to create the conditions necessary for the Restoration of the gospel of Jesus Christ.” Elder L. Tom Perry Ensign Dec. 2012

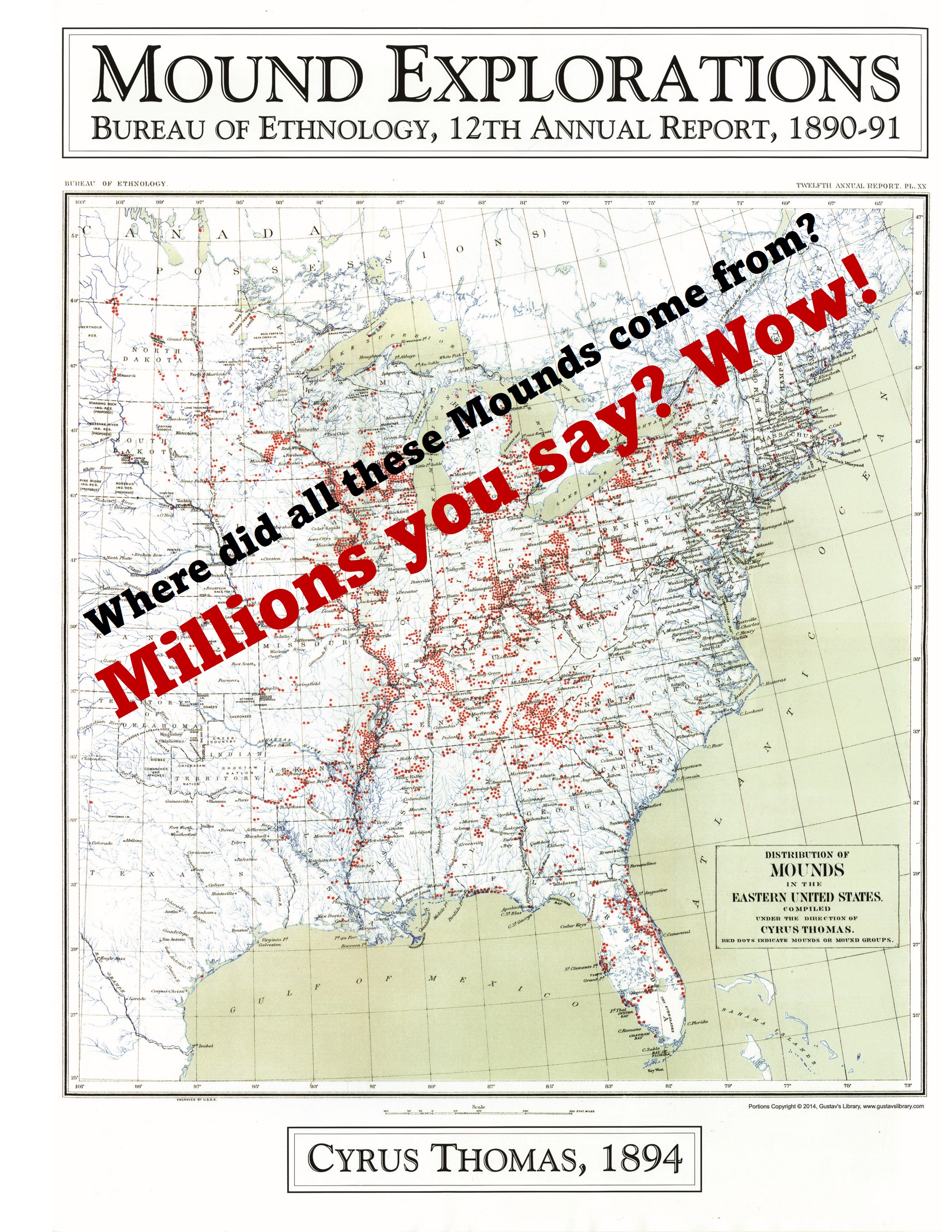

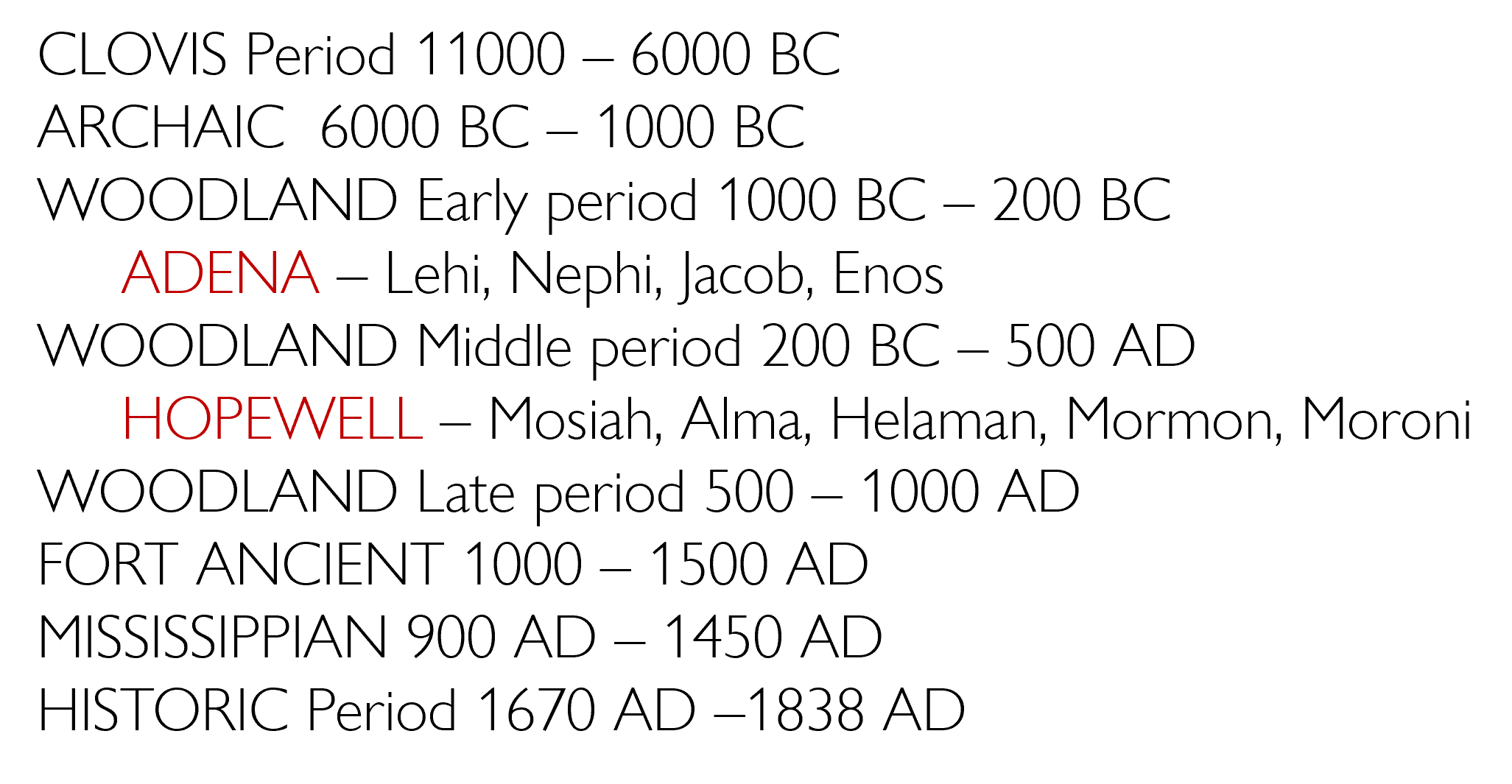

This article below was sent to me by great friends Wes and Ellen Clarke, and I thank them for doing so. It is unbelievable how many artifacts, mounds, copper, burials, and other remains of ancient people in North America are right here in the Heartland where and when the Nephites and Lamanites lived. The Nephite connection to the Hopewell culture and the Jaredite connection to the Adena culture are amazingly compatible.

North American Native Timeline

Remnants of Ancient Civilizations are all Around Us. How Much can we Uncover? By Matt Crossman

Remnants of Ancient Civilizations are all Around Us. How Much can we Uncover? By Matt Crossman

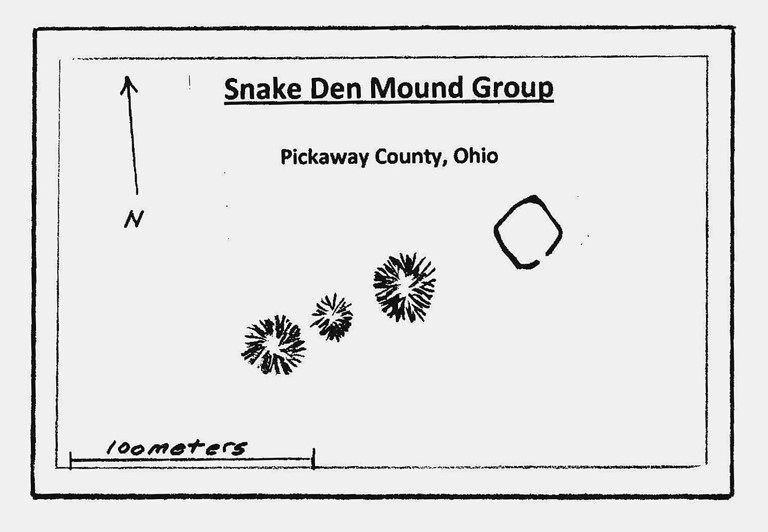

As technology makes it easier to locate Native American ruins, an archaeological site could be in your subdivision. I ride shotgun in a utility vehicle, holding archaeologist Jarrod Burks’s laptop as he drives across a farm in southern Ohio, over the shaved stubble of corn stalks. Back and forth we go at 18 miles per hour, each pass making a T roughly two yards wide and 100 yards long and tall. We’re pulling a trailer with five magnetometers, which measure the Earth’s magnetic field at surface level and below. Burks is using them to look for evidence of ancient Native American activity. I wouldn’t have known that this location, known as Snake Den Mounds, was an archaeological site if Burks hadn’t invited me to meet him there. I wouldn’t have known that the mounds, not much taller than I am, among the trees are 2,000-year-old burial mounds, not natural knolls. And I wouldn’t have known about the mysteries Burks’s magnetometers have found in previous trips to this farm: ancient features called enclosures, which make me think of modern fence lines, except we have no idea what they once enclosed.![]()

After an hour, Burks — director of archaeological geophysics at Ohio Valley Archaeology Inc. and president of Heartland Earthworks Conservancy — climbs out of the vehicle and downloads the magnetometers’ data. On his laptop, we look at a map of the ground we drove over, with dark blotches representing differences in the magnetic field. Blotches forming an obvious shape could mean a discovery, as when Burks found an enclosure shaped like a “squircle”: a square with rounded corners.

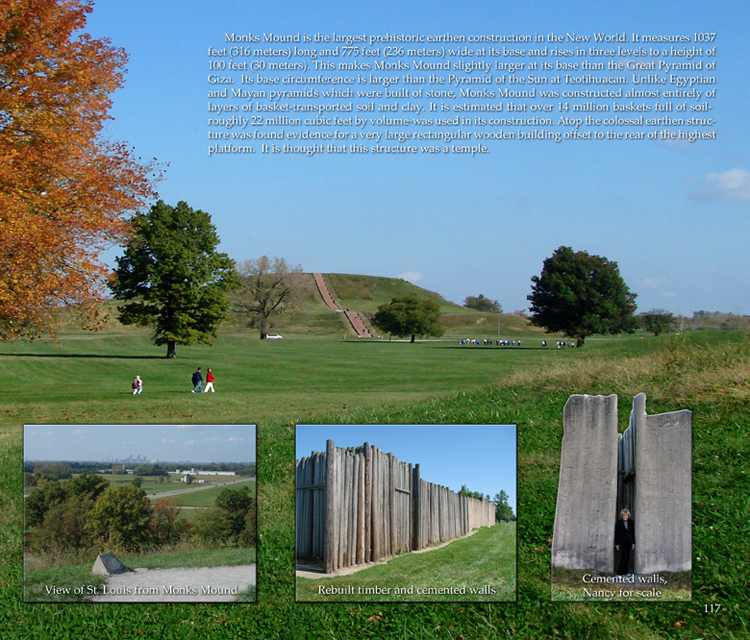

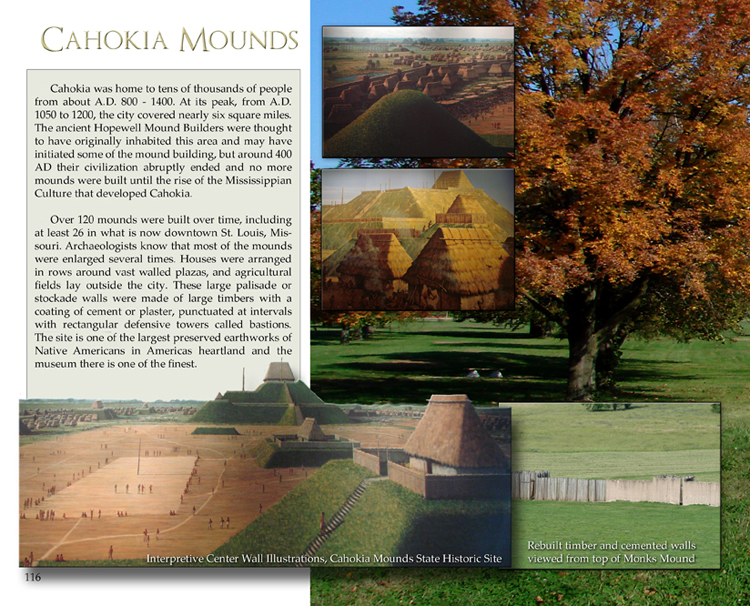

After an hour, Burks — director of archaeological geophysics at Ohio Valley Archaeology Inc. and president of Heartland Earthworks Conservancy — climbs out of the vehicle and downloads the magnetometers’ data. On his laptop, we look at a map of the ground we drove over, with dark blotches representing differences in the magnetic field. Blotches forming an obvious shape could mean a discovery, as when Burks found an enclosure shaped like a “squircle”: a square with rounded corners.  There will be no such discovery today, which is both good news and bad. Archaeologists learn where not to dig by confirming, as we did today, that nothing is there. But they also sometimes realize that something used to be there, but modern development wiped it away. For more than 12,000 years [Editor: I don’t believe their accuracy with this time estimate] before Europeans arrived in North America, Native American cultures dotted what is now the American Midwest. Some subsisted by hunting and moved with the seasons. Some formed complex civilizations whose populations grew to thousands of people. They left behind countless relics, from pottery shards to arrowheads to delicately carved artwork. They left architectural remnants, too, in the form of earthworks like the ones I drove over with Burks, and also mounds shaped like animals, conical mounds and burial mounds. When we think of archaeological sites, we often imagine vast areas cordoned off, like the massive excavations in Rome, or hidden entirely from view, like the Mayan ruins beneath dense forests in Guatemala. But at Snake Den and other places around the world, the evidence of native cultures is sitting in plain sight, in land that has been used and reused so many times that it’s sometimes easier to find evidence of the distant past than the recent one. Finding those sites has become the passionate work of both professional and amateur archaeologists, using technology that has become increasingly accessible. For an archaeologist like Burks, there is always more to discover. “When he stops and yells holy sh—,” says Al Toenetti, a fellow archaeologist who really stopped at the sh sound, “that’s when I know.” But how much access Burks and others will have to those holy sh moments is an open question. Many property owners, wary of the consequences if something is found on their property, are reluctant to let archaeologists on site to look. And so archaeologists face a baffling conundrum: They are more equipped than ever to uncover lost mysteries and frustratingly unable to do so. As we find more archaeological treasures from the past world, we’re more likely to find them bumping into the present. This issue is becoming more pressing, in part because of advances in technology over the past 20 years. Instead of sifting through mounds of dirt, archaeologists now do the same with data, which is collected via ground-penetrating radar, photogrammetry, magnetometry, and a laser technology called lidar. Matt Woodlief, a lecturer at Northeastern University who teaches an Intro to Radar and Lidar Remote Sensing class, describes using lidar as sweeping the ground, only with lasers instead of broom bristles that collect data instead of dirt. The millions of data points that come back, each showing the velocity and angle of the laser’s return, can be translated into a 3D map of whatever was swept. That means more potential discovery, with far less effort. It also means more opportunities for what Burks calls “earthwork fever” — an obsession that non-archaeologists get after they visit earthwork sites. A friend of his spends many lunch hours poring over Google Earth photos, looking for unmapped sites. I don’t have it quite that bad (yet), but I came down with mild symptoms after taking my wife and kids to Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, probably the most important mound site in the United States. Covering 3.5 square miles, Cahokia sits across the Mississippi River from St. Louis in southwestern Illinois. It comprises 51 platform, ridgetop and conical mounds, including Monks Mound, a four-tiered structure, 98 feet tall — the largest earthen structure in the country. [Editors’ Note: Cahokia is dated at about 1000 to 1200 AD long past the dates for it to be a Nephite Mound, but there are many mounds in the 500 BC to 400 AD range all over North America] The Grand Plaza, a 40-acre square plot, sits just south of Monks Mound. It was used, in part, as a sports field. The people who lived there played a game called chunkey, which was something like skeet shooting, except not in the air: someone rolled a stone on the ground, and competitors threw their spears at it. At its peak, from A.D. 1050 to 1200, Cahokia was the biggest city north of Mexico. Estimates put the population as high as 20,000 — more than London at the time. Counting the surrounding area, it might have been more than double that. I live in the St. Louis suburbs; there were suburban dads here more than 1,000 years before me.

There will be no such discovery today, which is both good news and bad. Archaeologists learn where not to dig by confirming, as we did today, that nothing is there. But they also sometimes realize that something used to be there, but modern development wiped it away. For more than 12,000 years [Editor: I don’t believe their accuracy with this time estimate] before Europeans arrived in North America, Native American cultures dotted what is now the American Midwest. Some subsisted by hunting and moved with the seasons. Some formed complex civilizations whose populations grew to thousands of people. They left behind countless relics, from pottery shards to arrowheads to delicately carved artwork. They left architectural remnants, too, in the form of earthworks like the ones I drove over with Burks, and also mounds shaped like animals, conical mounds and burial mounds. When we think of archaeological sites, we often imagine vast areas cordoned off, like the massive excavations in Rome, or hidden entirely from view, like the Mayan ruins beneath dense forests in Guatemala. But at Snake Den and other places around the world, the evidence of native cultures is sitting in plain sight, in land that has been used and reused so many times that it’s sometimes easier to find evidence of the distant past than the recent one. Finding those sites has become the passionate work of both professional and amateur archaeologists, using technology that has become increasingly accessible. For an archaeologist like Burks, there is always more to discover. “When he stops and yells holy sh—,” says Al Toenetti, a fellow archaeologist who really stopped at the sh sound, “that’s when I know.” But how much access Burks and others will have to those holy sh moments is an open question. Many property owners, wary of the consequences if something is found on their property, are reluctant to let archaeologists on site to look. And so archaeologists face a baffling conundrum: They are more equipped than ever to uncover lost mysteries and frustratingly unable to do so. As we find more archaeological treasures from the past world, we’re more likely to find them bumping into the present. This issue is becoming more pressing, in part because of advances in technology over the past 20 years. Instead of sifting through mounds of dirt, archaeologists now do the same with data, which is collected via ground-penetrating radar, photogrammetry, magnetometry, and a laser technology called lidar. Matt Woodlief, a lecturer at Northeastern University who teaches an Intro to Radar and Lidar Remote Sensing class, describes using lidar as sweeping the ground, only with lasers instead of broom bristles that collect data instead of dirt. The millions of data points that come back, each showing the velocity and angle of the laser’s return, can be translated into a 3D map of whatever was swept. That means more potential discovery, with far less effort. It also means more opportunities for what Burks calls “earthwork fever” — an obsession that non-archaeologists get after they visit earthwork sites. A friend of his spends many lunch hours poring over Google Earth photos, looking for unmapped sites. I don’t have it quite that bad (yet), but I came down with mild symptoms after taking my wife and kids to Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, probably the most important mound site in the United States. Covering 3.5 square miles, Cahokia sits across the Mississippi River from St. Louis in southwestern Illinois. It comprises 51 platform, ridgetop and conical mounds, including Monks Mound, a four-tiered structure, 98 feet tall — the largest earthen structure in the country. [Editors’ Note: Cahokia is dated at about 1000 to 1200 AD long past the dates for it to be a Nephite Mound, but there are many mounds in the 500 BC to 400 AD range all over North America] The Grand Plaza, a 40-acre square plot, sits just south of Monks Mound. It was used, in part, as a sports field. The people who lived there played a game called chunkey, which was something like skeet shooting, except not in the air: someone rolled a stone on the ground, and competitors threw their spears at it. At its peak, from A.D. 1050 to 1200, Cahokia was the biggest city north of Mexico. Estimates put the population as high as 20,000 — more than London at the time. Counting the surrounding area, it might have been more than double that. I live in the St. Louis suburbs; there were suburban dads here more than 1,000 years before me. “Festivals at Cahokia were mostly centered around group meals where people feasted on barbeques of deer, bison, squirrels, and even swans. Centuries later, archaeologists found huge party trash pits full of fire-cracked bones and broken dishes.” Annalee Newitz, in the 2021 book Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age Farms separated neighborhoods (which is true today, too, at the outer reaches of the suburbs), and mounds became gathering places. Tim Pauketat, an archaeologist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, believes Cahokia was a spiritual center. Cahokians loved a party, according to the 2021 book, Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age, by Annalee Newitz. “Festivals at Cahokia were mostly centered around group meals where people feasted on barbeques of deer, bison, squirrels, and even swans,” Newitz writes. “Centuries later, archaeologists found huge party trash pits full of fire-cracked bones and broken dishes.” In archaeological searches, relics of modern life often mix with artifacts from the ancient. In 2020, a team of researchers from St. Louis University compared the results of lidar and photogrammetry created by drone images at Cahokia. The remote sensing revealed the razed foundations of houses from a 1940s-era subdivision, a centimeter or two tall, hidden by the grass. The team had walked right over that exact spot and seen nothing. Continued below…

“Festivals at Cahokia were mostly centered around group meals where people feasted on barbeques of deer, bison, squirrels, and even swans. Centuries later, archaeologists found huge party trash pits full of fire-cracked bones and broken dishes.” Annalee Newitz, in the 2021 book Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age Farms separated neighborhoods (which is true today, too, at the outer reaches of the suburbs), and mounds became gathering places. Tim Pauketat, an archaeologist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, believes Cahokia was a spiritual center. Cahokians loved a party, according to the 2021 book, Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age, by Annalee Newitz. “Festivals at Cahokia were mostly centered around group meals where people feasted on barbeques of deer, bison, squirrels, and even swans,” Newitz writes. “Centuries later, archaeologists found huge party trash pits full of fire-cracked bones and broken dishes.” In archaeological searches, relics of modern life often mix with artifacts from the ancient. In 2020, a team of researchers from St. Louis University compared the results of lidar and photogrammetry created by drone images at Cahokia. The remote sensing revealed the razed foundations of houses from a 1940s-era subdivision, a centimeter or two tall, hidden by the grass. The team had walked right over that exact spot and seen nothing. Continued below…

The Heartland Reseach group began with Wayne May, John Lefgren, Rod Meldrum and Rian Nelson conducting magnetometry and ground penetration radar 5 years ago in Ohio. See Blog HERE and HERE

That research continues today as we have many discoveries that are helping us, as we try and find any link to the Ancient City or Land of Zarahemla near Nauvoo or Montrose Iowa. With a great workload and many who desire to help, our large Heartland Group has been organized to better focus on specific research and development projects. We now have two specific groups involved in the Nauvoo area. They are:

1- Ancient American Zarahemla Temple Site – Montrose, IA

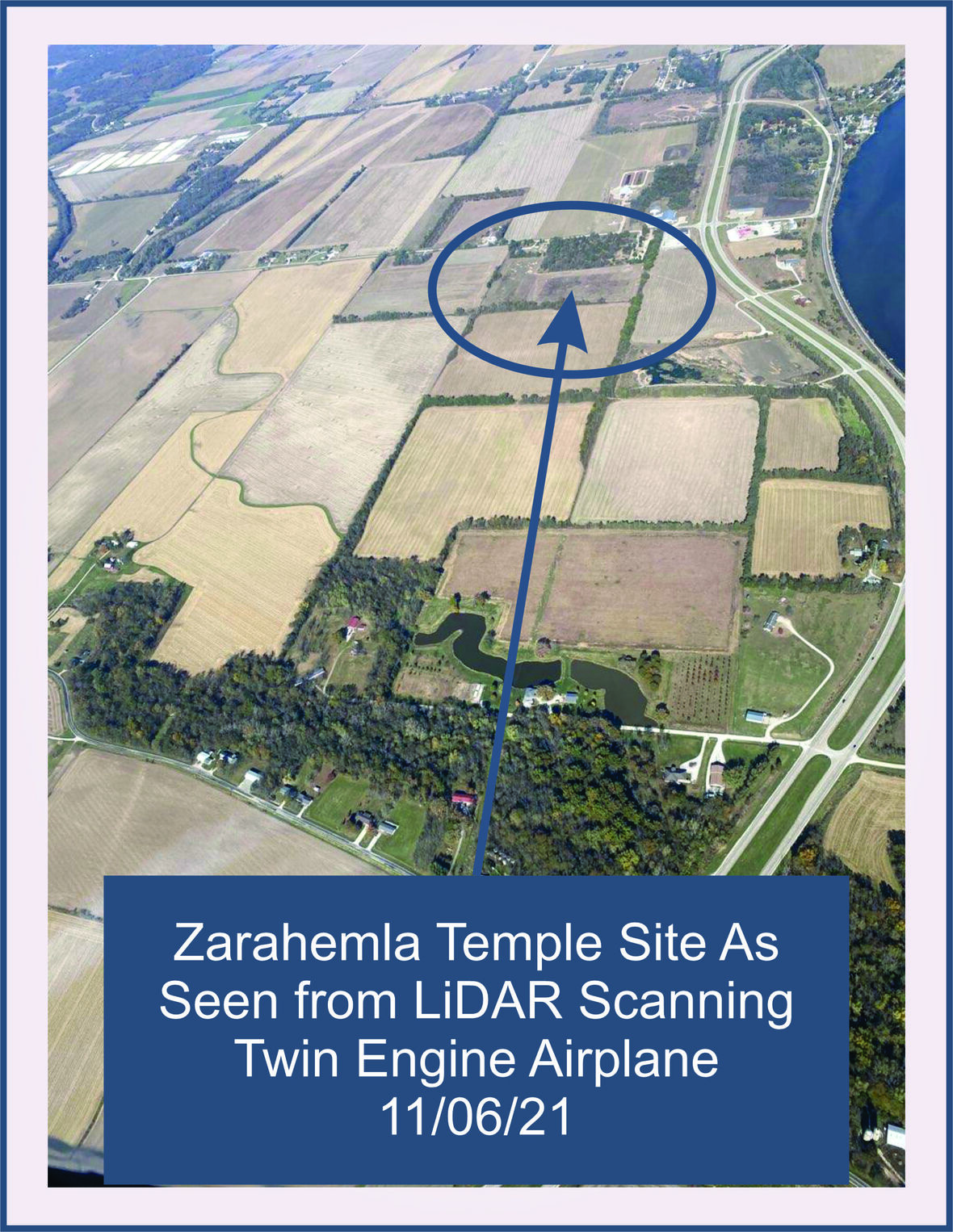

Today, Dr. Kevin Price and Wayne May continue aggressively in work with scientists from Russia, Germany and experts from the United States. They have done extensive LiDAR all over the Iowa and Nauvoo area and are finding incredible information. Blog Here

Donate Here; Ancient American Zarahemla Temple Site – Montrose, IA

Nov. 6th 2021, a historic flyover near Nauvoo, Illinois of 34,000 acres was completed, obtaining Lidar Data to continue searching for more evidence about the Montrose, IA, or the Zarahemla area. In the Nauvoo area Wayne and Kevin are finding ancient fire pits and artifacts, doing additional core hole drilling, magnetometry, lidar, archaeological research, drone exploring, and many other new world scientific studies with experts from all over the world.

Wayne and Kevin are also continuing study of the Michigan plates that Wayne May has been researching over 30 years, and continuing to research information about the Spotted Bee Balm plant which Dr. Kevin Price discovered growing in the Montrose, Iowa area. More here:

Historic Flyover near Nauvoo, Illinois of 34,000 Acres

2- Phoenicia Re-Building and Museum

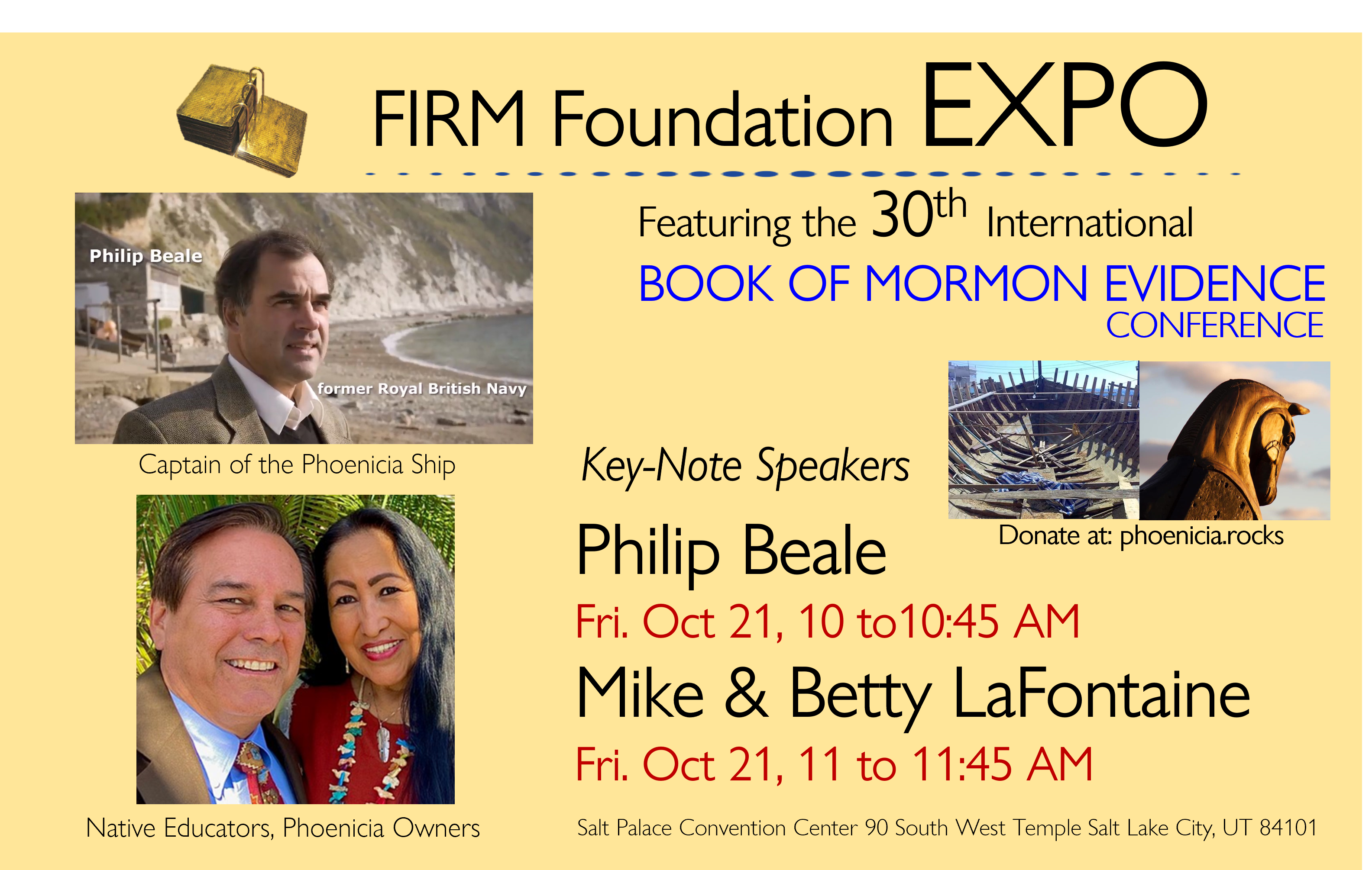

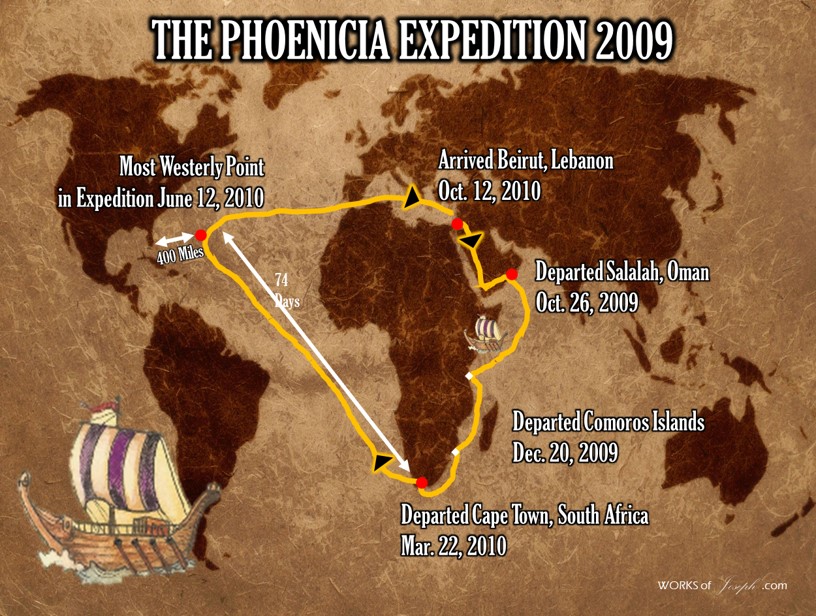

Mike and Betty Lafontaine, with Dr. John Lefgren, have purchased the 600 BC replica Phoenicia Ship in which Captain Philip Beale sailed it in 2009 and again in 2020, over 30,000 miles to prove it was possible for Lehi and Mulek to make their voyage from the Old World to Florida. This ship sits in Montrose Iowa with restoration work any volunteer can help with. We believe this location of Montrose is where the Mulekites ship docked after its journey from Tunisia.

October Expo- Phoenicia Ship Updates

Join us to help rediscover the Land of Zarahemla in the Heartland of the United States. Come to our Oct 20-22, 2022 Expo and meet the Phoenicia Group, Captain Beale from England and see many speakers like Rod Meldrum, and Mike and Betty LaFontaine, who will speak about this newly purchased ship and how you can volunteer to put it back together.

Blog HERE: Donate Here: Phoenicia Rocks Museum

Click for Conference Tickets

Continued from above…”Yes, a subdivision was once built on arguably the pre-eminent archaeological site in the country. So was a drive-in movie theater; it was called Mounds Drive-in and showed X-rated movies in the 1970s. Both were bulldozed in the 1980s. There’s now an effort in Congress to make Cahokia a national park. But while sites like Cahokia are protected, there are many other places where ancient mounds are simply part of the landscape on private land. And as technology has matured, so has our knowledge of where these features exist. In 1914, an atlas catalogued 587 enclosure sites in Ohio, Burks tells me. Now, archaeologists know there are dozens more enclosures in the state, and many more features at other known locations. In 2021, Portland State University researchers Tia Cody and Shelby Anderson created a mound detection predictive model using lidar and aerial imagery and deployed it in Oregon’s forested Willamette Valley. The model successfully identified every previously known mound in the surveyed area, and 44% of the features it tagged as potential mounds were verified as mounds via fieldwork. (Among the unverified mounds were a few pitching mounds on baseball fields.) Many of these discoveries amplify what archaeologists already know, as if a baseball archivist found lost video of Babe Ruth hitting home runs. But some discoveries have been more powerful than that. Consider Burks’ discovery at Fort Ancient, a 3.5-mile-long enclosure on a hilltop in Warren County, Ohio, built by the Hopewell culture around 2,000 years ago. The site has been studied for 150 years. But in 2005, Burks discovered a feature, dubbed Moorehead Circle, where ritual ceremonies had been held. It included three circles of posts, trenches and many burned layers — all of which combined for an enormous holy sh moment. Indeed, the more Burks finds, the more he wonders what he’s missing. He points out a spot in the cornfield at Snake Den where the magnetometer found a long-buried rectangle-shaped enclosure. “You can’t see that rectangle. If there’s that kind of invisible thing at a known site …” his voice trails as he ponders the possibilities. “Ohio’s a big place. How many totally unknown earthworks sites are there in this region? We’ve already shown that there are a lot.” I travel to expose my ignorance to light, and my visits to earthwork sites in Ohio, Missouri, Illinois, and Wisconsin have been blinding. I love to hike deep in the woods, far from everywhere, and imagine nobody has ever stood there. PFFT! I canoed a 50-mile stretch of the Wisconsin River last summer near several mound locations. An archaeologist told me that no matter where I camped on the banks, Native Americans had camped there thousands of years ago, because the Wisconsin River acted as one leg of a watery interstate highway system connecting the Gulf of Mexico with the Atlantic Ocean via the Mississippi River basin and the Great Lakes. At Snake Den — so named because researchers found evidence snakes had made their home in its mounds long after humans abandoned them — the layers of civilization surrounded me. In the distance, 30 miles away, rose the skyline of the city of Columbus. (The irony of encountering that name as I reported on land use in America before European contact didn’t occur to me until later.) Behind me, underground, a line of pits dated to 900 B.C. (according to carbon dating, at least, though Burks wonders if that measurement is accurate). The burial mounds to my left — in which eight bodies and one set of cremated remains were found — were built between 100 B.C. and A.D. 250. The farm under which this all rests originated in about 1820. A gas line from 1930 runs under the property. This little farm in the middle of nowhere Ohio has been used and abandoned who knows how many times, by who knows how many groups, over nearly 3,000 years. John Low, a citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, a professor at Ohio State University and the director of the Newark Earthworks Center in Newark, Ohio, isn’t surprised at that level of turnover. “That’s how history works,” he says. “There’s important stuff built on top of other important stuff.” Continued below...

The Newark Earthworks, built between 100 A.D. to 100 A.D.,* originally encompassed more than four square miles. Taken as a whole, the earthworks appear to symbolize elements of the Plan of Salvation and Redemption:

- Pre-Mortal Life as spirits being born with a…

- Veil of Forgetfulness to begin mortal…

- Earth life: “the four corners of the earth”

- Direct path after death to a higher kingdom

- Spirit Prison (holding area for the wicked)

- Paradise (Gospel preached to the dead)

- Vicarious Path with multiple check points

- Lake of Filthy Water (worldly temptations)

- Terrestrial Kingdom (cf. 1 Cor. 15:40) The Seal of Melchizedek consists of two interlocked (or overlapping) squares, making what appears to be an eight-pointed star within the octagon.

- Celestial Kingdom (narrow path entered only through the realm of the Melchizedek Priesthood)

Continued from above, “Newark Earthworks Center, built by the Hopewell in the first four centuries A.D., once took up four square miles; development has erased much of it. It shares ground today with a golf course. So apparently, we have built less-than-important stuff on top of important stuff. But even that, Low says, is looking at it with a Western point of view. To the people who built these mounds, it’s not the “stuff” that makes a site important, Low says. “Before the mounds and the earthworks were built, the sites were already sacred. They’re not sacred by human intervention, not sacred by human designation,” Low says. “In the Western world, we build a church, or a mosque, or a temple, and we call that sacred until we’re done using it, and then we move on. These earthworks and mounds are built to celebrate the pre-existing sacredness of the site.” The structures that marked those sacred sites are disappearing, destroyed by modern development or plowed under by farmers. Wisconsin once was home to tens of thousands of mounds, an estimated 80 percent of which have been destroyed. Cartographers have mapped earthworks’ locations for more than 100 years, and even locations on those maps are disappearing. “This has occurred too many times across the state. I’ll pull up a surface model from the lidar data and I see nothing,” says Mike Farkas, associate research scientist for archaeological data at the Illinois State Archaeological Survey. “The site and mounds are gone. I mean entirely gone, erased from the landscape. Archaeological sites are being destroyed, and it is just so difficult to get most people to notice or even care. I see it like a page being lost from the book of our history.” Woodlief says lidar and other remote sensing technologies will continue to become cheaper and easier to use, making it easier for professionals and amateurs drawn to these sites to discover what’s there before it gets destroyed. But for private landowners, there are disincentives to investigating their property further. Yet ignoring remote sensing has consequences, too, if you later have to dig on your property and come across an unexpected artifact. “Once you start digging and you hit something, then the whole project stops; it becomes a whole investigation,” says Woodlief, who extracts data from remote sensing technology as an engineer for Esri, a geographic information systems company. And getting access to private sites is already a challenge, even for university researchers. The Portland State study involved the property of 17 owners. Only three granted the researchers permission to be on site. Burks, too, often encounters problems gaining access to private property. That’s one reason he studies Snake Den. Not only do owners Pat and Dean Barr cooperate, they participate. They were there the day I visited and eager to describe their passion for the site. Dean shaved the corn stalks to make driving the utility vehicle easier. Dean, a retired teacher, and Pat, a former elementary school librarian, care deeply about education. They want to turn Snake Den into an educational site students can visit on field trips. Determining who decides which sites get preserved, which are worth preserving, and how to preserve them is an ongoing challenge. We are finding ancient sites all the time, changing old ones, and even creating new ones that will be studied centuries from now. I imagine archaeologists 2,000 years from now unearthing all the places where I’ve lived: the house I lived in after college that was torn down and replaced by another one; the dingy apartment that was converted to a hair salon, and later a pastry shop. I recently moved out of a subdivision called Schrader Farms — the name itself speaks to building important stuff on top of other important stuff. I wonder if my basement will still leak in the 41st century.” Published on July 20, 2022 Matt Crossman is a writer based in St. Louis. He has written for Sporting News, Sports Illustrated, The Athletic, Men’s Health, and The Washington Post.